![]()

| ONE FROM LEGEND TO HISTORY |

In the summer of AD 376, two Germanic tribes descended upon the Danube river frontier of the Roman empire. They were the Tervingi and Greuthungi Goths, who had previously lived beyond the limits of Roman power in the lands circling the northern coast of the Black Sea. And they came not as raiders seeking plunder, but as refugees. Men, women and children, numbering in the tens of thousands, gathered in camps along the banks of the Danube while their leaders requested permission to settle within the empire. According to the contemporary Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus in his Res Gestae, the Goths ‘sent agents to Valens [the eastern Roman emperor], humbly begging to be admitted to his dominions, and promising that they would live quietly and supply him with soldiers if the need arose’ (31.4).

Who were the Goths, and where did they first come from? As we will see throughout this book, these are questions that have been debated for nearly two millennia. In the search for Gothic origins, the line between legend and history becomes very hard to draw. The Goths themselves left no written records before they entered the Roman world, for theirs was an oral culture whose traditions were passed on by word of mouth. Most Roman sources are unsurprisingly hostile to the Germanic barbarians who threatened the empire, and while Ammianus Marcellinus is unusually even-handed he provides little information on the Goths before the second half of the fourth century. For the period preceding close contact between Goths and Romans, we therefore depend heavily upon the only major historical work actually written by a Goth: the De origine actibusque Getarum (The Origin and Deeds of the Getae/Goths) or Getica of Jordanes.

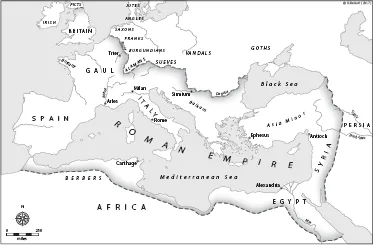

The Roman world in AD 300.

Jordanes was no ‘barbarian’ Goth. Fiercely proud of his Gothic heritage, he was also well educated in Greek and Latin and he drew upon a number of Roman writings (some of which are now lost) when he compiled his Getica in the imperial city of Constantinople around the year AD 551. Given that he wrote almost 180 years after the Tervingi and Greuthungi arrived at the Danube river, Jordanes was inevitably biased by his knowledge of later Gothic history, which at times distorted his account. But he offers our clearest vision of how the Goths remembered their distant past, and combined Roman literary sources and Gothic oral tradition into a single sweeping narrative that has exerted enormous influence on all subsequent interpretations of the Goths and their origins.

The mighty sea has in its arctic region, that is in the north, a great island named Scandza, from which my tale (by God’s grace) shall take its beginning. For the race whose origin you ask to know burst forth like a swarm of bees from the midst of this island and came into the land of Europe (Getica 1).

This island of Scandza, also described by Jordanes as ‘a hive of races (officina gentium) or a womb of nations (vagina nationum)’ (Getica 4), was the birthplace not only of the Goths but of many other tribes. It is located in the northern ocean opposite the mouth of the river Vistula, which flows through modern Poland into the Baltic Sea. Jordanes’ Scandza thus approximately equates to Scandinavia, from which the Goths set out on their long migrations. Under a king named Berig they left the island and landed in Europe. Several generations later, King Filimer (‘about the fifth since Berig’, Getica 4) led his people further south in search of a more fertile region in which to settle. So the Goths came to western Scythia (roughly modern Ukraine) and resided near the sea of Pontus, the Roman name for the Black Sea.

The Goths flourished in their new homeland. They were brave warriors and hardworking farmers, living in villages under tribal leaders. Jordanes reveals little of the Goths’ pre-Christian spiritual beliefs, which included the veneration of heroic ancestors and the worship of a god of war (identified by the Romans as Mars). Arms were hung from trees in the god’s honour, and captives were slain to appease him in blood. Jordanes’ account hints at parallels between early Gothic religion and the later Scandinavian sagas, parallels which continue to fuel speculation to this day. But while their rites may have been cruel, the Goths did not lack for learning or teachers of philosophy. They are claimed to have studied ethics and logic, astronomy and botany. ‘Wherefore the Goths have ever been wiser than other barbarians and were nearly like the Greeks’ (Getica 5).

Évariste Vital Luminais, Goths Crossing a River, late 19th century, oil on panel.

