This is a test

- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

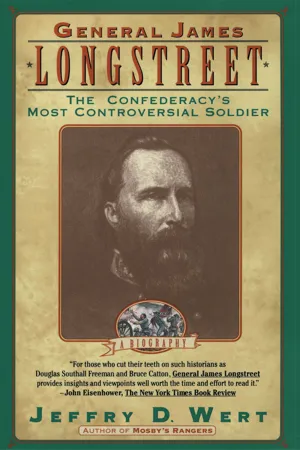

General James Longstreet fought in nearly every campaign of the Civil War, from Manassas (the first battle of Bull Run) to Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chickamauga, Gettysburg, and was present at the surrender at Appomattox. Yet, he was largely held to blame for the Confederacy's defeat at Gettysburg. General James Longstreet sheds new light on the controversial commander and the man Robert E. Lee called "my old war horse."

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access General James Longstreet by Jeffry D. Wert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER

1

SOLDIER’S JOURNEY

The column of men marched up the street in the warmth of a late spring day. Numbering perhaps fifteen thousand and stretching back out of view, the marchers came on without a cadence in their strides or a symmetry to their ranks. Many of them wore tattered old clothes; no two seemed to be dressed alike. At one point in the procession, the shredded remains of a battle flag, held together by red mosquito netting, rose above their heads. The huge crowd of onlookers, however, needed no flag: The sight of these marchers was enough. Everyone sensed that beside each man in the column walked a ghost.

The day was May 29, 1890, in Richmond, Virginia, a time for memories and ghosts. The previous week, the former capital of the Confederacy had been gripped with a “frenzy of Southern feeling,” according to a newspaper reporter. Drygoods stores sold Confederate emblems; a huge Confederate flag draped across the facade of city hall; residents decorated their homes; portraits of the South’s greatest soldier, Robert E. Lee, hung conspicuously throughout the city; and thousands of invited guests and visitors spilled from railroad cars. The city seemingly resonated with the sounds of the past.

The occasion, long planned and anticipated, was the unveiling of an equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee. Sculptor J. A. C. Mercie had designed and created the monument to the former commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, and a coterie of Lee’s lieutenants in the army—Jubal A. Early, Fitzhugh Lee, John B. Gordon, and others —assisted in the preparations. Invitations were extended to former officers, units, and veterans of the Confederacy’s most famous army. In the capital of the long-dead Confederacy, the justness of the Lost Cause and the greatness of Lee’s military genius would be affirmed.

At noon on the 29th, the chief marshal and the general’s nephew, Fitzhugh Lee, mounted on an iron-gray horse, led the parade down Broad Street. Behind him came bands playing music and ranks of young men in uniform, striding forth with the assurance of their years and with the dreams of untested warriors. The crowds of spectators lining the street watched this passage of youth closely, but they were there to see and honor the veterans of Malvern Hill, Second Manassas, Sharpsburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and Appomattox.

As the old soldiers—the youth of an earlier generation who had christened the Confederacy with their sacrifices for four long years—appeared, the onlookers cheered. At the head of the column rode John Gordon, the ramrod-straight Georgian who had led Lee’s army in that final march on the road at Appomattox. Behind him and interspersed among the ranks of the veterans came other generals—Early, Joseph E. Johnston, Wade Hampton, Cadmus M. Wilcox, Joseph Kershaw, Charles Field, Joseph Wheeler, and E. Porter Alexander. The crowd greeted each of them with additional cheering.

But as the carriage of one former general passed, the response of the people increased, rippling along the parade route and rising in volume like a volley of musketry fired from one end of a battle-line to the other. When former soldiers in the column recognized their old chief, they broke ranks, stopping the procession. A few of the men volunteered to lead the horses throughout the route. At the platform near the covered monument, the general, assisted by one of his former aides, stepped from the carriage and took his place on the stand. The assembled veterans emitted a yell, that eerie Southern battle cry that had echoed across numerous bloody fields.

James Longstreet, former lieutenant general and commander of the First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, had arrived. His journey to this place and time had been long. For the better part of the past two decades he had been an apostate, a scapegoat for the majority of Southerners. His record in the war had been vilified and falsified, his devotion to the Confederacy had been questioned. He defended himself in print, but did it poorly and only enhanced the efforts of his detractors. The organizers of this event had not invited him until some of his former artillerymen insisted that he attend as their escort, and he accepted. As he sat down, he knew that to many of his former comrades on the platform he was an unwanted presence.

On this day for memories, however, the veterans of the army remembered James Longstreet as a soldier and saluted him. They knew he belonged there, for he had earned their respect and devotion from the beginning at First Manassas to the end at Appomattox. Although he now looked “old, feeble, indeed badly broken up” to one of his former staff officers, they recalled him as a robust, powerful, and tireless man whose battlefield courage and sincere concern for their welfare had few equals in the army. He had the soul of a soldier, and they never forgot it.

