![]()

PART ONE

The Myth of the Archetypal Image

![]()

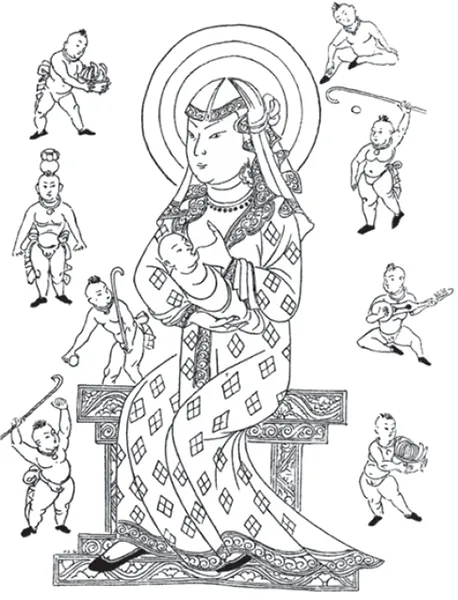

6 The Goddess Kuan-Yin, sketch of a painting on silk found at Yar-khoto, China, 10th century.

Lifetime Portraits in Asia

It was probably on present-day Sri Lanka that Marco Polo, on his way back to Venice in the 1280s, discovered some of the oldest traditions concerning the origins of the Śākyamuni Buddha’s image, with which he had become acquainted during his seventeen-year stay at the Mongolian court at Beijing. He and earlier travellers to Asia had regularly been struck by the ubiquity and number of Buddhist statues, by their often enormous dimensions (illus. 7), and by their striking similarity, in form and function, to Western Christian religious images. It was not difficult to mistake winged deities for angels, the bodhisattvas and pious arhats displaying the vitarka-mudrā gesture for blessing bishops, and colossal Buddhas (illus. 8) for monumental images of the giant St Christopher (illus. 9). Western visitors did not expect to find such widespread use of images to the east of the Islamic-ruled lands, which were perceived as a dreadful, almost endless aniconic desert. At first sight the presence of statues was interpreted as bearing indirect witness to the Christian affiliation of a ritual space: in his first thrilling and fortuitous visit to a Lamaist temple in Kajlak (present-day Kazakhstan), Friar William of Rubruck glanced at the statues displayed in the innermost room of the building and immediately assumed that he had entered a church owned by uncultivated Christians, like the famous Nestorians (or east Syrians) who were known to have established themselves in inner Asia.1

Yet it did not take Christian visitors much time to understand that these images were the expression of an autonomous and sophisticated religious tradition, which they characterized as marked by the special role played by the veneration of statues. In Marco Polo’s Milione the term ydres (‘idolaters’) stands plainly for Buddhists and other believers of the East, including Hindus, Taoists and Confucians. Nonetheless, seen in comparison with Islamic aniconism, the East Asian use of images seems to retain, in these writers’ perception, a relatively positive appreciation. This is made evident by a number of legends, like that narrated in the fourteenth century by the Florentine traveller and later Archbishop of Prague Giovanni de’ Marignolli, who maintained that the inhabitants of Kampsay (present-day Hang Chou) venerated an image of the Virgin Mary in one of their temples and honoured her with a triumph of light on the occasion of Candlemas (2 February). In fact, he had seen a statue of the goddess Kuan-Yin (illus. 6) – who was frequently represented as a mother with child – and had interpreted the fireworks of the Chinese New Year as a light show standing for the ritual candle procession of the Roman Catholic Church.2

| 7 Temple image of the goddess Kannon. Nara (Japan), Hasedera. |

Marco Polo formed a rather positive idea of the Enlightened, known to him as Sergamoni Borcan, an expression combining Śākyamuni’s name with a Mongolian word, borkhan, meaning ‘divinity’ and ‘image’. The Buddha’s secular name was indeed frequently used in travelogues as a synonym for his statue: Hethum, king of Armenia, in 1254, spoke for example of Tibet as the land of the countless ‘Shakmonya’ and ‘Madri’ (the latter term hinting at the statue of Maitreya, the Buddha of the last times).3 Yet Polo refrained from describing Śākyamuni as the founder of an idolatrous religion, realizing that Śākyamuni, while ignoring the Gospels, had so strictly followed their dictates that ‘he would have been a great saint with God if he had been a baptized Christian’. Polo considered it right to exalt him as someone animated by sincere devotion and attributed the origins of the corrupt, idolatrous rites to Śākyamuni’s father, a rich and powerful king who, on being told of his son’s death, had ordered the preparation of a commemorative statue in gold and gems, obliging his subjects to honour him as a god. This idol, the first ever realized, then gave rise to all the others.4

8 Colossal bronze statue of Buddha Śākyamuni (Daibutsu), 7th century. Kamakura, Japan.

9 Colossal wooden statue of St Christopher, 13th century. Barga (Italy), Collegiate Church.

In such an exegesis the Venetian traveller (and his cultivated ghost-writer, Rustichello of Pisa) was probably aware of the theory on the origins of idolatry exposed in the Book of Wisdom (14: 14–20), which attributes the making of the first cult image to an act of despair of a father who had lost his son, and to the vainglory of a king who wanted to simulate his presence and visualize his power in distant provinces. Yet the story may have elaborated in biblical terms one or more narratives on the making of the archetypal image of the Enlightened, which were relatively widespread in medieval Asia.

