![]()

PART I

TOWARD A THEORY OF THE GANG AS A SOCIAL MOVEMENT

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE STUDY

The Method

It is probably safe to say that the majority of studies of inner city inhabitants, particularly those that focus on members of youth gangs, have been carried out within the tradition of positivistic social science.1 With natural science as the paradigm of good research, a premium has traditionally been placed on the value neutrality of the observer, the scientific rigor of the methodology, the unpolluted character of the data, and the generalizability of the findings, all with the aim of proving or disproving testable hypotheses (see Lincoln and Guba 1985). In this way, the gang phenomenon, whether it is understood as a delinquent organization (Klein 1971), an interstitial peer association (Thrasher 1927) or a violent near-group (Yablonsky 1963), has consistently been treated as an objectified unit of analysis and the subject of an ever-growing list of truth claims.2 Few researchers, however, ever openly discuss the underlying assumptions contained in their written accounts of gangs and gang members, even though, for the most part, they occupy completely different racial and class worlds from those of their subjects.

In contrast to this scientistic conception of knowledge production and social investigation, what Mills (1959) and others have termed “abstract empiricism,” replete with its male, white, middle-class biases and its discursive appropriation in the service of bureaucratic agencies (Foucault 1977), we have chosen an unabashedly critical approach to the ethnographic study of gangs and their members. Basing our work on the philosophical critiques of normative social-science practices, especially those which emanated from within the neo-Marxian traditions of the Frankfurt School (e.g. Adorno 1973, 1976; Benjamin 1969; Marcuse 1960, 1964, 1978) and later developed by an array of poststructuralist and postmodernist discourses (see Kincheloe and McLaren 1994), our interrogation problematizes relations between the researcher and the researched and resists the authority of mainstream social science. Thus, rather than accept as given the working definitions, normative value systems, and categories of social and cultural action that are implicit in orthodox gang canons, our orientation begins from the premise that all social and cultural phenomena emerge out of tensions between the agents and interests of those who seek to control everyday life and those who have little option but to resist this relationship of domination. This fundamentally critical approach to society seeks to uncover the processes by which seemingly normative relationships are contingent upon structured inequalities and reproduced by rituals, rules and a range of symbolic systems. Our approach, therefore, into the life of the ALKQN, is a holistic one, collecting and analyzing multiple types of data and maintaining an openness to modes of analysis that cut across disciplinary turfs.

In addition, we have chosen a collaborative mode of inquiry in order to expressly participate with the subjects in an active, reciprocal and quasi-democratic research relationship (Touraine 1981).3 By this approach, we mean the establishment of a mutually respectful and trusting relationship with a community or a collective of individuals which: (1) will lead to empirical data that humanize the subjects, (2) can potentially contribute to social reform4 and social justice, and (3) can create the conditions for a dialogical relationship (Bakhtin 1981; Freire 1970) between the investigator(s) and the respondents.5

In the Right Place at the Right Time

Our relationship with the ALKQN began in 1996, at a time when the ALKQN was reeling from the arrest and indictment of its leader, Luis Felipe, aka King Blood, and another thirty-five members of the group’s hierarchy. It was clear to a number of the free and incarcerated leaders that the police and political establishments of the federal government, the state, and the city would not stop their assault on the organization regardless of how many leaders were successfully prosecuted. Certainly, this was an accurate assessment of current police thinking and as long as the group remained committed to its gangster past it gave the combined forces of the state every legal and social justification to destroy the organization. Thus, the new leadership, under Antonio Fernández, began to come to terms with this highly threatening situation and, with the support of King Blood, set about looking to accomplish at least two immediate goals: (1) to establish ties with activist members of the community, particularly Latinos, who would be willing to work in a supportive, nonjudgmental way with the group, and (2) to find public or private spaces where the group could meet, safe from the constant surveillance and harassment of the police.

