This is a test

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

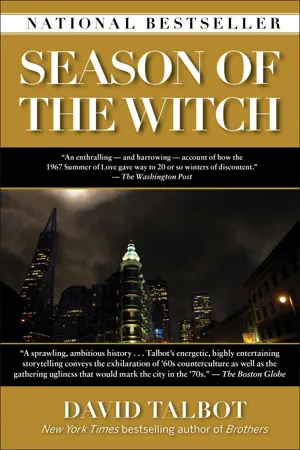

The critically acclaimed, San Francisco Chronicle bestseller—a gripping story of the strife and tragedy that led to San Francisco's ultimate rebirth and triumph. Salon founder David Talbot chronicles the cultural history of San Francisco and from the late 1960s to the early 1980s when figures such as Harvey Milk, Janis Joplin, Jim Jones, and Bill Walsh helped usher from backwater city to thriving metropolis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Season of the Witch by David Talbot in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

ENCHANTMENT

Listen, my friends . . .

1

SATURDAY AFTERNOON

MICHAEL STEPANIAN LOOKED up from the blood and muck of his rugby game at a dazzling vision in the sky. A parachutist came drifting slowly through the wisps of fog over Golden Gate Park, his billowing, paisley chute aglow in the afternoon’s soft winter light. The skydiver landed in the midst of a sprawling festival that was being held at the opposite end of the Polo Field, and the crowd instantly swallowed him.

Stepanian was a tough young Armenian-American from New York who had recently graduated from Stanford Law School and was now working in Vincent Hallinan’s legendary law office. On weekends, Stepanian played rugby for the Olympic Club, the same athletic organization where old man Hallinan played rugby and football and boxed, long after men his age were supposed to quit. All through the afternoon, as the Olympic Club rolled to lopsided 23–3 victory over visiting Oregon State University, the burly rugby players snarled at the long-locked festivalgoers whenever they trespassed on their side of the field. But Stepanian, intrigued by the waves of music and good cheer, strolled over to the festival after the game and wandered around in his battle-torn jersey and muddy cleats. “I looked like I was from a different planet, but nobody seemed to give a shit. The sun was shining, the kids were beautiful, the music was magic. That was the beginning of my education.”

It was the Human Be-In, the January 14, 1967, celebration that was billed as a coming together of every tribe in the new, emerging America: from legendary beats, to Berkeley radicals, to the San Francisco love generation. “For ten years a new nation has grown inside the robot flesh of the old,” proclaimed the event’s starry-eyed press release. “The night of bruted fear of the American eagle-beast-body is over. Hang your fear at the door and join the future. If you do not believe, please wipe your eyes and see.”

Years later, some would call this event the true—if belated—beginning of the sixties. More than twenty thousand people poured into the Polo Field that sun-dappled Saturday, on the wild west side of Golden Gate Park, where a swaying curtain of eucalyptus and Monterey pine trees shielded the tribal gathering from the raw ocean winds. Onstage, Allen Ginsberg—wearing white Indian pyjamas and garlands of beads and flowers—looked out over the vast human dynamo that he had helped ignite and turned to his friend, Lawrence Ferlinghetti: “What if we’re wrong?”

It was a typical Ginsberg remark, and its whimsy and self-doubt reflected the better angels of the growing counterculture movement. The radical Berkeley component among the Be-In organizers, led by antiwar leader Jerry Rubin, was more certain about things. They sought to enlist the crowd in their political mission. But San Francisco’s more ethereal ethos prevailed that day.

The leading icons of the emerging counterculture were all gathered onstage: Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, and fellow poet-shaman Gary Snyder; psychedelic carnival barker Timothy Leary; the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company. But the more enlightened among them knew that the crowd itself was the center stage—no one was really listening to the speakers and singers.

The Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner—San Francisco homeboy, and a shrewd product of Bay Area Catholic schools—got it. “The difference between San Francisco and Berkeley was that Berkeley complained about a lot of things. Rather than complaining about things, we San Franciscans formed an alternative reality to live in. And for some reason, we got away with it. San Francisco became somewhere you did things rather than protesting about them. We knew we didn’t have to speechify about what we should and shouldn’t do. We just did.”

