eBook - ePub

Plants Invade the Land

Evolutionary and Environmental Perspectives

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

What do we now know about the origins of plants on land, from an evolutionary and an environmental perspective? The essays in this collection present a synthesis of our present state of knowledge, integrating current information in paleobotany with physical, chemical, and geological data.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Plants Invade the Land by Patricia Gensel, Dianne Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geology & Earth Sciences. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Geology & Earth Sciences1

Introduction

The invasion of the land by organisms is one of the major events in the evolution of life, permanently altering the conditions on Earth and essentially resulting in the diversification of the kingdom Plantae as presently defined. As a result of recent research, remains of terrestrial plants occur as early as basal Ordovician. The record of terrestrial animals now dates from the Middle–Late Silurian, and an earlier timing is possible. It has been postulated for some time that fungi and other types of organisms also may have inhabited the land since at least 450 million years ago. That terrestrial plants strongly influenced environmental conditions on Earth, essentially initiating major global change, is well established, but details remain to be worked out. This book focuses on a current understanding of the fossil record of land plants and other organisms; recent environmental interpretations based on geology, geochemistry, and fossils; assessment of the impact of plants on geological processes; and the nature of interactions of plants with fungi, animals, and their environments.

The chapters are based on talks given at a symposium held during the Fifth International Organization of Paleobotany Conference in 1996, and a few more authors were invited to cover additional pertinent topics. Our goals for the symposium and this book are to consider the present state of knowledge and recent developments concerning the evolution of plants on the land from both an evolutionary and an environmental (geological) perspective, including the interplay of plants and their environments, or plants and other coeval organisms (animals, fungi), and to suggest future avenues of investigation. The time span is Ordovician—Upper Devonian, with emphasis on Silurian through Middle Devonian, thus covering the period of major global change that resulted from the diversification of plants and their impact on the environment. Many of the chapters are synthetic, but these also include new primary data, while others document new findings. We hope this combination of approaches and topics presents a comprehensive view of what we presently know about early terrestrial organisms and their environment and will serve both as a useful reference and as a stimulus for additional research.

The first several chapters set the stage by documenting early land inhabitants ranging from protistan to plant and animal; this is done via a survey of the record of earliest terrestrial plants (basal Ordovician to middle Devonian), the description of new taxa or newly discovered plant structures, and assessment of biogeographical patterns. Later chapters deal with data and interpretation of critical structural, biochemical, and/or physiological adaptations necessary for terrestrial habitation; environmental parameters such as atmosphere and substrate types; plant—animal—soil interactions; and impact of environmental change caused by plants inhabiting the land. Themes emerging from these chapters include the following:

1. The value of careful study of morphological and anatomical detail for inferring growth patterns and ecological adaptations, and for whole-plant reconstruction and taxonomic clarity.

2. The acquisition of new data. New data about the basal regions [i.e., rhizomes (horizontal stems) and rooting structures] in early land plants are documented more extensively than previously, both from a plant structural and from an ecological/geological viewpoint. Spores as an important source of data about presence, distribution, lineage, and evolutionary change in early land plants also are highlighted.

3. The recognition of up-to-now overlooked evolutionary events. This is especially significant for the Middle Devonian, which is more than a continuation of what happened in the Late Silurian–Early Devonian. Turnover of taxa and a radiation of trimerophyte-derived lineages and new types of lycopsids, and the beginnings of stratification of vegetation with the onset of small tree–sized plants, were initiated near the end of the Emsian and amplified during the Middle Devonian.

