![]()

Positioning: Creating Value

If a man … make a better mousetrap than his neighbor, tho’ he build his house in the woods, the world will make a beaten path to his door.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lectures

The last chapter explained that commitment-intensive or strategic choices are choices among significantly different bundles of durable, specialized, untraded factors, and that they resist yet nevertheless require in-depth analysis. It is useful to begin such analysis by thinking through the position (i.e., strengths and weaknesses) each strategic option implies with respect to product market competitors. Emerson explained why more than a century ago. Suppose you are deciding whether to try to develop a new type of mousetrap. The first thing to look at is how the innovation will stack up against competing mousetraps. If the innovation is no better than them, it is unlikely to generate much value. If it does offer some sort of advantage, however, it is worth further thought.

This chapter describes the framework that has been developed in the last few decades for analyzing the positions implied by strategic options. In order to avoid having to tackle the complexities of commitment all at once, it invokes two assumptions that conveniently restrict, in the customary way, the scope of positioning analysis. The first simplifying assumption is that the value to the organization’s owners of the pursuit of one commitment option as opposed to another is independent of the differential reactions of competitors, buyers, suppliers, employees and other interested parties. The second one is that the organization will persist with the course of action favored by the option it initially elects to pursue. Because of these assumptions, positioning analysis is substantively incomplete.

Fortunately, the restrictive assumptions implicit in positioning analysis, of zero differential reactions and zero revisions, can be relaxed. Chapter 5, on sustainability analysis, dispenses with the assumption of zero differential reactions and thereby adds a game-theoretic dimension to the decision-theoretic outlook characteristic of much of the work on positioning.1 Chapter 6, on flexibility analysis, dispenses with the second restrictive assumption, of zero revisions. This generalization requires a full-blooded treatment of uncertainty and its interaction with irreversibility, informed by recent insights from informational economics.

Taken together, chapters 4 through 6 outline a coherent way of comparing the aggregate values of strategic options by overlaying considerations of sustainability and flexibility on option-by-option estimates of positioning value. This chapter is simply meant to help us get to a first-cut evaluation of such options, under restrictive yet convenient assumptions that can later be relaxed. Its conceptual fare is sandwiched between two examples. The first example, which follows immediately, should hint at the power of positioning analysis, in spite of its restrictive assumptions, to sharpen strategic choice. The second example, toward the end of the chapter, is meant as a review.

RECONSIDER THE LAUNCH OF THE LOCKHEED TRISTAR.

The best way to illustrate what positioning analysis can do for you is to apply it to a strategic choice of a sort that is widely supposed to defy careful analysis: the launch of a large new passenger jet. Newhouse (1982, p. 3) has nicely evoked the atmosphere of such choices:

In deciding to build a new airliner, a manufacturer is literally betting the company, because the size of the investment may exceed the company’s entire net worth. The remarkable scale on which they operate induces a curiously understated, rather casual style among senior executives in this industry. Betting the company, for example, is being “sporty.”

Lockheed was being rather sporty, in spring 1968, when it bet nearly three times its net worth on a three-engine wide-body jet later named the TriStar. Since the failure of its last big commerical launch, the Electra, in 1955, Lockheed had become almost entirely dependent on military sales, a condition that its top management wanted to rectify. In late 1966, when it lost the government-run competition to build the U.S. supersonic transport (SST), its chairman, Daniel Haughton, reacted by putting the SST designers to work on the wide-body.

Wide-bodies, with two passenger aisles rather than one, were made possible by the “high-bypass (power)” jet engines developed for the C-5A military transport, a project on which Lockheed was the prime airframe contractor. Boeing’s 747, discussed in chapter 2, represented the first attempt to commercialize high-bypass jet engines: it used four of them. But the 747 seemed, like the 707 which had pioneered narrow-body jet technology ten years earlier, to leave a hole in the market for smaller planes powered by the same engine. There were two smaller alternatives to the four-engine 747: a three-engine design optimized for about three-quarters of its capacity, and a two-engine design optimized for about one-half. Lockheed picked the trijet rather than the twin-jet, and was quickly followed into the same market segment by McDonnell Douglas’ DC-10.

