- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

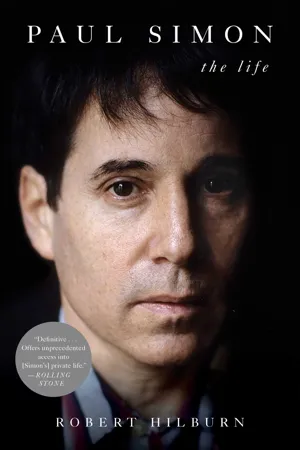

Acclaimed music writer Robert Hilburn’s “epic” and “definitive” (Rolling Stone) biography of music icon Paul Simon, written with Simon’s full participation—but without his editorial control—that “reminds us how titanic this musician is” (The Washington Post).

For more than fifty years, Paul Simon has spoken to us in songs about alienation, doubt, resilience, and empathy in ways that have established him as one of the most beloved artists in American pop music history. Songs like “The Sound of Silence,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Still Crazy After All These Years,” and “Graceland” have moved beyond the sales charts and into our cultural consciousness. But Simon is a deeply private person who has said he will not write an autobiography or talk to biographers. Finally, however, he has opened up for Robert Hilburn—for more than one hundred hours of interviews—in this “brilliant and entertaining portrait of Simon that will likely be the definitive biography” (Publishers Weekly, starred review).

Over the course of three years, Hilburn conducted in-depth interviews with scores of Paul Simon’s friends, family, colleagues, and others—including ex-wives Carrie Fisher and Peggy Harper, who spoke for the first time—and even penetrated the inner circle of Simon’s long-reclusive muse, Kathy Chitty. The result is a deeply human account of the challenges and sacrifices of a life in music at the highest level. In the process, Hilburn documents Simon’s search for artistry and his constant struggle to protect that artistry against distractions—fame, marriage, divorce, drugs, record company interference, rejection, and insecurity—that have derailed so many great pop figures.

“As engaging as a lively American tune” (People), Paul Simon is a “straight-shooting tour de force…that does thorough justice to this American prophet and pop star” (USA TODAY, four out of four stars). “Read it if you like Simon; read it if you want to discover how talent unfolds itself” (Stephen King).

For more than fifty years, Paul Simon has spoken to us in songs about alienation, doubt, resilience, and empathy in ways that have established him as one of the most beloved artists in American pop music history. Songs like “The Sound of Silence,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Still Crazy After All These Years,” and “Graceland” have moved beyond the sales charts and into our cultural consciousness. But Simon is a deeply private person who has said he will not write an autobiography or talk to biographers. Finally, however, he has opened up for Robert Hilburn—for more than one hundred hours of interviews—in this “brilliant and entertaining portrait of Simon that will likely be the definitive biography” (Publishers Weekly, starred review).

Over the course of three years, Hilburn conducted in-depth interviews with scores of Paul Simon’s friends, family, colleagues, and others—including ex-wives Carrie Fisher and Peggy Harper, who spoke for the first time—and even penetrated the inner circle of Simon’s long-reclusive muse, Kathy Chitty. The result is a deeply human account of the challenges and sacrifices of a life in music at the highest level. In the process, Hilburn documents Simon’s search for artistry and his constant struggle to protect that artistry against distractions—fame, marriage, divorce, drugs, record company interference, rejection, and insecurity—that have derailed so many great pop figures.

“As engaging as a lively American tune” (People), Paul Simon is a “straight-shooting tour de force…that does thorough justice to this American prophet and pop star” (USA TODAY, four out of four stars). “Read it if you like Simon; read it if you want to discover how talent unfolds itself” (Stephen King).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

The Boxer

CHAPTER ONE

The first sound Paul Simon fell in love with was the crack of a baseball against a Louisville Slugger, preferably one swung by a member of his beloved New York Yankees. He could even tell you the moment: the summer of 1948 when, at age six, he sat down with his father to listen to his first baseball game on the radio. Lou Simon was a professional musician, and he was out a lot, especially in the evenings, so Paul loved any chance to spend time listening to the radio with him, regardless of the program.