4. The power of integration of several types of data. Considering the dispersed spore record with the megafossil record of early land plants has altered ideas on timing of origin and may aid in interpretation of affinities of early embryophytes. Considerations of the extant closest putative relative(s) to land plants and adaptations to terrestriality may show us ways that the invasion of land was achieved. The animal record and the plant record both contribute uniquely to examining the probable role of animals in early terrestrial ecosystems vis-à-vis plants—Were there any early herbivores? What do the sediments tell us about early terrestrial environments and biota, and what are the possible factors controlling the distribution of taxa on the landscape, biogeochemical changes in early soils, and contributions of both to the early atmosphere? Attention is given to root–soil interactions, to plant–atmosphere interrelationships, and to biochemical pathways that may have been important to the success of plants on the land. How plants may have influenced events in other parts of the ecosystem (e.g., as causal factors for the Middle–Late Devonian marine anoxic events and biotic crises) is also developed.

These chapters demonstrate that while the current state of knowledge is sufficient to address broad questions and provide new information, much more primary data and more integrated studies are needed. Continuation of such studies and incorporation of new approaches should yield even more insights into the nature and dynamics of early terrestrial ecosystems.

2

Embryophytes on Land: The Ordovician to Lochkovian (Lower Devonian) Record

This chapter is primarily concerned with the documentation of the record of land plants from their earliest occurrences in the Ordovician to the end of the Lochkovian in the Lower Devonian. It covers the initial radiation of the embryophytes in the Ordovician; the emergence of tracheophytes, including the lycophytes, in the Silurian; the proliferation of axial plants with terminal sporangia around the Silurian–Devonian boundary; and, at the end of the Lochkovian, the first major radiation of the zosterophylls. The record remains a very patchy one and makes any conclusions on phylogenetic relationships, evolutionary and migration rates, and global distribution highly conjectural. The fossils themselves are usually very fragmentary, the plants sometimes represented by spores only, so that whole-plant reconstructions are speculative and concentrate on the distal aerial parts. There is very little, if any, information on possible subterranean parts, although the earliest lycophytes are presumed to have roots. Estimates of primary productivity and trophic relationships with consumers and decomposers in the early terrestrial ecosystems have very little factual foundation (see chapter 3). Indeed, although modeled concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide in the Phanerozoic emphasize the dramatic impact of plants on land via increase in chemical weathering (chapter 10), quantitative data on coeval vegetation and extant analyses are sadly lacking. But reservations/inadequacies such as these should not obscure the progress in the last decade in documenting and understanding early phases of land plant vegetation.

The earliest direct evidence for land plants comprises spores and fragments (phytodebris) that were preserved in considerable numbers in a variety of Ordovician and Early Silurian environments, both continental and marine. Fossils of the producers are first recorded in the Llandovery (Early Silurian) some 35 million years after the first microfossil records, but at approximately the same time as the first unequivocal trilete monads believed to derive from tracheophytes.