By spring 1968, the pattern of early orders plus the precommitment of McDonnell Douglas to the market for large commercial aircraft had made it clear that if Lockheed pushed ahead with the TriStar, it would have to split the market with the DC-10. At this juncture, Lockheed had committed only 1% to 2% of the billion-plus dollars thought to be required for the development of the TriStar. It went ahead anyway, without ever really questioning the commercial viability of a position as a trijet duopolist rather than monopolist. By its own account, it eventually lost about $2.5 billion on the TriStar program—an average of $10 million on each plane sold until the program was terminated in 1983. More careful analysis of the costs and benefits of achieving a duopoly position in trijets might have averted these losses by suggesting that the TriStar could not possibly pay for itself off a split market.

To see how more careful analysis might have helped Lockheed, it is necessary to review the analysis that it actually undertook. According to the information I have been able to piece together, Lockheed anticipated that the total nonrecurring outlays on developing and tooling up for the TriStar would be on the order of $1 billion, and that recurring production costs would be subject to a 77% learning curve, approximating $15.5 million for the 150th TriStar and $12 million for the 300th. Based on these estimates and a price forecast of $15.5 million per plane, the (undiscounted) cumulated cash flow from the TriStar program would turn positive in the vicinity of 300 planes—a sales target Lockheed was confident of surpassing when it made its announcement.

When McDonnell Douglas announced the directly competitive DC-10 three months later, Lockheed’s top managers asked themselves whether they could still sell 300 TriStars—the number had been detached from the context in which it had been derived—and came up affirmative, largely because of a sense that their plane was technically superior. Lockheed went ahead with the TriStar and was saved from bankruptcy only by the grace of the U.S. government. Where, in analytical terms, did it go astray?

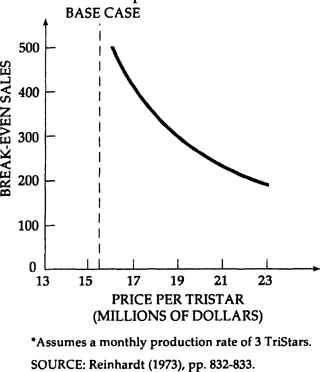

Most obviously, Lockheed’s analysis failed to account for its cost of capital and thereby seriously underestimated the TriStar’s true break-even point. The assumption of a zero cost of capital in break-even calculations, while customary in the aircraft industry, had become dysfunctional by the time the development costs for a new plane exploded into ten figures. In 1968, high-grade, long-term corporate bonds were yielding 8% or 9%, suggesting the application of at least a 10% discount rate to the cash flows expected from the TriStar program and implying a serious threat of bankruptcy in the event of program failure. Reinhardt (1973) has calculated that at a 10% discount rate, Lockheed would have lost nearly $250 million, in present value terms, if it sold 300 planes (the undiscounted “break-even”) at the price and pace it had originally forecast. The true break-even point under those assumptions appears to have been slightly over 500 planes. Raising the discount rate to 15% would have raised the break-even point to over 1,000 planes. Accounting for its cost of capital should therefore have suggested to Lockheed that even if its (optimistic) forecasts for trijet demand were fulfilled, the TriStar would have to capture nearly two-thirds of that market, rather than a bit more than a third, to pay for itself.