The Getica, which then proceeds to trace Gothic history from the Scythian settlement right down to Jordanes’ own time in the mid-sixth century, was a remarkable achievement. Setting aside Jordanes’ understandable desire to glorify his people, however, there were two key distortions in his presentation of the early Goths that would have a vast impact on later scholarship. First, Jordanes’ account combined Gothic legends with stories relating to other peoples who inhabited the same territories, notably the Scythians and Dacians, as well as a variety of Germanic tribes. This directly contributed to the tendency for the term ‘Gothic’ to be used in subsequent centuries to refer to all Germanic peoples without distinction (the consequences of that blurring of identities are explored elsewhere in this book). Second, Jordanes wrongly assumed that the separation of the Goths into two clearly defined tribes, the Ostrogoths and the Visigoths, had already existed before the Goths entered the Roman empire. When the Goths lived in Scythia north of the Black Sea,

Part of them who held the eastern region and whose king was Ostrogotha, were called Ostrogoths, that is, eastern Goths, either from his name or from the place. But the rest were called Visigoths, that is, the Goths of the western country (Getica 14).

At the time Jordanes compiled the Getica in c. 551, the Visigoths ruled over Spain, and the eastern Roman empire of Justinian was at war with the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy. It was therefore very easy for him to assume that such clear-cut divisions had long existed. This assumption underlay later reconstructions that equated the Tervingi with the Visigoths and the Greuthungi with the Ostrogoths, or asserted that the Visigoths were those who came to the Danube river in 376 while the Ostrogoths were those who remained in Scythia. As we will see, the reality was far more complex. The events that led to the migration of the Tervingi and Greuthungi destroyed the existing Gothic tribal confederations, and only gradually did new identities emerge.

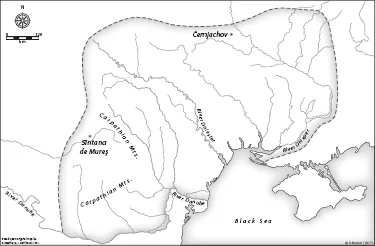

Yet despite these limitations, the broad outline of Jordanes’ narrative of early Gothic history remains largely persuasive. A Scandinavian origin for the Goths cannot be definitively proven or dated, but accords with our sparse knowledge of Gothic tribal customs as well as the oral traditions that Jordanes drew upon. For the Gothic presence north of the Danube river and the Black Sea, we have essential if cautious support from the evidence of archaeology. Material remains discovered from eastern Romania round to the southern Ukraine have revealed the presence of a largely uniform culture that flourished across that region in the mid-third to fourth centuries AD, known today as the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov Culture. The cemeteries at Sîntana de Mureş in central Transylvania and Černjachov near Kiev were both excavated in the early 1900s, and were the first of more than 3,000 sites that have now been associated with this culture. The dating of these sites corresponds with the Gothic domination of the region from the early third century onwards, and the sites have revealed priceless information to help us reconstruct early Gothic society.

The majority of the settlements that have been discovered are located in or near river valleys and are organized around agricultural production. Houses are usually built in wood and earth rather than stone, and sometimes combine human living quarters and animal shelters. Cereals appear to have been the most common crops, especially wheat, barley and millet, and iron ploughshares, sickles and scythes are all regularly found. Animal husbandry as revealed by the survival of bones seems to favour cattle herding but also sheep, goats and pigs. This was not a culture in which hunting or horse riding played a major role. Cemeteries display a range of burial practices, with inhumation gradually becoming more widespread than cremation, and the dead were provided with a variety of grave goods. The most popular finds are pottery, from storage jars and cooking pots to wide shallow bowls (possibly used for drinking) which are common across the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov Culture. A few pieces have been discovered marked with Germanic runes, while Roman pottery (notably wine amphorae) is not unusual. Personal possessions take many forms, including bone combs and metal brooches and belt buckles, but interestingly only rarely feature weapons. The quality of goods buried with a person was a marker of social and economic standing, and while brooches and buckles were usually made of bronze, those of higher status could possess ornaments of silver.

The extent of the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov Culture.