The Airplane’s “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love” would soon become part of the cultural revolution’s soundtrack and make the band world-famous. But Kantner knew at heart they would always be a Haight-Ashbury house band, just like the Dead. He later memorialized the Be-In festival in song: “Saturday afternoon / Yellow clouds rising in the noon / Acid, incense, and balloons.”

Young people sprawled on the grass, playing pennywhistles, harmonicas, guitars, and flutes. Naked toddlers chased their shadows in the sun. Only two mounted policemen patrolled the grounds; one came trotting through the crowd on his horse, cradling a small child in his arms. The loudspeaker announced, “A lost child has been delivered to the stage and is now being cared for by the Hell’s Angels.” It was a time when that made sense.

As the sun slipped into the Pacific, Ginsberg blew on a conch shell and beckoned everyone to turn to the west and watch the final sparks of daylight. Then he asked everyone to clean up the trash, so that they would leave the Polo Field—which he and Snyder had blessed at the beginning of the festival—just as they found it. Ginsberg, a cross between holy man and Jewish mother, was precisely the beneficent figure that the infant movement needed.

Rev. Edward “Larry” Beggs, a thirty-four-year-old Congregational youth minister who had come to the Be-In out of curiosity with his wife, Nina, was surprised to see the people all around him do as Ginsberg suggested. “Because I had seen how my fellow Americans could trash out even a sacred space like Yosemite National Park,” he recalled, “I was amazed to see the people around me picking up not only their own discarded items but other people’s paper cups, bottle caps, orange peels, and cigarette butts. The entire Polo Field, where thousands had sat and munched longer than a baseball double-header, was now restored to its pristine green.”

The tousle-haired, bespectacled Beggs—who looked like one of John Kennedy’s young Peace Corps volunteers—felt like Bob Dylan’s Mr. Jones: he knew something was happening here, but didn’t know what it was. Within a few months, the quiet lives of Ed and Nina Beggs would be turned upside down. Ed would be jailed for running a teenage shelter, the nation’s first haven for the growing swarm of boys and girls who were fleeing homes seemingly everywhere in America. And Nina would find herself on the witness stand, testifying for the defense in the obscenity trial of Lenore Kandel, an erotic poet who roared around town on the back of a motorcycle driven by her lover, a ruggedly beautiful Hell’s Angel known as Sweet William.

Kandel—a curvy, sloe-eyed, olive-skinned goddess who wore her hair in Pocahontas braids—set off a tempest when she published The Love Book. Her poetry collection was an orgasmic celebration of carnal love, filled with rising cocks, honeycomb cunts, and “thick sweet juices running wild.” Kandel made a strong impression onstage at the Human Be-In, reading her passion poems from a clipboard and then tearing off each one as she finished, crumpling it in her fist, and tossing it into the crowd. But it wasn’t until a few months later, when copies of The Love Book were confiscated at a Haight Street bookstore by San Francisco police, that she became another infamous counterculture name. Kandel’s obscenity trial would become one of Catholic San Francisco’s last stands against the onrushing cultural revolution.

On the witness stand, Nina Beggs made a strong impression for the defense. She was no dark-banged folksinger type; she was a pretty, blond, pageboy-coiffed clergyman’s wife. But she too found salvation in Kandel’s ecstatic poetry. Nina testified that she had devoured The Love Book in one gulp at the Psychedelic Shop, after dining with her husband at a nearby Haight-Ashbury restaurant. After finishing the poetry in the bookstore, she turned to her husband and urged him to read it. “This is the way it is for a woman,” she told Ed. “This is what making love does for me.” Then, speaking in a slow, clear voice, Nina shared her joy with the packed courtroom. “The oceanic” sexual feeling expressed in The Love Book, she said, is “one of the greatest proofs you have of your connection with God.”

THE HUMAN BE-IN was the beginning of the story for thousands of people, many of whom would go on to take primary roles in San Francisco’s revolution. In the crowd that day were Margo St. James, a big-hearted cocktail waitress and occasional hooker who would later found the prostitute rights movement; Stewart Brand, an army veteran and aspiring artist who jumped on Ken Kesey’s bus and later launched the Whole Earth Catalog and linked the counterculture to the digital future; Peter Coyote, cofounder of the Diggers, the “heavy hippie” anarchists who turned San Francisco into one big stage for their radical theater.

