![]()

The past and future of the West cannot be fully comprehended without appreciation of the twinned relationship it has had with Islam over some fourteen centuries. The same is true of the Islamic world.

CHAPTER 1

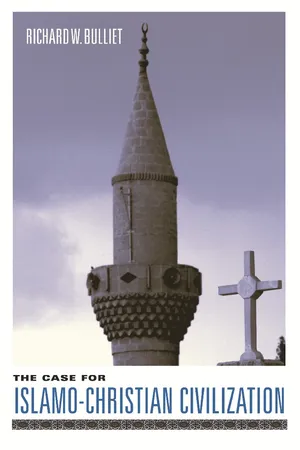

The Case for Islamo-Christian Civilization

AWESOME POWER resides in the terms we employ. Harvard professor Samuel Huntington’s use of the phrase “Clash of Civilizations” as the title of an article in Foreign Affairs in 1993 illustrates this truth. Pundits and scholars immediately sorted themselves out as supporters or critics of Huntington’s phraseology, as often as not basing their opinions more on the rhetoric of the title than on the specifics of his argument. By wielding these three words at a propitious moment, and under respected auspices, Huntington shifted a discourse of Middle East confrontation that had been dominated by nationalist and Cold War rhetoric since the days of Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950s and 1960s. The new formulation took on almost cosmic proportions: the Islamic religion, or more precisely the world Muslim community that professes that religion, versus contemporary Western culture, with its Christian, Jewish, and secular humanist shadings. How quickly and fatefully a well-chosen phrase can challenge perceptions of reality.

In all fairness, it must be recognized that Huntington imputes no particular religious notions to the “Islamic civilization” he sees as fated to confront the West in the twenty-first century. His argument focuses on comparing an idealized “Western civilization,” based on democracy, human rights, free enterprise, and globalization, with economic, social, and political structures in other parts of the world that he sees as unsympathetic, adversarial, and incapable of betterment. This line of thought does not differ greatly from the theories of global progress toward modernity, as exemplified by the contemporary West, that were popular in the quarter century following World War II. However, Huntington’s version corrects a shortcoming of those earlier “modernization” theories. In the 1950s and 1960s theorists commonly opined that modernization would relegate religion to an insignificant role in public affairs. But the surge of Islamic political activism that hit a first crest in the Iranian Revolution of 1979 showed the hollowness of these predictions and thus opened the way for Huntington to reintroduce a religious terminology, albeit one barren of religious elaboration, into a more pessimistic prediction of future developments.

It is hard to strip religious terms of religious content, however. The “Islamic civilization” in Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” has been understood religiously, at least some of the time, by defenders and detractors alike. Coincidentally, the same phrase appeared in a book title in 1926: Young Islam on Trek: A Study in the Clash of Civilizations.1 Its author, Basil Mathews, was Literature Secretary in the World’s Alliance of YMCA’s, but his vision of Islam, similar to many others of the same period, would strike many of Huntington’s admirers as being right up-to-date.

The system [i.e., Islam] is, indeed, in essence military. The creed is a war-cry. The reward of a Paradise of maidens for those who die in battle, and loot for those who live, and the joy of battle and domination thrills the tribal Arab. The discipline of prayer five times a day is a drill. The muezzin cry from the minaret is a bugle-call. The equality of the Brotherhood gives the equality and esprit de corps of the rank and file of the army. The Koran is army orders. It is all clear, decisive, ordained—men fused and welded by the fire and discipline into a single sword of conquest.2

Can we have a liberalized Islam? Can Science and the Koran agree? … Conviction grows that the reconciliation is not possible. Islam really liberalized is simply a non-Christian Unitarianism. It ceases to be essential Islam. It may believe in God; but He is not the Allah of the Koran and Mohammed is not his Prophet; for it cancels the iron system that Mohammed created.3

Huntington’s partisans—except for the evangelical Christians among them—would not see eye to eye with Mathews on everything. As a missionary, Mathews expressed a firm conviction that Protestant Christianity could be what he calls “a Voice that will give [young Muslims] a Master Word for living their personal lives and for building a new order of life for their lands.” His criticism of the West oddly echoes some of the voices of the Muslim revival, suggesting that this sort of criticism can take root in other than Muslim soil:

Western civilization can never lead them to that goal. Obsessed by material wealth, obese with an industrial plethora, drunk with the miracles of its scientific advance, blind to the riches of the world of the spirit, and deafened to the inner Voice by the outer clamor, Western civilization may destroy the old in Islam, but it cannot fulfill the new.

