- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

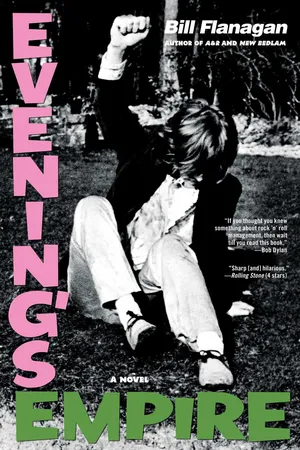

About this book

THE YEAR IS 1967.

In England, and around the world, rock music is exploding—the Beatles have gone psychedelic, the Stones are singing "Ruby Tuesday," and the summer of love is approaching. For Jack Flynn, a newly minted young solicitor at a conservative firm, the rock world is of little interest—until he is asked to handle the legal affairs of Emerson Cutler, the seductive front man for an up-and-coming group of British boys with a sound that could take them all the way.

Thus begins Jack Flynn’s career with the Ravons, a forty-year journey through London in the sixties, Los Angeles in the seventies, New York in the eighties, into Eastern Europe, Africa, and across America, as Flynn tries to manage his clients through the highs of stardom, the has-been doldrums, sellouts, reunions, drug busts, bad marriages, good affairs, and all the temptations, triumphs, and vanities that complicate the businesses of music and friendship.

Spanning the decades and their shifting ideologies, from the wild abandon of the sixties to the cold realities of the twenty-first century, Evening’s Empire is filled with surprising, sharply funny, and perceptive riffs on fame, culture, and world events. A firsthand observer and remarkable storyteller, author Bill Flanagan has created an epic of rock-and-roll history that is also the life story of a generation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

With the money I made from selling my house in Los Angeles I was able to buy an airy three-bedroom apartment with French doors opening onto a brick balcony on the east end of Gramercy Park. I rented an office nearby, on Union Square, and hired two assistants who were young, bright, and had no interest in rock and roll. I had learned how much that helped.

In April 1980 I went to London for label meetings and to visit my mother. Each time I saw her I was initially shocked at how old she looked, and then relieved by how young she acted.

She and my aunt were still in the house in Kingston. I had tried many times to convince her to let me buy her a bigger home but she would not hear of it. On this trip, I learned that the little cottage next to my mother’s was for sale. It was a five-room wooden house with an old stone fireplace and a large garden that abutted my mother’s backyard. On a whim, I bought it. If I could not convince Mam to move into someplace bigger, I could at least expand the property around her. I invited my cousin Mary, my aunt’s daughter, to live in the new house and keep it occupied.

Mam’s reaction was, “Oh, how lovely, Jack. Now you’ll have a place to live when you settle down.” I thought that was funny at first, but later wondered if she did not know me better than I knew myself. There probably was a part of me that thought all this living-in-America stuff was temporary and I would eventually want to have the option of moving home. To marry a nice English girl, have children, and grandma next door? It didn’t seem like the worst idea I’d ever heard.

For the worst idea I’d ever heard I could count on my old comrade Simon Potts. He had learned I was in London and phoned me incessantly to meet with him.

I called on Simon at a Bayswater hotel where he was living. After a decade of spending three hundred days a year on the road, Simon had become institutionalized. Living in a house or flat unnerved him. He hated having to clean up after himself or hire someone else to. He hated being responsible for his own security, laundry, or decorating. When his telephone rang he wanted someone else to answer and give him the message.

Tug Bitler had worked out a deal with a second-rate hotel north of Hyde Park to lease Simon a small suite on a month-to-month basis. This was all done through Tug’s management and touring company, so Simon never saw a bill. When he explained the arrangement to me I warned him that somewhere in the bowels of Tug’s business a meter was running. Every time Simon called down to room service for an omelet, a charge was ticking over.

Simon said that was why he wanted to see me.

“I need you to look into things with Tug,” he said. “I’ve got a feeling he’s taking more than his share.”

Christ, I thought, this is where I came in. I had not seen Tug in years, although we corresponded about Ravons catalog business and the fifty or sixty compositions on which our clients shared publishing. I knew that he had artists other than Simon, all of whom were of roughly the same professional disposition: heavy rock bands, metal acts, and Thunderjug, a Swedish progressive rock unit who rarely got played on the radio, sold moderate numbers of albums, but made money on the road pounding out loud and repetitive riffs for frustrated young men of many nationalities. Among this legion of vulgarians, Simon was the most senior and, by the standards of the genre, the most intellectual.

“As your friend, Simon,” I said, “I am happy to look through your contracts informally and advise you about any monkey business. But let’s try to find a way to do this without alerting Tug, all right? He’ll set fire to the paperwork and then set fire to me.”

Simon nodded. “I have copies of everything,” he said.

“Good. Here?”