And there was Michael Stepanian, in his rugby battle gear. It was Stepanian who would defend dozens of Be-In celebrants when they were rounded up by police later that evening on Haight Street. He would go on to represent the Grateful Dead when their Haight-Ashbury house was raided by the drug squad, and cartoonist Robert Crumb when he was charged with obscenity. Like The Love Book trial, these legal battles would help widen the circle of light in San Francisco.

“When we started out, the city was antiblack, antigay, antiwoman. It was a very uptight Irish Catholic city,” said Brian Rohan, Stepanian’s legal sidekick and another brawling protégé of Vincent Hallinan. “We took on the cops, city hall, the Catholic Church. Vince Hallinan taught us never to be afraid of bullies.”

By taking on the bullies, the new forces of freedom began to liberate San Francisco, neighborhood by neighborhood. They began with the Haight-Ashbury.

2

DEAD MEN DANCING

IN THE MID-1960S, San Francisco was still a city of tribal villages. The Castro district and the Noe Valley neighborhood were working-class Irish, though the Irish in the adjacent Mission district were giving way to Latino immigrants. The Fillmore section still clung to its reputation as the Harlem of the West, though the redevelopers’ wrecking ball was reducing its former glory block by block. The Italians in North Beach lived in uneasy proximity to Chinatown. At one time, the Chinese could cross over Broadway—the boulevard that divided the two communities—only at their own peril.

The cultural revolution first came to North Beach, where cheap saloons and fleabag hotels and old Barbary Coast bohemianism beckoned the beats in the 1950s. Ferlinghetti was among the first. He was a World War II navy veteran and an aspiring poet and painter when he disembarked at the ferry building in 1951, wandering into North Beach with his sea bag slung over his shoulder. “It was a small city, nestled into the hills,” he recalled. “All the buildings were white, there were no skyscrapers. It felt Mediterranean. It was beautiful.”

A couple of years later, Ferlinghetti opened up City Lights Books with partner Peter Martin, son of the assassinated anarchist Carlo Tresca. Italian garbage truck drivers would roar up to the curb and run inside to buy the anarchist newspapers that the store got directly from Italy. It was a cramped one-room establishment in those days; they didn’t even own the basement, which is where the Chinese New Year Parade’s endless, red and gold dragon was tucked away the other 364 days of the year. But City Lights became a beacon to the poets, wanderers, and angel-headed hipsters who were making their way to San Francisco. You could browse forever, and nobody would bother you. It was here that Ferlinghetti first met Ginsberg, who entered the store one day trailed by his usual crowd of young men, looking more like a horn-rimmed Columbia University intellectual than the wild Whitman of Cold War America. Ginsberg would pound out “Howl” on his typewriter a few blocks away in his railroad apartment at 1010 Montgomery Street.

North Beach’s Little Italy coexisted happily with the beat underground and the new folk and jazz clubs, topless bars, and gay caverns that began popping up in the neighborhood. But it was not North Beach where counterculture history would be made in the 1960s. It was across town in the Haight-Ashbury, a neighborhood of once ornate Victorian “painted ladies” that had seen better days. By the early sixties, the old Irish and Russian neighborhood had become so dilapidated that, like the Fillmore district, it was slated for demolition, to make room for a freeway extension along the Panhandle—the strip of greenery that led to Golden Gate Park. But the Haight was now populated by a feisty mix that included black home owners who had already been pushed out of one neighborhood, the Fillmore; artists and bohemians squeezed out of North Beach by tourists and rising rents; gays, who appreciated the neighborhood’s live-and-let-live atmosphere; and San Francisco State College students, who desperately needed the cheap living quarters they found in the neighborhood’s subdivided Victorian flats. San Francisco State was the launch pad for many of the young civil rights activists who headed to the Deep South each summer—including Terry Hallinan—and they came back to San Francisco a battle-hardened corps. The Haight’s residents knew how to fight city hall. This time the redevelopment agency’s bulldozers were stopped.