When the shriek of the factory whistle has drowned the voice of the muezzin, and when the smoke-belching chimney has dwarfed the minaret, obscured the sky, and poisoned the air, young Islam will be no nearer to the Kingdom of God. Their bandits will simply forsake the caravan routes of the desert for the safer and more lucrative mercantile and militarist fields.

Nor can the churches of Christendom, as they are today and of themselves, lead the Moslem peoples to that goal. Limited in their vision, separative in spirit, tied to ecclesiastical systems, the churches of themselves if transported en bloc to the Moslem world, would not save it. They have not saved their own civilization. They have not made Christian their own national foreign policies in relation to the Moslem peoples. They have not purged the Western commerce that sells to the East and that grows rich on its oil-wells, but passes by on the other side while the Armenian, stripped and beaten, lies in the ditch of misery.4

I do not mean to suggest by these citations that Huntington borrowed either his title or his ideas, much less his writing style, from Mathews. The little-remembered YMCA worthy was giving voice to the standard Protestant missionary rhetoric of his time. Huntington’s espousal of secular Western values substitutes pugnacity and pessimism for Mathews’ optimism and religious zeal. (Indeed, Mathews’ choice of title plays off of, and energizes, the much better known book title by Arnold Toynbee published three years before: The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilizations.5) For all their differences, however, the coincidental employment of the same phrase for essentially the same subject shows that the anxiety many American observers of the Muslim world have felt ever since the Iranian Revolution is not entirely new. Protestant missionaries, who outnumbered any other group of Americans in non-Western lands and accounted for the great preponderance of American thought about Asia and Africa prior to World War II, harbored an ill-disguised contempt for Islam that looms in the background of today’s increasingly vitriolic debates about Islam and the West.

Huntington’s recoining of the phrase “Clash of Civilizations” successfully captured an array of feelings that had been calling out for a slogan ever since Khomeini toppled the Shah from his throne. Other phrases—“Crescent of Crisis,” “Arc of Instability,” “Islamic Revolution”—had auditioned for the part with indifferent success. No one much disagreed, at least at the level of vagueness that informs most foreign policy posturing, about what it was that needed a name; but compressing it into a single phrase proved difficult. “Clash of Civilizations” caught the imagination because it was dynamic, interactive, innocent in Huntington’s exposition of awkward definitions and boundaries, not transparently bigoted or racist, and vaguely Hegelian in the seeming profundity of its dialectical balance between good and evil. Combined with its author’s eminence as a noted political scientist, and the reputation for sagacious insight commonly ascribed to Foreign Affairs by its subscribers, “Clash of Civilizations” won the prize.

Beyond its surface attraction, however, lay a deeper allure harking back to Basil Mathews’ era. Civilizations that are destined to clash cannot seek together a common future. Like Mathews’ Islam, Huntington’s Islam is beyond redemption. The book on Islam is closed. The strain of Protestant American thought that both men are heir to, pronounces against Islam the same self-righteous and unequivocal sentence of “otherness” that American Protestants once visited upon Catholics and Jews.

The comparison with Protestant views about Catholics and Jews is worth pursuing. Whatever became of the ferocious Protestant refusal to visualize an American future—the future that has actually transpired—in which Protestants and Catholics would agree to disagree on selected matters, but otherwise live in harmony and mutual respect? Symbolically, John F. Kennedy’s 1960 victory in the Democratic primary in largely Protestant West Virginia proved that the American people had a greater capacity for inclusion than their preachers and theologians did. How about the Protestant anti-Semitism that severely constricted the residential, educational, and occupational options of American Jews and permitted a virulent hater like Henry Ford to be viewed as a great man? From the 1950s onward, with the reality of the Holocaust and the ghastly consequences of European anti-Semitism ever more apparent, the term “Judeo-Christian civilization” steadily emerged from an obscure philosophical background—Nietzsche used “Judeo-Christian” scornfully in The Antichrist to characterize society’s failings—to become the perfect expression of a new feeling of inclusiveness toward Jews, and of a universal Christian repudiation of Nazi barbarism. We now use the phrase almost reflexively in our schoolbooks, our political rhetoric, and our presentation of ourselves to others around the world.

