- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

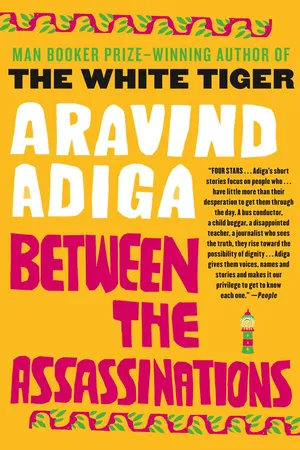

Between the Assassinations

About this book

Welcome to Kittur, India. It's on India's southwestern coast, bounded by the Arabian Sea to the west and the Kaliamma River to the south and east. It's blessed with rich soil and scenic beauty, and it's been around for centuries. Of its 193,432 residents, only 89 declare themselves to be without religion or caste. And if the characters in Between the Assassinations are any indication, Kittur is an extraordinary crossroads of the brightest minds and the poorest morals, the up-and-coming and the downtrodden, and the poets and the prophets of an India that modern literature has rarely addressed.

A twelve-year-old boy named Ziauddin, a gofer at a tea shop near the railway station, is enticed into wrongdoing because a fair-skinned stranger treats him with dignity and warmth. George D'Souza, a mosquito-repellent sprayer, elevates himself to gardener and then chauffeur to the lovely, young Mrs. Gomes, and then loses it all when he attempts to be something more. A little girl's first act of love for her father is to beg on the street for money to support his drug habit. A factory owner is forced to choose between buying into underworld economics and blinding his staff or closing up shop. A privileged schoolboy, using his own ties to the Kittur underworld, sets off an explosive in a Jesuit-school classroom in protest against casteism. A childless couple takes refuge in a rapidly diminishing forest on the outskirts of town, feeding a group of "intimates" who visit only to mock them. And the loneliest member of the Marxist-Maoist Party of India falls in love with the one young woman, in the poorest part of town, whom he cannot afford to wed.

Between the Assassinations showcases the most beloved aspects of Adiga's writing to brilliant effect: the class struggle rendered personal; the fury of the underdog and the fire of the iconoclast; and the prodigiously ambitious narrative talent that has earned Adiga acclaim around the world and comparisons to Gogol, Ellison, Kipling, and Palahniuk. In the words of The Guardian (London), "Between the Assassinations shows that Adiga...is one of the most important voices to emerge from India in recent years."

A blinding, brilliant, and brave mosaic of Indian life as it is lived in a place called Kittur, Between the Assassinations, with all the humor, sympathy, and unflinching candor of The White Tiger, enlarges our understanding of the world we live in today.

A twelve-year-old boy named Ziauddin, a gofer at a tea shop near the railway station, is enticed into wrongdoing because a fair-skinned stranger treats him with dignity and warmth. George D'Souza, a mosquito-repellent sprayer, elevates himself to gardener and then chauffeur to the lovely, young Mrs. Gomes, and then loses it all when he attempts to be something more. A little girl's first act of love for her father is to beg on the street for money to support his drug habit. A factory owner is forced to choose between buying into underworld economics and blinding his staff or closing up shop. A privileged schoolboy, using his own ties to the Kittur underworld, sets off an explosive in a Jesuit-school classroom in protest against casteism. A childless couple takes refuge in a rapidly diminishing forest on the outskirts of town, feeding a group of "intimates" who visit only to mock them. And the loneliest member of the Marxist-Maoist Party of India falls in love with the one young woman, in the poorest part of town, whom he cannot afford to wed.

Between the Assassinations showcases the most beloved aspects of Adiga's writing to brilliant effect: the class struggle rendered personal; the fury of the underdog and the fire of the iconoclast; and the prodigiously ambitious narrative talent that has earned Adiga acclaim around the world and comparisons to Gogol, Ellison, Kipling, and Palahniuk. In the words of The Guardian (London), "Between the Assassinations shows that Adiga...is one of the most important voices to emerge from India in recent years."

