eBook - ePub

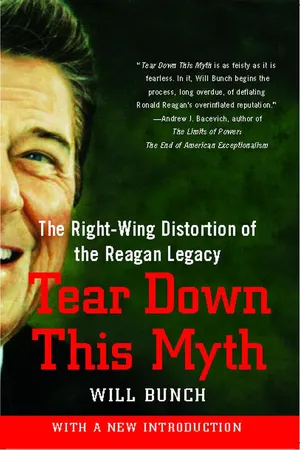

Tear Down This Myth

How the Reagan Legacy Has Distorted Our Politics and Haunts Our Future

This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tear Down This Myth

How the Reagan Legacy Has Distorted Our Politics and Haunts Our Future

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this provocative new book, award-winning political journalist Will Bunch unravels the story of how a right-wing cabal hijacked the mixed legacy of Ronald Reagan, a personally popular but hugely divisive 1980s president, and turned him into a bronze icon to revive their fading ideology. They succeeded to the point where all the GOP candidates for president in 2008 scurried to claim his mantle, no matter how preposterous the fit. With clear eyes and an ever-present wit, Bunch reveals the truth about the Ronald Reagan legacy, including the following:

- Despite the idolatry of the last fifteen years, Reagan's average popularity as president was only, well, average, lower than that of a half-dozen modern presidents. More important, while he was in office, a majority of Americans opposed most of his policies and by 1988 felt strongly that the nation was on the wrong track. Reagan's 1981 tax cut, weighted heavily toward the rich, did not cause the economic recovery of the 1980s. It was fueled instead by dropping oil prices, the normal business cycle, and the tight fiscal policies of the chairman of the Federal Reserve appointed by Jimmy Carter. Reagan's tax cut did, however, help usher in the deregulated modern era of CEO and Wall Street greed.

- Most historians agree that Reagan's waste-ridden military buildup didn't actually "win the Cold War." And Reagan mythmakers ignore his real contributions -- his willingness to talk to his Soviet adversaries, his genuine desire to eliminate nuclear weapons, and the surprising role of a "liberal" Hollywood-produced TV movie.

- George H. W. Bush's and Bill Clinton's rolling back of Reaganomics during the 1990s spurred a decade of peace and prosperity as well as the reactionary campaign to pump up the myth of Ronald Reagan and restore right-wing hegemony over Washington. This effort has led to war, bankrupt energy policies, and coming generations of debt.

- With masterful insight, Bunch exposes this dangerous effort to reshape America's future by rewriting its past. As the Obama administration charts its course, he argues, it should do so unencumbered by the dead weight of misplaced and unearned reverence.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Tear Down This Myth by Will Bunch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Parties. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

RONALD REAGAN BOULEVARD

“Who controls the past” ran the Party slogan, “controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.”

—George Orwell, 1984

The present was January 30, 2008, when four powerful men walked onto a freshly built debate stage in Simi Valley, California, seeking to control the past—most ironically, the American past that was at its peak in that very “Morning in America” year of 1984. They knew that whoever controlled the past on this night would have a real shot at controlling the future of the United States of America.

Lest there be any doubt of that, the large block letters UNITED STATES OF AMERICA hovered for ninety minutes over the heads of these men—the last four Republican candidates for president in 2008—who had made the pilgrimage to the cavernous main hall inside Simi Valley’s Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. This was the final debate of a primary campaign that had basically started in this very room nine months ago and now was about to essentially end here—in what was becoming a kind of National Cathedral to Ronald Reagan, even complete with his burial vault. The block letters were stenciled across the hulking blue and white frame of a modified Boeing 707 jetliner that officially carried the bland bureaucratic title of SAM (Special Air Mission) 27000, but bore the title of Air Force One from 1972 through 1990—a remarkable era of highs and lows for the American presidency.

