- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

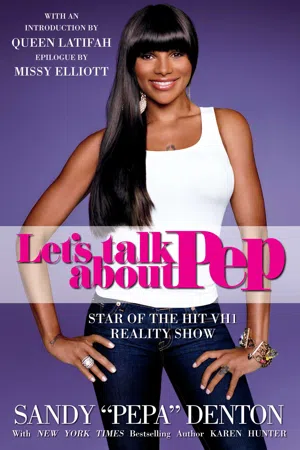

Let's Talk About Pep

About this book

From Sandy “Pepa” Denton—rap legend and outspoken reality TV star—comes the juicy tell-all in which she talks about sex, music, life, love, fame, and so much more.

The spiciest ingredient in the legendary rap group Salt-N-Pepa, fans know Sandy Denton as Pep, or Pepa, the fun-loving half of Salt-N-Pepa. But behind the laughs and the smiles is a whole lot of pain, and for the first time in Let’s talk About Pep, she candidly talks about her troubled childhood, surviving abuse, her first encounters with Cheryl “Salt” James, instant success, her failed marriages and escape from domestic abuse, and her triumphant comeback on reality shows like The Surreal Life and The Salt-N-Pepa Show.

Filled with surprising insights, outrageous anecdotes, and celebrity cameos—including Queen Latifah, Martin Lawrence, Janice Dickinson, Missy Elliott, L.L. Cool J, Ron Jeremy, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopez, and many others—Let’s Talk About Pep offers a fascinating glimpse behind the fame, family, failures, and success...and into the faithful heart of a woman who will always treasure the good friends she found along the way.

Every bit as captivating and provocative as her Grammy Award-winning music, this story reveals the real Pepa—upfront, uncensored, unstoppable—a true pioneer, survivor, and inspiration to women everywhere.

The spiciest ingredient in the legendary rap group Salt-N-Pepa, fans know Sandy Denton as Pep, or Pepa, the fun-loving half of Salt-N-Pepa. But behind the laughs and the smiles is a whole lot of pain, and for the first time in Let’s talk About Pep, she candidly talks about her troubled childhood, surviving abuse, her first encounters with Cheryl “Salt” James, instant success, her failed marriages and escape from domestic abuse, and her triumphant comeback on reality shows like The Surreal Life and The Salt-N-Pepa Show.

Filled with surprising insights, outrageous anecdotes, and celebrity cameos—including Queen Latifah, Martin Lawrence, Janice Dickinson, Missy Elliott, L.L. Cool J, Ron Jeremy, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopez, and many others—Let’s Talk About Pep offers a fascinating glimpse behind the fame, family, failures, and success...and into the faithful heart of a woman who will always treasure the good friends she found along the way.

Every bit as captivating and provocative as her Grammy Award-winning music, this story reveals the real Pepa—upfront, uncensored, unstoppable—a true pioneer, survivor, and inspiration to women everywhere.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Chameleon’s Curse

I WAS BORN IN JAMAICA. My earliest memories are of being on my grandmother’s farm in St. Elizabeth’s, which was considered the cush-cush or upper-class section of Jamaica, between Negril and Kingston. We lived in what they called the country, and I just remember running free and not having a care in the world. I didn’t come to the States until I was about six. That’s when life became complicated.

I was the youngest of eight. The baby. My mother said I was the cutest baby she had ever seen. When I six months old, she entered me in this contest to be the face of O-Lac’s, which was Jamaica’s version of Gerber baby food. They were looking for a fat, healthy baby, and I won the contest. I was the face—this smiling, fat, toothless baby—on O-Lac’s for years. I guess I was destined for stardom.

My parents moved to the United States when I was three. One by one, each of my sisters left, too. I know that my father had a government job in Jamaica. I don’t know what happened with it. I just remember talk of “opportunity” and “education” in America.