The unquestioned acceptance of “Judeo-Christian civilization” as a synonym for “Western civilization” makes it clear that history is not destiny. No one with the least knowledge of the past two thousand years of relations between Christians and Jews can possibly miss the irony of linking in a single term two faith communities that decidedly did not get along during most of that period. One suspects that a heavenly poll of long-departed Jewish and Christian dignitaries would discover majorities in both camps expressing repugnance for the term.

Substantively, a historian would argue, the term is amply warranted. Common scriptural roots, shared theological concerns, continuous interaction at a societal level, and mutual contributions to what in modern times has become a common pool of thought and feeling give the Euro-American Christian and Jewish communities solid grounds for declaring their civilizational solidarity. Yet the scriptural and doctrinal linkages between Judaism and Christianity are no closer than those between Judaism and Islam, or between Christianity and Islam; and historians are well aware of the enormous contributions of Muslim thinkers to the pool of late medieval philosophical and scientific thought that European Christians and Jews later drew upon to create the modern West. Nor has there been any lack of contact between Islam and the West. Despite periods of warfare, European merchants for centuries carried on a lively commerce with the Muslims on the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean; and the European imagination has long teemed with stories of Moors, Saracens, and oriental fantasy. Politically, fourteen of today’s thirty-four European countries were at one time or another wholly or partially ruled by Muslims for periods of a century or more. The historians of these countries sometimes characterize these periods of Muslim rule as anomalies, inexplicable gaps in what should have been a continuous Christian past, or as ghastly episodes of unrelenting oppression, usually exemplified by a handful of instances. In reality, however, most of the people who lived under Muslim rule accustomed themselves to the idea, and to the cultural outlook that went with it, and lived peaceable daily lives.

Our current insistence on seeing profound differences between Islam and the West, what Huntington calls civilizational differences, revives a sentiment of great antiquity. As in the past, dramatic events have catalyzed this reawakening. The fall of America’s friend, the Shah of Iran, and the anguishing detention of American diplomatic personnel in Tehran in 1979, were but a prelude to the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon of September 11, 2001. However, they gave us a twenty-year head start on worrying about Muslims conspiring to carry out violent political acts professedly based on religious principles. Previous cataclysms echo in the background of these events: the fall of Crusader Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187, the fall of Byzantine Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, and the nearly successful Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529 are but three. The aftermath of each of these events brought with it a shudder of horror at what might transpire should the Muslims prevail on a grander scale. The historian Edward Gibbon gave this fear its classical expression in the eighteenth century in his discussion of what might have happened if a Saracen raiding party from Spain had not suffered defeat at the hands of Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours in 732. “Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pupils might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.”6

Here is how a Lutheran pamphleteer expressed this sentiment in 1537 when many Europeans thought a new and possibly successful siege of Vienna was imminent:

Christians should also take comfort in the knowledge that the Turkish Empire is God’s enemy, and that God will not allow it to annihilate the Christians. Although God has caused this empire to arise in these last times as the most severe of punishments, nonetheless He will not allow the Christians to succumb completely, and Mahomet will not rule alone in the whole world … Therefore those who fight against the Turk should be confident … that their fighting will not be in vain, but will serve to check the Turk’s advance, so that he will not become master of all the world.7

It may well be that past episodes of Islamophobia did more good than harm. They rallied frightened people and encouraged them to seek refuge from despair in their religious faith, and the military responses they contributed to ideologically were probably no bloodier than they would have been anyway. By good fortune—and Christian antipathy toward foreigners—few Muslims were resident in European Christian lands so there wasn’t anyone local to kill when preachers whipped their congregations into an Islamophobic froth. The Jews, of course, had worse luck when the arrow of Christian alarm pointed in their direction, as it did many times, including the time of the Black Death of 1348–1349. “In the matter of this plague, the Jews throughout the world were reviled and accused in all lands of having caused it through the poison which they are said to have put into the water and the wells … and for this reason the Jews were burnt all the way from the Mediterranean into Germany.”8

