- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

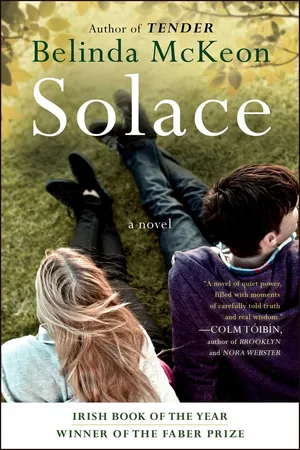

“A novel of quiet power, filled with moments of carefully told truth and real wisdom” (Colm Tóibín, author of Brooklyn and Long Island), about a father and son thrown together by tragedy—from the author of Tender.

Set in an Ireland that catapulted into wealth at the end of the twentieth century and then suffered a swift economic decline, Belinda McKeon’s Solace is an extraordinarily accomplished first novel about the conflicting values of the old and young generations and the stubborn, heartbreaking habits that mute the language of love.

Tom and Mark Casey are a father and son on a collision course, two men who have always struggled to be at ease with one another. Tom is a farmer in the Irish midlands, the descendant of men who have farmed the same land for generations. Mark, his only son, is a doctoral student in Dublin, writing his dissertation on the nineteenth-century novelist Maria Edgeworth, who spent her life on her family estate, not far from the Casey farm. To his father, who needs help baling the hay and ploughing the fields, Mark’s academic pursuit isn’t work at all. Then, at a party in Dublin, Mark meets Joanne Lynch, a lawyer in training whom he finds irresistible. She also happens to be the daughter of a man who once spectacularly wronged Mark’s father, and whose betrayal Tom has remembered every single day for twenty years.

After the lightning strike of tragedy, Tom and Mark are left with grief neither can share or fully acknowledge. Not even the magnitude of their mutual loss can alter the habit of silence. “A story told with clear-eyed compassion and quiet intelligence about what it is to grow up and grow away, about the difference between ‘here’ and ‘home.’ This is a lovely debut” (Anne Enright, Man Booker Prize–winning author of The Gathering).

Set in an Ireland that catapulted into wealth at the end of the twentieth century and then suffered a swift economic decline, Belinda McKeon’s Solace is an extraordinarily accomplished first novel about the conflicting values of the old and young generations and the stubborn, heartbreaking habits that mute the language of love.

Tom and Mark Casey are a father and son on a collision course, two men who have always struggled to be at ease with one another. Tom is a farmer in the Irish midlands, the descendant of men who have farmed the same land for generations. Mark, his only son, is a doctoral student in Dublin, writing his dissertation on the nineteenth-century novelist Maria Edgeworth, who spent her life on her family estate, not far from the Casey farm. To his father, who needs help baling the hay and ploughing the fields, Mark’s academic pursuit isn’t work at all. Then, at a party in Dublin, Mark meets Joanne Lynch, a lawyer in training whom he finds irresistible. She also happens to be the daughter of a man who once spectacularly wronged Mark’s father, and whose betrayal Tom has remembered every single day for twenty years.

After the lightning strike of tragedy, Tom and Mark are left with grief neither can share or fully acknowledge. Not even the magnitude of their mutual loss can alter the habit of silence. “A story told with clear-eyed compassion and quiet intelligence about what it is to grow up and grow away, about the difference between ‘here’ and ‘home.’ This is a lovely debut” (Anne Enright, Man Booker Prize–winning author of The Gathering).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Everything was plastic in the beer garden. Plastic chairs. Plastic tables. Plastic pint glasses. The barbecue food tasted plastic—as, Mark noticed, did the beer. It was his second pint, or his third; he couldn’t remember. It didn’t matter. It was a rare hot Saturday in a summer that was already halfway through, and there was no point in complaining.

The place was mobbed. Teenagers from the flats. Pillheads still going from the night before. The rugby fans, spilling in after the match. The weekend crowd: groups of couples gabbing at each other around big tables, and guys in short-sleeved shirts and boot-cut jeans, and women with shopping bags flapping at their sides like huge broken wings.

