THE WAITING ROOM

Joe sat on the bench in the waiting room. Looking down, he noticed that the bench was screwed to the floor. Not even the furniture here was free. Perspex screens and locked doors separated him and the others waiting from those for whom they waited; the veils between the untrustworthy and those to whom they were entrusted. Joe absent-mindedly read the graffiti carved into the bench; testimonies of resistance that made the place feel even more desperate.

Joe scanned the postered walls, shouting their messages in pastel shades and bold print. Problems with drugs? Problems with alcohol? Problems with anger? Stay calm. Apparently, help was at hand – or at the end of a phone-line. But meanwhile remember that abusive language and aggressive behaviour will not be tolerated. Not in this room that itself felt like an installation of abuse and aggression. To Joe, it said ‘You are pathetic, desperate or dangerous. You are not to be trusted. You must wait’.

He fidgeted and returned his eyes to the floor, downcast by the weight of the room’s assault, avoiding contact, avoiding hassle, staying as unknown as possible in this shame pit. Better to be out of place here than to belong. This was no place to make connections.

Joe wondered what she would be like – Pauline – the unknown woman who now held the keys to his freedom. Her word had become his law: This was an ‘order’ after all. He was to be the rule-keeper, she the ruler – cruel, capricious or kind. She might hold the leash lightly or she might drag him to heel. Instinctively, he lifted his hand to his neck, but no one can loosen an invisible collar. At least it was not a noose. Joe swallowed uncomfortably, noticing the dryness of his mouth and the churning in his gut. He was not condemned to hang. He was condemned to be left hanging.

Joe wondered what Pauline would be like.

PERVASIVE PUNISHMENT?

Pervading, adj.: That pervades; that passes or spreads through.

Pervasive, adj.: Having the quality or power of pervading; penetrative, permeative, ubiquitous. (Oxford English Dictionary)

The opening episode printed in italics at the beginning of this chapter – like similar passages at the start of each chapter in this book – forms part of a short story. That story is a work of creative, imaginative writing but it is a fiction that, like the italic font in which it is presented, leans on research and practical experience of criminal justice supervision, both others’ and my own – the same research and experience that forms the basis for the more conventional academic analyses that constitute each chapter of this book.

The purpose of the short story is to imaginatively bring to life the themes and content of this book. Ideally, I want you, the reader, to become curious about Joe and to care about what is happening to him and to the other characters we will meet in other episodes. I hope that by helping us to imagine how it feels to be supervised, and to be the supervisor, this fiction will help us to become curious and to care about the entirely real but largely hidden and neglected forms of suffering and support that this book aims to expose and explore. These are forms of suffering and support that affect millions of people around the world every day and that are imposed, at least in theory, on ‘our’ behalf, for the collective good. It follows that we all have a duty to imagine, examine and enquire about them carefully, and to consider whether we are content with these forms of pervasive punishment.

That title – Pervasive Punishment – perhaps already hints at the difficulty in delimiting such a project. This book concerns a diverse set of institutions and practices about which it is impossible to agree a common or settled language; institutions and practices that have evolved differently in different places. At least some of these definitional complexities will be unravelled later (mainly in Chapter 4). For now, the Anglophone terms ‘probation’ and ‘parole’ serve as useful starting points; suffice is to say that our focus here is on sanctions or measures imposed by criminal courts that involve some form of supervision in the community, whether instead of a custodial sentence (as in certain forms of suspended or conditional sentences), as a community-based sentence in its own right (like probation, in some jurisdictions), or as part of a sentence that begins with imprisonment but extends beyond it (as in parole). When US-based scholars write and talk about populations under ‘correctional supervision’, they sometimes mean both people in prison or jail and people on probation or parole. Here, I will use the term ‘supervision’ in the more limited European way, to refer only to those under some form of penal supervision in the community.

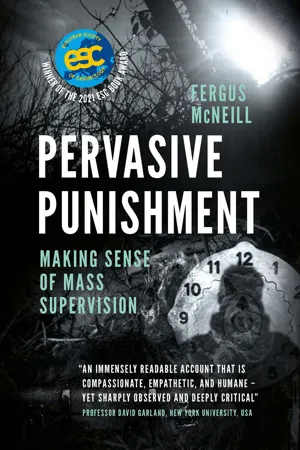

The title Pervasive Punishment is borrowed from a book chapter that I co-authored with Wendy Fitzgibbon and Christine Graebsch. That chapter explored how people chose to represent their experiences of supervision in and through photographs, as part of a project called ‘Supervisible’,1 which will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 (Fitzgibbon, Graebsch, & McNeill, 2017). I will use images from that project and from its sister project ‘Picturing Probation’ (see Worrall, Carr, & Robinson, 2017) throughout the book to illustrate the short story; for example, the picture in Figure 1 is taken from the Picturing Probation project.2

Fitzgibbon et al. (2017) concluded their chapter by arguing that:

[…] much of the Anglophone literature on probation practice (and on experiences of supervision) focuses on probation (or supervisory) meetings. The implicit assumption in these studies is that it is in these human encounters that supervision ‘happens’. Our findings suggest that the experience of supervision is a much more diffuse and pervasive one; for our supervisees at least, it seems to extend in time and in impact across the life of the supervisee.