A blinding, brilliant, and brave mosaic of Indian life as it is lived in a place called Kittur, Between the Assassinations, with all the humor, sympathy, and unflinching candor of The White Tiger, enlarges our understanding of the world we live in today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

DAY TWO (EVENING):

MARKET AND MAIDAN

The Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Maidan (formerly King George V Memorial Maidan) is an open ground in the center of Kittur. In the evenings, it fills up with people playing cricket, flying kites, and teaching their children to ride bicycles. At the edges of the maidan, ice cream and ice candy sellers peddle their wares. All major political rallies in Kittur are held in the maidan. The Hyder Ali Road leads from the maidan to Central Market, Kittur’s largest market for fresh produce. The Town Hall of Kittur, the new law court, the Havelock Henry District Hospital, and both the premier hotels in Kittur—the Hotel Premier Intercontinental and the Taj Mahal International—are within walking distance of the market. In 1988, the first temple meant exclusively for the use of Kittur’s Hoyka community opened for worship in the vicinity of the maidan.

WITH HAIR LIKE that, and eyes like those, he could easily have passed himself off as a holy man, and earned a living sitting cross-legged on a saffron cloth near the temple. That was what the shopkeepers at the market said. Yet all this crazy fellow did, morning and evening, was crouch on the central railing of the Hyder Ali Road and stare at the passing buses and cars. In the sunset, his hair—a gorgon’s head of brown curls—shone like bronze, and his irises glowed. While the evening lasted, he was like a Sufi poet, full of mystic fire. Some of the shopkeepers could tell stories about him: one evening they had seen him on the back of a black bull, riding it down the main road, swinging his hands and shouting, as if the Lord Shiva himself were riding into town on his bull, Nandi.

Sometimes he behaved like a rational man, crossing the road carefully, or sitting patiently outside the Kittamma Devi Temple with the other homeless, as they waited for the leftovers of meals from weddings or thread ceremonies to be scraped into their clustered hands. At other times he would be seen picking through piles of dog shit.

No one knew his name, religion, or caste, so no one made any attempt to talk to him. Only one man, a cripple with a wooden leg who came to the temple in the evenings once or twice a month, would stop to give him food.

“Why do you pretend not to know this fellow?” the cripple would shout, pointing one of his crutches at the fellow with the brown curls. “You’ve seen him so many times before! He used to be the king of the number five bus!”

For a moment the attention of the market would turn to the wild man; but he would only squat and stare at a wall, his back to them and the city.

Two years ago, he had come to Kittur with a name, a caste, and a brother.

“I am Keshava, son of Lakshminarayana, the barber of Gurupura Village,” he had said at least six times on his way to Kittur, to bus conductors, toll gatherers, and strangers who asked. This formula, a bag of bedding tucked beneath his arm, and the light pressure of his brother’s fingers at his elbow whenever they were in a crowd were all he had brought with him.

His brother had ten rupees, a bag of bedding that he too tucked under his right arm, and the address of a relative written on a paper chit that he kept crushed in his left hand.

The two brothers had arrived in Kittur on the five p.m. bus. They got off at the bus station; it was their first visit to a town. Right in the middle of the Hyder Ali Road, in the center of the biggest road in all of Kittur, the conductor had told them that their six rupees and twenty paise would take them no farther. Buses charged around them, with men in khaki uniforms hanging from their doors, whistles in their mouths that they blew on screechingly, shouting at the passengers, “Stop gaping at the girls, you sons of bitches! We’re running late!”

Keshava held on to the hem of his brother’s shirt. Two cycles swerved around him, nearly running over his feet; in every direction, cycles, autorickshaws, and cars threatened to crush his toes. It was as if he were at the beach, with the road shifting beneath him like sand beneath the waves.

After a while, they summoned up the courage to approach a bystander, a man whose lips were discolored by vitiligo.

“Where is Central Market, uncle?”

“Oh, that…It’s down by the Bunder.”

“How far is the Bunder from here?”

The stranger directed them to an autorickshaw driver, who was massaging his gums with a finger.

“We need to go to the market,” Vittal said.

The driver stared at them, his finger still in his mouth, revealing his long gums. He examined the moist tip of his finger. “Lakshmi Market or Central Market?”

“Central Market.”

“How many of you?”

And then: “How many bags?”

And then: “Where are you from?”

