![]()

1

A Cause Worth Dying For

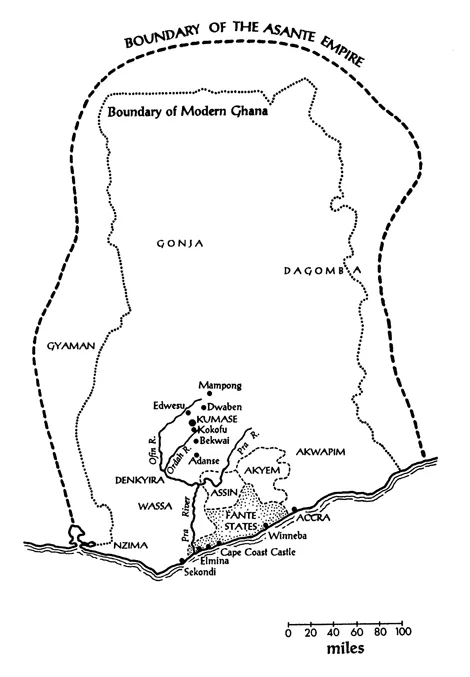

AT THE START OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, WHEN ASANTE AND British interests first collided, the Asante Empire was at its height. Incomparably the most powerful state in West Africa, it ruled over more than three million people throughout what is now Ghana (then called the Gold Coast). This was more than half as many people as there were in the United States at that time and more than one quarter as many as the population of Britain, which was only eleven million in 1801. In area the empire was larger than England, Wales, and Scotland combined or, from an American perspective, the state of Wyoming. From south to north it stretched for over four hundred miles, and it dominated nearly five hundred miles of coastline.

If one could have flown over this large area at that time, the dominant impression would have been a seemingly endless expanse of dense tropical forest, only occasionally broken by clearings for a few large towns, smaller villages, and widely scattered plantations. One would see little to suggest the presence of the complex civilization that the Asante leaders had developed over the preceding two hundred years by military conquests that gave them dominion over defeated peoples, many of whom were forced into slavery. During the first half of the eighteenth century, the Asante armies fought and won over twenty major battles that extended their empire to include all of present-day Ghana. These were anything but bloodless victories, and this remarkable success could not have been achieved unless a very large number of Asante men and women believed that their empire was worth dying for.

Great states had existed in West Africa for centuries before the Asante Empire—or Greater Asante, as historians now prefer to call it—came into being. Far to the east of modern Ghana, the ancient kingdom of Ghana flourished for about a thousand years before it collapsed and disappeared in the middle of the thirteenth century. Its capital city of Kumbi Saleh, some one hundred miles north of modern Bamako, was the largest yet seen in West Africa, having about fifteen thousand people. Ghana owed its greatness to its army of two hundred thousand men, whose iron-tipped spears allowed them to exact tribute and collect taxes from smaller states and chiefs over much of the western Sudan. Ghana also maintained trade routes north to the Arab world, and it began West Africa’s flourishing trade in gold. Arab visitors raved about the wealth and elegance of the court, mentioning such extravagances as royal guard dogs wearing gold and silver collars and a thousand royal horses with silken halters that slept on carpets attended by three men for each horse.1

Ghana was succeeded by many other states in the western Sudan, the greatest being Mali, which remained powerful until sometime after 1400 A.D. Farther to the east the Songhay Empire arose, and directly to the north of the Asante were the Mossi states. All of these states emerged in the savanna zone north of the great forest belt that covered the land closer to the sea. Free of the tsetse fly of the forest area, horses thrived there and trade flourished. Contact with the Arab world of merchants and scholars enriched these African states as well. The kingdoms of the southern forests were smaller in size and less opulent, but when the earliest Portuguese traders came to the Gold Coast in the 147Os, they found surprisingly regal men ready to trade with them shrewdly and with dignity. For example, at their new trading post of Elmina, they met a king whose jewels, brocaded jacket, and elegant manners, combined with his shrewdness, fairness, and good judgment, made a highly favorable impression.