But this time was special. Paul immediately got caught up in the excitement of the announcer’s voice (most notably, the ebullient Mel Allen) and the cheers of the Yankee Stadium crowd. He later became enthralled by the team’s illustrious history of legendary players and more World Series championships by far than any other franchise. His allegiance was so strong that when his grandfather Samuel Schulman took him to see the rival Brooklyn Dodgers play at Ebbets Field, Paul wore his Lone Ranger mask as a disguise—on the outside chance that if he ran into anyone he knew, he didn’t want them to think he was a Dodgers fan. The games had such a powerful effect on Paul’s mood that his mother had to listen in to the afternoon broadcasts to keep track of the score. If the Yankees lost, she knew there was no point in defrosting a steak, because Paul would be so upset he wouldn’t eat.

One thing Paul loved as much as the games themselves was the Topps baseball cards that came five to a package, along with a stick of bubble gum. Each card featured a color photo of a major leaguer on one side and the player’s game statistics and personal data on the other. Where most youngsters cared only about the batting or pitching stats, Paul focused on another piece of information: the player’s height. He knew by junior high school that his dream of playing for the Yankees was threatened by an issue that would haunt him for years: his size. Thumbing through the cards, he hoped to find players close to his own height to give him hope that he might indeed be able to play pro ball—if he just got a big growth spurt. Paul was around five feet tall at the time, and the shortest players he could find were Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto and Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Bobby Shantz, both five foot six.

Paul was still so short his senior year at Forest Hills High School that the baseball coach, Chester (Chet) Gusick, wouldn’t let him try out for the team until some of the other kids told him that Paul was a terrific player. Given a turn during batting practice, Paul made the team by hitting a home run. Despite his size, he batted over .300 and showed enough speed on the basepaths to be put in the leadoff spot in the batting order. He was even named to the league all-star team.

His greatest moment on the field came on May 13, 1958, with the Forest Hills Rangers trailing Bayside High by a run in the seventh inning. Paul was on third base when he noticed that the opposing pitcher was taking his full windup rather than pitching from the stretch. In that instant, he knew he had a chance to pull off one of baseball’s rarest and most exciting plays: stealing home. After getting the go-ahead from the coach, he took off as soon as the pitcher began his windup, and he slid across home plate just before the catcher applied the tag. Two innings later Paul contributed a bunt single to a four-run rally, which gave the Rangers a 7–3 win. But it was the steal that Paul would always remember. The headline in the Long Island Press said it all: “Simon Steals Home.” Sixty years on, a reproduction of the article is still displayed on a wall in Paul’s Manhattan office.

As it turned out, that steal was Paul’s last hurrah in baseball. When he tried out for the team at Queens College the following year, he knew after a few days of practice that there was no way he could compete against college pitchers, many of whom stood over six feet and threw with blazing speed. “The coach didn’t say anything, but I realized I was done,” Simon said. The moment wasn’t as devastating as it might have been, because Paul, by then, was consumed by a new sound: rock ’n’ roll.

Simon was not a child prodigy who astounded the rest of the family by playing sonatas on the piano at age three or writing dazzling poetry in his grade-school notebooks, his lifelong pal Bobby Susser pointed out. Paul had little interest in pop music as a child—certainly not the bland mainstream hits that were on the radio in the early 1950s. Even when his father tried to stir an interest in music with piano lessons, Paul resisted.

It wasn’t until the summer of 1954 that Paul, quite by accident, discovered his calling. As he did each game day, Paul sat down to listen to the Yankees on WINS. But on this day, the radio was tuned to another station: one playing the mainstream pop that bored him. As he reached to change the station, the DJ’s remark caught his ear. “He said something like, ‘This record is becoming a hit around the country, but I think it’s the worst record I’ve ever heard,’ ” Paul said a half century later. “Now, that was interesting—the worst record he’d ever heard. I had never heard anyone say that on the radio.” Sure enough, DJs were always praising records; there was no point in saying they didn’t like the next record because it might encourage listeners to tune out. Curious, Paul kept listening and soon heard a doo-wop expression of romantic infatuation by the Crows, a black rhythm-and-blues group from Harlem. Called “Gee,” the record felt fresh and alive. The song’s giddy lyrics (supposedly written in ten minutes) were catchy, and the group’s lead singer, Daniel (Sonny) Norton, moved up and down the notes with acrobatic ease.