Mark was here because he had not been able to force himself to be where he was meant to be, which was in his carrel in the college library, finishing the chapter that was due on his thesis supervisor’s desk on Monday morning. He had a chapter title—“Patronizing the Place”—and he knew he wanted to do something on Edgeworth and her relationship to the local people she wrote about, but that, and a clutch of increasingly frenzied notes, was pretty much all he had. This was to be his second chapter. His introduction he had written during the first months of the PhD, in a white heat of interest he could now hardly believe he had ever achieved, and his first chapter he had wrenched out painfully, piecemeal, over the course of the following two years. Even by then he had begun to wonder about the wisdom of the idea: a thesis on Maria Edgeworth, the nineteenth-century novelist who had lived most of her life in the manor just ten minutes away from his childhood home. Even by then he had questioned his ability to see the thing through. By now, he was almost in despair about the thesis, prone to moments of wishing that Edgeworth had actually thrown herself out of the upstairs window on which she had perched, at the age of five, telling the maid who pulled her back in how very unhappy she was; there were days, now, when Mark thought he knew how she had felt.

He spent his time trudging through the books on education Edgeworth had written with her father, or trying to decipher her wiry, cross-hatched handwriting on yellowed pages in the National Library. Or looking for his theories in her fiction. Scouring the novels and the tales for proof of the argument he had once so firmly believed he could make. He could see, now, only naïveté in the conviction with which he had chosen Edgeworth as his subject, in his confidence that a local connection would somehow give his research some edge, some particular authority. Because what did it add, to know Edgeworthstown as a real town, as something more than a place-name in a biography? So what if he had walked its main street—its only street—a thousand times; if, as a kid, he had parked his bike against the walls of the old coach house where she had once taught; if, as a teenager, he had gone knacker drinking in the graveyard where she and her family had their tomb? So he knew how the old house looked inside: what of it? It was no longer the old house in any case, had not been for decades; the Sisters of Mercy had long since gutted it and turned it into the hospital where Mark’s mother had been a nurse before he and his sister were born, and once again when they were settled at school. They were no use to his thesis, Mark’s memories of those evenings driving up to the manor with his father, to collect his mother after her shift, of waiting for her in the high-ceilinged hall. And anyway, he remembered little: the phlegmy splutters of the old people doddering in the shadows; the nuns, in their thick-soled shoes, moving noiselessly across the parquet floors. The sound of a cry, sometimes, that maybe was only someone caught up in a dream.

None of this, Mark had quickly discovered, was valuable at all. It was nothing better than local gossip, and it could not help him get to the core of his central argument, if he could even remember what his central argument was. “Promising”: that was how his supervisor, McCarthy, had described it at first; later, “promising” was downgraded to “interesting,” and later still “interesting” became “tentative,” and Mark was not eager to know what McCarthy’s current assessment was. But he had to get him the chapter; without the chapter, he risked losing his funding, that complicated marriage of university, departmental and government money which, put together, allowed him to live a little more comfortably than he suspected a graduate student in Anglo-Irish literature should. Getting it for another year depended on getting McCarthy’s signature on the renewal form—which could happen, McCarthy had warned Mark, only if the second chapter arrived before McCarthy left for his annual month in West Cork. And, as Mark watched his housemate, Mossy, return from the bar with yet another round, he knew the chances of securing McCarthy’s autograph were fading fast.

Walking with Mossy was Niall Nagle. Mark had known him when they were undergrads in Trinity—he was the guy who was always sitting, yammering, on the desk of some female business student in the library—but he had barely seen him since, and he was surprised to see him now, and to hear that he and Mossy were deep in conversation about the rugby. Nagle must have just come from the match: he was wearing the polo shirt with a bank’s name plastered across the chest—a chest that was looking, these days, almost as generous as those of the girls whose desks he had haunted in the Lecky. With a paunch to match. He was telling Mossy something about backs, how hard they had to work, how much brainpower had to go into every move. “Contrary to popular impression,” he said, and took a swig from his bottle of Miller. He had always been like that in college; a vocabulary like a radio pundit. How did Mossy still know this guy? How had they stayed in touch? And since when did Mossy care anything for rugby? He had always, like Mark, been contentedly indifferent to sports. It might matter to him fiercely whenever Clare reached an All-Ireland final, but everything else he ignored. Mark, meanwhile, came from a county where the teams barely lasted a month into the season, so it was a rare Sunday that Micheál Ó Muircheartaigh’s commentary—like a cattle auctioneer let loose in Croke Park—became part of the soundtrack. But now here was Mossy, talking about this match as intensely as though he had been in the dugout in Lansdowne Road.