So he sat before the men he cared most about, at the foot of a monument dedicated to the general who had called him “my old war-horse.” It was as it should have been—a day for memories, a day for ghosts, a day for soldiers.1

• • •

James Longstreet was born in the Edgefield District, South Carolina, on January 8, 1821, the third son and fifth child of James and Mary Ann Dent Longstreet. His parents owned a cotton plantation in the Piedmont section of northeastern Georgia near what would become the village of Gainesville. Neither parent was a native of the South Carolina-Georgia border region—James was born in New Jersey; Mary, in Maryland. Both belonged to families whose ancestry in America dated from the colonial period.2

The first Longstreet in the New World was Dirck Stoffels Langestraet, who emigrated to the Dutch colony of New Netherlands in 1657. Three generations later the family name had been anglicized, and on October 6, 1759, William Longstreet, James’s grandfather, was born in Monmouth County, New Jersey. William inherited the independent and roving spirit of the Longstreet males. In the mid-1780s, he married Hannah Fitz Randolph, born on March 23, 1761, the daughter of James and Deliverance Coward Fitz Randolph. The Fitz Randolphs, whose ancestors first settled in Puritan Massachusetts in 1630, had lived in New Jersey for over a century. Following their marriage, William and Hannah moved to Augusta, Georgia, on the Savannah River. Regarded in the family as a “genius,” William was a tinkerer and inventor with a keen interest in steam engines.3

Within two years of his arrival in Augusta, William had constructed a steamboat and launched it on the nearby river. The craft had no paddle wheel, but a series of long poles driven by the engine against the river’s bottom. He utilized the principle subsequently adopted by keelboatmen, but his steamboat was too mechanically complex to be reliable. When he failed to secure local financial backing, he wrote to Georgia Governor Thomas Telfair on September 26, 1790, requesting state funds for his invention. Telfair rejected the proposal, and William’s experiment ended.4

In his letter to the governor, William wrote: “I make no doubt but that you have often heard of my steamboat, and as often heard it laughed at.” In fact, his steamboat had become the subject of numerous jokes and doggerel poetry in Augusta. His fellow townsmen called him “Billy Boy, the dreamer.” But despite being regarded as an eccentric, William served as a city commissioner and as justice of the peace.5

He continued his tinkering with steam engines, eventually building a steam cotton gin in St. Mary’s, Georgia. About 1800, William and Hannah crossed into South Carolina and purchased land for a cotton plantation in the Edgefield District, fourteen miles north of Augusta. They prospered as planters, with William buying a second residence in Augusta that the family lived in periodically until William’s death on September 1, 1814.6

During their thirty years of marriage, Hannah bore five children. James, their eldest son, was born in New Jersey, while the four other children were born in Georgia. Although devoted parents, William and Hannah fostered in their children the family tradition of independence, self-reliance, and a roving nature. Sometime after the family moved to South Carolina, James struck out on his own, heading north and west to the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. There he purchased land and began raising cotton.7

During the next decade James worked his farm and occasionally visited his parents’ home and Augusta. In the latter place, he met Mary Ann Dent. Her father was Thomas Marshall Dent, a cousin of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, and her mother was Ann Magruder Dent. Native Marylanders whose ancestors had settled in the colony in the 1670s, Mary Ann, her parents, and grandparents—George and Anna Maria Truman Dent—had relocated to Augusta in 1812. How long James and Mary Ann courted is uncertain, but they married in 1814, the year William Longstreet died.8

James brought Mary to his growing plantation, and before year’s end she gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Anna. Three years later, in 1817, a son, William, was born. During the next three years, another daughter, Sarah Jane, and another son, John, were born, but both of them died in infancy. Then, in 1820, Mary was pregnant for a fifth time. Probably after Christmas, she traveled to her mother-in-law’s home in South Carolina and there gave birth to the couple’s third son, James. Although the future soldier would be a native South Carolinian, he always regarded Georgia as his home. His mother brought him to that state within weeks of his birth.9

The Piedmont section of northeastern Georgia, where the Longstreet farm lay, retained many vestiges of the frontier area that it had been only a few years before. It was a land of few farms, few inhabitants, and fewer towns amid a sea of forests and wilderness clearings. It was a land that required physical labor, patience, and resilience on the part of the settlers who went there to carve a farm or cobble together a village. It was a land that changed adults and shaped children.

