eBook - ePub

Water–Energy Nexus in the People's Republic of China and Emerging Issues

This is a test

- 92 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Water–Energy Nexus in the People's Republic of China and Emerging Issues

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Water and energy are both valuable resources and indispensable for human society and economic development. By nature, water and energy are interlinked. Water plays a critical role in the generation of electricity for cooling of thermal power plants and in hydropower, as well as in the production of fossil fuels such as coal; energy is required to treat, distribute, and for wastewater treatment. Choices made in either of the sectors may have unintended and often negative implications on the other sector. This report analyzes the trade-off between the two sectors in the context of the People's republic of China and proposes recommendations to ensure that the choices made are sustainable in the long run.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Water–Energy Nexus in the People's Republic of China and Emerging Issues by Pradeep Perera, Lijin Zhong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Gestión medioambiental. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Gestión medioambientalChapter 1

Introduction

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has achieved remarkable economic growth since initiating market reforms in 1979. Gross domestic product (GDP) has grown by an average of 9.8% a year in the last 3 decades1—a record for a major economy—and per capita GDP in 2015 was roughly $8,016. Rapid and sustained economic growth has lifted more than 600 million people out of poverty, and enabled this upper middle-income country to achieve the Millennium Development Goals ahead of schedule.

This historic transformation of the economy has been accompanied by rapid urbanization, the largest movement of people from the countryside to the cities in history, and a structural shift toward industrialization. At the start of economic reforms 30 years ago, 80% of the population lived in the rural areas and agriculture accounted for about 35% of GDP. The PRC’s urbanization rate is 56.1%, and agriculture contributed 9.0% of GDP in 2015. The country has industrialized swiftly, in support of the export-oriented economic strategy it adopted in 1980. Although industry has recently had a decreasing share in overall GDP, its 40.5% in 2015 was still significantly higher than that of other major economies.

But rapid industrialization is exerting ever-growing stress on the country’s natural resources, including water and energy. Environmental issues associated with its industry-led, export-driven, and energy-intensive economic growth strategy and fast-paced urbanization demand solutions. The population, increasingly affluent and urbanizing, is pushing for secure and clean water sources, and the agriculture sector must meet the escalating need for food. Agriculture accounted for 63.5% of water withdrawals in 2014; the industry sector, including the energy sector, for 22.2%; and the residential sector, including urban water supply, for 12.6% (2014).

Energy takes different forms—electricity, heat, and petroleum, among them—and can be produced in several ways, each with a distinct requirement for water resources and impact on those resources. While the implications for water resources will generally increase as energy demand grows, the energy mix and the energy conversion technologies used will significantly affect water withdrawal and water consumption in the energy sector. Water is an essential resource for producing adequate quantities of energy. Water is used to extract fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas; to irrigate biofuel feedstock crops; to wash coal to remove unwanted minerals; and to refine crude oil into petroleum. In electricity generation, water is also required to cool most thermal power plants that depend on fossil fuels and nuclear energy, and it powers the hydroelectric and steam turbines (Q. Ying et al., 2015).

Given the energy-intensive nature of the PRC’s industry-led economic growth, the energy sector is a major water user. In 2014, the sector accounted for about 60, billion cubic meters (bcm), 10% of total withdrawals (International Energy Agency, 2014). Although most of the water that is withdrawn is returned to natural water bodies,2 the timing and location of release in the case of hydropower, and the quality in the case of thermal power and coal mining and processing, may have been significantly altered. As a result, other water users may have been permanently or temporarily prevented from using the water withdrawn by energy sector entities. The water consumption of the energy sector—withdrawn water that has been transformed into a different substance, evaporated, or polluted to the extent that it is not suitable for reuse—is estimated at 10 bcm.

Water and energy are both valuable resources and indispensable for human society and economic development. By nature, water and energy are interlinked. Water plays a critical role in the generation of electricity and the production of fuels, such as cooling power plants; energy is required to treat, distribute, and heat water. The availability and quality of freshwater to meet human needs have emerged as top-tier global issues for the environment and development (World Economic Forum [WEF], 2013).

Maintaining economic growth is imperative for the PRC, but it must proceed at a pace that is more moderate and sustainable. In view of the growth momentum of the PRC’s economy, even with significant improvement in energy and water use efficiency, the demand for energy and water is likely to increase further in the next 25–30 years. Choices made in either the energy or the water sector will have significant, multifaceted, and broad impact on the other sector, often with both positive and negative repercussions. This trade-off between energy and water resources is referred to as the water–energy nexus. (World Water Assessment Program [WWAP], 2014).

To address the increasing stress on the country’s resources and facilitate sustainable development, the government must understand the water–energy nexus, including the impact of energy development on water resources and vice versa, and improve its energy development strategies and water management practices. Regulatory and operational innovation toward integrated water–energy resources management is also a critical need.