In Jamaica, you had to pay for education after primary school. And getting an education was big in my family. So maybe that’s why they left. I never asked. You didn’t ask questions when I was growing up. My family was traditional, and kids didn’t ask adults questions, you just accepted things—whatever those things were.

I ended up being in Jamaica with my grandmother and one of my older sisters. My parents would come back from time to time, but I was there for a couple of years before they finally moved me to the States, too.

I loved my family, but I never quite fit in with them. I was always a little bit different. My sister Dawn was the rebel, the black sheep. I watched how she used to get beatings—I mean real beatings, not some little old spankings—and I didn’t want any of that. My parents, mostly my father, tried to beat the rebellion out of Dawn. It didn’t work, though. It might have made her more rebellious.

By the time I got to the States, she was hanging out with the wrong crowds, staying out way beyond the curfew and trying to sneak in the house and getting caught. She used to steal my father’s gun. She would fight. And eventually she turned to drugs. But that was my girl! I looked up to Dawn. I just didn’t want to suffer any of those beatings, so I was a “good girl.” I did what I was told—as far as they knew—and I stayed out of trouble. But I was always a little different.

When I was on that farm in Jamaica, I would get into all kinds of trouble. One day I remember I got ahold of a machete. I was only like five years old. Don’t ask me how I got it or where I got it from, but I had this machete and a bucket. I went around the farm looking for lizards or chameleons. They had all kinds of creatures on this farm, but there were a lot of chameleons. I was fascinated by them, watching them go to a green plant and turn green, then to the ground and turn brown. I walked around looking for them, and I would chop them in half and throw them into my bucket.

By the end of the day, I had a bucket full of chopped-up lizards. My sister came out and saw what I was doing and she scared the hell out of me.

“What is that you’re doing?!” she screamed. “Dem lizards gwon ride ya.”

She was telling me that the lizards were going to haunt me. That my doing that had unleashed some kind of curse.

“Dem gwon ride ya!” my sister kept saying in her Jamaican patois.

Well, they did ride me. As I got older, a lot of my friends would tell me, “You’re such a chameleon.”

It was true. I was real good at blending in. I was good at taking on whatever was around me. If I hung out with thugs, I would be a thug. If I hung out with a prince, it was nothing for me to become royalty. My ability to fit in has been a blessing, but also a curse.

The very thing that got me into Salt-N-Pepa—going with the flow and doing what I was told—was the same thing that got me in a lot of bad situations. Being a chameleon or just going with whatever wasn’t good for me. It allowed me to put up with things I shouldn’t have put up with. It allowed me to be with people I should not have been with because I wasn’t able to just be myself and say no or walk away. It never let me ask, “What do I want out of life?” It never allowed me to really think about me and my needs first.

I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be accepted. I wanted people to like me.

CHAPTER TWO

Coming to America

IT’S EASY TO GET LOST in a big family—especially as the youngest. I have six sisters and a brother. And they all had their roles in the family long before I came along.

There’s my brother, Bully, who was the only boy. I didn’t really get too tight with him because he was a boy and was so much older. He was out of the house by the time I came from Jamaica. I can’t tell you exactly how old Bully is—actually, I’m sketchy on the ages of most of my siblings. You see, my mom was really big on not telling her age. So she used to get on all of us kids about telling our age. Because if you knew how old we were, you could probably figure out how old she is. And she wasn’t having that.

To this day, I don’t know how old my mother is because she refuses to tell anyone. She won’t even let her grandchildren call her grandma. If they even try, she will tell them, “Watch your mouth!” And she means it.

So I grew up in this kind of Hollywood family where everybody lied about his or her age.

I know Bully and Fay are the oldest, but I don’t know who is older nor exactly how old either one is. I just learned never to ask. Fay is a lot like my mom. She likes to have a good time and to party. She’s a lot of fun. She lives in Florida and has her own business. Then there’s Jean, the bossy one. If you tried to go into her room, she would yell, “Get out!” But she was also the sister who used to take me to the circus, to the Ice Capades, and to Broadway plays when I was little.