Keshava assumed that these questions were standard in a big city like Kittur, that an autorickshaw driver was entitled to such inquiries.

“Is it a long distance away?” Vittal asked desperately.

The auto driver spat right at their feet. “Of course. This isn’t a village, it’s a city. Everything’s a long distance from everything else.”

He took a deep breath and sketched a series of loops with his damp finger in the air, showing them the circuitous path that they would have to take. Then he sighed, giving the impression that the market was incalculably far away. Keshava’s heart sank; they had been swindled by the bus driver. He had promised to drop them off within walking distance of Central Market.

“How much, uncle, to take us there?”

The driver looked at them from head to toe, and then from toe to head, as if gauging their height, weight, and moral worth: “Eight rupees.”

“Uncle, it’s too much! Take four!”

The autorickshaw driver said, “Seven twenty-five,” and motioned for them to get in. But then he kept them waiting in the rickshaw, their bundles on their laps, without any explanation. Two other passengers negotiated a destination and a fare and crammed in; one of them sat on Keshava’s lap without any warning. Still the rickshaw did not move. Only after another passenger joined them, sitting in the front beside the driver, and with six people crammed into the tiny vehicle that had space for three, did the driver start kicking on his engine’s pedal.

Keshava could barely see where they were going, and thus his first impressions of Kittur were of the man who was sitting on his lap: of the scent of the castor oil that had been used to grease his hair and the hint of shit that he produced when he squirmed. After dropping off the rider in the front seat, and then the two men at the back, the autorickshaw meandered for some time through a quiet, dark area of town, before turning into another cacophonous street, lit by the glaring white light of powerful paraffin lamps.

“Is this Central Market?” Vittal shouted at the driver, who pointed to a sign:

KITTUR MUNICIPALITY CENTRAL MARKET:

ALL MANNER OF VEGETABLES AND FRUIT

AT FAIR PRICES AND EXCELLENT FRESHNESS

“Thank you, brother,” Vittal said, overwhelmed with gratitude, and Keshava thanked him too.

When they got out, they found themselves once again in a vortex of light and noise; they kept very still, waiting for their eyes to make sense of the chaos.

“Brother,” Keshava said, excited at having found a landmark that he recognized. He pointed: “Brother, isn’t this where we started out?”

And when they looked around, they realized that they were only a few feet away from where the bus driver had set them down. Somehow they had missed the sign, which had been right behind them all the time.

“We were cheated!” Keshava said in an excited voice. “That autorickshaw driver cheated us, Brother! He—”

“Shut up!” Vittal whacked his younger brother on the back of his head. “It’s all your fault! You’re the one who wanted to take an autorickshaw!”

The two of them had been brothers for only a few days.

Keshava was dark and chubby; Vittal was tall and lean and fair, and five years older. Their mother had died years ago, and their father had abandoned them; an uncle had raised them, and they had grown up among their cousins (whom they also called “brothers”). Then their uncle had died, and their aunt called Keshava and told him to go with Vittal, who was being dispatched to the big city to work for a relative who ran a grocery shop. And that was, really, how they had come to realize that there was a bond between them deeper than that between cousins.

They knew that their relative was somewhere in the Central Market of Kittur: that was all. Taking timid steps, they went into a dark market area where vegetables were being sold, and then, through a back door, they went into a well-lit market where fruits were being sold. Here they asked for directions. Then they walked up steps that were covered in rotting garbage and moist straw to the second floor. Here they asked again:

“Where is Janardhana the store owner from Salt Market Village? He’s our kinsman.”

“Which Janardhana—Shetty, Rai, or Padiwal?”

“I don’t know, uncle.”

“Is your kinsman a Bunt?”

“No.”

“Not a Bunt? A Jain, then?”

“No.”

“Then of what caste?”

“He’s a Hoyka.”

A laugh.

“There are no Hoykas in this market. Only Muslims and Bunts.”

But the two boys looked so lost that the man took pity, and asked someone, and found out that there were indeed some Hoykas who had set up shop near the market.

They walked down the steps, and went out of the market. Janardhana’s shop, they were told, displayed a large poster of a muscular man in a white singlet. They couldn’t miss it. They walked from shop to shop and then Keshava cried, “There!”