Along the coast and just inland from Elmina lay numerous kingdoms of Akan- or Twi-speaking peoples, whose land contained many of the richest gold deposits in the world. This gold and Akan proximity to the European traders’ guns and gunpowder would soon give them a powerful advantage over the older and previously more powerful states to the north, which lacked ready access to firearms. These Akan people shared similar religious beliefs and governmental practices and were excellent farmers and skilled cattlemen despite the great heat and humidity. They manufactured many tradable goods, from cotton cloth to spears and fishhooks, and were highly accomplished gold miners. They also kept slaves, most of whom came to them from the north in return for gold. The abundance of these two sources of wealth—slaves and gold—would bring more and more Europeans to the area until the British achieved a monopoly on trade and finally conquered the Asante.

The tropical forest zone of the Gold Coast has two distinct rainy seasons, May-June and September-October, when torrents of rain flood the rivers and create almost impassable mud. The temperature often reaches 90°F, with humidity reaching 90 percent. In addition to several large rivers—the Tano, Pra, and Volta—the entire area is cut by innumerable streams. The Asante homeland is wet, luxuriant forest, so dark in many places that there is not enough light to read by. The only dry period is December-January when dry winds blow south from the Sahara and nighttime temperatures fall into the sixties. When the rains begin again in February and March, hail the size of musket balls is not uncommon.

The heartland of the Asante people was a forested area centered some one hundred fifty miles from the coast. At the end of the seventeenth century, there were two great powers in the forest, the kingdom of Akwamu to the southeast of the Asante and the kingdom of Denkyira to the southwest. Denkyira possessed the richest veins of gold in the region, dominated the coastal trade, and held the Asante as a tributary state until 1701, when, shortly after they first came to the attention of the Portuguese, the Asante defeated the Denkyira in battle. The leader of the Asante at that time was Osei Tutu, who had brought a number of smaller chiefdoms together by conquest and had attracted other immigrants through the appeal of his governance. The Asante, like other Akan groups, made stools the symbols of political authority Now each chief was made to bury his personal stool while Osei Tutu and his legendary priest, Anokye, gave the kingdom new unity by conjuring down from the sky, as Asante tradition has it, a Golden Stool said to contain the soul or spirit of the entire nation. Whatever legerdemain may have been involved, the idea was a brilliant success. The stool remains a powerful symbol of Asante unity to this day.

Armed with a new sense of national unity, the Asante were ready to break their economic dependence on the Denkyira with newly acquired guns supplied by the Dutch who believed that the Denkyira were thwarting their trade with tribes farther north. Aware that the Asante were restive, the Denkyira king attempted to force them into a premature attack by raping one of Osei Tutu’s favorite wives, who was paying a courtesy visit to the Denkyira court. Incensed by this calculatedly public insult, Osei Tutu sent his forces to battle in 1698, but it was not until 1701, when other kingdoms tributary to the Denkyira turned against them, that the Asante finally won, beginning the series of conquests that gave them preeminence over the Gold Coast.2

The origins of the Asante people are unknown. The Asante themselves say that they “came forth from the ground very long ago” somewhere in the southern part of the rain forest.3 Their culture probably developed from small bands of hunters, gatherers, and farmers, who have left fragments of stone axes and pottery throughout the forest zone. Sometime during the first millennium A.D., iron working was introduced to the area from the north. Many other influences were to follow. Before the Asante emerged as a kingdom under Osei Tutu, groups of related people must have migrated through the forest zone for hundreds of years. Lineages expanded and broke up as people quarreled or needed more land. Larger chiefdoms fled from their enemies, and new people migrated into the area. Early in the nineteenth century an English visitor to the Asante capital was surprised to learn that the Asante believed the British were so quarrelsome that they chose to live in wheeled houses in order to escape from their angry neighbors.4 This Asante perception mirrored their own past.