“No, in the office.”

“You mean in Tug’s office?”

“Well, he is my manager.”

“Of course. See if you can borrow them when he’s out on the road with one of his other bands, will you? I’m too old to be hung out any windows.”

Simon told me something that surprised me: “Tug doesn’t go out on the road. Ever. He hasn’t in years. He barely comes out of his house. You should see it. Big pile out by Heathrow. He has guard dogs, an electric fence, the whole thing. When he does come into town he rides in an armored limousine he bought from the Soviet embassy. Gets about nine kilometers to a tank of petrol. He’s not the Tug you knew and loved.”

This does not sound promising at all, I thought. If I had any sense I would have told Simon to find another auditor. But I did not have it in me to turn him away. Although I came very close when he added to my burdens by announcing, “I want to play you my new album.”

Spare me, I thought. “Love to hear it,” I said.

We took the lift to Simon’s rooms, where he cued up his latest concept record, which was titled Synthenesia. It was long, lugubrious, and painfully self-referential. There is nothing wrong with writing a suite of songs in the first person, if there is a reasonable opportunity for the listener to see himself in the “I.”

“I Can’t Turn You Loose.”

“I Wish It Would Rain.”

“I Want You.”

“I’ll Be There.”

“I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

Nothing wrong with any of those. Simon, however, had pretty much eliminated any possibility of the “I” in his opera being mistaken for anyone other than Simon Potts. Beneath the usual Dungeons & Dragons metaphors, Synthenesia was the story of a legendary rock star who goes to war single-handed against an army of incompetents, sycophants, and corporate villains who want to keep the great man (who shares Simon’s birth date, birthplace, disposition, and given name) from reaching the audience who are hungry for his heroic message.

We listened for almost an hour and then Simon said, “Now here’s the second half.” At that point I began drinking.

When it finally ended I had entered the tranquillity of the whiskey brain bath, which perhaps made me a bit more honest than I otherwise would have been. Or perhaps not–I had been kissing Emerson’s ass all week. Simon was not my client and he had pretty much put a pistol to my head and demanded my opinion.

“Some of it’s quite good,” I said, tiptoeing to the lip of the dragon’s cave. “I like the instrumental very much, it has a sort of majesty.”

Simon waited for what was coming.

“I’m not certain you’re doing yourself any favors making it a double album,” I ventured. “Seems to me that if you took the ten best tracks you’d have a very strong single LP.”

Simon sneered. “Then we’d lose the story, wouldn’t we?”

“Screw the story, Simon,” I said, refilling my glass. “No one will understand it but you anyway.”

“Which is the whole point, Flynn. It details exactly what I have gone through in this corrupt business. It is my journey. To begin editing it to make it more palatable to the simpleminded would be to make it a lie. I am a truth-teller. That is my job.”

I was so sick of hearing this kind of tripe for so long that I am afraid I took it out on Simon a little. I said, “Fancy that, I thought your job was making music. I thought people paid you to entertain them.”

Simon took umbrage. “I am not an entertainer. I am an artist!”

“Forgive me,” I said, “I am a Philistine, but don’t artists get to be artists by expressing something the public can relate to or aspire to or at least find compelling?”

“You don’t find Synthenesia compelling?”

“I find some of it compelling, Simon. I find some of it a bit annoying, to be honest. All I’m suggesting is that you might profit by taking out some of the annoying bits. Like when you say, ‘He traded it all for a corner office and a color TV.’ You know, all TVs are color TVs now. They haven’t made black and white TVs in a long time. And the bit about you knowing pain and the rest knowing only self-pity. Forgive me, but it’s the most self-pitying thing I’ve ever heard. You’re painting a big fat target on your head with that one.”

“Maybe it’s not for you, Flynn,” Simon said. “Maybe you are not my audience.”

“No argument there, mate. But perhaps your”–here I almost said “dwindling” but I stopped myself–“audience doesn’t need to see every side of you. Show ’em your best face, by all means. Show them your wit and your smarts and your diligence. Show them your righteous anger, Simon, that’s fine, that’s your gift. Just don’t show them your arsehole, that’s all I’m saying.”

Simon looked down his long nose at me and passed sentence. “My arsehole is part of who I am, Flynn. That is the difference between entertainment and art. Art does not deny the arsehole.”

I thought, You said it, pal, but what I said was, “Well, then, art better be a comfort when your audience is gone.”

We parted on bad terms that night. I had hoped to be an honest friend by telling Simon what he needed to hear before the label and critics sent him the same message in a cascade of poison arrows. It was hopeless. Simon had signed onto the new solipsism. Creative integrity meant singing your diary and if your diary that day consisted of a bad case of the trots, that became your next libretto.

