![]()

1

THE POLYPHONY OF MUSIC AND PAINTING

The relations between music and painting have become a popular field, as suggested by the extensive bibliography on the subject, and the many exhibitions and conferences devoted to the theme. Museums organize concerts, and musicians look to visual artists for collaborative projects and experimentation. One can almost define the art of the last half century – happenings, performances, sound installations and other Sound Works,1 from Fluxus to musical theatre – in terms of decompartmentalization and the repudiation of frontiers.2 Time has entered the visual arts, just as music now occupies space. Traditional categories no longer hold; in short, Lessing is turning in his grave.

But these interactions are nothing new. Painters have often been drawn to music. Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa surrounded by musicians, Delacroix’s chapel in Saint-Sulpice was painted to the sound of the organ and Jean-Michel Jaquet’s lines followed the heady strains of jazz. Many painters were inspired by composers (Wagner and Bach in particular), and inversely the list of musical works which pay tribute to painting is so long that it has already filled a whole book.3 Musicians were sometimes collectors, for instance Emmanuel Chabrier or the singer Faure, who were among the most generous patrons of the Impressionists. Ernest Chausson, Claude Debussy and Igor Markevitch were discerning enthusiasts, and the artist’s studio, where music figured prominently (as Ary Scheffer, Delacroix and Bazille bear out), was a natural meeting point for painters and artists.4 Salons also played a part in bringing artists, musicians and writers together – around Arthur Fontaine, Henri Lerolle, Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux or the Natansons, for example.

Fruitful collaborations and encounters also took place in work for the stage, particularly opera. One should mention at least Max Slevogt’s5 and Oskar Kokoschka’s stage sets and costumes for The Magic Flute,6 and David Hockney’s for Satie, Ravel, Poulenc and Stravinksy.7 Dance, in which music fills the space, was another favourite field of collaboration, as illustrated by the Ballets Russes8 and the Ballets Suédois. And Wagner’s ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk can still be felt in Kandinsky’s experimentations for the stage, from the Gelber Klang (1912) to the staging, in Dessau in 1928, of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, using lighting effects and coloured forms.

Different sorts of personal relations also played an important role in relations between the arts. There were family relations, for example between brothers (Gerrit Sweelinck painted the portrait of the composer and organist Jan) or from father to son (Henri Dutilleux was the grandson of the painter Constant), couples (Fanny Mendelssohn and Wilhelm Hensel) and also friendships – famously Chopin and Delacroix, or Stravinsky and Picasso, who made portraits of each other.

Sometimes painters were themselves musicians, for instance Leonardo da Vinci, Gaudenzio Ferrari, Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto,9 Domenichino,10 Salvator Rosa, Gainsborough,11 Ingres, Delacroix, Gustave Doré, Redon, Kandinsky, Matisse and MOPP (Max Oppenheimer). The portrait of the artist playing an instrument was another frequent representation, of which the best-known examples are Jacopo Bassano, Evaristo Baschenis, Peter Lely, David Teniers, Jan Steen, Jacob Jordaens, Frans van Mieris, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Gustave Courbet and Max Beckmann. But the list goes on, and includes a number of women: Marietta Robusti, called Tintoretta (daughter of the painter Jacopo), Lavinia Fontana, Sofonisba Anguissola, Artemisia Gentileschi (daughter of Orazio), Catharina van Hemessen (daughter of Jan) or Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun. And, in another variation on this theme, Angelica Kauffmann depicts herself as torn between Music and Painting like a latter-day Hercules at the crossroads.

These combined talents were not restricted to earlier centuries. Mendelssohn was a gifted draughtsman, as was Paul Hindemith, and there have been several exhibitions of John Cage’s work. The sculptor Pradier composed music, Lyonel Feininger wrote fugues and Schönberg’s self-portraits are well known.12 This raises the question of whether certain artists – Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis,13 Alberto Savinio, Henri Nouveau, Michel Ciry and Jean Apothéloz, for example – should be regarded as painters or composers. Louis Soutter turned from the violin to drawing, Robert Strübin from the piano to painting and André Bosshard, the son of the painter and great music lover Rodolphe Théophile, moved on from the flute. It was only after much hesitation that Paul Klee gave up his position as violinist in the Bern Orchestra.

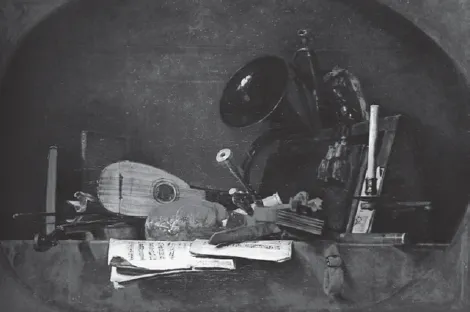

Anne Vallayer-Coster, Still-life, 1770, oil on canvas.

Materializing Music

Artists have always enjoyed representing the world of music,14 and a rich repertory of musical images has accumulated across the centuries. Some portraits stand out, such as Delacroix’s or Ingres’s masterful Paganini, Repine’s Mussorgsky or Stravinsky’s particularly seductive iconography.15 An artist can also be the subject of a musical portrait (for example, Le Travail du peintre, Eluard’s poems set to music by Poulenc, 1956), or even inspire an opera (Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini or Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler).16 Another common theme depicted by artists is the concert, whether sacred, profane, private, public, courtly or popular; or the instruments themselves, particularly those with sensuous forms,17 such as lutes and violins, which have long been used for the challenge of rendering perspective, and which have also figured prominently in many a still-life, from the Baroque to Cubism, Caravaggio or Baschenis to Juan Gris. Other instruments served as the painting’s ‘canvas’: one could fill a whole museum with painted organ doors and harpsichord cases often signed by masters such as Schiavone or Tintoretto.