Could Lockheed’s trijet decisively beat McDonnell Douglas’? Lockheed seems to have assumed that the superior design of the TriStar (and its Rolls-Royce engines) would assure its competitive success. It seems, for that reason, to have taken a very narrow view of benefits to buyers. The TriStar did have some appealing characteristics (in such respects as hydraulics, cockpit layout and the mount for the tail-engine) relative to the DC-10, but it had become clear by spring 1968 that the airlines would not pay more for one plane than for the other. Any residual design-related disadvantage for the DC-10 was more than offset by its various advantages. The reputation of McDonnell Douglas enabled the DC-10 to secure the two largest domestic carriers, United and American, as its launch customers: they had had doubts about Lockheed since the Electra debacle and simply didn’t trust its British engine supplier, Rolls-Royce (which had, up to that point, been shut out of the U.S. market). They regarded McDonnell Douglas, in contrast, as the one supplier that might give Boeing a run for its money and therefore, other things being reasonably equal, the one to favor. Without United and American, there would have been no DC-10; with their orders in hand, McDonnell Douglas arguably entered the next phase of the competition stronger, not weaker, than Lockheed.

The DC-10 also managed to achieve a timing advantage over the TriStar, for reasons including its more evolutionary design and McDonnell Douglas’ prior experience with large passenger jets. The potential for such an advantage was evident in the late 1960s, even before Lockheed ran into unanticipated problems with its engine supplier and its military contracts. While Lockheed was planning to work on just one version of the TriStar in the first few years of its trijet program, McDonnell Douglas was planning to develop, over roughly the same time frame, two versions of the DC-10: one that would compete head-on with the TriStar, and an extended-range version that would compete, somewhat less directly, with the 747. If both development efforts achieved technical success—and they did—the DC-10 would have a head start at winning the rest of the race. For these reasons, it wasn’t at all clear, in spring 1968, that the TriStar’s superior design would allow it to outsell the DC-10, i.e., (perhaps) achieve a positive net present value.

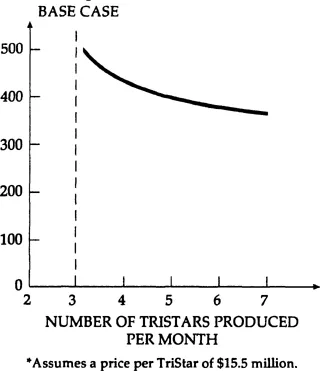

By implication, the sales volume required to make the TriStar pay for itself seemed, on the basis of Lockheed’s original projections about unit margins (discounted at 10%), unlikely to be achieved. To make matters worse, the original margin projections should themselves have been revised downward to reflect competition from the DC-10. Competition had already forced Lockheed to cut the price of the TriStar from $15.5 million to $14.2 million. By limiting production rates and making them fluctuate, it would also raise the average level of costs. Reinhardt’s (1973) analysis demonstrates that each of these margin-reducing effects could have been forecast to have a very adverse effect on the economics of the TriStar program (see Exhibits 4.1a and 4.1b). It leads him (p. 834, emphasis in original) to the conclusion that “One may doubt that there existed in 1968 a feasible price-sales combination for the Tristar at which the program could have been expected to generate a positive net present value.”

Exhibit 4.1a Impact of Price*

Exhibit 4.1b Impact of Production Rates*

Thus, while one can understand the desire of Lockheed’s top management to reenter the commercial market, it was a poor idea to do so with a plane that could have been foreseen to lose the company a lot of money at a time when it was already overstretched. Further, even if Lockheed was determined to reenter the commercial market in time for the next reequipment cycle, the launch of the DC-10 should, at the very least, have forced it to reassess whether all of the twin-jet market wouldn’t be better than half or less of the trijet market. Note that the European Airbus consortium later seized on the twin-jet concept and did rather well with it.

The Lockheed story illustrates the potential of positioning analysis. It also hints at some general guidelines for evaluating the competitive positions implied by different strategic options. These are systematized in the next section.

POSITIONING ANALYSIS COMPARES THE COSTS INCURRED AND THE BENEFITS DELIVERED BY STRATEGIC OPTIONS.