To many baby boomers, this jet’s place in history was burnished on August 9, 1974, when it carried the disgraced Richard Nixon home to California on his first day as a private citizen. But that was before SAM 27000 was passed down to Ronald Reagan and now to the Ronald Reagan legacy factory, which flew it back here to the Golden State, power-washed it clean, and reassembled it as the visual centerpiece of Reagan’s presidential library. It was now part American aviation icon and part political reliquary, suspended all deus ex machina from the roof in its new final resting place, with Reagan’s notepads and even his beloved jelly beans as its holy artifacts.

And for much of this winter night, the men seeking to become GOP nominee—and hopefully win the presidency, as the Republican candidate had done in seven out of the ten previous presidential elections—looked and felt like tiny profiles on a sprawling American tarmac under the shadow of the jetliner, and of Reagan himself. Fittingly, each chose his words carefully, as if he were running not to replace the hugely unpopular George W. Bush in the Oval Office—at an inauguration 356 days hence—but to become the spiritual heir to 1980s icon Reagan himself, as if the winner would be whisked up a boarding staircase and into the cabin of SAM 27000 at the end of the night and be flown from here to a conservative eternity.

As was so often the case, news people were equal co-conspirators with the politicians in creating a political allegory around Reagan. The debate producer was CNN’s David Bohrman, who’d once staged a TV show atop Mount Everest and now said the Air Force One backdrop was “my crazy idea” and that he had lobbied officials at the library to make it happen. He told the local Ventura County Star that the candidates were “here to get the keys to that plane.”

By picking Reagan’s Air Force One and the artifacts of his life as props for a Republican presidential debate that would be watched by an estimated 4 million Americans, CNN shunned what would have been a more obvious motif: the news of 2008. If you had been watching CNN or MSNBC or Fox or the other ever-throbbing arteries of America’s 24-hour news world, or sat tethered to the ever-bouncing electrons of political cyberspace in the hours leading up to the debate, you’d have seen a vivid snapshot of a world superpower seeking a new leader in the throes of overlapping crises—economic, military, and in overall U.S. confidence.

On this Wednesday in January, the drumbeat of bad news from America’s nearly five-year-old war in Iraq—fairly muted for a few weeks—resumed loudly as five American towns learned they had lost young men to a roadside bomb during heavy fighting two days earlier. Most citizens were by now so numb to such grim Iraq reports that the casualties barely made the national news. The same was true of a heated exchange at a Senate hearing involving new attorney general Michael Mukasey. He was trying to defend U.S. tactics for interrogation of terrorism suspects, tactics that most of the world had come to regard as torture—seriously harming America’s moral standing in the world. Meanwhile, it was a particularly bad day for the American mortgage industry, which had a major presence in Simi Valley through a large back office for troubled lender Countrywide Financial. That afternoon, the Wall Street rating agency Standard & Poor’s threatened to downgrade a whopping $500 billion of investments tied to bad home loans, while the largest bank in Europe, UBS AG, posted a quarterly loss of $14 billion because of its exposure to U.S. subprime mortgages. Such loans had fueled an exurban housing bubble in once-desolate places like the brown hillsides on the fringe of Ventura County around Simi Valley, and had been packaged and sold as high-risk securities.

That same day, nearly three thousand miles to the east, Jim Cramer—the popular, wild-eyed TV stock guru, and hardly a flaming liberal—was giving a speech at Bucknell University in which he traced the roots of the current mortgage crisis all the way back to the pro-business policies initiated nearly three decades earlier by America’s still popular—even beloved by some—fortieth president, the late Ronald Wilson Reagan. “Ever since the Reagan era,” Cramer told the students, “our nation has been regressing and repealing years and years’ worth of safety net and equal economic justice in the name of discrediting and dismantling the federal government’s missions to help solve our nation’s collective domestic woes.”

But there would be no questions about economic justice or the shrinking safety net at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, the epicenter of America’s political universe, what with California’s presidential primary—the crown jewel of the delegate bonanza known as Super Tuesday—less than a week away. The GOP’s Final Four evoked the parable about the blind man. Each seemed to represent a different appendage of the Republican elephant—the slicked-back businessman-turned-pol Mitt Romney, the good-humored former Baptist minister Mike Huckabee, the fiery fringe libertarian Ron Paul, and Vietnam War hero and POW John McCain, a self-described “straight talker” on a meandering political odyssey. Despite their unique and compelling stories and their considerable differences—both in background and in appeal to rival GOP voting blocs—each was apparently determined to stake out the same contrived identity. It was like an old black-and-white rerun of To Tell the Truth with four contestants all declaring: “My name is Ronald Reagan.”