We are no longer living in medieval isolation, however. Large Muslim minorities reside and work in almost every country in the world, including every European land and the United States and Canada. The potential for tragedy in our current zeal for seeing Islam as a malevolent Other should make us wary of easy formulations that can cleave our national societies into adversarial camps. A number of years ago a government adviser from Belgium visited with a group of scholars at the Middle East Institute of Columbia University. She was looking for ideas on how to induce the Muslims living in Belgium to become more like “normal” citizens. They were more than welcome to live in Belgium, she averred, but surely it would be best if they were distributed a few here and a few there so that they would not constitute a visibly different social group. Their headscarves and beards would not be so noticeable, and they would not perturb the Belgian national community. As we were sitting in a room overlooking Harlem, it was pointed out to her that clustered communities of difference do not always have to be thought of as ghettos. Socially visible minorities are not only a given in American life, but also a wellspring of cultural creativity. Perhaps in time the folks with the headscarves and beards would become a parallel resource for Belgium.

The question confronting the United States is whether the tragedy of September 11 should be an occasion for indulging in the Islamophobia embodied in slogans like “Clash of Civilizations,” or an occasion for affirming the principle of inclusion that represents the best in the American tradition. The coming years may see wars and disasters that dwarf what we have already endured. But they must not see the stigmatization of a minority of the American population by an overwrought majority whipped up by the idea that that minority belongs to a different and malign religious civilization. “Clash of Civilizations” must be retired from public discourse before the people who like to use it actually begin to believe it.

“Islamo-Christian Civilization”

To the best of my knowledge, no one uses, or has ever used, the term “Islamo-Christian civilization.” Moreover, I would hazard the guess that many Muslims and Christians will bristle at the very idea it seems to embody, and other readers will look suspiciously at the omission of “Judeo-” from the phrase. I can only hope that they will withhold final judgment until they have considered my “case” for introducing the term.

To begin with, why not “Islamo-Judeo-Christian Civilization”? If I were looking for a term to signal the common scriptural tradition of these three religions, that might be an acceptable, albeit awkward, phrase. But for this purpose, phrases like “Abrahamic religions,” “Children of Abraham,” and “Semitic scriptualism” do quite well. I am trying to convey something different. The historical basis for thinking of the Christian society of Western Europe—not all Christians everywhere—and the Muslim society of the Middle East and North Africa—not all Muslims everywhere—as belonging to a single historical civilization goes beyond the matter of scriptural tradition. This historic Muslim-Christian relationship also differs markedly from the historic Jewish-Christian relationship that is more hidden than celebrated in the phrase “Judeo-Christian Civilization.” European Christians and Jews—no one includes the Jews of Yemen or the Christians of Ethiopia in discussions of “Western” origins—share a history of cohabitation that was more often tragic than constructive, culminating in the horrors of the Holocaust. Cohabitation between Muslims and the Christians of Western Europe has been far less intense. Rather than the unequal sharing of social, political, and physical space underlying the Jewish-Christian relationship in Europe, which may fruitfully be compared with the historic Muslim-Jewish relationship in the Middle East and North Africa, the term “Islamo-Christian civilization” denotes a prolonged and fateful intertwining of sibling societies enjoying sovereignty in neighboring geographical regions and following parallel historical trajectories. Neither the Muslim nor the Christian historical path can be fully understood without relation to the other. While “Judeo-Christian civilization” has specific historical roots within Europe and in response to the catastrophes of the past two centuries, “Islamo-Christian civilization” involves different historical and geographical roots and has different implications for our contemporary civilizational anxieties.

Let it also be noted that there are two other hyphenated civilization that deserve discussion, but that will not be discussed here. A treatment of “Judeo-Muslim civilization” would focus on scriptural, legal, and ritual connections between these two faiths; on Jewish communities in Muslim lands and their literatures in Judaeo-Arabic and Judaeo-Persian; and on the profound inte...