This is a test

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Japanese Woman

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Westerners and Japanese men have a vivid mental image of Japanese women as dependent, deferential, and devoted to their families--anything but ambitious. In fact, the author shows, Japanese women hold equal and sometimes even more powerful positions than men in many spheres.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Japanese Woman by Sumiko Iwao in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

WORK AS OPTION

At a time when women all over the world are entering the workplace, taking their places beside men or even replacing them, many wonder whether Japanese women today remain tied to the home, subservient to husbands and children. Statistics indicate that this is far from the case. Women make up 38 percent of the total employed labor force (as of 1991), and this does not include the self-employed and farmers. Actually, a considerable proportion of Japanese women have worked for a long time; what has changed, and quite drastically, is which women work and why. Also, the types of work they do have greatly diversified, and the way they go about work has changed. Less a means of survival, work for the vast majority of women is now an option, a means by which they can gain and enjoy freedom and economic autonomy. At the same time, they have become virtually indispensable to the Japanese labor market, which suffers from a shortage of labor, although it must be said that workplaces are still overwhelmingly staffed by men.

TRADITIONAL ROLES AND WORK

We can gain a more accurate perception of the contemporary situation by first looking briefly at the role and conditions of working women in the past. A surprisingly large number of women have worked in nondomestic jobs since the beginning of the modern period (late 19th century). In prewar times (1920s and 1930s), it was quite common for women to be engaged in farm work, sales, domestic service, factory work (such as weaving), and cottage industries (e.g., sewing, embroidery, toy assembly).

Whatever type of work married women did, however, it was of a kind that could be done even while keeping an eye on children and attending to regular household tasks. It was also work done out of necessity. Both single and married women worked not only to improve their own lives but also (and more importantly) to make things better for their families. In prewar periods of famine, very poor farming families were often forced to sell their daughters into prostitution (the number of cases increased sharply around 1934). The prettier ones might be snapped up by the geisha houses, but the less lucky ended up in ordinary brothels. Most Japanese were very poor before World War II, incredibly so by today’s standards, and the only alternative to indigence was hard work. As a farming people accustomed to the unpredictable and sometimes destructive forces of nature, Japanese accepted their hardship as fate, comforting themselves with the refrain “It cannot be helped [shikata ga nai].” Perseverance and obedience became virtues along with diligence and self-sacrifice.

The passivity and diligence that characterized Japanese before World War II have not changed much even today, but life has become much easier for both men and women as a result of economic growth and the affluence that made possible technological advancement both in the home and the workplace. Today, Japan has become sufficiently affluent that the number of women who have to work out of absolute economic necessity has dwindled. A totally new type of woman is joining the labor force: those who do not have to earn money to support their families but who choose to work for other reasons. The fact that they no longer work only for economic survival has been a factor in the slowly rising status of working women.

After World War II, and until 1965, the proportion of working women in the total female population was one of the highest among developed nations throughout the world owing to the large farming population. But while in other countries women joined the labor force in growing numbers, in Japan the trend was actually in the other direction, with fewer women working as economic growth gained momentum and the farming population entered the cities, where men became salaried workers and women became full-time housewives.

Japan reconstructed its virtually annihilated economy during the 1940s and 1950s and rode smoothly on the wave of economic growth with an approximately 10 percent annual growth rate during the 1960s and up to the mid-1970s. While men devoted themselves to the expansion of the gross national product, women enjoyed the fruits of economic growth, many becoming nonworking housewives. Then, in 1975, the trend again reversed, and the increase in the number of women in the work force continues today. As the economy developed and society grew affluent, women who had seen themselves only in terms of their family’s and their children’s goals began to ask themselves, “What do I want out of life?” And they have begun to seek concrete answers to that question. One answer has been to work and earn an income to spend as they wish.

THE FEMALE WORK FORCE IN THE 1960S AND 1970s

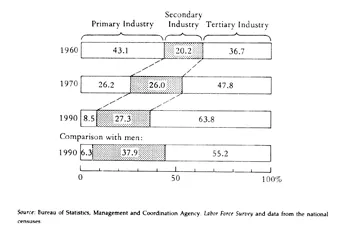

Industrialization and urbanization in the 1960s and 1970s set the stage for the first transformation in the female work force. In 1960 the largest percentage (43 percent) of working women were employed in the primary sector, mainly agriculture; 20 percent, in secondary industry (manufacturing); and nearly 37 percent, in the tertiary sector (schools and offices). Those employed in the secondary sector were mostly young junior high school graduates (having completed compulsory education) who worked in factories, large and small.

