![]()

1

Birth of the Laboratory

Wolfgang von Hohenlohe and Weikersheim, 1590s

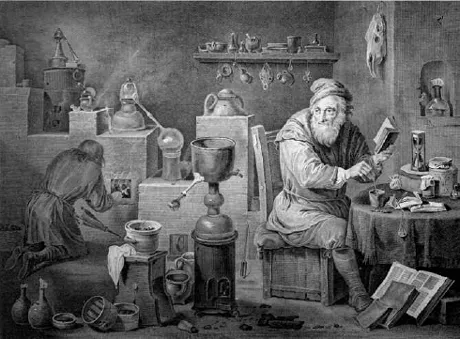

When most people think of the forerunner of the chemical laboratory, they think of a cluttered and dirty alchemical den as painted by artists such as David Teniers the Younger. However, as described in the next section (see page 20), the usual artistic representation of the alchemical laboratory was inaccurate. Nevertheless, there are a few seemingly accurate illustrations, and the reconstruction of an alchemical laboratory based on original documents at Schloss Weikersheim in Germany (see page 27). While the alchemical laboratory may have had some influence on the chemical laboratory of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was not the only prototype.

The Origins of the Chemical Laboratory

One of the most important forerunners of the chemical laboratory was the pharmacy, and it is perhaps no coincidence that the chemical laboratory first arose at the same time as Paracelsus’s concepts of chemical medicine (iatrochemistry). The modern laboratory clearly owes much to the manufacturing pharmacy, which made both plant-based and chemical medicines in line with the teachings of Paracelsus: the pharmaceutical laboratory of Annibal Barlet is discussed in chapter Three, and Apothecaries’ Hall in London played an important role in the development of the laboratory. The chemical laboratory copied the pharmacy in many respects, not least in the long counters favoured by pharmacists. Metallurgical workplaces – something between laboratories and factories – were another starting point for later chemical laboratories. This is fortunate as there are more reliable illustrations of the metallurgical workshop than the pharmaceutical laboratory, and the organization of the metallurgical laboratory is discussed in this book in some detail. Finally, there were other industrial sites that were to some extent forerunners of the chemical laboratory. There were the spirit distillers from the early sixteenth century onwards, whose operations would have been on a relatively small scale, and the soap boilers who would have carried out chemical operations of various kinds. Indeed, some of the earliest references to a work laboratory, albeit in the early nineteenth century, place chemical operations in soap-boilers’ factories. The industrial laboratory is discussed further in chapter Nine.

How Did Laboratories Begin?

There are several approaches to the issue of the beginnings of the chemical laboratory. In the introduction the chemical laboratory is defined as a room or building used more or less exclusively for the practice of chemistry. However, we are mainly interested in rooms or buildings specifically designed for the practice of chemistry. For the origins of the laboratory this distinction is an important one. Doubtlessly early pharmacists, metal refiners and alchemists had workshops or at least rooms that were set up for the practice of their craft. These rooms would have contained some kind of furnace and more than likely some type of distillation apparatus. The bringing together of this equipment into a space set aside at least on a temporary basis for the practice of the alchemical craft could be said to constitute the beginning of the laboratory. However, it is hardly possible to date the beginning of this practice, or to even determine in which part of the world it took place, although Egypt perhaps around the beginning of the Christian Era is as strong a candidate as any. A workshop in early Christian Era Egypt may have contained an alembic or two, a water bath and a furnace, among other apparatus. Such an ensemble can fairly be called a laboratory, albeit only with hindsight and a little imagination.

On the other hand, if we seek a building or room specifically designed for the practice of the chemical arts, we have to look much later. While alchemists and early metallurgists probably gave some thought to the positioning of their apparatus and the nature of the room – ventilation was obviously an important factor, for comfort at least – it is unlikely that any medieval alchemists sat down and designed a laboratory, although the metallurgists appear to have been more systematic.1 The ‘chemical house’ of Andreas Libavius in 1606 was probably the first laboratory to be consciously designed, although it was never constructed and was in fact developed for purely rhetorical purposes. Ironically, as discussed later in this chapter (see page 33), it was probably not of a good design, if only because it was poorly ventilated.

Alternatively, the issue can be approached as a textual question: when was the word ‘laboratory’ first used in the sense of a building or room utilized by a practitioner of the chemical arts? It is interesting to note that the term ‘laboratory’ in Latin and German in the 1560s referred to God’s laboratory or nature’s laboratory rather than a physical entity.2 Twenty years later, however, it was used in Latin for the workplace of an alchemist or pharmacist.3 According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) the first use of the word in English was by John Dee in The Compendious Rehearsall (1592). A few years later Ben Jonson makes its meaning clear – ‘A laboratory, or Alchymists workehouse’ – in the stage directions of ‘Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists’ (1615), which is based on the Dialogus Mercurii, Alchymistae et Naturae (1607) by the Polish alchemist Michael Sendivogius.4 Somewhat surprisingly, ‘laboratory’ actually predates the more anachronistic word ‘elaboratory’, which first appeared in 1652, according to the OED, in John Evelyn’s State of France. The appearance of the word ‘laboratory’ in the 1590s, followed by Libavius’s hypothetical chemical house in 1606, shows how the idea of the laboratory came to the fore at the end of the sixteenth century, culminating in the setting up of a ‘public chemical laboratory’ by Johannes Hartmann, the first professor of chemical medicine at the University of Marburg, in 1609. So what did these early laboratories contain?

Fact or Fiction?

