![]()

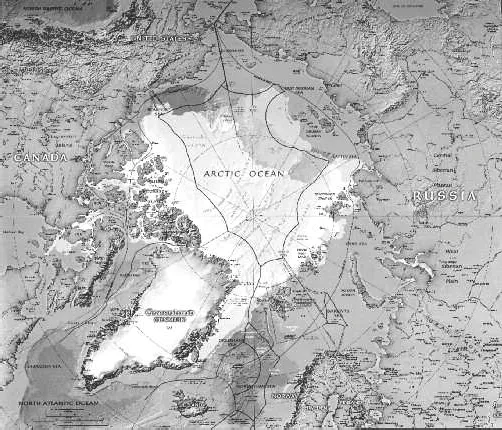

Circumpolar view of the Arctic.

1

Origins: Introduction and Environmental Overview

In July 1895, after months of allowing his research vessel, the Fram, to drift through the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean, Fridtjof Nansen of Norway caught sight of land for the first time in almost two years. Finally, he exclaimed, ‘we again see something rising above that never-ending white line on the horizon yonder – a white line which for countless ages has stretched over this lonely sea, and which for millennia to come shall stretch in the same way.’ For the crew of the Fram, to be where the human eye could once more perceive topographical difference was to recover the human sense of passing time, an experience Nansen likened to starting ‘a new life’. ‘For the ice’, by contrast, every moment was, and ever would be, ‘the same’.1

Throughout recorded history, wilderness in many forms has served to symbolize elemental vastness and permanence. The forest primeval. The earth-rooted mountain. Boundless steppes and limitless seas. That said, perhaps no landscape has stood out in the modern mind as so quintessentially timeless as the Arctic. In the Western imagination, the polar world has featured as a realm of crystalline purity, as a grey kingdom of frozen death, and in other guises besides, but is most often seen as eternal and unchanging. Nansen described it further as ‘so awfully still, with the silence that shall one day reign, when the earth again becomes desolate and empty’ – making him merely one of dozens who essentialize the Arctic, even if just for poetic effect, as an ageless expanse marked solely by the inexorable encroachment of glaciers upon the land, the mesmerizing shimmer of the aurora borealis, and endless cycles of migration leading polar bears, reindeer and whales in never-varying circles over the earth and through the ocean depths.2

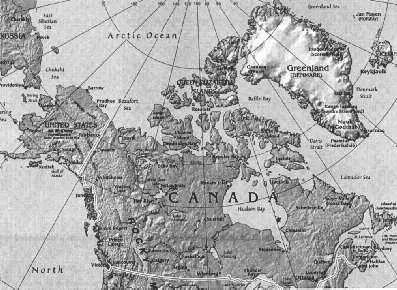

The North American Arctic and Greenland.

But the Arctic, of course, does change. Like all places, it moves through time, shaped by natural forces and human agency alike. Also, to those who live there or pay it close attention, it presents more faces than it is commonly thought to have. The American explorer Elisha Kent Kane cleaved to the standard view in his Grinnell expedition diaries, declaring the Arctic ‘a landscape such as Milton or Dante might imagine: inorganic, desolate, mysterious . . . unfinished by the hand of its Creator’ – whereas the Canadian naturalist Farley Mowat insists that ‘the Arctic is not only the ice-covered cap of the world’ or ‘the absolute cold of the pole’, but also ‘two million square miles of rolling plains that, during the heat of midsummer, are thronged with life and brilliant with the colors of countless plants in full bloom’.3

The purpose of this book is to portray these many visages and to trace the Arctic’s passage through time as fully as possible. Both tasks necessitate the weaving together of many narratives, for ‘Arctic history’ encompasses not just the oft-repeated chronicle of polar exploration, but processes of national development, economic organization and resource mobilization. It is the still-undervalued tale of the peoples indigenous to the Arctic and their frequently painful interactions with Euro-American outsiders and colonizers. It is bound up with the histories of science, technology, diplomacy and war. It demands an appreciation of the environment’s climatological and zoological complexities. No book of this length can pretend to cover any of these topics encyclopaedically, but it can aim for a global approach by emphasizing the interrelationships that exist among them. Above all, it will strive to be guided by the insight, voiced by the respected author Barry Lopez, that, in the North, ‘people’s desires and aspirations [are] as much a part of the land as the wind, the solitary animals, and the bright fields of stone and tundra’ – and that, at the same time, ‘the land itself exist[s] quite apart from these’.4 Both humanity and natural space are part of Arctic reality, and both will be as present as I can make them in this slim volume.

