![]()

The Colonial Past

![]()

THE EMPIRE AND ITS ANTIQUITIES: TWO PIONEERS AND THEIR SCHOLARLY FIELDS

During the one hundred years of British dominion in India, the Government had done little or nothing towards the preservation of its ancient monuments, which, in the total absence of any written history, form the only reliable source of information as to the early condition of the country. … Some of these monuments … are daily suffering from the effects of time, and … must soon disappear altogether, unless preserved by the accurate drawings and faithful descriptions of the archaeologist.

… Hitherto, the Government has been chiefly occupied with the extension and consolidation of empire, but the establishment of the Trigonometrical Survey shews that it has not been unmindful to the claims of science. It would redound equally to the honour of the British government to institute a careful and systematic investigation of all the existing monuments of ancient India.

—COL. A. CUNNINGHAM,

Bengal Engineers, to the governor general, Lord Canning

THIS CHAPTER IS ABOUT beginnings and foundations. Like most beginnings that mark out the “modern” era in Indian history, my starting points, too, locate themselves squarely in the country’s colonial past. The story, as is typical, begins with the first British civilians and officers who took up the cause of retrieving India’s “lost” history from the ancient ruins and monuments that pervaded the terrain, who also saw themselves as conferring order and system on the modes of studying and interpreting these structural remains. Their careers thus signal the inauguration of the modern scholarly fields of Indian art, architecture, and archaeology, each taking its particular shape out of the umbrella category “antiquities” that had first commanded Western attention. The term “antiquities” appears here as a distinctly Western cognitive entity with a specific nineteenth-century history, whose usage and deployment in colonial India would define the way antiquarianism would slowly prepare the grounds for new disciplinary specializations. As an all-encompassing denomination (including everything from whole monuments to the smallest architectural fragments, from manuscripts to sculptures, coins, and inscribed slabs), the concept of antiquities becomes a marker of the period’s persistent bid for complete, comprehensive knowledge—knowledge that would thereafter allow the concept to be superseded, refined, particularized.

This story about the beginnings of new Western scholarship is also about the launch of the first institutional claims for the care, conservation, and custodianship of Indian antiquities. The full contours of this story will unfold over the subsequent chapters. The opening extract from a memorandum of 1861, placed before the government of India by the army-engineer-turned-field-archaeologist Alexander Cunningham, pointedly underlines these overlapping colonial demands of knowledge, control, and custody. It also clearly encapsulates the trajectory of “beginnings” that this chapter addresses. The memorandum is frequently cited to mark the founding moment of the modern profession of archaeology in colonial India. What is vital is the way it not only prioritizes antiquities as the “only reliable source” for India’s absent history but also foregrounds a new disciplinary expertise—that of the archaeologist—in the process of extracting history from these ruins. It places a special weight on the accuracy of description and documentation, on the production of a thorough visual and textual record as an essential requisite to an ordered body of knowledge about these monuments. Simultaneously, it gives voice to another critical need: that of replacing random individual initiatives by a systematized governmental enterprise.

As Cunningham wrote, “everything that has hitherto been done in this way has been done by private persons, imperfectly and without system.”1 Only an institutional survey, he felt, could make for a more scientific pattern of archaeological investigation. Cunningham’s memorandum can be seen to form a bridge between two evolving histories. It augurs the passage from an earlier spectrum of individual explorations (that included much of Cunningham’s initial career in India) to a period that saw the setting up of the Archaeological Survey of India and extensive programs for the survey, documentation, and conservation of ancient buildings. This chapter locates itself at the nodal point of this historical conjuncture to explore the grounds of transition from the one phase to the other. My main concern lies with the interlocked trajectory of travel, survey, and scientific knowledge that so prominently shaped the scholarship on Indian antiquities during this period. What this also throws into sharp focus is the role and self-fashioning of pioneer European scholars in the virgin field of the colony: the lineages they claimed for themselves and the singularity and authority of the positions they staked.