In the tertiary sector, women worked as teachers (53 percent of working women who were college graduates worked as teachers in 1965) and in clerical positions (21 percent of female college graduates who were working in 1965 were “OLs” or “office ladies”). Full-time employed women with high school or college diplomas were called “sararī gāru [salary girls]” or “BGs” (business girls). As suggested by the use of the word girl, these women were almost all single and young, and they uniformly quit their jobs upon marriage. Some companies routinely set the retirement age for women separate from that for men, sometimes as early as age 35. It was not surprising that women were known as the “flowers of the office [shokuba no hana]”—pretty to look at and decorative but insubstantial and transient.

Duration of continuous service is a particularly important factor in the lifelong employment systems of large corporations in Japan. In order to achieve high status in a large organization in the business sector, women have to stay on the job long enough to compete with men for promotion (at least until employment practices shift toward greater job mobility in Japan). Men find it hard enough to gain promotion in the first four years after joining a company, but for women, the vast majority of whom stay employed for only four years, the hurdles are even greater. Recent surveys show, in fact, that it takes some 20 years for the average woman in the business sector to be promoted to a managerial post.1

Social images of work outside the home discouraged women from pursuing careers or long-term employment. Working was considered to be secondary since a woman’s place was “naturally” in the home. Marriage was known as “eikyū shūshoku [lifetime employment]” and considered to offer the greatest possible security and fulfillment for a woman. Jobs outside the home were referred to as koshikake (temporary seat) and were valued primarily as a chance for a woman to observe and learn about the world outside the home (shakai kengaku) while not incurring a long-term job commitment.

In the world of business, women were temporary pinch hitters, or supporters, not regular players in the game. In terms of salary, promotions, and type of work assigned, the worlds of men and women in the corporation were clearly and distinctly separate. Women seemed to affirm (and many still do affirm) the separation, considering themselves to be short-term, noncareer workers who therefore do not need to take equal responsibility with male employees. Their lower wages and the less responsible tasks they were expected to perform did not (and still do not) generate tension in the workplace. They contented themselves with simple clerical tasks and services for their male supervisors (such as answering telephones, serving tea, and emptying ash trays). Essentially, they were performing the housekeeping chores of the office, applying traditional womanly skills.

In the early 1960s the Japanese economy began to shift toward the service sector—finance, information, commerce—a development signaling the advent of the postindustrial age, and the number of women working in the tertiary sector increased along with that of men. By 1970 those in the primary sector decreased sharply (to 26 percent from 43 percent in 1960, see Fig. 6-1). Women in the secondary sector increased slightly, with the tertiary sector accounting for the majority (at 48 percent of all working women).

Although it is seldom noted or acknowledged, working women can claim, through their contribution to the work force, at least one third of the credit for Japan’s miraculous economic growth—and perhaps even more since they also provided home environments that supported and sustained the overworked, embattled men caught up in the cogs of Japan, Inc. (as the political/industrial complex of postwar Japan is often described). There is no question that Japanese industry surged ahead in the postwar period partly because the role of women was such that it allowed men to put work above everything else. Yet women are all but invisible as far as anyone outside Japan can see; men seem to be the only moving forces in the country’s history, society, and economic growth.

Figure 6-1 Industry Distribution of Women Workers (in percent)

By 1965, reflecting the zeal and respect for education in Japan, nearly 70 percent of the women who completed junior high school (compulsory education) went on to senior high school. The concomitant decrease in the number of nimble-fingered young women entering the work force for whom manual labor was the only option forced the secondary sector to look elsewhere to fill its demands. The economy was growing rapidly, and the labor shortage in the secondary sector was acute.

Industry’s needs were partly fulfilled by part-time workers (persons working 35 hours or less per week by choice, a classification borrowed from American management practice), mostly housewives under the age of 35 with children of primary school age or older and with time to work outside the home. However, day care, for the entire day or for after-school hours, had yet to become widespread, and many of the children of these women had to fend for themselves, letting themselves into their homes after school and waiting until their mothers returned in the evening. The problems of “latchkey children” became a key social issue and the concern of many adults starting around 1965. Some factories, determined to attract and keep cheap female labor (primarily part-time blue-collar workers with small children), started up on-site day care facilities. The general trend was for mothers with infants and small children to remain at home, however, so the number of working mothers did not substantially increase. In the 1960s part-time female workers came mostly from lower-income families and were primarily engaged in blue-collar jobs; socially, therefore, they continued to be looked down upon.