I’m not really tight with Fiona, who is next in age. She had moved out and on with her life by the time I came into the picture. She was always into her own thing. She and Patsy were tight. Patsy is the adventurer in the family—not like me (who will try just about anything on a dare). Patsy really loves the outdoors—camping, hiking, nature, the woods, that kind of thing. If you’re hanging with Patsy, she will have you doing outdoor activities or going to a science museum or a cave or something. And she will be feeding you something organic—some vegetarian lasagna. You’re definitely going to eat your vegetables hanging with Patsy. She even grows her own in her garden.

Then there’s Bev. She’s the lawyer and the family organizer. She plans all of the trips (we try to take about two a year as a family), and all of the dinners for everybody’s birthday. That’s Bev’s thing.

Then there is Dawn. The rebel. My protector.

Those are the Dentons. All of them moved to the States before I did. As I mentioned, I spent my first six years on a farm in Jamaica with my grandmother while my family settled into life in the States. Both of my parents were strict and demanding—especially my father. He didn’t take any crap and he expected the best from all of us.

“That’s what Dentons do,” he would say when one of my sisters brought home straight A’s. And they all did. The Dentons made the honor roll. The Dentons worked hard. My parents’ hard work allowed them to give us a pretty good life. I don’t remember ever wanting for much growing up. Some of it had to do with having older siblings who also worked and would spoil me. Yes, I was the baby.

Moving to the United States was a culture shock for me. I went from this rural farm in Jamaica to the big city. We lived in Jamaica, Queens, of all places. My parents had the biggest house on Anderson Road—and we needed every bit of that space. Our house was like a boardinghouse. Any relative or friend who didn’t have a place to stay, stayed with us. There were my six sisters, me, my mother and father, and whoever else needed a place to stay.

We used to play musical rooms in my house. I started out on the second floor with four of my sisters. But by the time I was eight, I was in the attic with my sister Dawn. My father had converted our basement into two bedrooms, and people were living down there.

Our house, including the attic, had four floors. And the house was always noisy. You could get lost in that house for days and no one would notice you because there was always something going on. Our house was alive.

My mother loved to party. That’s probably where I got it from. My mom was always glamorous and fly, and she loved having people over and entertaining. She is quite a character. She would tell people about themselves in a minute (and she still does!). People are afraid of my mother’s mouth. But you better not say anything to her.

My mom worked hard and partied hard. On the weekends our house was turned into a nightclub. She would host house parties where she and my dad would sell liquor and dinners, and there would be reggae and R&B blasting. The house would be rocking. It started off small with just a few friends and family members, then as word spread, people from the neighborhood would come and bring friends. Every week the party would be bigger and bigger.

I used to love it. To see all of those people laughing and dancing and having fun was a thrill. I would sneak downstairs and just watch. I couldn’t wait for the day that I could be right there in the mix. I couldn’t wait until I was grown.

I was the baby. And was always treated like the baby. Children were to be seen and not heard. My parents were from the old school. So I kept quiet and out of the way. That’s how I was raised. I was always respectful—even to my sisters. Even Dawn, who was about six years older than I am, got respect. I looked up to her. My older sisters always took care of me, and I just naturally treated them with respect.

My sisters were more like my aunts, and many of them acted as if they were my mother (a couple of them had children around my age). I was as respectful with them as I was with my parents. If they told me to do something, I was mindful and would do it and wouldn’t talk back to them. I never argued. To this day, they get that respect. My friends think it’s weird how I treat my sisters, but that’s how our family is.

I was like a chameleon even in my own house. I just tried to blend in, not make any waves, not cause any trouble.

That’s not to say that I didn’t get into any trouble. Before our basement was converted into bedrooms, I used to spend a lot of time down there playing by myself. I found some matches, and just like that time back on that farm in Jamaica, I guess I was bored and fascinated. I had seen quite a few people light a cigarette with these matches, and I wanted to figure out how to do it.