Siberia and the Eurasian Arctic.

Conventions

By rule-of-thumb reckoning, the Arctic consists of 11 million square miles of sea and solid land. Delimiting this territory, however, is no straightforward task, for there exists no generally agreed-upon definition for it. The region’s most distinct landmark, the North Pole, is not just invisible, but is in fact several poles. The Geographic North Pole, at 90°N – ‘the’ Pole in most people’s minds – has the most firmly fixed location, but even it wobbles from month to month in an erratic circle about 15 feet in radius, and the North Magnetic Pole, toward which the compass points, strays more widely still: 77°N 120°W in 1985, 81°N 111°W in 2001, and 83°N 114°W in 2005. Scientists have also mapped out a North Geomagnetic Pole and a Northern Pole of Relative Inaccessibility, the point farthest from any land mass.5

As for the Arctic Circle, or latitude 66°33′N, this is a cartographic abstraction that marks the southernmost point where polar day and polar night – 24 hours of uninterrupted light or darkness – occur in the northern hemisphere. Such a demarcation gives little sense of actual conditions on the ground, for certain areas enclosed by the Circle are surprisingly temperate, owing to peculiarities of wind, terrain or water, while many ‘subarctic’ zones are actually Arctic in their climate or ecology. For example, the second-coldest temperature known to modern science in the northern hemisphere was recorded in Oimyakon, in Russia’s Sakha Republic (formerly Yakutia), 200 miles south of the Arctic Circle, while Norway’s Lofoten Islands, at 68°N, but bathed by warm ocean currents, enjoy an average January temperature above 32°F. Other commonly suggested definitions – such as the northern treeline, the southern extent of iceberg drift or continuous permafrost, or the 50°F isotherm as recorded in midsummer – likewise fail to capture the region’s characteristics consistently and inclusively. Wildlife and weather systems are no respecters of lines drawn on maps, and neither, for most of their history, have aboriginal populations been. Certain regions lying below the Arctic Circle, including Iceland and the Faeroes, Newfoundland and Labrador, Kamchatka and the Aleutian Islands, have played important roles in Arctic history, whether as jumping-off points for the exploration or colonization of the Arctic, or because their inhabitants based substantial parts of their economic practices on the exploitation of Arctic resources. For ease of use and the sake of flexibility, this book will take as its subject the land and waters north of 60°N, granting itself leeway to veer to the south when the topic at hand calls for doing so. It will avoid excessive technicality and use the terms ‘north’, ‘far north’, or ‘high north’ interchangeably with ‘Arctic’; more restrictive designations, such as ‘circumpolar’, ‘high’ and ‘low’ Arctic – the line between which is customarily taken to be 75°N – and the names of specific places or subregions will be used where appropriate. The term ‘subarctic’ will refer to regions lying between the 55th and 65th parallels.

If geographical terminology requires discussion, so does that for the Arctic’s inhabitants, with many well-known labels having become less politically acceptable or less ethnographically precise, and with different countries observing different protocols. Herein, the terms ‘indigenous’, ‘native’ and ‘aboriginal’ are treated as synonymous and as suitably applicable to any region; if the word ‘primitive’ is used, it refers to levels of technological development and is not meant to carry the connotations it once did of savagery or inferiority. With respect to specific groups, this book will privilege the names favoured by the groups themselves, but also make clear how they used to be known, or how they are still known popularly. In other words, it will be evident that the Sami are the people once called ‘Lapps’, that the Nenets appear in old chronicles as ‘Samoyed’, and so on. The term ‘Indian’ will appear mostly in quoted material or direct context, and occasionally on its own when the preferred U.S. and Canadian labels, ‘Native American’ and ‘First Nations’, fit poorly into a given sentence. In Russia, the most common umbrella terms are ‘native Siberians’ and ‘small peoples of the North’ – ‘small’ referring to population count, not physical size – although many of the country’s northern aboriginals live west of Siberia or, like the Sakha (Yakut) and Komi, are too numerous to fall into the category of ‘small’. Here as elsewhere, particular groups will be called by their own names whenever feasible. As for the non-natives who came to the Arctic or claimed dominion over it, they will be identified, if not by specific nationality, as ‘European’, ‘Western’, ‘Euro-American’ or ‘white’.