Equally importantly, this pervasive impact of supervision is experienced as being painful. Looking across the common themes above, we might argue that this pain consists largely in the combination of being (continually) judged and constrained over time, and in the presence of a suspended threat. (Fitzgibbon et al., 2017, p. 318)

In other words, we argued that the effects of supervision are often diffuse – they pervade the lives of supervisees – and that, even when experienced as helpful, they hurt. By way of illustration, one Scottish participant in the Supervisible project engaged the help of a friend in taking the picture shown in Figure 2. In it, cast as shadows, they dangle from a climbing frame in a children’s play-park. Another Scottish participant, interpreting this picture, told me that it reminded him of a spider’s web. He saw the two shadows as supervisor and supervised, one elevated and one degraded, both trapped in the justice system: ‘the more you struggle, the more tightly it binds you’. However, unlike imprisonment (and here the spider’s web metaphor breaks down), supervision seeks to bind not by confining the supervisee to a place, but rather by moving with him or her. It is, in this sense, an ambulant or mobile punishment (Morgenstern, 2015).

The term ‘pervasive’ in the book’s title also alludes to another sort of penal mobility. It is not just that supervision permeates the lives of individual supervisees; it has also spread through society itself – and even across societies. Indeed, as we will see in Chapter 3, in some places and for some segments of the population, supervision is becoming commonplace, if not quite ubiquitous.

As many readers will immediately recognise, this is far from being a novel observation. Several decades ago, Andrew Scull (1977, 1983), Thomas Mathieson (1983) Stanley Cohen (1983,1985) and others warned of the ‘dispersal of discipline’ beyond the prison. Cohen’s (1985) highly influential book Visions of Social Control warned that a policy rhetoric of diversion and decarceration was cloaking the emergence of more expansive and penetrating forms of ‘deviance control’. He argued that these new forms were serving to widen the penal net at the same time as thinning its mesh, dredging more people into rather than fishing more people out of the penal system. For both Cohen and Scull, the growth of ‘community corrections’ (meaning probation and parole systems and other forms of ‘intermediate punishments’) was an important part of this alarming picture.

Gwen Robinson (2016) has recently reminded us that these sorts of analyses had crystallised by the late 1980s to such an extent that Lowman, Menzies and Palys (1987) produced an edited collection on Transcarceration. Rather than accepting the logic of probation, parole and other measures as alternatives to imprisonment, the concept of transcarceration stressed the connections and conjunctions between different sorts of penal institutions and measures, suggesting a symbiotic rather than a substitutionary relationship between imprisonment and its supposed community-based ‘alternatives’. As Robinson observes, the editors of the collection also stressed that transcarceration involves:

the marriage of exclusive and inclusive modes of social control, as evident in the emergence in some jurisdictions of home confinement schemes (Blomberg, 1987) and the expansion of parole and other mandatory forms of post-custodial supervision (Ratner, 1987). (Robinson, 2016, p. 100)

However, Robinson (2016) goes on to argue that, during the 1990s and 2000s, rather than continuing to develop, test and refine these sorts of analyses, scholars became preoccupied instead with the advent of mass incarceration (Garland, 2001). In consequence, she suggests that what little sociological interest there has been in supervision has tended to focus on those forms of supervision that are most closely related to imprisonment, that is, parole and electronic monitoring. Other community-based sanctions and measures (like probation or community service) have been even more neglected. This leads Robinson to characterise community sanctions and measures as the ‘Cinderella’ of ‘Punishment and Society’ studies, leaving it as:

[…] a neglected and under-theorised zone – despite the fact that, as we have seen, several scholars in the 1980s foresaw the expansion and diversification of forms of non-carceral control in many Western jurisdictions, and the empirical reality that offenders subject to some sort of supervisory sanction in the community have, in many jurisdictions, come to substantially outnumber those subject to custodial confinement. (Robinson, 2016, p. 101)

In writing Pervasive Punishment, one of my main hopes is to help Cinderella come to the ‘Punishment and Society’ Ball.