To Mark, it was a mystery. But then so much about Mossy was, even after six years of sharing a place with him. The people in Mossy’s life were a mixed bag, seduced and snuck and stolen from the many lives Mossy seemed, already, to have passed through. A year ago he had been writing a master’s thesis on de Valera, quickly abandoned; a year before that he had been temping in a borrowed suit at the Stock Exchange on Anglesea Street; a few years before that, he had been backpacking in an Argentina where money was suddenly worth nothing. And now he was working in a self-proclaimed arthouse DVD store on George’s Street, shelving cases and calling in late returns and coming home with subtitled films and stories of the customers he dealt with: the widows and widowers in need of something to get them through the day; the new couples trying to impress each other; the Indian guys looking for Ben Affleck films; the porn addicts, some of them showing up twice or three times in the same day; the foreigners, looking for relief from the English language; the junkies, looking for a hidden corner.

“I’m surprised to see you here on a day like this, Casey,” Nagle shouted from across the table. He was smirking, lighting himself a cigarette. “Don’t you have hay to make or something like that?” he said. “Cows to milk, turf to stack, whatever it is you do down the sticks when the summer finally cops itself the fuck on?”

This was how Nagle had always addressed him back in Trinity; the same loud amusement at the idea of someone his own age, in his own college, choosing to spend so many of his weekends on a farm. There were rugby matches to go to. Rugby bars to cram into. Rugby birds to pursue. What was Mark doing, driving tractors and testing cattle and shovelling shit-caked straw out of sheds? Nagle never understood, but he never seemed to tire of asking, either.

“Not this weekend,” Mark said now, but he knew it would not be enough for Nagle.

“Jesus, Casey, even when it’s lashing rain you seem to be down there fucking around at some animal or other. Sun’s splitting the stones today, and yet here you are, up to your balls in beer. What, did you finally get them off your back? What, did your old lad die?”

Beside Nagle, Mossy shook his head in laughing disapproval. “Nagle, you bollocks.”

Nagle affected a wide-eyed look, the only effect of which was to accentuate his jowls. “What? It’s a fair assumption. Isn’t it, Casey? I mean, Jesus, I’m basically not sure if I’ve ever seen you in the sunshine before.”

“Right, right,” Mark said, as drolly as he could.

“I mean, for a while there, back in college, I was starting to look for fangs on this guy,” Nagle said to Mossy. “No joke.”

“You’re some tool,” said Mossy, reaching for one of Nagle’s cigarettes. Mark could see Nagle noting this move as he inhaled, deciding to let it go as he blew the smoke out in a formless cloud.

“You ready for another?” Mark nodded to Mossy’s glass. It was only half-empty, but he wanted to get away. He took a long gulp of his own pint as though to justify the question.

Mossy nodded. “I’ll go with you,” he said. “I need smokes.”

“Fucking right you do, Flanagan,” Nagle said, snatching up his pack of Marlboros and turning his attention to the girls at the next table. “Beautiful day, ladies,” he said, to the back of one sleekly ponytailed head.

“Arsehole,” said Mossy, as they entered the cool darkness of the inside bar. In here, the place looked as it would at this time on any day, in any month of the year, a hard-chaw bar on a hard-chaw street in inner-city Dublin, full of life-pocked locals, all scowls and silences and sagging midriffs, all watching—they all seemed to be watching—as Mark and Mossy came in through the back door. But glancing up, Mark saw what they were actually watching: highlights of the rugby match on a huge television high on the wall. On the screen, a player was panting and pawing at his gumshield.

“When did everyone in this country start giving such a shit about rugby?”

Mossy shrugged. “Civilised times, man.”

The barman signalled to say he’d be over in a moment.

“I didn’t realise you still knew Nagle,” Mark said to Mossy, with more accusation in his tone than he’d intended. He cleared his throat. “What’s he up to these days?”

“Over in one of the big banks on Stephen’s Green. Doing well for himself. Doing something suss with other people’s money. The usual.”

“See much of him?”

“The odd time,” Mossy said. “Think whoever brought him in here today did a legger on him. He came up to me there at the bar like I was a brother of his back from the dead. Pure relief to see someone he could talk to.”

Mark looked around the bar. “Probably afraid one of this crowd would go at him with a dirty syringe.”

“No harm,” Mossy said. “Though they’d have a job ramming it into that neck.”

The barman came to them, and Mark ordered the drinks. “He’s still as obsessed with my old lad’s farm as he ever was.” He shook his head. “Prick.”

“Yeah,” Mossy said. “Though I have to say I was wondering the same thing myself.”

“Wondering what?”

“Well, y’know. This good weather. I mean, I was sure you’d be heading down home. I thought I’d be getting up to an empty house this morning.”