This chapter is about two such pioneers, working in the vast untapped field of Indian antiquities—James Fergusson (1808–86) and Alexander Cunningham (1814–93)—whose authority would be grounded in the experiences of their extensive travels and explorations. Both found themselves charting new territories and routes and laying out a new map of India’s ancient historic sites. Theirs were two careers unfolding over the middle years of the nineteenth century, in parallel and often at a tangent to each other. And out of them we can mark the forming of two distinct disciplines—architectural and archaeological studies—each revolving around a different method of attaching histories to monuments. As is widely acknowledged, it was Fergusson who gave India its first comprehensive history of architectural forms and styles, while it was Cunningham who opened up its ancient sites to the specialized investigations of field archaeology.

What is less known is the way both these figures also played a foundational role in the creation of what would become the definitive visual and textual archive on the subject of India’s historical monuments. James Fergusson propelled into existence the earliest, most comprehensive pool of images (ranging from plaster casts and drawings to lithographs, engravings, and photographs) on India’s architectural heritage. The drawing and photographing of monuments becomes with him an integral appendage of scientific scholarship. The production of an accurate image became crucial to the exercise of conceptualizing a history of Indian architectural styles, making architectural evidence a key determinant of Fergusson’s analytical approach. In addition, the photograph as a record became central to the off-site production and propagation of scholarly authority in the field. In parallel, over the same years, what the inveterate surveyor-explorer Alexander Cunningham generated from the sites was a voluminous body of written descriptions and reports that meticulously narrated the routes of travel and the topographical, historical, and archaeological details of each excavated site alongside every step of the investigative procedure. By the late nineteenth century, the visual documentation of monuments could take its place within an equally extensive textual corpus of site reports. These reports are what would become Cunningham’s prime legacy to the field and still stand as the main source base for the history of Indian archaeology.

James Fergusson and His Architectural Trail

The “Picturesque” Lineage

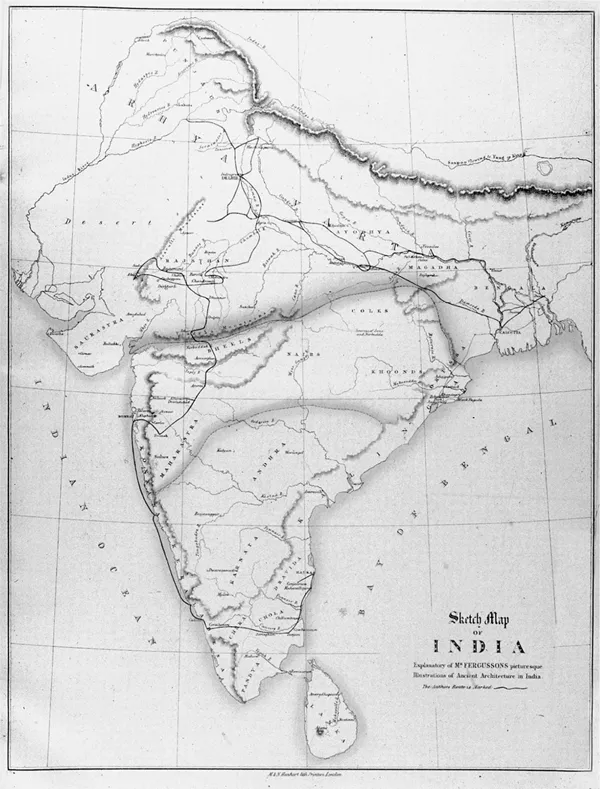

Let me begin with the career of the Scotsman James Fergusson, who at an early age joined a mercantile establishment in Calcutta and soon moved on to found his own indigo factory in Bengal.2 Between 1835 and 1842, he embarked on his arduous travels across the length and breadth of the Indian peninsula, indulging a different passion. Like generations of other traveling Europeans who converged on India in search of the “picturesque,” Fergusson was driven by the same urge to discover and document the exotic lands of the empire. At the same time, he was also on a more specialized trail: armed with a diary, a draftsman’s pad and a camera lucida, his project was to survey as exhaustively as possible examples of old Indian buildings.3 His tour, in all its phases, was thus routed along architectural sites (see fig. 1.1). And its primary intention was to assemble on-the-spot notes, sketches, and photographic impressions of the monuments he encountered.