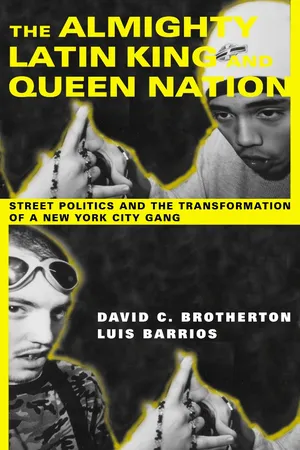

FIGURE 1.1 The two authors with Latin Kings and Queens.

It was at this time that one of the coauthors, Luis Barrios, was approached about offering the ALKQN a space to have their meetings.6 Barrios agreed that his church could be used for this purpose as long as the group: (1) allowed him to be present during the meetings; (2) agreed to open the meetings to the public; and (3) was serious about involving the group in the community’s social and political issues. The ALKQN concurred with all the stipulations and became officially part of the Latino/Latina ministry of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Manhattanville, Central Harlem in 1996.

Following this development, one of the rare occasions that a church in New York City (or anywhere else) had opened its doors to the group, Barrios, with the approval of the ALKQN leadership, invited his colleague, Brotherton, to the church with a view to studying and documenting this movement in its early stages. For Brotherton, the rich description that Barrios offered of this organization and its proposed sociopolitical agenda was in marked contrast not only to what he had observed on the West Coast,7 but to what he had found in the current literature on gangs. It was, to quote Burawoy (1991), an “anomalous outcome,” and appeared to contradict the theoretical paradigms within which nearly all gang-focused social scientists were working.

Negotiations, Negotiations, and More Negotiations

We’re not gonna let ourselves be represented by academics like we were born in the barrio yesterday. We ain’t fish in a bowl to be looked at and dissected—you better get that straight! We’re not here in your laboratory, doing your bidding, helping your careers. We ain’t nobody’s fools and we’re not gonna be used by no poverty pimps. If you wanna work with us that’s fine but you ain’t gonna take us for granted. We don’t care what the rules of the games are.… We gonna change the game.

[Informal interview with King H.]

After further meetings with the leaders of the ALKQN, in which we talked about our preliminary findings, the authors developed a research proposal that the group could work with, similar to the research strategy that Lincoln and Guba (1985) call the “hermeneutic-dialectic.”8 Thus, we would focus on the learning development of the membership and the role that the organization was playing as a site of informal education. We felt that most studies of gangs were overly focused on acts of delinquency and crime and neglected, almost entirely, the relationship that all young people have with myriad systems of knowledge, be it school-based training and socialization processes or the inculcation of values, norms, and symbolic codes that comes with gang membership.

At each stage of the research process, however, we were involved in intense negotiations with different members of the group regarding the shape that the research would take, its claims to authenticity, its uses, and its ownership. Who would benefit from the knowledge? Who would do the writing? What questions could be asked and of whom? Such issues were constantly raised by the group’s leading members and the researchers’ long discussions with them often took the form of power plays between the organization and the researchers. This was particularly so now that the group was taking its public self very seriously and was attempting to control and reappropriate its image in the face of what the group’s Spiritual Advisor (Santo) called the “academic-correctional-industrial complex.”

These exchanges and debates, which centered on the nature and boundaries of the research, were complex and multi-layered, not least because many of the members still resisted the idea of the organization’s research and media involvement. For even though the organization was moving rapidly to open its doors to more scrutiny and was adopting radical political positions that, in time, would push it to the forefront of the city’s grassroots resistance to welfare and education cuts, many members were loath to compromise the autonomy that came with the group’s old practices of complete secrecy. Furthermore, the research was taking place during a time when the organization was under some form of surveillance virtually twenty-four hours a day (see chapter 12).