Beneath the image of the man with the big muscles sat a lean shopkeeper, unshaven, who was reading a notebook with his glasses down on the bridge of his nose.

“We are looking for Janardhana, from Gurupura Village,” Vittal said.

“Why do you want to know where he is?”

The man was looking at them suspiciously.

Vittal burst out, “Uncle, we’re from your village. We’re your kin.”

The shopkeeper stared. Moistening the tip of a finger, he turned another page in his book.

“Why do you think you’re my kin?”

“We were told this, Uncle. By our auntie. One-Eyed Kamala.”

The shopkeeper put the book down.

“One-Eyed Kamala’s…ah, I see. And what happened to your parents?”

“Our mother passed away many years ago, after Keshava’s—this fellow’s—birth. And four years ago, our father lost interest in us and just wandered away.”

“Wandered away?”

“Yes, Uncle,” Vittal said. “Some say he’s gone to Varanasi, to do yoga by the banks of the Ganges. Others say he’s in the holy city of Rishikesh. We haven’t seen him in many years; we were raised by our uncle Thimma.”

“And he…?”

“Died last year. We stayed on, and then it was too much for our aunt to support us. The drought was very bad this year.”

The shopkeeper was amazed that they had come all this way, without any prior word, on so thin a connection, just expecting that he would take care of them. He reached down into a counter, bringing out a bottle of arrack, which he uncapped and put to his lips. Then he capped the bottle and hid it again.

“Every day people come from the villages looking for work. Everyone thinks that we in the towns can support them for nothing. As if we have no stomachs of our own to feed.”

The shopkeeper took another swig of his bottle; his mood improved. He had rather liked their naïve recounting of that story of daddy having gone to “the holy city of Rishikesh…to do yoga.” Old rascal is probably shacked up with a mistress somewhere, and taking care of a brood of bastards, he thought, smiling in approval at how you can get away with anything in the villages. Stretching his hands high above his head as he yawned, he brought them down onto his stomach with a loud whack.

“Oh, so you’re orphans now! You poor fellows. One must always stick to one’s family—what else is there in life?” He rubbed his stomach. Look at the way they are staring at me, as if I were a king, he thought, feeling suddenly important. It was not a feeling he had had often since coming to Kittur.

He scratched his legs. “So, how are things in the village these days?”

“Except for the drought, everything’s the same, Uncle.”

“You got here by bus?” the shopkeeper asked. And then, “From the bus stand, you walked over here, I take it?” He got up from his seat. “Autorickshaw? How much did you pay? Those fellows are total crooks. Seven rupees!” The shopkeeper turned red. “You imbeciles! Cretins!”

Apparently holding the fact that they had been cheated against them, the shopkeeper ignored them for half an hour.

Vittal stood in a corner, his eyes to the ground, crushed by humiliation. Keshava looked around. Red-and-white stacks of Colgate-Palmolive toothpaste and jars of Horlicks were piled behind the shopkeeper’s head; shiny packets of malt powder hung from the ceiling like wedding bunting; blue bottles of kerosene and red bottles of cooking oil were stacked in pyramids up at the front of the shop.

Keshava was dark-skinned, with enormous eyes that stared lingeringly. Some of those who knew him insisted he had the energy of a hummingbird, and was always flapping around, making a nuisance of himself...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- Also by Aravind Adiga

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Arriving in Kittur

- Day One The Railway Station

- Day One (Afternoon) The Bunder

- Day Two Lighthouse Hill

- Day Two (Afternoon) St. Alfonso’s Boys’ High School and Junior College

- Day Two (Evening) Lighthouse Hill (The Foot of the Hill)

- Day Two (Evening) Market and Maidan

- Day Three Angel Talkies

- Day Four Umbrella Street

- Day Four (Afternoon) The Cool Water Well Junction

- Day Five Valencia (To the First Crossroads)

- Day Five (Evening) The Cathedral of Our Lady of Valencia

- Day Six The Sultan’s Battery

- Day Six (Evening) Bajpe

- Day Seven Salt Market Village

- Chronology

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.