Here the newborn son, named for his father, spent the first nine years of his life. With sister Anna and brother William as guides and mentors, young James romped and explored across the family’s fields and into the nearby woods. Farm chores shared the children’s time with hunting, fishing, riding, and other playful activities. Although young James would not write of his childhood in his memoirs, these early years in northeastern Georgia fostered the characteristics of the future man and soldier. He grew tall, strong, and rugged with a love of the outdoors and of physical activity. From his lineage he inherited independence of thought and self-confidence; from his surroundings, self-reliance, tirelessness, and a work ethic. Although reserved in speech and manner, he learned the value of blunt talk and expressing his opinions in a forthright manner. He possessed little refinement or education.10

By the time James was nine years old, the Longstreet children numbered seven. From 1822 to 1829, Mary gave birth to four daughters—Henrietta (1822), Rebecca (1824), Eliza Parke (1828), and Maria Nelson (1829). The elder James provided well for his growing family. In a region where most of the farmers grew tobacco and corn without slave labor, James Longstreet earned a respectable income with cotton, worked by his modest force of slaves. But with such a number of children, the father had to plan ahead for their future education. In 1830, the father decided that his second and namesake son needed a good education if he was to pursue his father’s chosen goal—admittance to the United States Military Academy at West Point.11

Young James, whom the family called Peter or Pete, spoke often of a military career. Childish dreams of glory filled his head as he read books about Alexander the Great, Caesar, Napoleon, and George Washington. To his practical father, such youthful longings could be gratified with an education at little expense to the family if the nine-year-old warrior gained acceptance to West Point. With this in mind, father and son traveled in the fall of 1830 to Augusta, where James’s younger brother and family resided. Here the boy could live with his aunt and uncle and attend Richmond County Academy, the state’s finest preparatory school.12

The Augusta that welcomed the youthful newcomer had changed measurably since the mid-1780s when grandfather William amused onlookers with his peculiar steamboat. Its population numbered five thousand, making it the second largest city in the state. It bustled with activity, from the numerous commercial establishments along the streets to the noise and sweat found on the Savannah River wharfs. Young James had probably visited the city before, but to live in it, away from his parents, brother, and sisters, must have been daunting for a nine-year-old. Perhaps even more daunting was the knowledge that he would be living with his uncle, Augustus B. Longstreet.13

Of all of eccentric William’s children, Augustus B. Longstreet was the most remarkable. He was even exceptional from the very beginning of his life, weighing a reported seventeen pounds at his birth on September 22, 1790. After the family moved to South Carolina, his father, William, sent Augustus back to Augusta where he enrolled in the Richmond County Academy. A precocious lad, Augustus did not like the rigid atmosphere at the academy and eventually was expelled. In 1811, he entered Yale University as a junior, graduating two years later with a bachelor of arts degree. From New Haven he went to Litchfield, Connecticut, spending over a year studying at Judge Tapping Reeve’s renowned law school. He returned to Georgia and in 1815 was admitted to the bar of Richmond County. His father had died the year before.14

A gifted conversationalist with a keen sense of humor, Augustus drew clients to his law practice. On March 3, 1817, he married Frances Eliza Parke of Greensboro, Georgia. Eventually, Augustus and Frances had three children, a son and two daughters. In 1821, he was elected to the state legislature; the following year, he was appointed a judge on the superior court and given a master of arts degree by the University of Georgia. Elective politics still attracted Augustus, and in 1824 he ran for the United States House of Representatives. During the campaign, however, his son was stricken with an illness and died. A deeply grieved Augustus withdrew from the race.15

Augustus Longstreet was an enormously talented, well-educated, and personable man. His intellect, perception, and humor, combined with an intense earnestness, made him a formidable presence in a courtroom or on a political stump. A devout individual, he even found time to serve as a licensed lay speaker in the Methodist Church. Into such a man’s house, young James Longstreet arrived in the fall of 1830. The nephew would spend the next eight years of his life at “Westover,” his aunt and uncle’s plantation located at the city’s edge. Augustus, Frances, and their two daughters embraced the boy as a member of their family. Although an education at the academy brought him to Augusta, when he departed as a young man, much of the learning he carried with him occurred within the walls of Westover.16

Young James Longstreet entered Richmond County Academy on October 7, 1830. Since 1802, the school had occupied a two-story brick building with attached wings on Telfair Street between Centre and Washington streets. During the fall and winter, the school began at 8:30 A.M and concluded at 5:00 P.M. In the warmth and heat of spring and summer, students reported an hour earlier and stayed an hour later. The only v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- List of Maps

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1. Soldier’s Journey

- 2. Soldier’s Trade

- 3. Manassas

- 4. Generals

- 5. Toward Richmond

- 6. A “Misunderstanding” at Seven Pines

- 7. “The Staff in My Right Hand”

- 8. Return to Manassas

- 9. “My Old War-horse”

- 10. “I Will Kill Them All”

- 11. Independent Command

- 12. Collision in Pennsylvania

- 13. Gettysburg, July 2, 1863

- 14. “Never was I so Depressed”

- 15. “Longstreet is the Man”

- 16. “Nothing but the Hand of God can save Us”

- 17. Knoxville

- 18. “The Impossible Position that I Held”

- 19. Two Roads

- 20. Final Journey

- Photographs

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Photo Credits

- Copyright