From 1300 to 1500 A.D., a prolonged drought in the savanna of the West Sudan drove many thousands of people to the well-watered forest zone where they mingled with the Akan speakers already there. Archeological finds show that they lived in thatchroofed, mud-walled houses, each with its own cistern, built around central courtyards. They farmed, raised cattle, sheep, and goats, and hunted game, especially antelope. In addition to antelope, elephants, leopards, and lions, all of which had value to the Asante for meat, ivory, and hides, the nearby forests were home to innumerable baboons and other monkeys, hyenas, civet cats, anteaters, sloths, wild boar, and porcupine. Tsetse fly-borne disease must have been less of a problem than it became later, because the Asante had horses in earlier times. In addition to having brass foundries and iron smelters, some of the larger towns manufactured textiles using the same spindle whorls used in Ghana today. They left behind many beads, ivory carvings, tobacco pipes, and stone or ceramic weights, presumably for weighing gold dust.5

With the Asante conquest of the Denkyira, the dynamics of the Gold Coast changed radically. The Asante now had access to the European traders at the coast, and with the rich Denkyira gold deposits they could purchase more slaves to work in their mines, cultivate their fields, and serve in their armies. Their gold also allowed them to purchase the guns they needed to defeat other kingdoms, and this they did with remarkable success. By 1750 they had defeated and largely incorporated into their empire nearly twenty kingdoms, including the Gonja and Dagomba of the savanna lands well to the north of metropolitan Asante. Welding these subject peoples into a relatively peaceful and subservient empire required great statesmanship, but the Asante also used force against conquered people when that was thought necessary.

Most of these conquests were directed by Osei Tutu’s successor, Opoku Ware, after his death in 1719. Opoku Ware’s thirty-year rule led to a remarkable expansion of the Asante Empire, more extensive than that brought about by any previous or succeeding king. In 1766 John Hippisley, the governor of the British trading company at Cape Coast, wrote that Opoku Ware was the wisest and most valiant man of his time in West Africa.6 When he died in 1750, a Gonja obituary notice recalled him this way:

In that year, Opoku, king of the Asante, died, may Allah curse him and place his soul in hell. It was he who injured the people of Gonja, oppressing them and robbing them of their property at will. He ruled violently, as a tyrant, delighting in his authority. People of all the horizons feared him greatly.7

Asante traditions glorify their military victories, and there can be no doubt that war was the engine that drove them to prominence. But their far-flung subject people could not have been held together, much less made to contribute to the prosperity of the empire, without skillful governance. Beginning with Opoku Ware’s successor, Osei Kwadwo, far-reaching steps were taken to permit the Asante government in the capital city of Kumase to rule effectively. Unlike the Romans, who stationed professional soldiers—the legions—in conquered territories to maintain order, Asante kings had no full-time soldiers. All their fighting men, whether free or slave, were only part-time soldiers who returned to their ordinary economic pursuits after each campaign ended. Lacking the military resources to police all of their newly conquered territories, Osei Kwadwo instituted effective practices of returning to loyal chiefs and kings of these subject territories much of the tribute they delivered to Kumase, often augmented by generous gifts from the royal treasury. The new Asante king also augmented the established system of spies who reported to him, an always important source of information, but his most valuable contribution was to begin the development of a skilled bureaucracy to oversee every aspect of government.8 During the second half of the eighteenth century, Asante leaders tried to keep the empire together with shrewd diplomacy balanced with force. Though there would be fighting, none changed the course of empire until 1807, when the Asante came into conflict with the British. The first battle was fought largely by accident, but soon after, the British began to seek the destruction of the Asante Empire, and generations of Asante men and women fought and often died to defend it.

