![]()

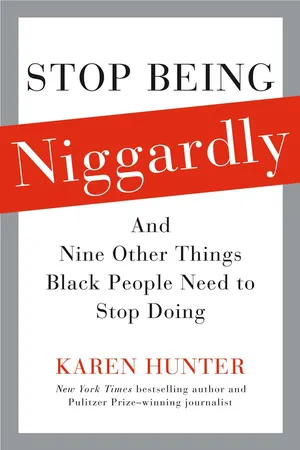

TEN

Stop Being Niggardly

Niggardly, adj. (often offensive): not generous,

stingy. Meager. Scanty. Cheap.

NOW WHAT DOES all that I’ve written so far have to do with being niggardly? I’m glad you asked. Oftentimes when we start a business or make any major decisions in our lives, we do it in a niggardly manner, meaning we cheat ourselves. We’re stingy with us. We don’t properly plan, we don’t gather the information we need, we think small, and we execute at an even smaller level.

I could easily have started a publishing house by printing up some books for people and putting them out into the marketplace. I might even have sold a few. But would that model ever compete with what I envisioned, which was to have a house that long after I was gone would be mentioned in the same breath as Simon & Schuster and Random House?

To be big, you have to think big.

Simon & Schuster was founded by Richard Simon and Max Schuster, two guys who started publishing crossword puzzles. There was Nelson Doubleday and Henry Holt and Alfred Knopf.

These men all had a vision to start a publishing house, and they did it. But they had help. All of them. They had friends and family—people who looked like them—who helped fund their dream.

What most frustrated me about starting my publishing house was that despite so many resources—Earl Graves, Ed Lewis, and a dozen or so multimillionaire Wall Street types (who hadn’t lost their shirt when the markets crashed)—no one saw value in my venture. I told them all what I was doing—not what I was planning to do, but what I was actually doing—and not one offered to help. Not one.

I thought it was interesting considering that not a single black major book-publishing house was in the marketplace. You would think someone would at least offer his or her business expertise. Not one.

Black folks have often been accused of being crabs in a barrel. As soon as one tries to get out, the ones at the bottom grab on, making sure that the one that is almost out doesn’t make it to freedom. And those who make it out seem to try to shut the lid to make sure the rest stay in their place.

Niggardly.

Beyond business, people are stingy with themselves and the things around them.

I tithe. I understand it was a law from the Old Testament and many Christians today don’t think that it’s still relevant. I don’t tithe to be legalistic. I tithe because giving opens up my world. Whether I tithe 10 percent to my church or I use my offerings to help buy medicine for someone suffering from cancer who doesn’t have health insurance or I help put a kid through school, the reward of that giving is inexplicable.

During one of the most trying periods of my life, I made a commitment to tithe. The way I looked at it, if God allowed me to make whatever I made and all He asked for was 10 percent, then that was the least I could do. I faithfully tithed, even though, as I looked at my bank account at times, it made no sense.

During this period I was offered a book deal to do Mason Betha’s story. It was right on time, because I don’t think I could have covered my bills another month. With that check, I paid off my car and freed myself from some debt. I believe that it was my spirit of giving, even when money was tight, that opened me up to also receive opportunities from others.

I have a friend who has an aunt who always seems to have money. She was the wealthy one in a poor family, and oftentimes her family would turn to her when they needed something. She was so stingy that she rarely, if ever, lent or gave money to her family, even when in need. When she did lend, which was rare, she tortured the borrowers to the point that they wished they had never borrowed from her.

My friend was in her final year of school and needed $1,200 for tuition to remain registered. She would have been the first person in the family to graduate from college, and her mother didn’t have the money. They scraped together $700 and went to the aunt for the final $500. The aunt said no.

Fast-forward fifteen years, and that same aunt had a stroke and had to depend on those same family members to take care of her. Guess what? Nobody was there for her. Not her children. Not her grandchildren. My friend visits her aunt from time to time and provides her with the only source of comfort in her life.

There are practical reasons to not be stingy, and it’s not just about money. You can be stingy with yourself and suffer as well.

I have another friend, Ted, who was raised one of ten in a family with little money.

“Food was scarce,” he said.“We couldn’t wait for holidays because then we would be sure of getting something to eat. Some of us would hide our food so that we would make sure to have some.”

Fast-forward into adulthood. Ted was hanging with one of his friends. They would often go to dinner, and his friend would offer him food off his plate every time. Every time Ted would accept.

“One time, after about a year of hanging out, my friend finally said something to me,” Ted said.“He asked me why I had never offered him anything off of my plate. I never thought about it. I guess, considering my upbringing of never having enough, it never dawned on me to offer anyone food. I’m glad he said something and brought it to my attention because I’ve never let that happen again.”

For Ted, not offering food was a by-product of growing up in lack, in a niggardly state. If his friend were a different person, he could simply have deemed Ted selfish. But in realizing this and changing, Ted enjoys much better relationships with his friends.

I sponsored a golfer in 2008. I met him in Florida on a golf course where he worked fixing carts. In his spare time, he would give lessons for free and for small change. The course stopped him from doing so because they said he was taking money away from their real pros.

I decided that I would help him get his pro card so that he could give all of the lessons he wanted and get the money he deserved. I discovered that this man was really good, and I had a vision of his becoming a champion on the senior tour. Mr. James was sixty-eight years old and had while growing up in Alabama learned to play golf with a makeshift club made from an old hanger and some duct tape. He had caddied for some of the best golfers in the country and had played with and beaten the likes of Jim Thorpe. Mr. James was a modern Bagger Vance. While I had a grand vision for him, he didn’t have one for himself.

I gave him $2,500, which was the amount he needed to attend qualifying school to get onto the tour, or at the very least get his pro card so that he could teach. Instead, he used the money to play in small tournaments. He didn’t think he was ready for Q school and wanted to“warm up” in a few local tournaments. The first tournament in which he played, he won. He got $5,000. Under our agreement, I was entitled to my investment back. He cried broke and said he needed the money.

No problem. He was scheduled to be in two more tournaments, which I was certain he would win. I would get my money back, and he would have enough to enter Q school and start his journey toward making history as the oldest person to qualify for the pro tour.

He came in second in the next tournament, bagging $3,000. Mr. James dropped out of the next tournament because he was angry that they lowered his handicap, meaning he wouldn’t have as much of an advantage. Well, that’s what happens when you play well and win. Instead of being energized by his success, it seemed to scare him. He wouldn’t play in any more tournaments and had within two months spent all of his earnings.

Not only did Mr. James not end up on the senior tour, he never got his pro card to give lessons, and he spent every dime he won on things that didn’t enrich his life. He didn’t put a down payment on a home to move out of the ghetto. He didn’t get his teeth fixed (he had several missing in the front), which would have given him more confidence to interact with people. He didn’t get rid of his broken-down hoopty for a better, more reliable car. He was no better off because he was not only niggardly with himself—having a stingy view of his future—he was also niggardly with me, not honoring our agreement and following through with what he’d said he was committed to doing.

Today, Mr. James is worse off than when I met him. The golf course cut down on his hours (he could have replaced that income by giving lessons), his car is constantly in the shop (requiring money and his taking days off to get it fixed), and he tasted success and lost it (which often is more difficult to deal with than having never tasted success at all).

Being niggardly or cheap or stingy guarantees you will always be in lack. You may keep your money, but I bet you will have shorts in other areas of your life.

So stop being niggardly! Stop cheating yourself out of the blessings you are supposed to have by focusing on the things you don’t have, by looking at what others have and are doing instead of being excellent and following your own path and purpose.

With that message, I hand these pages over to a woman I have grown to respect immensely for her wisdom and insight.

The next section of this book is devoted to celebrating the power of black people. That’s how I look at it. It’s an action plan to being the best we can be as a group. This is important not as some black-power excursion, but because our nation is made up of many groups of people—some who willingly came to this country for a better life, and others who came here in shackles—who want the American Dream.

Each of us, from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds, can have this by focusing first on being the best we can be individually. Once we take care of home, we can focus on contributing to the greatness of the country.

I look at black America as home, and we have some housecleaning to do. If we individually follow the simple rules given to us by Nannie Helen Burroughs, we will be a whole lot closer collectively to realizing that dream.

Twelve Things

the Negro

Must Do

by Nannie Helen Burroughs (with commentary by Karen Hunter)

![]()

INTRODUCATION

Who Is Nannie Helen Burroughs?

I CAME ACROSS Nannie Helen Burroughs by accident in 2002. Actually, a listener of my morning talk-radio show sent me her essay Twelve Things the Negro Must Do. What struck me initially was how bold her statements were. She wrote this in the 1890s when not just blacks, but women, had no voice. Here she was telling it like it is, saying the things that would ultimately give her people power—not over anyone, but power over themselves and their own lives.

What Burroughs understood more than a hundred years ago, which many people still don’t get, is that freedom is not something someone can deny you. True freedom and true success and prosperity are generated within a people. Having standards and a commitment to excellence can defy any attempt to discredit or discriminate.

What Burroughs understood more than a hundred years ago is that if a group committed themselves to some simple truths and living those out, they wouldn’t need anyone. If they could be self-sufficient and self-reliant, then even a racist America, one bent on separating and dividing, would have no choice but to acknowledge them or let them be.

So Burroughs, born in 1879 in Orange, Virginia, the eldest daughter of John and Jennie Burroughs, both born into slavery, was very much free. She learned that education—knowledge—was power. After the death of her father, her mother took Burroughs and her sister to Washington, D.C.

She graduated from high school with honors in 1896 and received an honorary masters from Eckstein-Norton University in Kentucky. She wanted to become a teacher but was denied a position by the board of education in the District of Columbia.

Instead of wallowing in self-pity, she used the power of words to empower others. Burroughs moved to Philadelphia and became associate editor of a Baptist newspaper, the Christian Banner. She moved back to D.C., more educated and more prepared. She expected to get an appointment this time after receiving high ratings on her civil service exam. Again she experienced disappointment when she was told there were no jobs for a“colored girl.”

Did she cry racism? Did she complain and whine about the white man keeping her down? Did she let the exclusion keep her from her goal?

No.

She decided to start her own school, which allowed her to have a greater impact on a larger number of students.

“My school would give all sorts of girls a fair chance,” she would say.

Burroughs didn’t have much money, but she had heart and drive. She took a job as an office-building janitor and later took a position as a bookkeeper for a manufacturing company. She then accepted a position in Louisville, Kentucky, as a secretary for the Foreign Mission Board of the National Baptist Convention. She saved enough to open in the early 1900s the Women’s Industrial Club, which offered short-term lodging to black women and taught them basic domestic skills. The organization also provided moderate-cost lunches for downtown office workers.

Later Burroughs started to hold classes, for ten cents a week, for club members majoring in business. In 1907, with the support of the National Baptist Convention, Burroughs began coordinating building plans for the National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls, located in Washington, D.C.—the very city that had denied her access to their classrooms.

Burroughs’s school opened its doors in 1909 with her as president. Her motto:“We specialize in the wholly impossible.”

The wholly impossible!

Burroughs understood that through education, desire, faith, and sheer will, all things were possible. Her curriculum was designed to emphasize practical as well as professional skills. Her students were taught to be self-sufficient wage earners as well as“expert homemakers.” She believed her duty was to see that an industrial and a classical education be simultaneously attained.

She demanded excellence. It was said that grammatical errors were physically painful to her, and she required courses on a high school and a junior college level to develop her students’ language skills.

The National Trade and Professional School also maintained a close connection between education and religion. Its creed, stressed by Burroughs, consisted of the three B’s:“The Bible, the bath, the broom—clean life, clean body, clean house.”

Burroughs also understood that for people to have a real future, they must understand from whence they came. History—black history—was another foundational piece stressed by Burroughs at her school.

Today, Burroughs is part of history. In 1964, the National Trade and Professional School was renamed Nannie Burroughs School. In 1975, the then mayor of D.C., Walter E. Washington, proclaimed May 10 to be Nannie Helen Burroughs Day in the District of Columbia.

Burroughs died in 1961, but what she accomplished and her words of wisdom live on. With respect and a deep, abiding sense of history I give you Twelve Things the Negro Must Do.

Let’s honor Nannie Helen Burroughs by making her words become flesh by incorporating them into our daily lives.

![]()

ONE

The Negro Must Learn to Put First Things First. The First Things Are: Education; Development of Character Traits; a Trade and Home Ownership

BURROUGHS

The Negro puts too much of his earning in clothes, in food, in show, and in having what he calls“a good time.”

Dr. Kelly Miller said,“The Negro buys what he wants and begs for what he needs.”… Too true!

HUNTER

This first Burroughs missive almost needs no commentary. She incorporates so much in one sentence. Putting first things first. Some could say put God first (well, that goes without saying and we will definitely get to that). But what I think Burrough...