The nomenclature presenting the most difficulty is ‘Eskimo’, which, like ‘Indian’, was applied by outsiders to people who have their own names for themselves and is rejected by some as derogatory, but none-theless remains acceptable in certain quarters. ‘Eskimo’ once served as the standard ethnonym for all Inuit and Yupik peoples who inhabit the territory stretching from eastern Siberia to Greenland and share a common ethnocultural heritage. (Linguistically related to both, the Aleuts of the Bering Sea are considered distinct and do not factor into this debate.) On the other hand, the word was borrowed by Europeans from Algonquin-speaking Native Americans – who, if the traditional etymology holds true, mocked their northern neighbours as ‘eaters of raw flesh’ – and many consider it offensive. Since the 1977 formation of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, and especially in Canada and Greenland, where the old usage is heavily stigmatized, the habit has been to revive indigenous names, with the term ‘Inuit’ most frequently employed as a collective label for the peoples once known as ‘Eskimo’. However, the former has not won the same breadth of acceptance as the latter used to enjoy. One complication arises from its dual nature: Inuit serves as a general category, but also refers specifically to certain natives in the Canadian Arctic – as distinct from other ‘Inuit’, such as central Canada’s Inuinnaq, the Inughuit of Greenland and Ellesmere Island or the Inuvialuit of Canada’s western territories. A second problem centres on Alaska, where many Inupiat of the North Slope resist being classified as Inuit, and where the term excludes the Yupik. In Alaska, ‘Eskimo’ holds more currency as a generic label, and it is used among Russia’s Yupik as well, although less readily than in the United States. Like many works on the subject, this book will follow the conventions laid out in the ‘Arctic’ volume of the Smithsonian Institution’s Handbook of North American Indians, which recommends using ‘Eskimo’ in the Alaskan case, ‘Inuit’ when referring to Canada or Greenland, and more precise designations wherever possible.6 In no case will the terms ‘Indian’, ‘Native American’ or ‘First Nations’ apply to Eskimo or Inuit, although the phrase ‘Alaskan native’ includes Eskimos, Aleuts and Native Americans.

Many languages are relevant to Arctic history, a number of which must be transliterated from non-Latin alphabets, and there is no one method of rendering foreign terms and names into English that perfectly balances consistency, academic rigour and readability. As a rule, I have favoured the last, choosing where I can the best-known and/or most visually pleasing version of a word borrowed from another tongue or orthography. Place names change over time and due to political circumstance; older names will be used in their proper context, but also identified with the newer toponyms that have replaced them. Dates are given according to the Western calendar, with distinctions between BCE (before common era) and, where necessary, CE (common era), rather than BC (‘before Christ’) and AD (anno Domini). Unless otherwise specified, all dates, including those in the sections on prehistory, are measured in calendar years rather than radiocarbon years.

The Ecosphere

In the beginning, during the volcano-charged Hadean and Archean eons (4.6 to 2.5 billion years ago), immense fountains of magma gouted upward into the northern sky. Then, for many millions of years, there was little but ocean, for it was largely in the south that the first land masses formed, broke apart and recombined into the early supercontinents. Tectonic forces periodically carried sizable fragments of land close to the Arctic Circle, but not until the cusp between the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic eras, or around 260 million years ago, did elements of what is today circumpolar territory drift into the North. The Arctic Ocean took its largely landlocked form around 50 million years ago, during the Eocene epoch, and it was at the beginning of the Pleistocene, nearly 2.6 million years ago, that the rest of the Arctic map came to look fundamentally as it does today.7