“Ohh-ohh-ohh, gee-ee,” Simon recalled, singing one of the tune’s opening lines. “The record sounded so young, and it had a good beat, and the lyrics were simple. I even liked the name of the group: the Crows. Immediately, I felt, ‘That’s my music.’ It’s not those big ballads you heard on the radio back then: things like ‘See the pyramids, along the Nile,’ and all that.”

Wanting more of this new sound, Paul turned the dial endlessly in the coming weeks, hoping to find a station that played it regularly. As it turned out, he didn’t need to turn the dial at all. Alan Freed, a disc jockey who had popularized rock ’n’ roll in Cleveland earlier in the 1950s, moved his show to WINS, the Yankees station, in September 1954. Paul began looking forward to Freed’s show with the same passion as the ball games. When he would say again and again over the years that he knew he wanted to be in music by the time he was thirteen, Paul was speaking about the lure of “Gee” and a handful of other extraordinary R&B songs he heard that year, including the Moonglows’ “Sincerely” and the Penguins’ “Earth Angel.”

He got so caught up in the sounds that he asked his father to buy him a Stadium acoustic guitar for his thirteenth birthday that October and teach him some chords. Lou, who played upright bass, didn’t care for this primitive doo-wop sound, but he was pleased his son was finally interested in some kind of music; it’d be a good hobby, ideally leading him to something more sophisticated, such as jazz or Broadway show tunes.

It wasn’t long before Paul wanted more. To capture the harmonies of the records, he needed another singer. He didn’t need to look far. Thanks to one of life’s wondrous twists of fate, Paul’s parents had moved into a home just two blocks from a family named Garfunkel.

Paul Fredric Simon was born on October 13, 1941, at Beth Israel Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, but the Garden State ties were short-lived. Before his second birthday, he was calling New York home—which is where fate comes in. Belle’s brother’s wife, Goldie, died on May 23, 1943, and Belle’s brother Lee Schulman, a graphic artist who lived in Kew Gardens Hills, Queens, asked her to stay with him for a while to help care for his young son, Jerry. Belle’s family was tight knit, and she didn’t hesitate, even though it meant that she and Paul would have to leave Lou behind temporarily in Newark, where he played bass on a music show that aired weekday mornings on radio station WAAT.

The move not only introduced the Simons to Kew Gardens Hills, which would be Paul’s home for the next two decades, but it also led him to his future singing partner. Lee Schulman lived on Seventy-Second Avenue, almost directly across the street from Jack and Rose Garfunkel, whose second son, Arthur, was born on November 5, 1941. Despite the proximity, there is no evidence that the children actually met until grammar school.

Kew Gardens Hills—adjacent to prestigious Forest Hills, home for years of the US Open tennis championship—was in the 1940s a picturesque middle-class neighborhood. To young couples, the rows of mostly attached or semiattached houses represented a coveted piece of the American dream. Yet there were moments of anxiety for Paul, including living in a house where a mother had just died and not having his father around except for occasional weekends. Looking back years later, Paul wondered if his long history of violent dreams wasn’t triggered by living in his uncle’s home. The dreams, which would become more frequent over the years, could be very gory and upsetting. Without ever finding a reason for them, he simply learned to accept them.

After a year or so of separation, Lou rejoined the family when he got a job playing bass on radio station WOR in New York. He and Belle rented an attached house at 141-04 Seventy-First Street, close enough to the Schulmans for Belle to walk over there to watch Jerry until Lee got home from work. “It was happy times again,” Paul said. “Dad was back.”

When the Simons’ second son, Edward, was born on December 14, 1945, Lou and Belle needed a larger place, and they bought their first home: an attached residence at 137-62 Seventieth Road. By this time, Belle no longer needed to help her brother because Lee had remarried. To make the Simon family reunion even more joyous at the time of Eddie’s birth, the nation was still caught up in celebrating the end of World War II.