Such stories traced the practice of image-making to Śakyamūni’s times and stated that the Buddha himself had allowed some of his portraits to be handed down to future generations, usually by the mediation of some prominent king of northern India. According to one tradition, Prasenajit, king of Kosala, had made a sandalwood statue with the head in bone at a moment of absence of Buddha to install it in the Temple of Jetavana at Śrāvastī. When the Enlightened returned to earth, the image had miraculously turned towards him, and he addressed these words to it: ‘Please return to your place. After my nirvana you will be the model from which my followers will obtain their images.’5 Another sovereign, Bimbisāra of Magadha, wanted to render homage to his ally Udrayana of Roruka by presenting him with a portrait of the Enlightened. To enable his court painters to make the likeness as accurate as possible, he asked the Buddha himself to pose for them. When they found themselves facing him, the artists were unable to stand the intensity of his gaze and could not depict him until he projected his shade onto their canvas, enabling them to fill the contours with colour. The Enlightened wrote to King Udrayana and asked him to receive his image with all the honours due to a sovereign.6

But the legend that enjoyed the greatest popularity featured another king, contemporary of Śākyamuni, Udāyana of Kauśambī. According to one version it concerned a painting on fabric, to another a gilded sandalwood statue that, on the Buddha’s return, glided towards him, making him promise that anyone who, in future centuries, venerated it with flags, flowers and incense would receive the gift of contemplating his face. According to another version, the artist in charge of executing the work was transported directly to the heavens so that he could closely observe ‘the distinctive signs of the body of Buddha’ and reproduce them perfectly in the sacred image.7

The sandalwood statue at Kauśambī seems to have played a distinctive role in public devotion. According to Hsüan-Tsang, writing in the 630s or 640s, a large monastery in the old city preserved the work made for King Udāyana. The Chinese pilgrim was struck by the observation that it ‘produces a divine light, which from time to time shines forth’. Many kings had unsuccessfully tried to appropriate this archetypal object and many towns had provided themselves with replicas that were said to be the original. Hsüan-Tsang reassured his readers that only the image in Kauśambī was to be venerated as a lifetime portrait of the Enlightened.8 He was clearly unaware of the later narrative which claimed that the image had been first transferred to the central Asian town of Kucha by Kumarayana and then brought by his son Kumarajiva to China in the fourth century, about two hundred years before Hsüan-Tsang’s travels. In 987 the Japanese pilgrim Chonen saw it in the Imperial Palace in Kai-Feng and immediately commissioned a copy, which poured out a drop of blood as soon as the sculptor started carving it. This prodigious sign made evident that the replica of the archetypal portrait corresponded not only metaphorically to the Buddha’s body, but also coalesced with it.

The work was brought to Japan and is still venerated in the Seiryo-ji Temple in Kyoto (illus. 10) as the original sandalwood statue of King Udāyana. According to some versions, Chonen had actually taken the archetype and substituted it with the copy. It is an almost lifelike image, measuring 162.6 cm in height, and its sacral meaning has been strengthened, as revealed by a recent restoration, by the inclusion in its interior of relics (śarīra), jewels, small reproductions of stupas, statuettes and cartridges containing some of the most venerable sūtras.9 In its turn, it has stimulated the making of replicas, which eventually became objects of public veneration, as is the case with the titular image of the Saidai-ji Temple in Nara (illus. 11). This was made on the initiative of the monk Eizōn (1201–1290), founder of the Buddhist school of Shingon Ritsu, who took the trouble not only to imitate its exterior appearance, but also to provide it with a comparably venerable selection of relics and holy objects. The setting of the statue contributes to its perception as an especially devotion-worthy object: set within a wooden tabernacle in a rather dark space, it is usually inaccessible to beholders, inasmuch as it is mostly covered with curtains. Apart from public exposure on occasions of special festivities, the image can hardly be used as an object of visual contemplation; on the contrary, its limited visibility is deliberately emphasized by the frame, the scarce light conditions and the veils hanging over it.10

The Kyoto image and its copies can be seen as the final outcome of a long process of cultic invention that aimed to assert the existence and authority of a few lifetime portraits of the Enlightened. They implied that image-veneration should be accepted or even encouraged, since it enabled Buddhist believers to replicate, at least to some extent, the visual access to the Buddha’s face that had been granted to his contemporaries. Statues were legitimate, provided they conformed to the visual conventions established by these legendary archetypes. The latter were distinguished from all other images by the circumstances of their execution: they were the result of artists’ direct inspection of the Buddha’s face, which sometimes had taken place only after the intervention of the Enl...