THE MEGAFOSSIL DATABASE

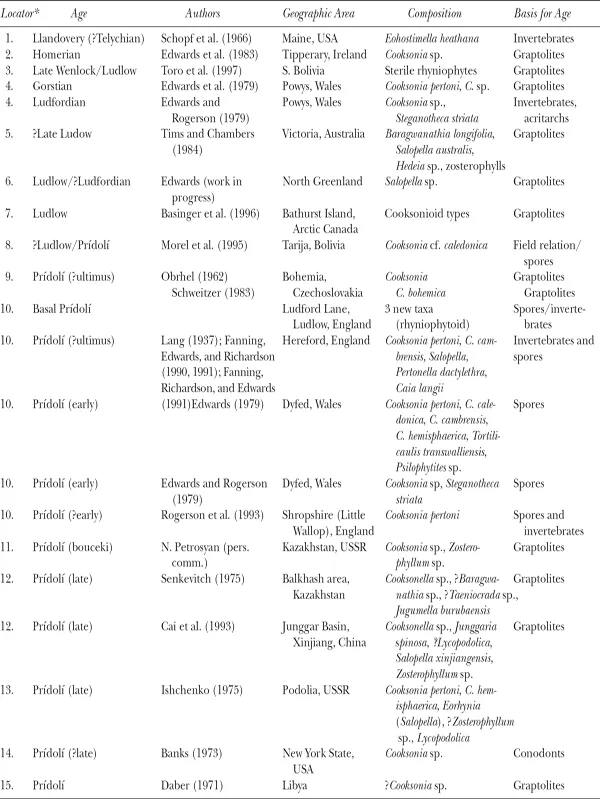

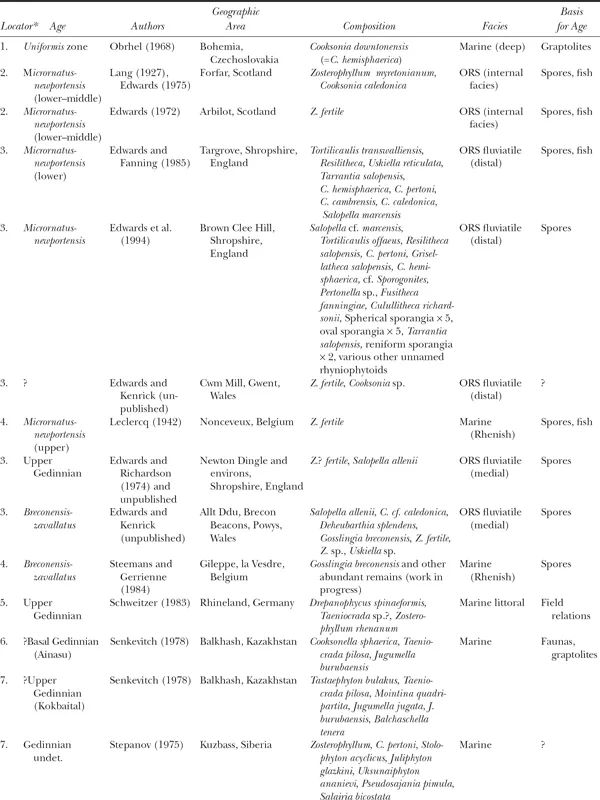

Since Edwards (1990) compiled a database for Silurian and Gedinnian (Lochkovian) assemblages (tables 2.1, 2.2), developments have included both new and paleogeographically satisfyingly widespread localities, and additions or revisions to existing assemblages. These are summarized next; assemblages described from localities 1 to 4 are new.

1. Bathurst Island, Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Basinger et al. 1996)

Ludlow to Pragian rocks have yielded abundant, well-preserved assemblages dated by graptolites. The Ludlow examples in the lower Bathurst Island Beds contain the oldest fertile plants of vascular plant aspect in the New World. One example is a smooth main axis about 2 mm in diameter with alternate fertile complexes. Each comprises a sporangium, oval in face view, with a possible narrow marginal band and subtended by a short, presumed distally curved axis or stalk that increases in diameter below the sporangium. It thus broadly resembles a Cooksonia caledonica sporangium in shape, while sporangial organization is closer to a Zosterophyllum and is more complex than coeval Cooksonia. In this preliminary report, plant localities are also recorded in the uppermost Lochkovian in the upper member of the Bathurst Island Beds, a time of major diversification in other parts of the Old Red Sandstone Continent (e.g., Allt Ddu, Brecon Beacons, in Wellman, Thomas, et al. 1998).

Table 2.1. Silurian localities with plant megafossils

* Locations are noted by numbers on figures 2.5 and 2.6.

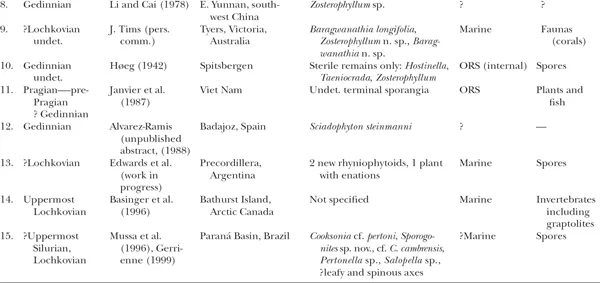

Table 2.2 Lochkovian localities with plant megafossils

* Locations are noted by numbers on figures 2.7 and 2.8.