The few contemporary and unbiased images of early modern laboratories and the similar metallurgical workshops show tidy and clean workplaces. However, some well-known pictures of alchemical workshops were created by the opponents of alchemy, not its supporters. It hardly seems necessary to state the obvious fact that most etchings and paintings of alchemical laboratories were not drawn from life or even during the period they allegedly illustrated, but several well-known historians of alchemy between the 1940s and ’60s took them at face value.5 Alchemists themselves tended to produce allegorical pictures that cannot be considered to be factually accurate or representative. Regardless of the subject, filling pictures with still-life objects allowed a painter to show off his skills. Furthermore, an artist had to exaggerate the size of the equipment and tools used by the chemical worker to make them visible in the picture. Hence the scenes portrayed can look unfairly cluttered and disordered, as in the famous picture of a metallurgical workshop by Hans Weiditz in 1520 (illus. 3). This etching raises two important points about such pictures. Representations of metallurgical workshops in the well-known works by Agricola and Ercker were more accurate and more detailed than the few unbiased pictures of alchemical laboratories. The Weiditz etching, however, appeared not in a treatise about metallurgy, but in a volume of moral philosophy, suggesting that most pictures of alchemical laboratories in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had a moralizing purpose.

3 Hans Weiditz, The Alchemist, 1520.

It has to be borne in mind that alchemists were often the subject of moral censure, even if this censure had faded to mild satire by the time of David Teniers the Younger in the late seventeenth century. First and foremost, alchemy was generally considered to be fraudulent.6 Alchemists who claimed to be able to transmute base metals into gold were regarded as either deluded or con artists and, to be fair, alchemy did attract a fair number of confidence tricksters. Medieval Catholics regarded alchemy as a heresy closely allied to Gnosticism. Luther himself approved of alchemy, which he saw as covering metallurgy and pharmacy, as both economically valuable and spiritually symbolic. Other Protestants, who believed in the moral value of hard work, stigmatized alchemy as a way of getting rich quickly without putting in the work, in much the same way that their successors deplore modern celebrity culture. That alchemy, for most of its practitioners, was actually an easy way of becoming poor quickly was neither here nor there. It is more than likely that some alchemists became mentally unbalanced, either because of the effect of working with heavy metals in confined conditions, or due to the stress of trying to find the philosophers’ stone with the constant threat of being punished by the state or Church while their funds were running out. Alchemists had to carry out their activities in secret, partly because of official disapproval and because there would be no point in being able to make gold from lead if anyone could copy their process. During the Middle Ages and the Reformation, groups that took part in secret activities were regarded with suspicion and hostility.

4 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Alchemist, c. 1558.

5 David Teniers the Younger, The Alchemist, 1650.

The classic satirical image of the alchemist’s laboratory was painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder around 1558, some three decades after Weiditz’s moralizing etching (illus. 4). Not only is the satire clear from the picture, which depicts children being neglected and taken into care, and the desperation of the alchemists and their assistants to find the philosophers’ stone (their facial expressions are similar to those drawn by Weiditz), but the Latin motto at the base of the painting also mocks the alchemists’ activities. Bruegel’s approach was adopted a century later by his fellow Netherlandist genre painter David Teniers the Younger (illus. 5). As Teniers is well known among chemists and historians of chemistry for his paintings of alchemy, it has to be stressed that the painting of alchemical laboratories was a very minor activity for Teniers (as it had been for Bruegel), because he only painted 22 alchemical scenes out of a total of 900 paintings. The sheer number of his paintings shows that he was creating paintings en masse for a growing and increasingly wealthy bourgeois audience. The typical Dutch burgher would have disapproved of alchemy as morally dubious ‘get-rich-quick’ superstition, in common with the German Lutheran bourgeois schools’ inspector Libavius, whose ideal chemical laboratory was a typical burgher house (see below). At the same time, alchemy was already receding into the past, at least in bourgeois Dutch circles, and Teniers’s satire is gentle whimsy rather than the severe moral censure of Bruegel. His alchemists are kindly old men (not unlike Santa Claus), who are perhaps forgetful and deluded, but not evil or even untidy – with one or two exceptions.

It might be thought that a more accurate picture of the early-modern laboratory could be obtained from archaeological excavations, notably the ongoing research on the laboratory at Oberstockstall in Austria. The findings from Oberstockstall and other sites, such as the late seventeenth-century chemical laboratory in Oxford, shed light on what apparatus early chemical workers used and hence what they were doing, but they do not tell us much about the space in which this work was done.7

Medieval Assaying Laboratory

The best (and as far as we can tell, the most accurate) illustrations of a medieval chemical working space are of the metallurgical workshop or the assaying laboratory – if we can call it that – in the woodcuts in Georgius Agricola’s De re metallica (On the Nature of Metals) of 1556 and Lazarus Ercker’s Beschreibung aller furnemisten mineralischen Ertzt vnnd Bergtwercks arten (Description of the Most Important Mineral Ores and Methods of Mining) of 1574.8 The illustrations of the laboratory in Ercker provide an immediate impression of tidiness and order, of careful arrangement and space. The retorts are kept in a rack on the wall and the furnaces are neatly lined up. The work is done in the clear space in the centre of the workshop away from the furnaces. The workshop is clearly arranged for assaying, testing and experimental work such as the separation of gold from mercury, and not for the large-scale production of metals. However, the workshop did produce the strong acids it required by distillation, so that the scales of the laboratory in general and the furnaces in particular are no l...