![]()

Charles Marville, Cabinet Dorion, avenue des Champs-Elysées, Paris, c. 1870.

1 The Civilizing Bathroom

This story of the modern bathroom begins in England, at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Among many other wonders, the exhibition featured public conveniences for the use of both women and men. The experiment proved to be a popular success: at the exhibition’s close, the conveniences were reported to have been used 827,820 times in total and, at a penny or halfpenny charge per use, raised £2,441, 15 shillings and 9 pence.1

The Great Exhibition deserves to be seen as a breakthrough moment for the modern bathroom not only because it was the first time that provisions of this kind were made for the public, but also because its organizers placed such emphasis on them. Well in advance of the Great Exhibition, its organizing body, the Society of Arts, stated its belief that such facilities should be a priority, sending a ‘numerously and respectably signed’ petition to pressure the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers to build more in London. Although the Public Health Act 1848 had authorized the building of public necessaries for sanitary reasons, the petitioners were less motivated by health concerns than by civic pride: they argued that conveniences should be provided because foreign visitors were ‘accustomed’ to them.2 Conveniences projected an image of an enlightened city committed to its citizens’ comfort. And, in an age of growing metropolitan competition, there was a keen awareness of which cities offered such amenities and which ones did not. Londoners did not want to be caught short.

Charles Marville, urinal, rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin, Paris, c. 1870.

William Haywood, ‘General Plan of the City of London Shewing the Public Sewers’, 1854. Urinals are indicated by red dots.

The feeling of metropolitan rivalry intensified as plans took shape for the Great Exhibition, itself a competitive event showcasing different countries’ manufacturing capabilities. In London, one rival city loomed especially large: Paris, the host of all of previous industrial expositions of note and a place well equipped with conveniences. These ranged from elegant, privately run ‘cabinets’ to public urinals: thanks to its energetic prefect Claude-Philibert Barthelot, Count of Rambuteau, Paris had 468 of the latter by 1843.3 The Commissioners of Sewers of the City of London asked their surveyor, William Haywood, to study the situation. He reported that the City presently had 75 urinals, mostly located in churchyards or on public thoroughfares, and noted that it would be possible to also build public water closets were the Commissioners to deem it ‘expedient’.4 They did not, maintaining that 34 new urinals alone would meet demand.

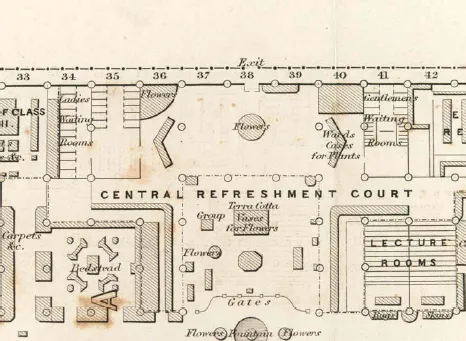

Detail of plan of the Great Exhibition, London, 1851, showing central Ladies and Gentlemen’s Waiting Rooms.

Frustrated by the general lack of action, petitioners sent in a second, even more impressively signed letter on the subject of conveniences, this time with Charles Dickens and Thomas Carlyle lending their names to the cause.5 When it became evident that the Commissioners of Sewers would not take action, the Society of Arts focused its reforming energies on the Great Exhibition instead. It entrusted the task of designing the Crystal Palace’s facilities to leading sanitary engineer George Jennings, who fitted them up with simplified water closets (toilets), dubbed ‘monkey closets’, that were resilient and easy to use – the forerunners of today’s one-piece pedestal models. Run by a staff of 21 attendants, the facilities were located off each of the Crystal Palace’s three Refreshment Courts, conveniently close to visitors washing down their potted meats and jellies with Schweppes soda water and ginger beer. These facilities included both ‘waiting rooms’ (with water closets) and washing places.

It is hard to overstate the impact of these conveniences, which were used by 14 per cent of all visitors to the exhibition, 11,171 on one day alone. At least some visitors would never before have seen, let alone used, a plumbed-in water closet. Even prior to the official opening of the exhibition, Jennings boasted that his WCs had been used daily by over 4,000 workmen yet remained as ‘sweet’ as when first installed.6 Many visitors from other cities and countries returned to their homes inspired by the Crystal Palace’s example: for instance, after returning from the exhibition, the radical politician James Moir began a vigorous crusade to put public conveniences in Glasgow’s streets.7

That the Society of Arts always intended to make a larger point through these facilities is obvious in its final report to Parliament on the Great Exhibition. Pointing to the conveniences’ great success, the organizers urged that similar provisions be made at all future events to alleviate ‘the sufferings which must be endured by all, but more especially by females … on account of the want of them’. Women had been provided with more water closets than men (47 versus 22) but organizers suggested that more should have been installed to meet demand. While this view was enlightened for the day, it was also financially sound: because men used the 54 urinals for free, women accounted for the bulk of revenue from the facilities – £2,084 of the total £2,441.8

There is a final footnote to this story. Refusing to abandon its fight with the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, the Society of Arts invited some of its most illustrious members, the Earl of Carlisle, the Earl Granville, Sir Samuel Morton Peto and Sir Henry Cole, to oversee the establishment of two model conveniences in London in May 1852, with the aim of demonstrating that such facilities would be welcomed by the public and could be financially self-sustaining.9 The Gentlemen’s was located at 95 Fleet Street and the Ladies at 52 Bedford Street off the Strand. Both were accessed through existing businesses and were equipped with water closets, sinks, clothes brushes and full-time attendants. One penny was charged for the use of a water closet; two or three pence was charged for the use of a sink to wash and freshen up. Among others, the tile maker Herbert Minton and George Jennings donated equipment to this venture, which was publicized extensively in The Times and through the distribution of over 50,000 handbills.