Water Scarcity and Water Stress

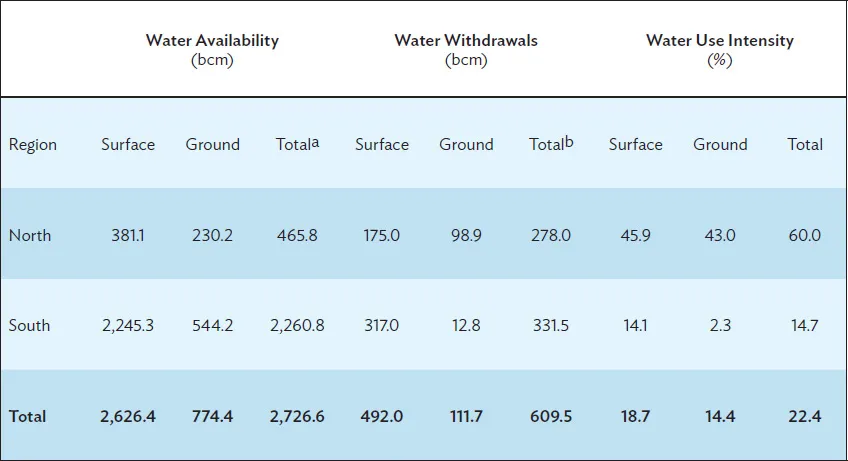

The PRC’s freshwater resource endowment, at 2.8 million m3, is the sixth largest in the world. However, its water resources are declining and unevenly distributed, both spatially and temporally, because of differences in topography and climate. Southern PRC is largely abundant in water resources; northern PRC, on the other hand, has only about 20% of the PRC’s water resources (Table 1).

Table 1: Water Resource Distribution Between the Northern and Southern Regions of the People’s Republic of China, 2014

bcm = billion cubic meter

a Surface water and groundwater are interrelated, and the total amount of water available is less than the sum of surface water and groundwater.

b The total water withdrawn includes surface water, groundwater, and a small portion of water from other water sources (e.g., reclaimed wastewater and harvested rainwater).

Sources: Water availability and water withdrawal data are from the Ministry of Water Resources, 2015; and water use intensity data are the author’s estimates. (See Box 1 for definitions of these terms.).

Per capita freshwater availability of about 2,100 m3 per year is just above the threshold considered adequate by the United Nations Environment Programme.3 However, most parts of northern PRC have an average per capita water availability of less than 700 m3 and are therefore considered “water scarce.” Northern PRC has 60% of the country’s farmland and 40% of its population, but only 20% of its water resources (L. Xi, L. Jie, and Z. Chunmiao, 2016). Per capita water availability in the Hai River Basin, where Beijing and Tianjin municipalities are located, is only 350 m3. Average rainfall in four river basins is down by 17%. Moreover, groundwater abstraction exceeds sustainable levels and groundwater levels are falling. On average, annual water shortages across the country amount to more than 50 bcm and two-thirds of the cities endure water shortages to varying degrees.

Freshwater withdrawals in the PRC in 2014 for residential, industrial, and commercial use amounted to about 164.5 bcm, excluding the water requirement for agriculture (386.9 bcm), for the cooling of power plants (47.8 bcm), and for ecological system (10.3 bcm). Water used in the residential, industrial, and commercial sectors usually comes from public water utilities, and is treated before reaching the end users. A significant share of the water supplied to these sectors (64.2 bcm) is consumed, and about 71.1 bcm is discharged into natural bodies of water after use. Wastewater also needs to be treated before it is released. In the PRC, about 80% of residential and industrial wastewater that is discharged into natural water bodies (55 bcm) is treated. But water used in nonpoint sources, such as agriculture, is not treated before discharge, and this is a major cause of surface water and groundwater pollution.

Box 1: Definition of Terms

There is a certain degree of confusion regarding the terms used to describe and quantify water used in industrial processes, including energy production. This confusion is mainly due to the lack of clarity regarding the exact definition of water withdrawal, water consumption, and water use.

Water withdrawal. The amount of water extracted from surface or groundwater. Most of the water withdrawn is usually returned to the water source or a natural water body, but the returned water may have an altered quality or temperature.

Water consumption. The amount of withdrawn water that is not returned to the natural water body from which it was withdrawn because of evaporation, transfer to a different water body, or transpiration. Water consumption, by definition, is less than water withdrawal.

Water use. This nontechnical term usually describes water utilization in different industrial processes and does not distinguish between the water used in one process and its reuse in another process. As a result, the amount of water used can be several times larger than the amount of water withdrawn and the amount of water consumed.