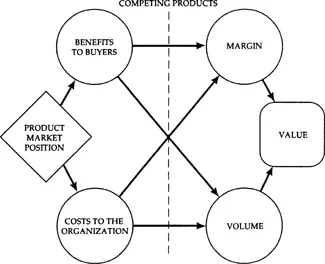

The modern framework for the positioning analysis of strategic choices is outlined in Exhibit 4.2. The framework’s logic is straightforward. It starts with the observation that strategic choices, while hitherto viewed (in this book) from the perspective of factor deployments, have predictable implications for the level of costs incurred by the organization and the level of benefits delivered by its product(s) or service(s) to buyers. Buyers’ trade-offs among competing products determine the margin-volume combinations available to the organization from each strategic option. The positioning value of an option is defined in terms of the most advantageous margin-volume combination it is expected to permit, i.e., in terms of the margin per unit times the number of units sold. Sometimes, as in the case of the TriStar, it is essential to trace out the margin-volume combinations over time instead of relying on timeless snapshots of them. Each of these elements of the received framework for positioning analysis deserves to be discussed in more detail.

Exhibit 4.2 The Framework for Positioning Analysis

The Product Market Perspective

The epigraph from Emerson hinted at the advantages of tracing the implications of commitment-intensive or strategic choices all the way through to the level at which organizations finally market their products (or services). Analysis at this level, henceforth the product market level, should be thought of as spanning all the functions that the organization performs en route to earning its daily bread. For instance, analysis at the product market level of whether to try to build a better mousetrap (or the TriStar) would pull together the implications for R&D, production and marketing instead of focusing on just one of those functions.

Adoption of the product market perspective is more than just a matter of taste or tradition. Recall, from chapter 3, that much of the difficulty of analyzing strategic choices stems from the extreme imperfections of markets for durable, specialized, generally untraded factors. These imperfections complicate direct assessments of the values of such factors. It is useful, for that reason, to exploit the long-run duality between the factor market and product market perspectives on the organization by evaluating the distinct bundles of factors implied by different options from the product market side. Lockheed, for instance, did not analyze the expenditure of a billion-plus dollars on developing the TriStar by trying to figure out what the factors thereby created might be sold for. Instead, it tried to figure out whether it could sell enough TriStars at a price that would allow it to cover the program’s total costs.

The product market perspective obviously implies cross-functional analysis of strategic choices. Cross-functional analysis is essential because of evidence that product market competitors may be able to do equally well (or poorly) in different ways. For instance, Hunt’s (1972) seminal study of major home appliances (refrigerators, stoves, dishwashers, washers and dryers) in the United States uncovered viable narrow- as well as broad-line positions in that industry: Maytag had historically outperformed the industry averages with the former, and General Electric with the latter. Since it does seem to be possible for product market competitors to succeed with quite different combinations of functional strengths and weaknesses, the implications of strategic choice for competitive position must be understood at a cross-functional level. Lockheed apparently forgot this point: it apparently overemphasized the TriStar’s design and underemphasized considerations related to manufacturing, marketing and finance.

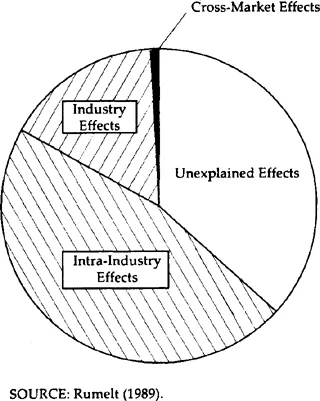

The product market perspective also implies that even when a strategic choice impinges on more than one product market served by the organization, its effects should be spelled out at the level of individual product markets.Exhibit 4.3, for instance—that cross-market influences on organizational performance are, on average, an order or two of magnitude weaker than influences attributable to competitive positions in individual markets (which include both intra-industry effects and industry-level effects). To emphasize cross-market considerations at the expense of careful market-level analysis anyway is to court disaster. In launching and persisting with the TriStar, for instance, Lockheed gave too much weight to its desire to re-balance its portfolio of businesses and too little to careful analysis of the trijet market. In deference to such disasters, modern positioning theory stipulates that strategic choices should always be analyzed in terms of their implications for competitive positions in individual product markets.

Exhibit 4.3 Sources of Variance in Business Unit Profitability

Agreement on a product m...