Only after 12,000 years ago, as the Younger Dryas, the last cold snap of the Pleistocene, came to an end, and as the great ice sheets receded from Eurasia and North America, did the Arctic’s present-day ecosystem take shape. Ironically, for all the perception by outsiders of the region as primordial and permanently formed, the Arctic environment is the world’s youngest; not long ago on the geological timescale, the flora, fauna and climate of the circumpolar north were startlingly different from anything imaginable today. Alaska’s North Slope and the ‘greensands’ of Canada’s Devon Island have yielded fossil evidence from 70 to 75 million years ago which indicates that, during the Cretaceous, tall trees stood in the Far North, while sinewy plesiosaurs and huge, primitive sharks patrolled the ocean depths. The north polar waters were virtually free of ice, and portions of upper Siberia, Alaska and the Canadian archipelago were carpeted with ferns, gingko, swamp cypress and dawn redwood (Metasequoia). As far north as 75 degrees – on land that would have drifted as high as 85°N during the Cretaceous – palaeontologists have uncovered the remains of such unexpected creatures as gliding lemurs, the hippopotamus-like Coryphodon, and a miscellany of dinosaur species, from the pint-sized therapod Troodon to the 4-ton, plant-eating Edmontosaurus and the Gorgosaurus, a fierce, 30-foot-long carnivore. Whether the Arctic at this stage was as temperate as the existence of such species would imply or whether the animals were better adapted than their modern descendants to cooler conditions, the region for a long time resembled the sort of fantasy adventureland more typically encountered in the pages of a Jules Verne or H. G. Wells novel.

All this changed with the advent of the Pleistocene, which repeatedly blanketed the northern hemisphere with enormous continental glaciers. Popularly but erroneously thought of as ‘the’ ice age, the Pleistocene was a time of successive glacial periods, each separated from the next by a warm interglacial phase, and with brief spells of gentler weather, called interstades, punctuating the glacial periods themselves. This cycle has not stopped: the Holocene epoch we live in now, far from having ended the ice age, is merely the latest interval in the long process of Quaternary glaciation – a blink of the eye in planetary terms before the inevitable return of the ice some thousands of years from now. (A sobering thought for those disposed to think about history on the grand scale, but given the pressures placed on the environment by civilization today, we will be lucky indeed to survive long enough for a new approach of the ice to be humanity’s terminal crisis.) The last ice age began around 100,000 years ago, spawning the glacial masses conventionally known in North America as the Wisconsin, comprised of the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets; the Devensian or Midlandian in the British Isles and Ireland; the Würm atop Europe’s Alps; and the Weichselian in Fennoscandia and European Russia, made up of the Scandinavian and Barents-Kara ice sheets. Siberia east of the Taimyr Peninsula, most climatologists believe, was left relatively unglaciated. More recently, scientists have come to use the marine isotope stage (MIS) as a preferred yardstick with which to measure the Quaternary period’s glacial and climatic fluctuations, with warm interglacials and interstadials represented by odd-numbered stages, and glacial advances by even-numbered stages.8 MIS 1 corresponds with the Holocene, MIS 4 with the early onset of the Wisconsin-Weichselian glaciation. Whatever label one gives them, the late-Pleistocene ice sheets reached their maximum extent between 22,000 and 18,000 years ago, and although they began their gradual retreat thereafter, this age of mastodons, sabre-toothed cats and woolly rhinoceroses persisted for several more millennia. As described in chapter Two, hominid presence had already made itself felt in the North, many times in the subarctic during interglacials and interstades, and increasingly in the Arctic during the late Upper Palaeolithic.

Except for the Greenland interior – where the 660,000-square-mile, berg-birthing ice cap preserves the character of the Pleistocene into our own day – the Arctic terrain left behind by the glaciers’ withdrawal ranges up from the northern edge of the taiga, or boreal forest, through the permafrosted shrublands and sedges of the tundra, and finally to the polar deserts of the extreme north. Commonly spoken of as ‘belts’, these biomes are in reality spread irregularly across the map. A sparser, more open type of woodland often sits between taiga and tundra, with the treeline meandering back and forth across the Arctic Circle, and occasionally past 70°N. Tundra, from the Finnish word for ‘treeless land’, is interspersed with mountains, river deltas, woods and coastlines, all...