CNN’s moderator, Anderson Cooper, followed a script for the night that was clearly inspired by this massive effort—including the construction of a special floor underneath the plane—to make Reagan’s Air Force One and thus the spirit of Reagan himself the stars of this slick TV production in the guise of a debate. The opening shot featured widow Nancy Reagan, eighty-six years old then, in a trademark red dress, greeting Cooper and then welcoming the candidates to Simi Valley. Cooper talked up the Boeing 707—the “stirring backdrop for our debate tonight”—and a camera toured the cabin, ending up at the jelly bean tray.

The whole ninety minutes was drenched in Reagan idolatry. It peaked later when Cooper asked the candidates about abortion and quoted from an entry in Reagan’s diary about the 1981 appointment of Sandra Day O’Connor to the Supreme Court. “And the Reagan Library has graciously allowed us to actually have the original Reagan diary right here on the desk,” he said. “I’m a little too nervous to actually even touch it, but that is Ronald Reagan’s original diary.”

It was this kind of 1980s hero worship that carried the debate and framed the discussion, rather than frank talk about the grim headlines of war and economic uncertainty that dominated the world of the present. It almost didn’t even seem bizarre that Cooper worked into the abortion issue by asking not about their stances in 2008 but about what they thought of Reagan’s nomination of the abortion-rights-friendly O’Connor some twenty-seven years earlier. The CNN host reminded the candidates of Reagan’s so-called eleventh commandment against speaking ill of fellow Republicans—adding gratuitously that “no one was tougher and more formidable in debates than Ronald Reagan”—and Cooper’s first question was an update of Reagan’s famous 1980 debate line “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?”

The candidates were asked several different ways whether they were conservative enough, or about the state of the modern Republican Party, matters that would be of little concern to the average voter. Meanwhile, the list of things that Cooper didn’t ask them about that night is mind-boggling: the high cost of gasoline, and energy policy. Health care. The increasingly powerful role that China, India, and other emerging countries are playing on the world stage. Iran, Afghanistan, or Israel. America’s image in the world in the face of outrage over torture and the detentions at Guantanamo Bay.

None of the candidates even seemed to notice what was left out, since they were too busy trying to hit the Reagan stage marks laid out in front of them. McCain, under conservative fire for opposing a GOP-backed tax cut in 2001, insisted he did so because it violated Reagan’s principles by not cutting government spending enough. “I was part of the Reagan revolution,” boasted McCain. “I was there with Jack Kemp and Phil Gramm and Warren Rudman and all these other fighters that wanted to change a terrible economic situation in America with ten percent unemployment and twenty percent interest rates. I was proud to be a foot soldier, support those tax cuts, and they had spending restraints associated with it.”

Later, asked his thoughts about then–Russian president Vladimir Putin, who had been an unknown KGB “foot soldier” in the Reagan era, Huckabee quickly migrated to a seemingly disconnected riff about U.S. military spending, adding: “And I do believe that President Reagan was right, you have peace through strength, not vulnerability.”

Paul, the one Republican who opposed the war in Iraq and some of the constitutional abuses of the George W. Bush presidency, was a little more circumspect about Reagan until Cooper asked the candidates explicitly about whether the late president would have endorsed any of them. “I supported Ronald Reagan in 1976, and there were only four members of Congress that did [against GOP incumbent president Gerald Ford]. And also in 1980. Ronald Reagan came and campaigned for me in 1978.”

But, for reasons that seemed obvious to his critics, no one was more eager to grab the Reagan mantle than Mitt Romney, so desperately anxious to calm wary conservatives because he had been governor of one of the nation’s most liberal states, Massachusetts. Asked the same question about whether Reagan would endorse him, he leapt in: “Absolutely.”