Water stress. The ratio of total water withdrawn to available freshwater in a river basin or catchment. Water stress is categorized as low (<10%), low to medium (10%–20%), medium to high (20%–40%), high (40%–80%), or extremely high (80%–100%). It can also be over 100% when the water withdrawal exceeds the water available on a sustainable basis from underground aquifers.

Source: William and Simons (2013). www.bp.com.

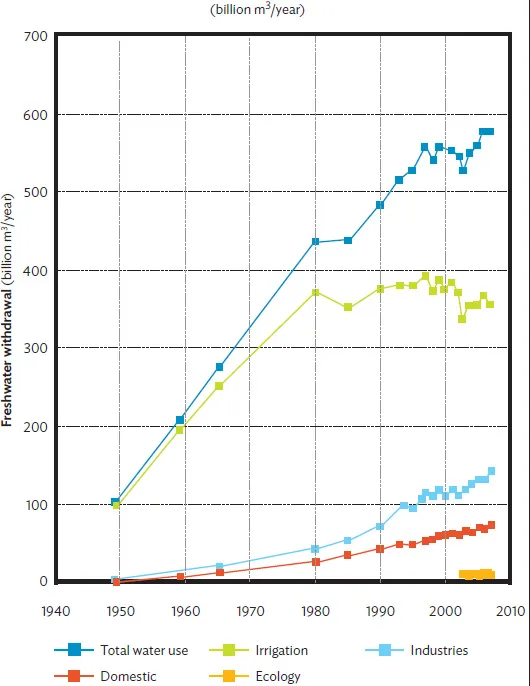

Although the growth in water withdrawals is driven by the residential and industrial (including energy) sectors, agriculture remains the dominant water user, with over 60% of total water withdrawals, compared with 28% for industry and 10% for the domestic sector (Figure 1). In 2014, freshwater withdrawals in the PRC declined for the first time in years, to 609 bcm, but this total was still 10% higher than water withdrawals in 2000. In addition, about 71 bcm of seawater was used to cool power plants in 2014. Freshwater use in the energy sector (excluding use in hydropower generation) is estimated to range from 50 bcm to 60 bcm per year, or about 10% of freshwater withdrawals in the PRC. About 50% of freshwater withdrawals are discharged into surface water bodies or groundwater aquifers, while the rest is consumed or evaporated.

Figure 1: Freshwater Withdrawals in the PRC, by Sector, 1950–2010

m3 = cubic meter.

Source: Global Water Partnership, 2015.

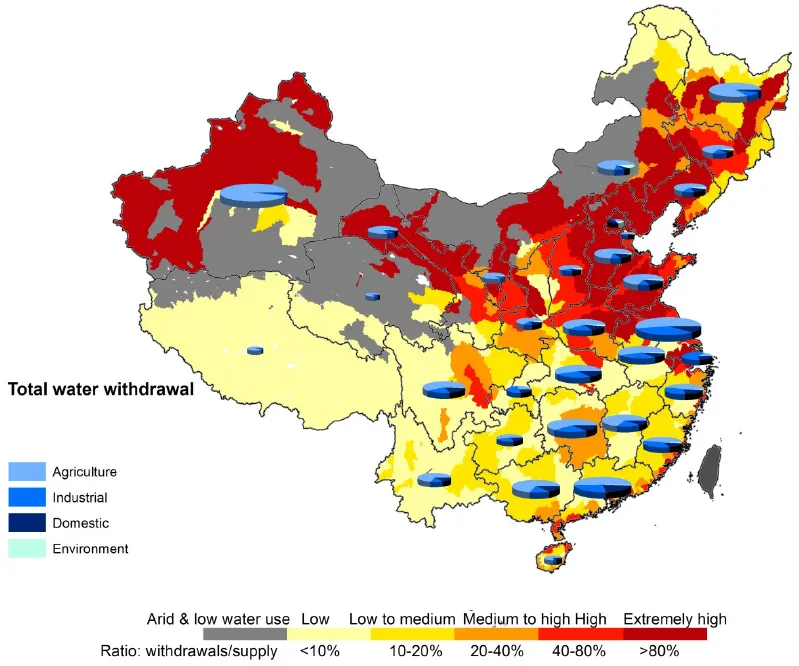

Climate change is another factor that accentuates the uneven distribution of water resources. Changing rain patterns, droughts, and extreme weather phenomena have an effect on both the availability and the geographic distribution of water resources (Figure 2). Precipitation is declining in both northern and southern PRC, but the more pronounced impact in northern PRC is undermining the capacity of water bodies in the region to fulfill their ecological functions. Some rivers in northern PRC are unable to maintain even minimum environmental and ecological flows (M. Oppenheimer et al., 2014).