From this archaeological evidence it is possible to draw some broad but significant conclusions. The peoples who lived in the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov Culture were clearly a sedentary agricultural population. The majority were devoted to subsistence farming, and craft production was likewise largely on a local level, with most villages having a pottery kiln and a blacksmith in addition to domestic spinning and weaving. But there was also a degree both of craft specialization, with pottery styles and iron and bronze metalwork common across the culture, and of trade, particularly with the Roman empire. Roman amphorae and glassware were imported, with slaves known to have been taken in return, and Roman coins circulated beyond the Danube river frontier on an increasing scale across the fourth century. The overall uniformity of the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov Culture, however, does not imply that a single ethnic or political society existed in the wide region from the Danube river to the northern Black Sea steppe. Widespread local variations in housing, burial customs and craftwork all suggest diverse tribal identities sharing a broad cultural unity, within which the Goths were almost certainly the dominant force.

The period in which the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov Culture flourished, from the mid-third century to the later fourth century, corresponds very closely with our literary evidence for Roman Gothic relations. The Gothic migration southward to Scythia probably began near the end of the second century AD, and the Goths first came into conflict with Rome during the so-called ‘third-century crisis’ of the Roman empire. In 238 the Goths sacked Histria at the mouth of the Danube, and a decade of ongoing raiding culminated in the Battle of Abrittus in 251, when the Gothic chieftain Cniva defeated and killed the emperor Decius (otherwise remembered chiefly as a persecutor of Christians, who regarded Decius’ fate as divine judgement). Over the next twenty years the Goths also used ships, presumably seized from the maritime cities of the northern Black Sea coast, to raid across the water into Bithynia and Cappadocia in modern day Turkey. The emperors Gallienus (r. 253–68), Claudius II (r. 268–70) and Aurelian (r. 270–75) each won hard-fought victories to drive the Goths back in the Balkans, with Claudius the first emperor to receive the title Gothicus for his achievements. By the end of the third century the Roman frontiers had been secured, but the Goths had extended their presence firmly into the lands north of the Danube.

The Spearhead of Kovel, 3rd century, northwest Ukraine. The Gothic runic inscription may read ‘target rider’.

In the first half of the fourth century, a pattern seems to develop. Peaceful relations between Goths and Romans were now the norm, interspersed with periodic outbreaks of violence. After Constantine became the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity in 312, he fought a civil war with his eastern rival Licinius for control over the empire. Gothic assistance to Licinius led to further conflict once Constantine had defeated his rival, and a Gothic army was crushed in 332 followed by a treaty agreement to regulate the frontier. Jordanes entirely omitted this episode from his Getica, although he does make the impressive albeit imaginary claim that ‘it was the aid of the Goths that enabled him [Constantine] to build the famous city that is named after him’ (21). Thirty years of relative stability lasted until the 360s, when the Goths again intervened on the losing side in a Roman civil war. Valens, who became the eastern emperor in 364 while his brother Valentinian I ruled in the west, defeated the usurper Procopius in 366 and then turned upon Procopius’ Gothic allies. Valens’ campaigns of 367–9 failed to achieve decisive victories, but he disrupted Gothic trade and agriculture and secured a new peace treaty in 369. Ammianus Marcellinus clearly identifies the Goths in question as the Tervingi, and it was their chieftain Athanaric who sealed the agreement with Valens.

A suitable place was chosen for concluding the treaty. Athanaric declared that he was bound by a tremendous oath taken at the behest of his father never to set foot on Roman soil. Since he could not be persuaded to do so, and it would be undignified and degrading for the emperor to cross over to him, the sensible decision was reached to conclude the treaty in mid-stream, the emperor with his guard being conveyed from one bank and the tribal chief with his attendants from the other (Ammianus, Res Gestae 27.5).

The long relationship between the Goths and the Roman empire that had existed since at least the first half of the third century is essential to understanding the subsequent course of Gothic history. When the Tervingi and Greuthungi tribes came to the Danube in 376, they were not strangers to Roman culture. Many Gothic warriors had served in Roman armies, and the leading Goths had a healthy respect for the imperial might of Rome and the benefits that could be gained from engagement with Roman society. The Romans in turn recognized the Goths as formidable fighters, and hoped to use that strength to Rome’s advantage. The treaties of 332 and 369 both sought to keep trade and communications open, and the archaeological evidence confirms the penetration of Roman coinage and artefacts into the Sîntana de Mureş-Černjachov region. As the Goths moved across the empire over the following centuries, the tensions arising between their conflict with Roman power and their admiration for Roman civilization would shape the Gothic kingdoms of Gaul, Italy and Spain.

No less importantly, during t...