Ronald Reagan would look at the issues that are being debated right here and say, “One, we’re going to win in Iraq, and I’m not going to walk out of Iraq until we win in Iraq.” Ronald Reagan would say lower taxes. Ronald Reagan would say lower spending. Ronald Reagan would—is pro-life. He would also say “I want to have an amendment to protect marriage.” Ronald Reagan would say, as I do, that Washington is broken. And like Ronald Reagan, I’d go to Washington as an outsider—not owing favors, not lobbyists on every elbow. I would be able to be the independent outsider that Ronald Reagan was, and he brought change to Washington. Ronald Reagan would say, yes, let’s drill in ANWR. Ronald Reagan would say, no way are we going to have amnesty again. Ronald Reagan saw it, it didn’t work. Let’s not do it again. Ronald Reagan would say no to a fifty-cent-per-gallon charge on Americans for energy that the rest of the world doesn’t have to pay. Ronald Reagan would have said absolutely no way to McCain-Feingold. I would be with Ronald Reagan. And this party, it has a choice, what the heart and soul of this party is going to be, and it’s going to have to be in the house that Ronald Reagan built.

Spurred on in part by Cooper’s questions and the Reagan-inspired “stirring backdrop,” the candidates uttered the name “Reagan” some thirty-eight separate times over the course of the debate. Ironically, that was a sharp increase from the first time that the Republican presidential hopefuls had gathered in this very same hall in Simi Valley, on May 3, 2007, when a field of ten candidates drew a lot of media scrutiny and some ridicule from places like Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show for invoking Reagan nineteen times.

That first 2007 debate, nearly nine months earlier, saw almost comically desperate attempts by the candidates to link themselves to Reagan. Even the soon-to-flame-out front-runner, Rudy Giuliani, was so eager to free-associate Reagan that he ascribed the 1980s president with quasi-magical powers that could seemingly be harnessed to resolve the crises of the present.

Asked about Iran’s reported push to develop nuclear weapons in the late 2000s under its radical president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Giuliani said that the current Iranian president “has to look at an American president and he has to see Ronald Reagan. Remember, they looked in Ronald Reagan’s eyes, and in two minutes, they released the hostages.” He made it sound like a standoff scene from an old Western, the kind that was in vogue when Reagan himself had arrived in Hollywood in the 1930s. And just like in the movies, the scene that Giuliani imagined with Reagan and the Iranians had never really happened. But increasingly, that didn’t seem to matter. One historian wrote around the time of the CNN debate that discussions of Reagan in the 2000s increasingly reminded him of one of the last great Westerns, 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, in which a journalist famously notes that “when the facts become legend, print the legend.”

The legend of Ronald Reagan is one that few can resist, in politics and especially in the media. It has not only survived but flourished and grown quite separate from Reagan himself, who left the White House some two decades ago now, in 1989, who disappeared completely from the public eye with his poignant 1994 announcement that he was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, and who finally died in 2004, touching off a week-long festival of nationally televised, advertiser-supported grief that not only interrupted the reelection bid of George W. Bush but probably helped make it successful. Four years later, with the Republican Party at low ebb because of voter unrest over the war and economic woes that had festered the longer that Bush remained in the Oval Office, a posse of flawed candidates was hoping that lightning would strike again.

In the end, only one of the many candidates grasping for the Reagan mantle would be able to pull it down. That candidate, of course, was McCain, who would win a majority of the delegates in California and elsewhere on Super Tuesday and stake his claim to the nomination in a matter of days. In the winter blitzkrieg that carried the Arizona senator to the nomination, the McCain camp produced a TV ad called “True Conservatives,” which made a claim (called fantastic by some) that the younger Reagan had inspired him when he was a POW at the notorious Hanoi Hilton from 1967 to 1973, and repeated that McCain was a “foot soldier in the Reagan revolution.” What’s more, McCain ran ads attacking 2008-Reagan-worshipping Romney for 1994 remarks on Reagan that were highly critical. McCain’s tag line: “If we can’t trust Mitt Romney on Ronald Reagan, how can we trust him to lead America?” The push was the key to McCain’s victory against long odds—his campaign had nearly run out of money in 2007, and he faced withering assaults from right-wing opinion makers, such as radio’s Rush Limbaugh, who claimed McCain was a phony conservative. The Reagan comparisons had undercut the notion that McCain was too liberal or too old for the job. Now McCain hoped he would write the epilogue to the legend of Reagan, which had been printed so many times and was deeply ingrained with the electorate.