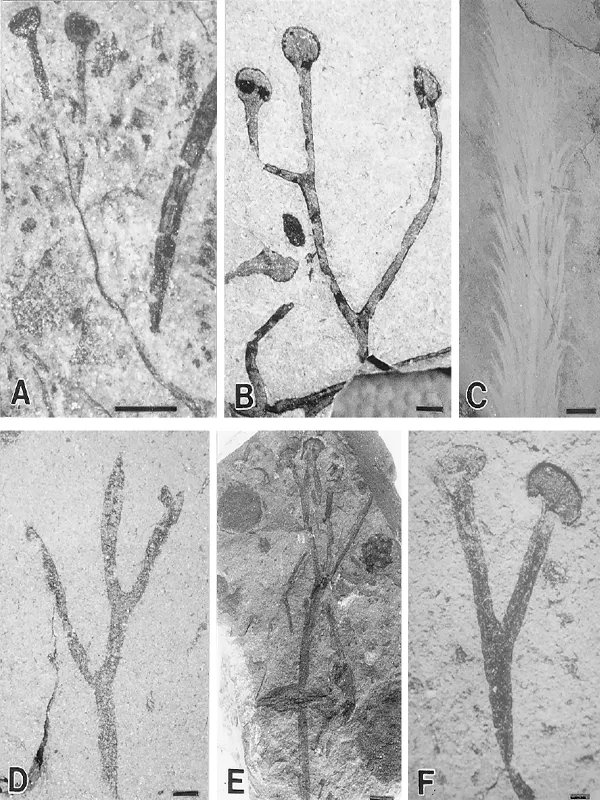

2. Southern Bolivia (Morel et al. 1995; Toro et al. 1997)

Dating is less secure, but field relationships and hence indirect invertebrate evidence points to an upper Ludlow-Prídolí age for the Kirusillas Formation at Tarija, southern Bolivia, which contains abundant plant debris at certain horizons and three well-preserved specimens of Cooksonia with marginal thickening characteristic of Cooksonia caledonica (compare figures 2.1B and 2.3A) (Morel et al. 1995). Poorly preserved spores place a maximum Gorstian age on the plant horizons. Toro et al. (1997) have described plant debris from the same formation further north at Cochabamba, comprising unbranched axes and Hostinella associated with Rhynia sp., Cooksonia sp., Zosterophyllum sp., and Drepanophycus sp., although examination of their illustrations suggests that at least some of their identifications fall into the “optimistic category” of Edwards (1990). The fossils are highly fragmented, partially coalified, and associated with graptolites indicative of a Late Wenlock—Early Ludlow age.

3. Ludlow, Shropshire, England (Jeram et al. 1990)

Historically, this is an important locality in that it contains the Ludlow Bone Bed, once thought to mark the Silurian—Devonian boundary, but now approximately equivalent to the Ludlow—Prídolí boundary. Excavations to make the bank safe yielded fresh rock just above the bone bed, which on maceration produced at least three new rhyniophytoid genera (e.g., figure 2.2A) and smooth sterile axes with stomata, the earliest yet demonstrated (Jeram et al. 1990), and numerous discoidal and fusiform spore masses (figure 2.4E,J,L), containing the dispersed hilate monads Laevolancis divellomedia s.l. (Wellman, Edwards, and Axe 1998b). The locality has also yielded the earliest body fossil evidence for trigonotarbids and various myriapods (see chapter 3).

4. Parana Basin, Brazil (Mussa et al. 1996)

Assemblages from two localities in the upper part of the Furnas Formation, dated by spores either as latest Silurian or Early Lochkovian, are currently being reinvestigated by Philippe Gerrienne (1999). Abundant coalified remains are dominated by naked, sometimes isotomously branching axes terminated by sporangia of Cooksonia pertoni morphology. Also recorded are a new species of Sporogonites, in which longitudinally striated sporangia are covered by minute spines; cf. Cooksonia cambrensis; Pertonella sp.; Salopella sp.; and axes with possibly microphyllous emergences or spines. The sporangia lack any spores that are considered critical for the identification of these taxa to specific or even generic level.