PERVASIVE PUNISHMENT

Robinson (2016) offers three reasons for the neglect of supervision since the 1980s: problems of definition, language and labelling; the relative (in)visibility of the field; and the debatable penal character of community sanctions – that is, ‘the question of whether such sanctions are in fact instances of punishment at all’ (p. 105).

In a formal or legal sense, this is a fair question – and one that, as we will see in Chapter 4, has different answers in different times and places. I have argued before (McNeill, 2013) that probation and parole emerged in many jurisdictions, particularly in Anglophone countries, as something to be done instead of punishment or, primarily in countries with Roman law traditions, as a form of suspended punishment or as something that follows on after punishment to mitigate its adverse consequences by promoting reintegration (Herzog-Evans, 2015; Morgenstern, 2015).

This peculiar status of supervisory sanctions and measures – as something defined by what they are not – may have suited penal reformers trying to divert people from the demoralising dangers of imprisonment and into nascent forms of social welfare (Garland, 1985). However, its current-day legacy is a profound problem of legitimacy for supervision. Rightly or wrongly, supervision has come to be seen, at least in some jurisdictions, as being a service rather than sanction, and one mainly concerned with the interests and needs of ‘offenders’. The logic of diverting troubled people from punishment to help may have appealed to the sensibilities of some of our nineteenth- and twentieth-century forebears. However, as many have argued, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, ‘welfarism’ came to be displaced by ‘populist punitiveness’ (Bottoms, 1995). This shift in sensibilities conspired to produce a shrinking conceptual space for supervision as an alternative to punishment and demand its re-legitimation precisely as a form of punishment that also offers protection from certain risks and, crucially, does so at less cost than imprisonment (see Robinson, McNeill, & Maruna, 2013).

I will return to these legitimacy-related late-modern re-framings of supervision (and of punishment more generally) in Chapters 4 and 6. But there is a second problem posed by the origins of supervision as diversion from punishment (see McNeill, 2013; Sparks & McNeill, 2009); a problem that may partly explain the slower progress of human or civil rights discourses in relation to supervision rather than imprisonment. The difficulty rests in the historical roots of community sanctions in many jurisdictions as acts of clemency or mercy. Recipients of clemency or mercy are not diverted from or excused punishment because they deserve such treatment; rather, they are diverted because the state elects not to proceed with the measures of punishment to which it is nonetheless entitled. As philosophers of punishment have pointed out, part of the point of mercy is that it is undeserved (Murphy 1988; Smart 1969; Walker 1991). For that reason, mercy is not something to which someone can usually extend a rights-based claim.

Even though supervisory sanctions are now often located within a range of penalties with varying degrees of severity, and whether or not this ‘tariff’ is formalised in law, the public (and sometimes professional) perception remains that the ordering of such a sanction is an act of judicial or executive largesse rather than a determination of justice. When this perception is combined with the public suspicion that such largesse is tied to some aspect of the case that they deem to be of questionable relevance, public cynicism may be the result.

A recent example from England illustrates this point. It concerns the controversy around the sentencing of a 24-year-old woman named Lavinia Woodward, found guilty of ‘unlawful wounding’. She had stabbed her then boyfriend in the leg while under the influence of drugs and alcohol. On 26 September 2017, the Daily Telegraph (a conservative newspaper, but not a tabloid) reported, on the sentence in the following terms:

An Oxford medical student ‘too bright’ to be given a prison sentence has been allowed to walk free from court – despite the judge acknowledging that she broke her bail conditions […] Lavinia Woodward […] was spared jail yesterday as she was commended for her ‘strong and unwavering determination’ to address her drug addiction […] It comes four months after Judge Ian Pringle QC described Woodward, an aspiring heart surgeon, as an ‘extraordinarily able young lady’ whose talents meant that a prison sentence would be ‘too severe’ (emphases added).

Despite the terms of the report, the Judge had in fact imposed a 10-month jail sentence, suspended for 18 months under a Suspended Sentence Order (SSO). The newspaper fails to report the conditions of the suspension; that is, what Woodward needs to do and not do for the next 18 months to avoid the implementation of a 10-month jail sentence.3

Setting aside important and reasonable questions about the fairness and appropriateness of this sentence – and the potential role of privilege in the process – for present purposes, the important point is this: in many of the press reports of this case, the sentence itself is misunderstood and misreported in such a way that its meaning and effects are misrepresented. Woodward was not ‘spared jail’ and she has certainly not ‘walked free’ from the court. She was s...