So dialogues between music and painting took place in the space of the portrait, the genre scene and the still-life. These representations can be used by musicologists as documentary evidence of particular instruments, or as proof of how they were played in different periods, yet the images are not always as straightforward as they may seem. The art historian should issue a word of warning here concerning different levels of meaning, and the symbolic dimension of objects, since without this an interpretation may be anachronistic or simply absurd. For instance, concerts of angels with dozens of musicians playing away, as in Gaudenzio Ferrari’s painting adorning the dome of Saronno near Milan (1536), is no reflection of contemporary reality. It is, first of all, a ‘heavenly’ concert, but it also mixes ‘high’ and ‘low’ instruments, which simply never occurred, for reasons of acoustics. The victory of Apollo’s lyre over Pan’s or Marsyas’ flutes is historically determined,18 and this social hierarchy between strings and wind instruments was anyway never absolute, since bagpipes, usually the preserve of peasants and shepherds, were sometimes played by angels, just as in reality their court version was played in the circle of Marie Antoinette.

Overall, the image of Music is twin-faced, sometimes it is associated with Paradise and spirituality, and sometimes with death (it accompanies the Danses macabres), hell (we need only think of Hieronymus Bosch) and the pleasures of the flesh. Thus the lute, although often paired with the harp (King David) or the organ (St Cecilia), in Memling’s altarpieces for example, was also the favourite instrument of Venus and Venetian courtesans, accompanying dawn love serenades. The violin was heir to Apollo’s or Orpheus’ lyre, but also the attribute of dancing masters, and thus an object of suspicion for Calvinist and Counter-Reformation zealots. These instruments, which were frequently represented in allegorical still-lifes called ‘Vanities’, were thus invested with multiple and sometimes contradictory meanings: as signs of wealth and value (they were often collectors’ items), but also fragility (the broken string) and impermanence (covered in dust, and the sound is no sooner produced than it dies away). Instruments could be associated not only with love, but also with the intellect; music was one of the liberal arts, taught in the Quadrivium alongside arithmetic, geometry and astronomy. The link between music and astronomy often inspired representations of the ancient theme of the Harmony of the Spheres.

Allegory and myth abound in representations of Music. Musica and Pictura are often presented together, like Narcissus and Echo for Ovid or Poussin. The abundant iconography can be divided into two broad categories, the religious and the profane.19 Profane works favour the themes of inspiration (blind Homer playing the viola da gamba), love (Titian’s paintings of Venus) and hearing (in the cycle of the five senses). Mythological scenes include Apollo surrounded by the Muses, Mercury lulling Argus to sleep, Orpheus charming the animals, Arion saved from drowning by a dolphin who has heard him play, and Amphion building the walls of Thebes simply by playing his lyre. To which should be added Pythagoras, the father of music as a mathematical art, with his vibrating string or blacksmith’s hammers. Religious iconography includes the Old Testament figures of Jubal and Tubalcain (the mythical ancestors of instrument-makers), Job and, above all, David, the author of the Psalms whose harp-playing dispelled Saul’s melancholy. In the New Testament, we have the 24 elders-musicians in the Book of Revelation and the apocryphal tales around the Flight into Egypt (Caravaggio). The development of the Cult of the Virgin in the twelfth century inspired the choirs of angels which adorn Nativities, Adorations and Assumptions. The Golden Legend dwelt on the Ecstasies of St Francis and Mary Magdalene. And in the wake of Raphael’s famous painting, St Cecilia tended to replace Musica.20 An erroneous interpretation of a passage in her liturgy generated a whole series of images featuring, especially, the organ.

Ut Musica Pictura

This dialogue between music and painting was also pursued in theoretical writings, where comparisons between painting and music are frequent. Aristotle was the first to unite both disciplines under the principle of mimesis, the imitation of nature, but there existed a difference in their social status. In the paragone debate (the comparison between the arts) initiated by Leonardo, painting attempted to emulate music in order to win for itself the prestige traditionally reserved for the liberal arts (which included music). Alongside this, the art critic’s expanding terminology made frequent borrowings from the domain of music, particularly in the designation of colour, in Venice initially. But there was more to come. In the footsteps of Athanasius Kircher and Newton, the Jesuit Louis-Bertrand Castel devised a set of correspondences between notes and colours. It underpinned his designs for an ocular harpsichord, which was to have a long history despite its utopian nature. With Romanticism, the interest shifted to synaesthesia, and a new search for correspondences began, particularly by E.T.A. Hoffmann, Baudelaire, Scriabin and Kandinsky. ‘Colour music’, and later cinema and video, extended these explorations, which continue right into the present day.

Felix Vallotton, La Symphonie, 1897, woodcut.

Meanwhile, Stendhal had launched the fashion for comparisons between painters and musicians, which produced a whole stream of such pairings. The most popular, although not necessarily the most convincing, were the pairing of Mozart, after Raphael and Beethoven with Michelangelo. Romanticism promoted music to the rank of a leading art form, a model of expressivity and spirituality. Walter Pater, and before him Schopenhauer, claimed that ‘all art aspires constantly to the condition of music.’21 The much-debated opposition between instrumental or ‘pure’ music (Hanslick) and vocal or thematic music (defended by Hugo Wolf22) influenced the visual arts in addin...