![]()

1

Portrait, Fact and Fiction

I

In the sense that it denoted until very recent times – of a literal visual transcription of any material object or person – portraiture is one of the great defining metaphors of Western culture. Key the word ‘portrait’ (Porträt in German) into the electronic catalogue of any major library and you will access huge numbers of books that are not concerned with portrait painting as such: Portrait of Christ, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Portrait of an Age, Portrait of Provence . . . These titles not only demonstrate the prevalence of portraiture as a genre since the sixteenth century but also, significantly for my argument, make visible the rhetorical and metaphorical possibilities attached to the notion of representing a particular human subject. Portraiture, an art form that seems so very tied to the ‘real’ and the ‘natural’, thereby signals its connection to imagination, memory and the spiritual. It is perhaps therefore unsurprising that portrait representations are ubiquitous in classic nineteenth-century novels (an art form that excelled in its illusion of direct and unmediated access to life as lived); they offer an analogue to the verbal depiction of character, and by sleight of hand, as it were, stage a reality trick. Moreover, the novel is itself, as articulated in Henry James’s preface to The Portrait of a Lady (1881), justified as a kind of investigative portraiture.1

Portraits have long been associated with book production in a material sense: they are frequently reproduced as frontispieces, acting as a kind of portal to the reading of the written text. Frontispieces, as well as portraits scattered through the text, may represent the author of a book or its subject. Given their pre-eminence in the physical entity of the book (they are often the first thing you see after the title page) they have received remarkably little attention from scholars and many libraries do not even catalogue the existence of such images. The practice of ‘grangerizing’, or extra-illustration (also by no means universally recognized by cataloguers), bears witness to readers’ preoccupation with the visual embellishment of written narrative, particularly from the late eighteenth century.2 Portraits reproduced in books should not be considered innocuous: how often do we peer at an author’s mug shot on the back of a paperback, silently trying to forge a connection? Equally portraits described or invoked in books carry a particular narrative charge: there is a moment in Joseph Roth’s The Radetzky March when, as we shall later see, a child repeatedly scrutinizes a portrait but the dead man reveals nothing and the boy learns nothing; our overweening confidence that the power of images outlasts us (a confidence upon which both private and public portrait galleries, and portraits reproduced in history books, are predicated) is held up to an unforgiving light. Some of the ways in which historical narratives are over-determined by the galleries of portraits they reproduce may be gauged by looking briefly at one canonical example.

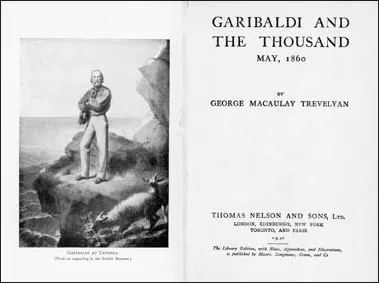

Garibaldi at Caprera shows a portrait devoid of monetary value and one that is unlikely to inspire by its material or aesthetic qualities (illus. 2). It is, however, an image characteristic of the dominant way in which portraits are annexed to the service of historical narratives with consequences that are undeclared and thereby naturalized. This depiction of Garibaldi is a reproduction of a photograph of a copy of a many times copied portrait of the popular guerrilla hero of Italian liberation.3 It is, in a literal sense, a pre-text. It is unlikely that Garibaldi posed for an artist standing, above tumultuous waves, on this very insecure looking rocky outcrop on a hillside where only sure-footed goats dare to venture. Nor is it probable that Garibaldi looked anything like this slim figure in his clean, pressed trousers. The portrait here offers no reliable material evidence whatsoever. But its deployment for mass circulation as the frontispiece to the edition published in 1931 of G. M. Trevelyan’s book about the hero of the Risorgimento provides a wealth of evidence both historical and historiographical.4 The relationship between the page on the left and that on the right is dynamic and dialectical. The solitary situation of Garibaldi might be that of a meditative nature-lover in national dress such as those depicted by Caspar David Friedrich. However, the bold black words ‘. . . and the Thousand’ interact with the image to produce a trope familiar from countless military accounts from antiquity to the present of the ‘eve of battle’ loneliness of the commander: he is the one who, rocky and indomitable, leads and commands the loyalty of the many, and who is responsible not only for the military outcome but for the welfare of his men and – through them – of the people at large.