So there I was striking away. I would light one, then just toss it to the floor, afraid of burning my fingers. A bunch of blankets were in the corner of the basement, and I was lighting these matches and a couple of them landed on the blankets. The next thing I knew, the blankets caught on fire. I panicked and ran. Thank God the whole house didn’t catch on fire and someone came and put it out before it got out of control.

I ran and got a bunch of toilet paper and put it in my pants. I just knew I was going to get a beating. My mother looked at me, and I must have looked so pitiful that she said, “I’m not even going to beat you.” I couldn’t believe it.

My mother was a beater. She beat everyone. My father didn’t beat us often, but when he did, it was bad. I never wanted to do anything to get a beating from either of them, especially my father. My father would beat my sisters, my cousins. Whatever kid that was in the house and didn’t behave got a beating. And he would beat you with anything—extension cord, belt, switch, paddle.

That was love in my home. No one ever said, “I love you.” That just wasn’t the way my parents were. There were no hugs and kisses. There was a lot of discipline and high standards. And I grew up thinking that everyone’s household was like that.

When I got older and saw how other people interacted with their parents and heard their parents say, “I love you,” I thought it was the strangest thing. Cheryl used to tease me a lot. She came from one of those “I love you” households. And she used to try to get me to be affectionate. She would say, “Give me a hug!” just to mess with me because she knew that would make me uncomfortable. I guess Cheryl broke me down. Either that or I just got used to it. I liked how it made me feel, too.

To this day, I’m one of the most affectionate people you will meet—especially with my kids. Not a day goes by that I don’t tell my son and daughter that I love them, and they tell me that, too. It’s just how we are. That’s my rule. And my nieces and nephews gravitate toward me because they know Aunt Sandy will love them up.

But I understand my parents now. That’s not how they were raised. Where they came from, showing affection just wasn’t done. I didn’t know better when I was younger, I just thought that was how people were.

My mother was funny, though. She had a funny way about her but I knew she loved us. She just had a different way of showing it.

I can’t imagine raising so many kids and keeping it all together and still wanting a certain kind of life. I know she sacrificed a lot to have us. My mom is a dynamic woman.

She used to tell us all the time that if she didn’t have us children, she would have been a politician or something. She had big dreams. She was really good at laying down the law and keeping the peace—by any means necessary. My mom was the politician in our home—solving all problems, keeping everyone together, and taking care of the household. And she was the neighborhood politician, throwing parties and being the life of the party. People loved being around my m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction by Queen Latifah

- Prologue: Expression

- Chapter One: The Chameleon’s Curse

- Chapter Two: Coming to America

- Chapter Three: “And You Better Not Tell!”

- Chapter Four: Heaven or Hell

- Chapter Five: Daddy’s Girl

- Chapter Six: Salt-N-Pepa’s Here

- Chapter Seven: My Scarface

- Chapter Eight: Big Fun

- Chapter Nine: Give Props to Hip-Hop

- Chapter Ten: Hurby Hate Bug

- Chapter Eleven: Somma Time Man: Tah Tah

- Chapter Twelve: Partying like Rock Stars

- Chapter Thirteen: Naughty by Nature

- Chapter Fourteen: Whatta Man

- Chapter Fifteen: The Nightmare

- Chapter Sixteen: Beauty and the Beat

- Chapter Seventeen: Joined at the Hip No More

- Chapter Eighteen: My Surreal Life

- Chapter Nineteen: Salt-N-Pepa’s Here Again!

- Chapter Twenty: Blacks’ Magic? God’s Gift!

- Chapter Twenty-one: Celibacy: Very Necessary!

- Chapter Twenty-two: Do You Want Me? This Is What You Have to Do

- Chapter Twenty-three: Pep Talk

- Epilogue by Missy Elliot

- Photographic Insert

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Let's Talk About Pep by Sandy Denton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.