Eventually, in 1997, Brotherton, Barrios, and the leaders of the ALKQN, principally Antonio Fernández and King H., agreed that the study would be a viable way for the organization to (1) tell its story (in a way that the media were unlikely to do) and (2) document this transitional phase not only as a service to the ALKQN but to the Latino/a community in general. This consensus meant that we could now interview a cross-section of the membership and attend a variety of meetings that included weekly branch meetings of the youth section(s) (known as the Pee Wees) and the womens’ section (known as the Latin Queens), monthly general meetings called “universals” (which have all been recorded either on audio or video tape), and socials, such as weddings, baptisms, funerals, and birthdays. It was also agreed that we would collect and collate all the monthly newsletters of the organization, all music recordings distributed under the organization’s name, and that we would develop a database of media stories dating back to the early 1980s. In addition, the leadership was keen to have designated Latin Kings and Queens help us to “map” areas, which included photographing local neighborhoods where large numbers of the membership were living.

Flexible Data Collection and Innovative Methods

A thousand law enforcement officials fanned out across New York City before dawn yesterday and struck what the authorities called a crippling blow to the Latin Kings gang, seizing 94 members and associates, including top leaders, on charges ranging from possessing guns and drugs to conspiring to commit murders.… While more than half of the state and Federal charges filed yesterday were felony charges, there were no homicide allegations, and many of the charges were misdemeanors.

New York Times, 5/15/98:B3

The quote above from the New York Times gives some indication of the rapidly changing social and political terrain within which the project was taking place. As participant observers in the action of the group we, of course, needed to follow as closely as possible the multiple forms of struggle that were being waged between the state and its agents and the group’s members. Consequently, we had to be prepared to gather our data in whatever set of circumstances were presented to us without becoming embroiled in the internal politics of the group or, alternatively, being made timid by the relentless encroachments of the police and members of the security state.

We chose, therefore, to hire a leading member of the group to consult with us throughout the project’s duration. In practical terms this ensured: (1) the continuity of the project, (2) the permanent and mutually understood presence of a “gatekeeper,” (3) the provision of a cultural broker to help us interpret unfamiliar meaning systems, and (4) the project’s ethical integrity with the targeted community. To this end, we hired the leader of the ALKQN, Antonio Fernández, who worked as a part-time paid research assistant during six months from July 1998 (when he was under house arrest) until just prior to his incarceration in January 1999.9 In addition to Fernández, several other Kings and Queens, among them King H., King M., Queen D., and Queen N., helped in the recruitment of respondents from both the adult and youth sectors of the group. Further, both Fernandez and King H. consistently responded to our analyses of the data, offering their own interpretations while also suggesting new research areas.

The interviews, most of which were in English with twelve in Spanish, were carried out by Brotherton and Barrios, along with three field researchers, Juan Esteva, Camila Salazar, and Lorinne Padilla, and a fourth affiliate researcher working on his own independent Latin Kings’ project on Long Island, Louis Kontos.10 Various sites were used to do the interviews, nearly all of which were tape recorded and later transcribed, but the majority took place at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Harlem, in members’ homes, at John Jay College in Manhattan, in local diners, or at outdoor sites during group meetings (only one interview was done in prison). Each participant was provided with a voluntary consent form before the interview, assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the interview process, and paid twenty-five dollars, which was deposited in a general fund administered by the organization’s leadership. Throughout this book we have adhered to the principle of disguising both Kings and Queens by identifying them only by an initial, with the exception of King Tone. We found it almost impossible to conceal his identity in the text and so, with his agreement, we have printed his name in full.

The project yielded sixty-seven individual life history interviews covering a range of the group’s membership, i.e., males and females, young and old between the ages of sixteen and forty-eight, longstanding members and new recruits, members in the leadership and those in the rank-and-file. In addition, several leading members who were at the heart of the changes in the organization were interviewed multiple times throughout the research period. Further, we interviewed a wide variety of “outsiders,” i.e., those who had interacted with the group in different capacities. Outsiders included nongroup family members, members of the clergy, leaders of nonprofit community groups, defens...