In retrospect, Fergusson’s project can be seen to stand at the critical crossroad between an earlier flourishing genre of “picturesque” landscape painting and a subsequent genre of scholarly documentation. On the one hand, the timing of his tours places him in close and direct lineage from the traveling scenic painters in colonial India. On the other hand, the nature of his work also foreshadows the birth of a new disciplinary field: the history of Indian architecture. Long before the institution of government surveys, Fergusson can be seen to be playing out his heroic role as a “one-man architectural survey, … drawing, making plans, taking careful notes, and above all, doing some very hard thinking.”4 The firsthand acquaintance and information he marshaled during these travels would serve as the basic fund for all his subsequent writing on a subject he ordered and systematized as the History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (1876).5 As the author of the first comprehensive history of Indian architecture, Fergusson is thus invariably prefigured in the amateur traveler of the 1830s. While the account of his travels reads as a prehistory of his inauguration of the academic discipline, the discipline itself (Fergusson’s authority and methodology as its founder-scholar) would constantly authenticate itself on the experience of these first explorations.

FIGURE 1.1 Map of Fergusson’s architectural tour through India, undertaken between 1837–39. Source: James Fergusson, Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture in Hindostan (London: Hogarth, 1848).

Fergusson, much more than Cunningham, was steeped in a sense of the loneliness and novelty of his own enterprise. When he first set out on his travels, he found himself surrounded by “darkness and uncertainty,” with no account whatsoever of any art or architectural history of India to guide him or any criteria by which to judge the age and style of the buildings he encountered. There may have been a few others before him who had drawn or described some of the buildings he visited, but “none,” he declared, had “been able to embrace so extensive a field of research as I have”6 Such a claim rested primarily on the premium he placed on the intensity of his own observations of the monuments and on the correctness of his own delineations as against those of other traveling artists before him. He had in mind, primarily, the famous scenic views of India’s landscapes and monuments (the Oriental Scenery series) produced by Thomas and William Daniell. Intended to be primarily “pleasing artistic compositions,” these images were seen to be lacking in the value of “information and instruction,” and it was the latter value that constituted Fergusson’s new, obsessive preoccupation.7 I would, however, begin by situating Fergusson’s initial work within the very lineage he wished to break out of. The compulsions of the “picturesque” (as the dominant representational mode for the colonial traveler of this period) continued to weigh heavily on Fergusson, despite his disclaimers and counteremphasis on accuracy of description. It is this inherited aesthetic frame that was transmuted, in him as in many others, into a complementary agenda for detailed survey and documentation.

It is not a matter of minor detail that Fergusson chose to title the first book that followed from his travels Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture in Hindostan. Published in London in 1848, soon after his return to England, it was the direct product of the notes and sketches from his tours across India. The book is a scholarly reenactment of the journey: it consciously fills out, organizes, and orders the private record the author left behind in his travel diaries of the years 1837–39.8 Juxtaposed against each other, the diaries and the book reflect the first phases of a transference of the experiences of travel into visual and textual narration, of a direct observation of monuments into a discourse on history and style. It remained, however, an incomplete and uneasy transference, trapped in a lingering engagement with the “picturesque.” For Fergusson, the “picturesque” still constituted the only available frame of representation, the medium through which his travels and observations could translate into a larger historical project.

The notion of the “picturesque” had, by then, an established artistic history and status.9 It held sway as the main metaphor both for the images produced of India and for the journeys undertaken in their quest. The most famous of such “picturesque” voyages had been undertaken in the late eighteenth century, first by William Hodges and then by the uncle-and-nephew...