Yet despite the triumphant precedent of the Crystal Palace, these conveniences closed after six months due to low user numbers. The committee members gave the failure a decidedly patriotic spin, thus reversing many of their previous claims. ‘It would appear’, they noted:

that the English public do not really require such conveniences to the extent they are wanted abroad. There, the water-closets in private houses, and even in the most magnificent Cafes are of a most imperfect and even disgusting description, and it is the habitual custom of foreigners to frequent the ‘Cabinets’ established for this especial purpose. In England, on the contrary, almost every house, even the humblest, is now provided with these conveniences to an extent which strikes foreigners with as much admiration as any we may have for the establishments in their streets; and therefore, an Englishman rarely requires anything more than an ordinary urinal in the streets.10

These experiments to provide British men and women with public facilities helps illuminate where London stood on sanitary issues in the mid-nineteenth century. As the Society of Arts’s members concluded after their second initiative’s failure, bathrooms were still largely regarded as private concerns: water closets were situated in individual residences and were not integrated into a coordinated public water system. But the amount of time and energy devoted to convenience issues suggests that the mood was changing; a more civic-minded approach was on the horizon. In fact, over the next five decades the ‘sanitary idea’ would emerge as a major government preoccupation and the provision and oversight of water closets and conveniences, along with bath and wash houses, would be recognized as key to improving the environmental and social conditions of the metropolis. And through developments in legislation, infrastructure, plumbing, architecture, science and marketing, the bathroom was gradually hooked up to an integrated system of sanitary control.

The sanitary idea

A common starting point for histories of modern sanitation is the decision to build London’s sewer system in 1858. But the above quote – where the failure of public conveniences is blamed on the prevalence of private ones – reminds us that the situation was more complicated. In reality, the rise of the water closet pre-dated the rise of a comprehensive sewer system, and precipitated the need for it.

The water closet had been a regular feature of aristocratic homes since the last decades of the eighteenth century; however, they were expensive items that required the installation of cisterns, tanks and pumps to supply a steady water supply. This situation changed when private water companies began installing water-carriage systems in London, mostly in the first decade of the nineteenth century, making a reliable water supply available to a greater number. Water closets proliferated among those who could afford them: by 1850, for instance, 65 per cent of homes in wealthy St James’s parish in Westminster had one.11 This proliferation was a disaster in public health terms. The overflow from cesspits made its way into ‘sewers’ that were, for the most part, natural streams and rivers that emptied directly into the Thames. (In stark contrast to most other cities, whose sewers were used for surface water only, it had been legal for London households to connect their cesspools to the common sewers since 1815.) In this way, water closets were responsible for much of the pollution of London’s main water supply, which, ironically, would make a modern sewer system a necessity.

Because London was the world’s largest and fastest growing metropolis, with well over 2.5 million inhabitants by mid-century, it was one of the first to confront the reality that its environmental problems needed to be dealt with in a coordinated way across the city. An important first step was taken when a single unified body, the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, was created in 1847 to replace the eight distinct commissions that had overseen sewers previously. The next year then saw passing of the Public Health Act 1848, which laid the ground for the establishment of a General Board of Health and smaller local boards. The social reformer Edwin Chadwick, whose research and lobbying had done most to usher in these changes, was convinced that good drainage was the best means of improving public health. Like most of his contemporaries, he believed infectious diseases were transmitted through the air in miasmas bred by putrefying waste, hence the best mode of prevention would be to quickly flush or drain waste away before it stagnated. Chadwick’s obsession with effective drainage would reshape the government’s approach dramatically over the next decade, as resources were redirected from street cleaning and nuisance removal towards building a water system that provided clean water and sewage disposal.

The new Public Health Act’s clauses regarding domestic sanitary arrangements are especially significant to this history because it marks the moment when government first entered the private bathroom in a meaningful way. As part of its mandate to prevent noxious miasmas, the Act stipulated that any newly built or rebuilt house be provided with a ‘sufficient watercloset or privy and an ashpit, furnished with proper doors and covering’. If the property owner did not comply, the local health board could build the required facility itself and recover the costs. (Some local authorities did proceed to rip out privies and replace them with water closets, with controversial zeal.12) The Public Health Act further stipulated that factories which employed over twenty people of both sexes provide a ‘sufficient’ number of water closets or privies ‘for the separate use of each sex’, or a fine of up to £20 would be levied. Homeowners were now legally required to notify the local board of health in writing prior to constructing a privy or cesspool, and surveyors were given the power to shut down any judged to be a nuisance or ‘injurious to health’. Finally, the local board of health was empowered to erect public conveniences out of district rates, although there was no requirement they do so.13 This resulted in the erection of at least one gentlemen’s public convenience, on Rose Street in Soho in 1849 – if not the first public facility with water closets in the city, then certainly one of the first.14

Even though standards were still loosely defined (what constituted a ‘sufficient’ facility or a ‘sufficient’ number of water closets?) and the local boards’ powers of enforcement were as yet untested by the courts, these clauses were significant, not least because they show that a form of sex segregation was built into public provision from the start. Indeed, given that the Public Health Act’s provisions for factories applied only to workplaces that employed over twenty people of both sexes, we have to ask whether the real concern at this ...