The Warrior Tradition in Africa

In most of Africa south of the Sahara, warfare and the warrior tradition were so inextricably tied to everything of importance—honor, wealth, religion, politics, even art and sexuality—that it is no exaggeration to say that most men’s reputations, fortunes, and futures depended on their martial valor. To be sure, some small societies had no tradition of warfare and tried to avoid fighting by fleeing into dense forests, remote mountains, or barren deserts. Others only now and then engaged in warfare that led to great loss of life or property; for the most part, these societies fought only to capture women or animals or to prove their courage, not to slaughter their enemies. But a large number of African societies used their huge armies to kill, enslave, and conquer their neighbors in wars that continued seemingly without end.

Prior to the large-scale introduction of firearms from Europe, African armies shared a similar set of weapons. Except in the savannas and deserts of western and central Africa, where men rode horses and camels, African soldiers fought on foot. Frequently protected by tough cowhide shields, they threw spears or stabbed with them, used bows and sometimes poisoned arrows, and carried swords, clubs, and knives. While their weapons were similar, their tactics varied greatly. Some relied on stealth to surprise their enemies, some specialized in ambushes; others favored massive twopronged enveloping attacks, and still others built formidable fortresses. Although some societies maintained peaceful relations with their neighbors or made alliances that protected their interests, warfare was an ever-present fact of life over much of Africa.

In addition to fighting among themselves, Africans fought against foreigners who came in search of ivory, gold, hides, and slaves. Chinese, Malay, and Indian traders were usually content to carry out peaceful trade from anchorages along the coast, as were those Arabs who crossed the Sahara to trade with the great African states of West Africa. However, the great Arab caravans, containing as many as a thousand men armed with muskets who marched a thousand miles or more into the interior of East Africa in search of slaves and ivory, sometimes met with resistance.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach Africa, and at times they too relied on peaceful trade; but as early as 1575 a Portuguese priest in Angola wrote to his superiors that the Africans would have to be conquered by force because “the conversion of these barbarians will not be attained by love”.9 Angolans resisted Portuguese demands for slaves and for conversion to Christianity so fiercely that they fought them every year from the mid-1500s to 1680, when the Portuguese troops finally established their rule. Their profits were immense, especially from the slave trade. (The Portuguese eventually shipped millions of slaves to Brazil, most of them from Angola.) However, in West Africa, where the Portuguese had sought gold and slaves since their arrival in the late fifteenth century, force was not an option, since most fifteenth century West African kingdoms could mobilize armies of twenty or thirty thousand men. Given the thickly forested terrain, the endemic diseases, the heat and rain, neither the Portuguese nor the other European powers who followed them to West Africa chose to try a contest of arms with a West African power until the nineteenth century. Eighteenth-century European writers left vivid accounts of West African armies now largely armed with muskets but still sometimes using bows and arrows or crossbows. The soldiers’ ability to march long distances carrying heavy loads impressed most observers, and so did their discipline in battle. To protect themselves against such armies, several kingdoms surrounded their cities with thick walls and deep ditches filled with sharpened stakes. The city of Kano, in northern Nigeria, was surrounded by a fiftyfoot-high, forty-foot thick wall and by two rings of ditches. The enclosed area was half the size of Manhattan.10

THE ASANTE EMPIRE Early in the 19th Century

Some of the earliest fighting took place in southern Africa, where British troops fought seven wars against the Xhosa people—“Kaffirs,” as they were disparagingly called—in the nineteenth century. In one of these, even though the British eventually managed to win, the Xhosa held off the invaders for over a year, inflicting heavy casualties on some of the most famous battalions in the British army.11 A few years later in Natal, to the north, Zulu bravery earned the undying respect of the British. Later in the century British troops usually required little more than punitive expeditions—“nigger hunts” they called them—to pacify and “civilize” restive tribes. Sometimes, though, a particular tribal group like the Kikuyu fought so hard to protect their land that more extreme measures were required. One officer wrote, “There is only one way of improving the Wakikuyu [and] that is to wipe them out; I should be only too delighted to do so, but we have to depend on them for food.”12 The Kikuyu were not renowned as warriors, but these small, naked men with their spears, swords, and bows and poisoned arrows, ...