In a photo of Paul standing in the driveway of the family’s two-story house—the same driveway where as a youngster Paul and his dad often played catch—the Simon house looks identical to the one next to it. If the camera had provided a wider view, we would see that every other house up and down the long block looked the same. This cookie-cutter approach caused Lou endless frustration. “My father used to drive into the wrong driveway all the time,” Paul said. The story is special to Paul because it’s one of the few times he heard his mother or father complain about anything. Paul’s acquaintances from those days agree: this was a loving family.

“Paul was such a good, happy baby,” said Beverly Wax, whose husband, Harold, played accordion at the Newark radio station with Lou, and who first saw Paul when he was just a week old. “He fit in perfectly with his mom and dad, who were the nicest people you could find.” Paul and Eddie enjoyed each other’s company so much that they eventually gave up their separate bedrooms to share what was Paul’s upstairs room. It was a bonding that continued into adulthood, when Eddie would eventually comanage his brother. “We all know people whose lives have been very much molded by trauma, but that wasn’t our case,” Eddie said. “If you were ever in trouble, my mom and dad would help you. They made it so you were not fearful. In his career, Paul’s never been afraid to move on.”

Fittingly, Paul’s parents met through music. While on a weekend getaway in the Berkshires with girlfriends in 1937, Belle Schulman met Lou, who was playing in a band. They began a courtship that led to their marriage on September 15 of the following year in Newark. Both were native-born Americans, children of immigrants who had come to the United States separately between 1882 and 1909. Paul’s father’s family came from small towns in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in territory that is now part of Ukraine, while Paul’s mother’s family came from small towns—shtetlach in Yiddish—in Lithuania, which was then a province of Imperial Russia.

Paul’s paternal grandfather was born Pinkas Seeman, but he changed his first name to Paul before arriving in the United States in 1909, and he adopted the last name Simon before Paul’s father was born in 1916. Seeman/Simon was a successful tailor until he lost his business in the Great Depression, and subsequently opened a small deli in Newark. Belle’s father, Samuel Schulman, was for years a commissioned salesman at Phillips Clothing Company, a retail store in Manhattan. His future wife, Ettie Marcus, worked across the street in a clothing accessories store. They were married in 1902, and Paul’s mother was born in 1909, the last of two sons and two daughters in the family.

While Paul’s grandparents immigrated to the United States primarily in search of a better life, they were fortunate to leave Eastern Europe before anti-Semitism led to the butchery of the Holocaust. George Schulman, Paul’s cousin, traced his family roots to Lithuania, where he said bullet holes in a churchyard wall in the town of Trishik were still visible. In the early summer of 1941, Nazi SS troops rounded up seventy to eighty Jews, almost certainly including some of Paul’s relatives, and opened fire. Soon the Nazis moved through other cities, including Kalvarija and Vilkaviskis, where more relatives lived. Jewish men were typically rounded up and shot, and women and children were murdered within weeks.

In the safety of America, Lou, under the stage name Lee Simms, led his own dance band every Thursday afternoon for nearly twenty-five years at the landmark Roseland Ballroom in Manhattan’s theater district. He also did periodic dates with Lester Lanin, the society bandleader whose elegant dance music was featured at hundreds of parties for some of the world’s wealthiest and most celebrated people, from actress Grace Kelly’s engagement to Prince Rainier III of Monaco in 1956 to the sixtieth birthday of Queen Elizabeth II in 1986. On top of it all, Lou also played several seasons in the house orchestra for CBS-TV shows hosted by personalities such as Jackie Gleason, Arthur Godfrey, and Garry Moore. Paul and the rest of the family would watch the programs at home, hoping to get a glimpse of Dad.

That résumé, however, made Lou’s musical world seem more glamorous than it was. Aside from the freelance dates at CBS, he spent most of his time in music performing at social gatherings, weddings, and bar mitzvahs. The jobs didn’t pay all that much, and they were irregular, forcing Lou to spend almost as many hours lining up gigs as playing them. The stress may have contributed to his lifelong health problems, including numerous heart attacks.

One of Paul’s favorite childhood memories was accompanying his father to the radio station when he was around four and watching a live broadcast. As the musicians played, they read the notes from sheet music on a stand and then tossed away the top page to see the next one. Paul thought one of the musicians had thrown the paper by mistake, so he raced over, picked up the sheet music, and placed it back on the stand, causing everyone in the room to break out in laughter—a moment so embarrassing that Paul recalled his discomfort decades later.