The fact that this is the sole image chosen for volume I of this library edition – destined to be used in countless classrooms5– enables us to draw a simple enough, but nonetheless valuable, conclusion. The view of Garibaldi as resolute (arms folded), strong (rock-like and dominating his environment), local (his regionally particular clothing), brave and sure-footed was by 1931 an orthodoxy. A portrait deriving its iconic force from the very fact that it is a much-multiplied image affects, or even possibly determines, the way other forms of historical evidence are processed and how historical narratives are interpreted by readers. The portrait, as frontispiece, is our first view of the book’s subject; it is what we see before we read any words about Garibaldi and his achievements. The reproduced portrait, with its manifest blend of fact, fiction and familiarity, works to endow the historical narrative with its illusion of a unified subject, serving simultaneously to monumentalize the status of knowledge in historical discourse concerning Garibaldi and his followers and to guarantee its veracity by the illusion of videre, of having been seen.

If one were to follow this through it might be possible to argue that reproduced portraits of historical personages not only raise questions of historiography (as this one clearly does) but work in an unacknowledged way as a filter for other kinds of evidence. The portrait appended to the historical account might therefore be described as instantiating what Jacques Derrida proposed as the ‘there where things commence – physical, historical, or ontological principle’ that is part of the notion arkhé upon which the modern concept of ‘archive’ has been constructed. Nonetheless Derrida’s formulation, though helpful in terms of temporality, has insufficient accommodation for the idea of materiality of the portrait (its physical presence as an object), to which I will return.6

In view of this it is perhaps not surprising that historians have sometimes attempted to establish images as portraits of particular individuals in support of an historical hypothesis. Art history has by and large learned to proceed cautiously with regard to written sources.7 Historians of portraiture recognize the role of convention, style, protocol and what has been called ‘staging’, the peculiar nexus of psychic and social conditions attendant upon a portrait sitting.8 We also acknowledge that, even where an artist is known to have seen the subject (which is by no means invariably the case), there is an element of the fictive involved in portrait representation. We must therefore regard as fallacious methods which attempt to employ a portrait as though it were a substitute for the living human form, or treat portrait representations as though they were medical records. The possibilities for divergent readings of a face due to lighting, medium or a host of other conditions are vast and death masks are themselves artefacts rather than faces, their appearance the result of mortuary practices and technologies of casting and modelling. Dismantling bodies or faces in portraits into their constituent parts, whether by Morellian techniques or by the methods of forensic pathology, may satisfy the desire to grasp the past and lay it, as it were, on the anatomy table but the conclusions thus reached are, I believe, unconvincing.9 It is not simply that the visual is both historically specific and irreducible but that representations of humans viewed by other humans set up particular kinds of social and psychic dynamics. It is these that offer a rich field of historical evidence; it is a field best approached obliquely.

Nonetheless history and portraiture deserve attention as a duo we live with, even while knowing this symbiosis to be an illusory effect, socially contrived, culturally orchestrated and by no means universal. The Times in 2002 was much preoccupied with possible reasons why the British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, refused to sit for his portrait; the newspaper commissioned an image showing what he might look like were Lucien Freud to paint him.10 The unspoken assumption was that Blair feared the modernist aesthetic of one of England’s then most distinguished living artists might not show him as he saw himself – a universal problem for portrait subjects and, particularly, for the rich and powerful conscious of the public exposure. Scholarly and academic studies of individual portraits, portrait painters and portrait phenomena have proliferated during the past two decades. And yet we seem no nearer to understanding what governs portraiture’s contribution to the conviction of historical accounts, the ways in which a portrait might be understood to offer forms of historical evidence, or indeed what precisely we are prepared to accept as historical evidence (as opposed to subjective judgement) in any given portrait image.