There were other notable changes among working women during the decade of the 1960s. The percentage of single women among those who worked as a whole decreased drastically and that of married women increased, to 51 percent by 1970 (from 38 percent in 1960). The expanding economy produced considerable demand for female part-time labor, and by 1970 the number had increased to 12 percent of employed women (from 9 percent in 1960). Nevertheless, mothers with infants and small children working outside the home in full-time, white-collar jobs were still a rarity, except in the professional careers in which women have long played an important role, such as nursing and teaching. One reason was that domestic help was rapidly becoming a luxury, partly due to high wages and partly to the greater attractions of regular office or factory work over live-in domestic service. In addition, as a result of urbanization, nuclear families had proliferated and grandparents who could take care of children were not available.

Another reason inhibiting women from joining the work force were the beliefs, widespread in the sixties, that improper maternal care was the cause of juvenile delinquency among children and that children of working mothers were quick to get into trouble.2 This myth was exploited in the media and served for a long time to discourage many mothers from seeking outside employment. Even today, when a child becomes delinquent, it is the mother who takes the brunt of the blame, not only from society and the schools but from the father, who is not expected to play a role in molding the behavior of his children. Working mothers, nevertheless, gradually multiplied.3

Although the number of working women increased, their lives remained hemmed in by many discriminatory practices and customs. For a long time women did not make a big issue of such practices, working around them and despite them. While American society was going through a traumatic women’s liberation movement, Japanese women as a whole had yet to voice their complaints publicly or seek legal redress for the disadvantages they suffered.

It was not until the United Nations Decade for Women that the issue of equal opportunity and status for women came to the fore. Existing laws for working women tended to be protective rather than concerned with equality, as evidenced by the Labor Standards Law (discussed later in this chapter).

WORKING WOMEN TODAY

Several characteristics of the Japanese workplace affect the circumstances of working women. First, nearly 90 percent of companies are either small- or medium-sized enterprises with less than 300 workers; these companies employ over 80 percent of working women and 70 percent of men. Many women, especially part-timers, are absorbed by this stratum of industry. Second, compared to that in the United States, there is less job mobility in the Japanese job market, especially in the case of the larger corporations. Third, promotion and accompanying pay raises are connected more closely to seniority than to achievement. The latter two characteristics make the hope for equal treatment unrealistic for women who want to (and have to) stay at home while their children are small and return to work when the children are older. Therefore, women are eager to obtain qualifications (or certification) of some sort on the basis of which they can break through the barriers of seniority.

By 1985, reflecting structural changes in the Japanese economy, the proportion of women working in the tertiary sector further increased, leaving only a small portion in the primary sector. In the 15 years between 1970 and 1985 the number of employed women increased by 50 percent, totaling nearly 15.5 million. By 1990 the largest number of women workers were in clerical positions, with the next largest category being that of crafts and production process workers; together, these represent the profession of more than half of all working women (see Table 6-1). Figures show that the number of women working in traditional occupations such as nursing, typing, nutrition, telephone operating, and garment making have decreased, while those venturing into the jobs previously monopolized by men—such as medicine, law, and the civil service, as well as the newer occupations like engineering, marketing, merchandising, sports instruction, journalism, and business consulting—are increasing. Highly motivated and capable women looking for equal employment opportunities are especially attracted to the latter, newer, occupations, where men have not necessarily been dominant. According to International Labor Organization statistics, 46 percent of women workers in Japan were employed in professional and technical jobs (the majority of these are in teaching and nursing).4 This figure for Japanese women was not much lower than the 48 percent for American women and the 55 percent for Swedish women. However, about 10 percent more Japanese women were engaged in factory work than elsewhere and only 6 percent of managerial jobs were held by women, as compared with 34 percent in the United States and 21 percent in Sweden.

With more women continuing to work even after they marry, the females in offices today in Japan are no longer insubstantial, transient “flowers.” The percentage of women who work for the same company for 10 years or more has increased over the past 10 years from 9 percent in 1980 to 26 percent in 1990. The average age of working women in 1990 was 36 years, ten years older than the average for 1960. Married women make up the bulk of working women, and the percentage of part-time workers rose to 28 percent (as of 1990) of all employed women. Many of these women are returnees...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- CONTENTS

- MYTHS AND REALITIES

- THE STORY OF AKIKO

- MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

- COMMUNICATION AND CRISIS

- MOTHERHOOD AND THE HOME

- WORK AS OPTION

- WORK AS PROFESSION

- POLITICS AND NO POWER

- FULFILLMENT THROUGH ACTIVISM

- DIRECTIONS OF CHANGE

- NOTES

- INDEX