While Paul didn’t respond to the piano lessons, Eddie enjoyed playing classical piano, especially when his father accompanied him on bass. What impressed Eddie was how his dad, even in the informality of their home, took the music seriously. There was nothing casual about his playing: he played in perfect tune, from the start of the duet to the end, and Eddie thinks Paul picked up on that dedication. Music was something to be treated with respect. Bobby Susser, his friend, also believes Paul embraced Lou’s dedication. “Lou always wanted to be a notch or two above the rest no matter what he was doing, and he wanted the same for Paul. With regard to music, there was no such thing as mastering it. The goal was always to get better—never settle.”

The Simon home on Seventieth Road was in such a new development that construction of the local elementary school, PS 164, wasn’t finished until Paul was ready for the third grade. That meant he attended kindergarten at PS 117 in the fall of 1946. That school was in Jamaica, Queens, just two miles away across the Grand Central Parkway, but any separation from his mother was difficult. When the bus pulled up for the first day of school, Paul refused to get on unless Belle came with him. She gamely climbed aboard for the short ride along Main Street.

Things went fine that day, and Paul stepped on the bus by himself the following morning. In the coming months, he adjusted well to school, and he received high praise from his teachers during his three years there—though one of them would later describe him as especially sensitive, noting that he tended to cry easily. Belle, too, remembered Paul’s sensitivity when he befriended a neighborhood boy with Down syndrome and accompanying speech problems. On his way home from grade school, Paul would often stop by the boy’s house and play catch with him. It got to where the boy would start shouting, “Paul! Paul!” whenever he saw Paul coming down the street. That was, Belle said, the first word the youngster learned.

Simon also had a tremendous imagination, said Beverly Wax, the family friend from the New Jersey days. “He was always making up games or stories. Even when he was little, I thought that he might become a writer. He was always observing things and then describing them in an original, thoughtful way. Even when he was ten or eleven, he spoke like an adult.”

Helene Schwartz Kenvin, who also attended PS 117 and PS 164, recalls Paul being well liked. She and Paulie, as she called him, were class president and vice president, respectively, for several semesters. She also believes Paul benefited from the high academic standards of his grade school, which required students to complete a three-year study program of the nation’s historical documents, including the Bill of Rights, the Gettysburg Address, and Patrick Henry’s speech to the House of Burgesses—papers crammed with complex legal and philosophical language. Kenvin said, “Can you imagine nine-year-old children reciting ‘on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent . . . on a land rent with civil feuds’—from Daniel Webster’s reply to Senator Robert Y. Hayne—and understanding what they were saying? We all became exceptionally literate, and I think that it shows in the poetry of Paulie’s lyrics.”

Despite getting high marks, Paul’s teachers sometimes mentioned to his mother that he could do even better if he paid attention rather than stare out the classroom window and daydream. But Belle, herself a popular elementary schoolteacher for years, defended her son. “I think she understood that the ones who are looking out the window are sometimes your best students, not the ones who always raise their hand and want attention,” Paul said. “I always thought that was embarrassing. I wanted attention, too, but I didn’t want to be seen as wanting it. I wanted it to come naturally, by doing something that warranted it, rather than me manipulating people to look at me.” Onstage years later, Paul tended to follow that same guideline. He wasn’t interested in being a showman; all he cared about was playing the music.

Whatever his manner in the classroom, Paul was placed into a special progress program at Parsons Junior High that enabled him to go through the school in two years rather than the normal three. If Paul needed any further assurance about his own intelligence, the word passed down in his family was that Lou, during high school, registered the highest IQ score in the state of New Jersey. “I went to two Ivy League universities, and I’ve often said I never met any group of people as smart as the kids I knew when I was a child,” s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Prologue

- Part One: The Boxer

- Part Two: The Sound of Silence

- Part Three: Bridge Over Troubled Water

- Part Four: Still Crazy After All These Years

- Part Five: Graceland

- Part Six: Questions for the Angels

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- Photo Credits

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Paul Simon by Robert Hilburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.