This is perhaps surprising given major shifts over the past two decades within historical studies from a document- and data-driven approach to methodologies that embrace cultural forms of evidence.11 Herbert Butterfield’s historian of the mid-1950s is an omniscient figure who, it is suggested, might best succeed if he (sic) were to unload his mind ‘of all hypotheses . . . collect his facts and amass his microscopic details’ before placing everything in chronological order.12 By this account history is about dovetailing joints that are, it goes without saying, written, and fiction is a form of artifice that is anathema to the dutiful historian.13 By contrast, in a volume edited by the late Roy Porter, the historian Roger Smith affirms the status of portraiture as ‘one sign of the growth of reference to individual status in late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe’.14 An essay (for example, by Montaigne) is unlike a treatise but, Smith argues, like a portrait, it must claim to be particular rather than universal. But pushed to define what the portrait offers the historian by way of evidence, Smith resorts to the example of Rembrandt’s self-portraits, which he describes as ‘a profound emblem of the self’. But emblems such as those employed by Cosimo de’ Medici or Queen Elizabeth I gain their potency by not being a representation of the subject’s face but rather a metaphorical abstraction of their presumed qualities. His essay typifies the approach of enlightened historians such as Peter Burke who, since the 1980s, have given serious cognizance to cultural phenomena in their efforts to understand social change.15 The problem is that formulations such as ‘emblem of self’ and generalizations, however convincing, about the evolution of a genre foreclose on the tricky question of what exactly a historical portrait tells us about the past (or about acts of portrayal), whether individual or collective; and the tendency is, as we have just seen, to extrapolate the collective from the individual.

Portraiture is a slippery and seductive art; it encourages us to feel that then is now and now is then. It seems to offer factual data while simultaneously inviting a subjective response. It offers – in its finest manifestations – an illusion of timelessness, the impression that we can know people other than ourselves and, especially, those among the unnumbered and voiceless dead. Carlyle’s declaration that a portrait put him in touch with an individual from the past was pivotal to the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery in London and underpins other portrait galleries around the world, such as those in Washington DC and Canberra, Australia.16 Carlyle is by no means alone. Many are the thinking and sensitive observers who have been seduced in this way, setting aside their rationalist scepticism to engage with portraits. Sigmund Freud, trained as a natural scientist, made a point when in London in 1908 of visiting the National Portrait Gallery where, seeking laws that might govern a quixotic art form, he recorded his impressions of the physiognomies before him. ‘Born writers seem to be those who remained childish’; ‘Famous women plain on principle’.17

The illusion of closing the gap of time and space that portraits seem to provide suggests that they work precisely in the opposite way from documentary evidence, at least according to Michel de Certeau’s interesting observations on the writing of history. The writing of history, he claims, ‘places populations of the dead on stage – characters, mentalities, or prizes.’18 For de Certeau the line of portraits arranged dynastically dictates spatially how a visitor follows a narrative itinerary of the dead and this, he suggests, provides an historiographical blueprint for the writing of history, which is ‘gallery-like’ and includes visual signs. But the specific function of writing history is, according to de Certeau, a kind of burial rite, a means of exorcizing death by inserting it into discourse. History writing also, he argues, allows a society to situate itself by giving itself a past through language, thus enabling it to create a space of its own distinct from that of its past.19 If we followed that line of argument we could conclude that today’s populist and museological cult of ‘then is now’, with visitors invited to dress up in replica period clothing and experience sounds and smells as well as sights, would be understood as a protective psychic manoeuvre: by feeling familiar with the dead we can separate ourselves from them. I find much that is persuasive in de Certeau’s account but his paradigm of the gallery of portraits hinges on the schematized dynastic hang that originates in the family tree and is found throughout Europe from the seventeenth century. It ignores the mainspring of the individual portrait that is so appealing precisely because it blurs the notion of temporal distance, creating an illusion of intimacy with a particular dead person.

The incorporation of portraits into historical accounts may have something to do with the centrality of sight to notions of trust, truth and reliance. As Derrida points out, ‘before doubt ever becomes a system, skepsis has to do with the eyes’. The word ‘skepsis’ refers to a visual perception, to the observation, vigilance and attenuation of the gaze during an examination.20 Among the Oxford English Dictionary’s multiple definitions of the word ‘evidence’, ideas concerning ‘a document by means of which a fact is established’ or ‘the language of documents, or the production of material objects’ come very low down. The word ‘evidence’ comes from videre, to see, and its earliest uses, in the fourteenth century, concern ‘an appearance from which inferences may be drawn; an indication, mark, sign, token, trace’. But faces as signs, as the struggle of physiognomists from antiquit...