The legend of Ronald Reagan has a story line that would have surely wowed any studio executive hearing a pitch: Small-town lifeguard and varsity football player with a loving, churchgoing mother and a roguish, hard-drinking dad heads for Hollywood and becomes a movie star—and when that dream stalls out, comes up with a second act that is bigger and more audacious than the first. The hero undergoes a 180-degree political conversion and becomes a fiery, reactionary public speaker, then a governor, and then, finally, improbably, the president of the world’s greatest superpower. And not just any president, but the noblest commander in chief of the postwar era, a man who won an ideological war at home—reversing a half century of growing government and rising taxes—and then won a cold war abroad, the global conflict between freedom and totalitarian communism, before riding off into the Pacific sunset. And like It’s a Wonderful Life, the story line became more iconic in the frequent rebroadcasts than when it was actually in the theaters. The postpresidency Reagan became not just the most revered figure in modern American history but so much more—a kind of homespun public intellectual, as expressed through handwritten diaries and radio commentaries, a humanitarian who exchanged letters with everyday Americans, someone who was as much a man of God as a man of politics.

It was this powerful and increasingly ingrained story that was both celebrated and retold in Simi Valley and on CNN on this particular night—and given the powerful narrative, who could blame presidential candidates and TV producers for embracing it? Visitors to the debate at the Reagan Library filed past a larger-than-life bronze statue called After the Ride, which depicts Reagan not as a political leader or even as a movie star but as a figure of popular imagination—a cowboy in blue jeans, Stetson hat in hand. Simi Valley might be the capitol of the Ronald Reagan legend, but by the winter of 2008 it was hardly the only place where candidates could go to stake their case as true heir to the political legacy of the man many still call “the Gipper,” after his most famous Hollywood role from 1940, as dying Notre Dame football star George Gipp.

Indeed, even though it’s been just a few short years since Reagan joined Gipp and departed this world, it seems as if one could drive from coast to coast on one long Ronald Reagan Boulevard, sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically, especially across the hot asphalt of the Sunbelt, where Reagan and his acolytes worked so hard to build up a permanent GOP majority. You could start your tour down the Ronald Reagan Freeway, the main highway leading out of Simi Valley. The first stops could be a couple of Ronald Reagan Elementary Schools, one down in the Central Valley in Bakersfield—billed as home of “The Patriots”—and one in the Valley town of Chowchilla, where the new structure with a bust of the fortieth president was dedicated in September 2007, with the necessary fanfare of a military helicopter bearing an American flag that had been flown over the U.S. Capitol. Be sure to stop in the small town of Temecula, where a sports park that Reagan mentioned in a speech to raise money for the 1984 Olympics is now named for the late president, or at Ronald Reagan Park in Diamond Bar in Orange County, the heart of his political base. Another small shrine erected at the time of his passing is the Ronald Reagan Community Center in El Cajon, California, a small community near San Diego that Reagan apparently never visited, even in eight years as the state’s governor. The local newspaper did note a connection, however: Nancy Reagan showed up once to select an Olaf Wieghorst painting for her husband’s birthday. Said a glib archivist from the Reagan Library at the time of the 2004 renaming: “I don’t know if he’s ever been to El Cajon, but I do know he set policies as governor that affected El Cajon and its citizens.”

Of course, given Reagan’s long history with the state...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- CONTENTS

- CHAPTER ONE: Ronald Reagan Boulevard

- CHAPTER SIX: Rolling Back Reagan

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR