This is a test

- 339 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

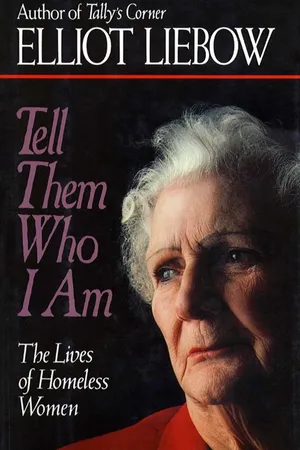

Tell Them Who I Am

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

He observes them, creating portraits that are intimate and objective, while breaking down stereotypes and dehumanizing labels often used to describe the homeless. Liebow writes about their daily habits, constant struggles, their humor, compassion and strength.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Tell Them Who I Am by Elliot Liebow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

APPENDIX B Life Histories

Note: The following life histories have been greatly condensed from the original tapes. Because I waited a few months before taking life histories, and because I also often waited for the women to volunteer them, most of the histories are of longtime homeless women, perhaps because they or their families were especially dysfunctional. They include most of the women I came to know best. These histories, then, are not offered as a sample of the population of homeless women I studied. I include them for the sake of completeness, and for whatever intrinsic interest and value they may have for the reader.

Abigail

Abigail, 27 years old and white, is of average height and weight. Her hair is black, thick, and wiry. Her teeth are very bad and she is diabetic. Abigail gives an impression of competence and mental quickness.1

Abigail was born and raised near Trenton, New Jersey. She was the fourth of five children by one reckoning, the first and only child by another. Her real mother, she says, was her private nursemaid and her father’s mistress who lived three miles down the road from the family house, although Abigail didn’t learn the identity of her real mother until two years ago. Abigail believes her father was a draftsman. Her “adopted” mother sometimes worked as a saleswoman in a clothing store. Her father was Jewish; both her mothers were Christian.

When Abigail was one year old she was hospitalized for removal of a cancerous kidney. After surgery, she left the hospital and walked the three miles to her “real” mother’s house. Her real mother had a beautiful vegetable garden but someone was stealing all the vegetables. Abigail set a trap for the thief and caught him. She took the prisoner before her mother. “Delores, this is our vegetable thief. Vegetable thief, this is my nursemaid, Delores.” Eddie, the thief, couldn’t believe Abigail was only one year old. He thought she was a 15-year-old midget. By a remarkable coincidence, Eddie was to become the father of Judy, who, in turn, was to become Abigail’s best friend in the shelter years later.

When Abigail was four, her father contracted brain cancer and his wife divorced him “because he wasn’t a whole man.” Abigail was “my daddy’s little girl” and begged him to take her with him, but of course he couldn’t. Her adopted mother didn’t like independence in children and Abigail had long had “a mind of my own.”

Abigail’s mother remarried months later. Abigail’s new stepfather may have been her father’s uncle. He worked in a brewery and had “Pabst” printed on all his work clothes. Abigail liked him a lot.

Abigail did poorly at school but “school was the main part of my life. I dreaded staying home…I enjoyed school only for the reason I was out of the house.”

When Abigail was 15, the family moved to southern California. There, at school, she did drugs—mainly pot, sometimes speed—and was introduced to sex. Just before she was 16, she quit school. Somewhere about this time—1976—the whole family moved to a rural commune of some 1,200 persons. Abigail remained there about two years, picking and canning fruit. In 1978, she “figured I wanted to be out in the world again” and returned to New Jersey to live with a boyfriend. There she worked the graveyard shift at Dunkin’ Donuts; her boyfriend was a painter/carpenter. After six months in Trenton they returned to southern California. In November 1978 Abigail discovered she was pregnant.

The following spring, five or six months into her pregnancy, Abigail was “put out” by her alcoholic, woman-beating boyfriend. She went to live with her mother for a few months, then moved back to the farm/commune to have her baby in July. Over the next couple of years, Abigail and her baby lived briefly with her grandmother in New Jersey and on and off with her boyfriend, sometimes in New Jersey, sometimes in California, living on AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) and food stamps. Meanwhile, she got her high school equivalency certificate and made several attempts at going to community colleges in California but “it was a little too difficult for me.” It was during this period, too, that Abigail neglected her insulin shots and had to be hospitalized. Her baby was put in protective custody in a foster home until Abigail’s release from the hospital.

In November 1982, Social Services made an unannounced visit to her apartment, found it messy and otherwise wanting, and took her baby from her. Abigail believes her brother and mother set her up for this. She recalls the separation: “I was watching the car go and she was crying and trying to get out of that car and I was crying and waving to her and I called her name and she called mine. From that time on, I haven’t seen my baby.”2

Abigail then met a young man working with a carnival that was passing through town. They moved north together to Sacramento with the carnival, and there they stayed from December 1982 to May 1983, when they were evicted for nonpayment of rent. Abigail called her brother, then living in the D.C. suburbs. He sent her a plane ticket and she flew to Washington to live with her brother and his wife and their two children.

In January 1984, Abigail met Judy at a vocational training program and they became bosom buddies. When Judy left her parents’ home in July of that year and had no place to go, she moved in with Abigail in the basement of Abigail’s brother’s house. From this point on, Abigail and Judy had a joint history.3 Asked to move out of the house two months later, they made a pilgrimage to Indiana with the intention of meeting their make-believe lovers, two real-life members of a Christian rock group, the Pente Kostals; tracked down by Judy’s father, they were shipped back to the D.C. area after three days. Unwilling to meet the conditions laid down by Judy’s parents or Abigail’s brother for returning to either household, the two women went to the Crisis Center which referred them to The Refuge.

Betty

Betty is white and 50 years old. She looks older, perhaps because of her rimless glasses. She is of medium build, but her upper arms are exceptionally fat, forcing her to wear a cape and loose-fitting blouses rather than tailored garments. Betty looks very distinguished and this appearance, together with her assertive carriage and way of speaking, suggests to newcomers that she is an important visitor if not the director of the shelter.

Betty was born in a small town in Virginia. Her parents separated while she was a small child. She does not remember her father but knows he was a laborer. When she was five or six, Betty, her seven-year-old sister, and her mother moved to Washington to live with her mother’s sister in a hotel in a rundown section of the city. Betty’s aunt worked for the phone company and Betty remembers lots of parties and drinking in their apartment in that period. A short time later, when she was perhaps seven, her mother remarried. Betty’s stepfather was a cab driver and her mother a sometime waitress. Both parents were heavy drinkers and the family moved a lot, staying mostly in downtown D.C. Money was always in short supply and Betty wore only hand-me-downs from her sister, but their stepfather always made certain that the family had enough food. She called her stepfather Daddy.

Although she liked school, Betty found everything except reading difficult. She enjoyed Black Beauty and Little Women and “doggy stories and horses and things.” She sang in the glee club and was liked by the other kids.

Betty did not get along with her sister or mother. In the evenings, on the front steps, “I used to daydream, even though it was nighttime, about how it was going to be for me when I got away from my family—all those people who made my life miserable.” With no encouragement from her parents, Betty regularly attended Sunday School at a local Baptist church. (“I’ll never forget how good I felt when I went to Sunday School.”) She participated in children’s activities sponsored by the Salvation Army, “and this also saved my soul.” For a while, Betty had a part-time job preparing a cup of tea and two pieces of toast every evening for an elderly woman in the neighborhood. She liked that very much. “To this day, you know, I enjoy taking care of elderly people.”

At 16, in the 10th grade, Betty quit school. “I wanted nice clothes. I wanted money to go out with my friends—to stop after school in some soda place and have a soda with my friends.” She went to work for an H. L. Green 5&10 and was regularly embarrassed when “my mother waited out front every payday. She took half my paycheck.” If Betty protested, she was “an ungrateful brat.”

Betty was briefly engaged to a military policeman she met in a beer joint. “He was so handsome in his uniform and I was a beautiful young lady at the time.” Despite the engagement, Betty “didn’t cut myself off socially altogether, OK? But I was the type of woman who didn’t go to bed with just anybody.”

When she was 18, Betty moved out to live with a girlfriend in a trailer and “we partied almost every night, my girlfriend and me.” About a year later, they argued and Betty returned to live with her parents, continuing to pay rent there.

Betty left the 5&10 to work in the record department of Hecht’s, a large department store where she remained almost five years. She loved the job and the free records and dinners she got from record salesmen. She also took a part-time job as a waitress in a bar and grill. There she met Richard, a truck driver 15 years older than herself, and “of course we messed around, OK?” Betty was soon pregnant, but they couldn’t marry because, as Richard had forgotten to tell her, he had a wife and children somewhere in Virginia. Betty moved in with him and stopped drinking and smoking for the duration of her pregnancy. She had her baby in 1959, and Richard doted on the child. They led such a normal life “that I forgot we weren’t married.” Betty and her mother reconciled. From the moment Betty’s mother saw the baby, “it was Grandma all the way.”

Betty and Richard had occasional fights. They drank regularly and heavily. They graduated from beer to hard liquor (“seven and seven—7-Up and Seagram’s 7”), and from half a pint to a fifth a day. Soon they were confirmed alcoholics.

From here on, the story is not too clear, even now. Richard begins to miss a lot of work. For a while, his family helps with rent and groceries. Betty discovers she has diabetes but goes on drinking. She is hospitalized for a gall bladder removal and goes on drinking. The years pass—maybe five or six—and the family experiences repeated evictions. Richard works off and on with the same firm but has so many drunk driving charges he can no longer drive a truck and is assigned to some kind of inside work. Betty spends her days drinking and watching soap operas. She falls down a flight of stairs and breaks one or more vertebrae in her back. Later, she is hospitalized again for something or other and returns home to find all their furniture on the street. The family breaks up. The daughter, maybe 11 or 12, goes to live with Betty’s mother and Betty goes to live with a girlfriend, with Richard bringing her a few dollars occasionally. Betty and Richard get together again and move in with Richard’s sister, but this arrangement is shortlived. Richard inherits a couple of thousand dollars from the sale of a family farm, and he and Betty move to a suburban motel and settle in for some serious drinking. “Every now and then we would eat.”

The inheritance spent, Richard leaves, Betty is hospitalized again, then gets a live-in job with an old woman through Operation Match and quickly loses it. Over the next many years, Betty makes her way, sometimes on public assistance, sometimes not; sometimes keeping house and sleeping with one or another man in exchange for his keeping her in booze; forever bouncing in and out of rooming houses, live-in jobs, hospitals, alcohol programs, halfway houses, and on and on, always drinking, always Valium. Betty soon discovers that wherever she is, even in the hospital, someone has bugged her room or telephone. In the late 1970s, she tells a psychiatrist some of her life story and he has her placed in a schizophrenic ward in the state mental hospital where she remained for 33 days. “I’ll never forgive him for doing that to me, OK? Especially after me confiding in him.”

Betty then goes through two separate alcohol treatment cycles from the state hospital to a farm for homeless alcoholics. On October 31, 1979, at The Farm, something takes hold—prayer, she believes—and Betty stops drinking. She gets live-in jobs caring for sick or elderly persons, sometimes on her own, sometimes through Operation Match, and alternates working with public assistance. In 1983, on a job, Betty re-injures her back, loses a job as a nurse’s aide in a nursing home, spends several months at two D.C. shelters, and after a real or imagined (she herself is uncertain) threat of attack from three men on the street, she leaves D.C. and goes to the Crisis Center where staff persons tell her about The Refuge.

Beverly

Beverly is 23 years old. She is blonde and blue-eyed and has a slight lisp. Everyone says she is very pretty, and Betty makes a standing joke of her offer to be Beverly’s “madam” and split the proceeds.

Beverly is the youngest of three children; her sister is 24, and her brother is 26. Both her parents—now in their mid-40s—worked for Safeway. Her father and mother had terrible fights, sometimes breaking the furniture, and Beverly remembers her mother grabbing the children and running to a neighbor’s house for protection. Her father also abused her sister and brother but never Beverly because she had been sick from birth (“My esophagus didn’t close—it stayed open all the time”) and was overly protected. Her father had himself been an abused child. His own father had been a wino in downtown D.C. and was now in a nursing home. Beverly’s father visits him occasionally, but Beverly has never met him.

Beverly remembers that both her parents had undergone electric shock treatments. Sometimes Beverly’s mother would run away for days at a time, but her father always took her back. As small children, Beverly and her brother and sister were forced to attend a Catholic church every Sunday and to go to Sunday School.

Beverly’s father moved out when she was six. He lived nearby and the children saw a great deal of him. In the house, the fighting continued as Beverly’s brother “took over where my dad left off.” The family drew up sides. “My sister is addicted to my mother. My mother can do no wrong. She doesn’t like my father and I don’t like my mother.”

As a child and young girl, Beverly was shy and quiet. At school, she had no friends and was teased mercilessly about her severe speech problem. Nobody wanted to hear her talk so she never got to finish her sentences. Later she learned “to say everything quick before they had a chance to interrupt me. I taught myself that.” People said she had a learning disability but she thinks she was just a very slow learner. For the sixth grade, she was sent to a special school for learning-disabled children. At that time, too, her brother moved out to live with their father. Her brother’s only ambition was to get stoned (on drugs) and stay stoned. He was also in trouble with the police. Her sister, she said, “turned out to be the biggest slut in town.” Beverly herself never did drugs. “I’m a Goody Two-shoes,” she said, who always got along better with older people than with her peers.

When Beverly was 15, her mother remarried. Her stepfather had been a neighbor and longtime family friend, one of Beverly’s favorite people. But as soon as he became their stepfather, “he became a jerk and treated us terrible. He was irritable and snotty. He wouldn’t eat with us. He ate his meals in his bedroom.… His door was always closed.” Meanwhile, her father had also remarried.

Beverly lost her first real boyfriend to her own best girlfriend when she refused to have sex with him before marriage. She swore that would never happen again. In her last year at high school, she began dating the boy next door, and three months later she was pregnant. Five months pregnant, defying everyone, she went to her graduation ceremonies and received her diploma.

When Beverly came home with the baby, her mother took over. “Come to Mommy,” she would say to the baby, dismissing Beverly’s protests with a wave of her hand. Almost immediately, Beverly’s mother and stepfather “became addicted to the baby. They were terrified of losing him. They made me so dependent on them I was more like a prisoner there.… My mom and I fought all the time.” When Beverly was 19 and the baby a year and a half, Beverly’s mother learned that she had secretly applied for public assistance and was planning to take her baby and live on her own. Soon thereafter, the police came to the door. “We have a petition here that says you need psychiatric care,” they told Beverly, and she was taken to the hospital in handcuffs. Her mother had told the authorities Beverly was a danger to herself and others, and a neighbor said that Beverly was suicidal because she had heard her tell her father, after breaking up with her fiancé, “I get so frustrated at times, I wish I was dead.”

Beverly was released from the hospital the same day, July 17, 1982. She left the baby with a friend while she hunted for a place to live. That was the last time she ever saw her son. Two days later, when she returned to pick him up, she was told, “He’s not here. Your mom came last night and took him.” Lawyers told Beverly to take her mother to court and she would surely win, but Beverly never had the money to do it. Legal Aid told her to “come back when you get your life straightened out.”

Beverly moved in with a friend and spent her days looking at pictures of her son, her nights crying. After four months, she moved in with her father, who had separated from his second wife and was living in a small apartment. In June 1984, Beverly met and started dating a security guard. Three months later they were married in Ocean City and lived there a couple of months before returning to the D.C. area to live with his parents. Her husband took a job as a construction laborer.

Four months into the marriage, the fighting got so bad that Beverly left the house and checked herself into County General Hospital. A week later, when she was about to be discharged, her husband told her he “could not stay married to a crazy person. I’m leaving.”

Out of the hospital, Beverly again moved in with a friend while she attended a day program at the hospital. Again she tried to live on her own when she got a stock clerk job at K mart, but she found the job too stressful and again went to live with her father, who had taken a larger apartment to accommodate her. After a terrible fight with him, she tried to kill herself by overdosing on some of his medications. She was released from the hospital as soon as she was out of danger.

In July 1985, she started dating a friend of a friend and soon moved in with him. He was 40 and a drunk, and his 17-year-old son lived with them. Beverly did not get along with the son, couldn’t stand the drinking, and several times moved out to stay with another friend. Finally, last fall, she moved out for good and stayed with a friend in Section 8 housing. The rules required that Beverly leave after two weeks. She went to the Crisis Center. The Crisis Center sent her to Social Services. Social Services told her about The Refuge.

Carlotta

Carlotta is a small and dark Latina woman with long, straight black hair. She speaks with a heavy Spanish accent.

Carlotta was born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1951. She was the third of four children, each a year apart from the next. Her father was an encyclopedia salesman, or maybe a supervisor of encyclopedia salesmen. He worked very hard and the family lived moderately well until Carlotta was 10 years old, when the father moved out of the family apartment. The mother went to work as a teacher in a local school, but the pay was low and the now fatherless family was very poor. “Life was very hard for us because a family should have a father and a mother.”

Carlotta was an average student. Her two older sisters were her best friends throughout her childhood. She...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Day by Day

- Work and Jobs

- Family

- The Servers and the Served

- Making It Body and Soul

- My Friends My God Myself

- Making It Together

- Some Thoughts on Homelessness

- Appendixes

- APPENDIX A Where Are They Now

- APPENDIX B Life Histories

- APPENDIX C How Many Homeless

- APPENDIX D Social Service Programs

- APPENDIX E Research Methods and Writing

- Index