THE HAIGHT WAS NOW safe to become a haven for the young, broke, and visionary. Among them was a beautiful, dark-haired elementary schoolteacher named Marilyn Harris, who moved into a Victorian flat on Ashbury Street in the summer of 1965. Two years earlier, Harris had walked out on her marriage to an Arizona lawyer and hopped on a Greyhound bus to San Francisco. She knew she belonged there ever since she and her husband had visited the city in 1960, taking in slashing comedy acts like Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, and Dick Gregory at the hungry i and other North Beach clubs and reveling in the city’s breezy sense of freedom.

“Oh my God, this is where I’m supposed to live,” Marilyn excitedly told her husband. Would he start over with her in San Francisco?

“Ah, no,” he replied.

She arrived alone at the Greyhound station in downtown San Francisco, with $10 in her purse. She walked to a nearby motel and phoned her parents in New Jersey, asking them for enough money to start her new life, but they refused. So she walked into a Bank of America office. Based on her word that she was lining up a job as an elementary schoolteacher, the bank extended her a $400 loan. This is when the bank was still a local institution, and its corporate culture still held traces of its founder, Amadeo Pietro Giannini, who began the bank in a North Beach saloon and became known for extending loans to working people and not just high rollers.

The Haight was still just a scruffy, fog-bound neighborhood when Marilyn moved there, with Russian bakeries where you could buy piroshkis. But the fairy dust was already floating overhead. The year after she settled in the Haight, a young band called the Grateful Dead moved into a big Victorian across the street at 710 Ashbury. Janis Joplin rambled around the neighborhood in her scarves and boas, swigging from a bottle of Ripple with her bandmates, and Marilyn would bump into her at Peggy Caserta’s clothes store on Haight. They all became friends. Nobody was a celebrity in those days. The neighborhood thought it owned the bands. Everyone took care of one another.

Marilyn was careful about whom she slept with, even in those less discriminating days. But at one point, she took up with a Hell’s Angel, one of the Haight’s irresistible bad boys, who gave her the clap. She didn’t want to go to her ob-gyn, who had made her feel creepy the last time she saw him. So she went to the city VD clinic. It was 1967. Everyone was making love with everyone. And Marilyn knew at least thirty of the young people sitting in the waiting room’s rows of pews. “Phil Lesh from the Dead was there. When I walked in, everyone just burst out laughing.”

In the crush of patients, the city clinic was not taking the time to thoroughly sterilize needles, so Marilyn’s blood sample that day was taken with a dirty needle. She came down with hepatitis C and became so sick that her doctor wanted to put her in the hospital. But she didn’t want to go. Instead she went home, collapsed into bed, and phoned the Dead house and told Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, her closest friend in the band.

Pigpen might have looked like a greasy, badass biker, but he had a heart of gold. He tacked a signup sheet on Marilyn’s front door, and various members of the band and its entourage would take turns bringing her meals and caring for her. Some nights Pigpen slept on her couch. She would wake up from a feverish nap, and there at the foot of her bed would be Pigpen or Lesh or Jerry Garcia, a couple of Hell’s Angels, and the principal from her elementary school, all chatting amiably and watching over her like Auntie Em, Uncle Henry, and the farmhands hovering over Dorothy.

“The Dead were special,” she later said. “They had a real devotion to friendship and care.” She would soon have occasion to repay their generosity.

It took nearly three weeks for Marilyn to feel strong enough to get up from bed. One afternoon in October 1967, she was sitting in a wing chair in her third-floor bay window, soaking up the sun, when she saw a small army of grim-looking men sweep into the Dead house. The neighborhood knew the band as the sweetest of its minstrels, always plugging in and playing for free down on the Panhandle. But to the state and city drug agents who raided the band’s Ashbury Street house that day, the thirteen-room Victorian was the center of a sinister narcotics ring. Boyish and spacey Bob Weir, who was meditating in the attic as the narcs invaded the house, and Pigpen were both dragged off to the hall of justice—though, as it...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- Introduction

- Prologue: Wild Irish Rogues

- Part One: Enchantment

- Part Two: Terror

- Part Three: Deliverance

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Season of the Witch Playlist

- About David Talbot

- Sources

- Index

- Copyright