Figure 2: Baseline Water Stress and Provincial Water Withdrawals in the PRC, by Sector, 2012

Sources: Water withdrawal data referred to provincial water resources bulletins issued by the provincial water resources management agencies; and the World Resources Institute’s Baseline Water Stress China Map (Wang, et al., 2016).

The heavily populated and industrialized northeastern region and the north–central and northwest provinces (IMAR, Shaanxi, and XUAR) suffer from severe water stress. Apart from water-intensive agriculture, industrial activities in provinces like Hebei, Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Shandong, and Tianjin, and increasing residential water use in urban centers such as Beijing and Tianjin, are contributing to the water stress. Climate change is expected to alter the rainfall and may intensify aridity in northern PRC, making both groundwater and surface water even scarcer.

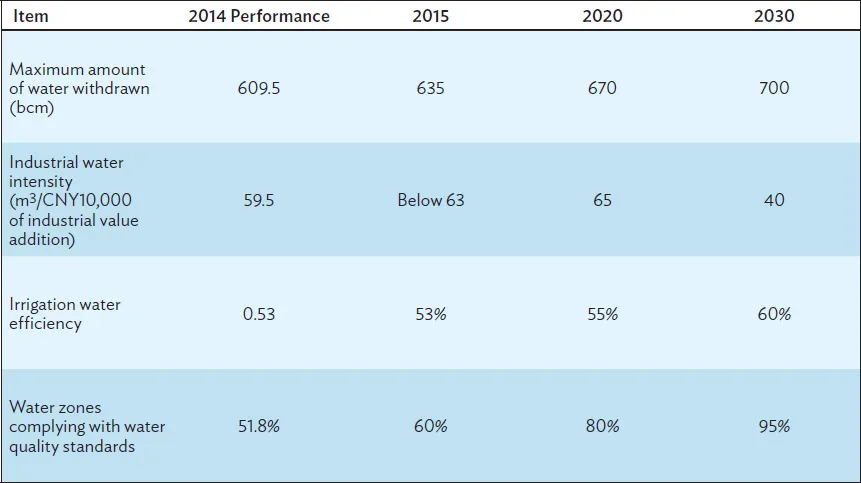

The PRC needs more water for continued economic growth, yet it is less efficient in its water use than more advanced countries. In 2013, the government set targets (Table 2) for controlling water withdrawals and improving water use efficiency in agriculture and industry (the “Three Red Lines”—reduce, increase, and protect). It singled out water use efficiency in the industry sector, including energy, as a key variable to be monitored. The planning guidelines need to be translated into policies, regulations, and standards to improve water efficiency. However, as water resource allocation and management reform lags behind other sectors, the conflict between maintaining the momentum of economic growth and promoting sustainable water use must be resolved through market-based mechanisms (Y. Jiang, 2009).

Table 2: Water Planning Guidelines

bcm = billion cubic meter, m3 = cubic meter.

Source: Qin et al., 2016.

The government intends to ensure compliance with its water use guidelines by establishing a water allocation plan and water use quotas for water withdrawal from rivers, lakes, and groundwater aquifers. These quotas will form the basis for water licensing decisions and will be set at river basin level, as well as at the level of administrative units (provinces, prefectures, and counties). New applications for water withdrawal will be approved on the basis of water availability, water use efficiency, extent of water pollution control, potential for water saving, and water rights transfer. Applications that exceed the water use quota for the river basin or the administrative unit will not be approved.

The industrial water intensity standard will apply to the thermal power generation, oil refining, iron and steel, textile, paper, chemical, and food processing industries. Compliance with the standards for industrial water use and irrigation water use efficiency will be monitored through self-reporting and routine inspections by provincial units of the MWR. Water quality will be measured within water function zones of major rivers and lakes designated as such by the MWR. These will consist of major rivers and their tributaries with a catchment area of more than 1,000 square kilometers (km2), lakes and reservoirs of national importance, and protected water bodies of national significance.

Overview of the Energy Sector in the PRC

The PRC is the world’s largest energy consumer, with an energy sector heavily dominated by coal. The country is the world’s largest producer and consumer of coal. In 2014, it consumed 3.87 billion tons of coal—about half of global coal consumption—and relied on coal for 66% of its primary energy supply and over 70% of its electricity supply. The reduction of coal consumption continued to 3.75 billion tons in 2015. However, there has been a gradual and steady decline in the share of coal in the PRC’s energy consumption, from 7...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures, Tables, and Boxes

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Water Use in Coal Industry

- Chapter 3 Water Use in the Oil and Gas Sector

- Chapter 4 Water Use in Electricity Generation

- Chapter 5 Water Use Implications of Hydropower

- Chapter 6 Energy for Water

- Chapter 7 Conclusion

- References

- Footnotes

- Back Cover