“I have work on,” Mark said, without looking at Mossy. “This deadline for McCarthy.”

“Decent of them to leave you at it for a change.”

“Five missed calls since yesterday evening.”

“Fuck.” Mossy whistled.

“Yeah.”

“Ah, man, that’s a hard old buzz. You didn’t chat them at all, no?”

“Ah yeah.” Mark shook his head. “I mean, I talked to my mother this morning. Told her the score. She understood. I said I’d be down Tuesday.”

“Good stuff.”

“Good stuff as long as this weather holds,” Mark said.

“Well,” Mossy said, with a wince, and then gestured apologetically over to the cigarette machine, as though it were an obligation he could not escape, as though he would much have preferred to stay at the bar with Mark, reassuring him about the weather, about his chapter, about parents and the things they expected their sons to do. But then, Mossy’s parents did not expect their son to do things. Mossy’s parents were busy with their own lives, with the friends they had, with the trips they took, with the visits from their children that they sweetly encouraged but would never demand.

“I’ll just get these,” Mossy said, and he was gone.

Mark settled closer in to the bar. The irritation he had felt at Nagle’s goading had faded, but still he was not keen to return to the beer garden, and to be alone with Nagle, even for the length of time it would take for Mossy to return from buying his cigarettes. What he wanted, he realised, was for Mossy to go out there alone and start up a conversation with Nagle, a conversation about anything, and for Mark to return to find the two of them absorbed in that subject, and to come in on it, and take part in it, mindlessly, for the rest of the evening, until the beer started to really take hold, until it no longer mattered what anyone said, because nothing could get at you.

On the phone that morning, his mother had spoken in the vague, terse sentences that meant, he knew, that his father was in the room. His father had never been one to talk on the phone, but that did not mean he relinquished his determination to know—and, as though by a sort of hypnosis, to control—what was being said and what was being agreed to at the other end of the line. Mark had seen it countless times: his mother, standing at the kitchen counter where the phone was kept, trying to get the conversation over with, while his father sat nearby, his chin pushed into his knuckles, his eyes roving the floor as he followed and weighed and dismantled every word—the words he could hear and the words at which he could only guess. It was a harmless charade, really, comical half of the time, because half of the time his father got it all arseways: the imagined details, the assumed scenarios. He was bored, Mark knew; he craved news, craved some new narrative to add to his day, and if, eavesdropping on Mark’s mother’s phone calls, he couldn’t glean that thing ready-made, he would invent it for himself.

And his father would long since have invented his own reasons for Mark’s decision to stay in Dublin that weekend despite the unfolding, on the farm, of the exact science they both knew so well: this was the second day with clear skies and temperatures above the mid-twenties, the second day in what was forecast to be a five-day spell, and it was a July day, so the meadows would be at their readiest, the ground would be baked firm. It was the day to cut, and tomorrow was the day to bale, and the next day was the day to gather, and without Mark, none of this could be done quickly or easily. And yet Mark was staying away. And as the explanation for that fact, his father would either settle on something depressingly wrong—that it was something to do with a woman—or depressingly right: that he was up shit creek with his college work. Though his father would add to the actual problem an extra dimension of crisis: Mark, he would decide, would be on the verge of losing not just his funding, but his place on the programme, his right to continue with his thesis, to walk through Front Arch and set foot on campus at all. He would be thrown out. He would be disgraced in the eyes of Dublin. And the eyes of Dublin would be nothing compared to the eyes of home.

Mark knew that his PhD work, and any mention of it, held a power over both his parents; a power that was often very convenient for him. In the face of what his father insisted on calling Mark’s “studies,” they became as quiet and uneasy as though they had opened a solicitor’s letter or answered the door to a guard. It was to them something alien, unfathomable, something utterly intimidating; a degree beyond a degree, an essay that would take years of their son’s life, that would turn him, at the end of all, into something just as alien and unfathomable: a university lecturer, a writer of books without storylines, papers without news.

The fact of his mother’s having nursed at the manor house had formed a thread of delighted connection between them, for a while. That first year of his thesis work, when he was still in love with the idea of writing about Edgeworth, his mother had talked to him about the old house every weekend he came home; she had taken him to see the place, arranged for the caretaker to show him the parts that had been least changed since the Edgeworths had sold it in the thirties. But there were hardly any such parts left, in truth. A surviving cornice, high in the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Prologue

- Part One

- Part Two

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

- ‘Tender’ Excerpt

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Solace by Belinda McKeon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.