When I returned to New York, Emerson was in a foul mood. He had finally released his new and overbudget album, Rock & Roll Criminal, to the worst reviews of his career.

He was in my office on Union Square pacing up and down and reading aloud from a pile of clippings that our publicist Wendy had been stupid enough to collate and present to him. She should have put them in her mouth and swallowed.

“‘Pathetic attempt to be modern by laid-back dinosaur.’”

“‘Emerson Cutler has stayed on the train way past his stop.’”

“‘That this sort of tired shit is on a major label while the most vital new bands in rock and roll toil in obscurity shows why the old record corporations are destined for the junk heap of history.’”

Wendy said, “That’s really more about the label than you, Em.”

“I spent half a million dollars on that album!” Emerson erupted. “What the hell do these little twits want from me?”

Wendy said, “I think you’ve got to lose the beard.”

“Here’s what I’d like to know,” Emerson declared. “Have any of these jack-offs ever made a record? Entertained an audience? Written a song? I’d like to hear it! What qualifies them to piss on my work?”

“They’re supposed to represent the audience, not the musician,” Wendy explained.

Emerson looked at her, astonished. “Oh really! Oh, are they? Oh, do they? They represent all those people filling my sold-out shows and buying my albums? Is that who they represent? Eh, Wendy? Because when I look through these rags”–here he grabbed a copy of Trouser Press magazine from the top of the pile–“I see that these self-anointed representatives of the audience are very enthusiastic about”–he began reading off names from the table of contents–“Fripp and Eno. The Modern Lovers. The Damned. Gang of Four. Oingo fucking Boingo. Yeah, there’s the vox populi, all right. There’s the taste of the average fan reflected!”

Emerson fell into a chair and began flipping through the magazine. He stopped at a feature story extolling a punk band called the Tin Pagans. He held it up. “Get a load of this,” he said.

I looked at the black and white photo and said, “So what?”

He pointed to the byline on the article. “By Fred Zaras.” He began reading. “Lead singer Bob Hymen explains the almost feral response he solicits from the crowd by opining, ‘We are tuned in to something shifting in the mass unconsciousness. The tectonic plates are moving under the collective psyche and we have tapped into that evolution.’”

Emerson looked from Wendy to me to Wendy. We all burst out laughing at once.

“Fred has found another mouthpiece for his theories,” I said.

“Creep,” Wendy snapped.

“We should have kept him in our camp, Flynn,” Emerson told me, his mood lightening a little. “He’s the reason the press turned against me.”

“Come on, Em,” I said. “He was a tosser, and besides that, he was insane. You think Cynthia would have put up with him hanging around anymore?”

Emerson threw down the magazine.

Except for some daily newspaper reviewers who were older than we were, most of the rock press had turned against Emerson after punk rock seized their imaginations. Say what you will about punk, it was easy to write about. It’s a lot simpler to come up with copy about a singer who runs a razor blade down his chest than it is to talk about the unexpected introduction of a minor augmented chord into a major progression.

Emerson was no longer being evaluated based on whether he made a good Emerson Cutler record or a bad Emerson Cutler record. Now the record was prima facie bad because it was Emerson Cutler, who played blues-based music with lyrics about love, lost and found, containing conventional guitar solos and studio musicians. Plus, he had been around since the sixties and was nearly forty years old.

All of these predispositions and antecedents condemned his record before it ever reached the stereo. On the other hand, the Tin Pagans, the new favorites of Zaras, played short songs with simple chords, a straight beat (no swing), very occasional solos (and those incompetently executed), and descended from the Stooges, the MC5, and the Ramones. They had the right pedigree. Anything the Tin Pagans did was lauded and their record need not be played to ascertain its quality, either. These new rock writers were not reviewing music, they were reviewing ideology.

“I’ll tell you one thing,” Emerson announced before he went home. “I would never criticize anyone for doing something I had never done myself. That’s my point. If they’ve got some songs to share, let’s hear ’em. Otherwise, shut up and sit down. If I had never done something myself, I would keep my uninformed opinions to myself.”

We nodded assent. Still, I considered how many things I had heard Emerson offer opinions about that he had never done himself, sometimes from the stage or in interviews. Emerson had vivid opinions about politics, though he had never run for office or in any way gotten involved in any social action. He could hold forth at great length over dinner about the shortcomings of various actors, directors, authors, TV presenters, painters, designers, and, God knows, journalists, though he had never practiced any of those trades. We were all critics. The difference was that we did not all get paid for it.

When Emerson had gone, I asked Wendy if we had any other business, or whether she had come over only to make my client miserable. Wendy had left Tropic Records and started her o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Preface

- THE ONLY WAY TO BE

- ROUGH MIX

- THE SOUND OF THE SINNERS

- THE DRUGS DON’T WORK

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evening's Empire by Bill Flanagan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.