Figure 2.1.

Coalified Silurian fossils (except for the impression of Baragwanathia). A: Cooksonia cambrensis. Freshwater East, Wales. Prídolí. NMW77.6G.21. Scale bar = 1 mm. B: Cooksonia cf. caledonica. Tarija, Bolivia. LPPB 12744. ?Ludlow/Prídolí. Scale bar = 1 mm. C: Baragwanathia longifolia. Victoria, Australia. Ludlow. Scale bar = 10 mm. D: Salopella sp. Wulff Land, Greenland. Ludlow. MGUH. 17464 from GGU 319207. Scale bar = 1 mm. E: Cooksonella sphaerica/Junggaria spinosa. North Xinjiang, China. Prídolí. D4. Scale bar = 10 mm. F: Cooksonia pertoni. Hereford, England. Prídolí. NMW90.41G.1. Scale bar = 1 mm.

5. Xinjiang Province, northwest China (Cai et al. 1993)

The Wutubulake Formation has been dated as Prídolí, based on graptolites, and was probably deposited on one of the Kazakhstan plates, thus explaining similarities in the plants with those from the Balkhash area in Kazakhstan (Senkevich 1975, 1986). Cai et al. (1993) presented detailed descriptions of Junggaria spinosa Senkevich. The most complete specimens show pseudomonopodial branching with sporangia characterized by a broad margin terminating lateral dichotomously branching structures (figure 2.1E). Variation in the degree of lobing of the margin may indicate the presence of two species. Sterile axes at the locality show isotomous, pseudomonopodial, and more complex H-type, K-type, or clustered branching. Many bear a longitudinal central line, hairs, and small spines. Of particular interest is a single axis covered by crowded linear emergences up to 3 mm long with slightly swollen bases. It resembles a microphyllous lycopod, but there is no anatomical evidence to support such an affinity. Similar remains of approximately the same age have been assigned to Protosawdonia (Ishchenko 1975, in Podolia), Lycopodolica (Ishchenko 1975), or even Baragwanathia (Senkevich 1975; Cuerda et al. 1987). They demonstrate vegetative complexity in Silurian plants but in the absence of anatomical and reproductive information it is unwise to assume this is at a lycophyte grade. The ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Embryophytes on Land: The Ordovician to Lochkovian (Lower Devonian) Record

- 3. Rustling in the Undergrowth: Animals in Early Terrestrial Ecosystems

- 4. New Data on Nothia aphylla Lyon 1964 ex El-Saadawy et Lacey 1979, a Poorly Known Plant from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert

- 5. Morphology of Above- and Below-Ground Structures in Early Devonian (Pragian–Emsian) Plants

- 6. The Posongchong Floral Assemblages of Southeastern Yunnan, China—Diversity and Disparity in Early Devonian Plant Assemblages

- 7. The Middle Devonian Flora Revisited

- 8. The Origin, Morphology, and Ecophysiology of Early Embryophytes: Neontological and Paleontological Perspectives

- 9. Biological Roles for Phenolic Compounds in the Evolution of Early Land Plants

- 10. The Effect of the Rise of Land Plants on Atmospheric CO2 During the Paleozoic

- 11. Early Terrestrial Plant Environments: An Example from the Emsian of Gaspé, Canada

- 12. Effects of the Middle to Late Devonian Spread of Vascular Land Plants on Weathering Regimes, Marine Biotas, and Global Climate

- 13. Diversification of Siluro-Devonian Plant Traces in Paleosols and Influence on Estimates of Paleoatmospheric CO2 Levels

- References

- Index