![]()

Chapter One

SOPHIA KNEW TOLSTOY her entire life: he was her mother’s childhood friend. But the relationship between the two families went back even further. Sophia’s maternal grandfather, Alexander Islenev, was a neighbor and hunting companion of Tolstoy’s father, Nicholas, who lived on the family estate, Yasnaya Polyana, near Tula. The Islenevs and the Tolstoys visited each other during holidays, name days, and birthdays, attended by a throng of servants, cooks, and lackeys.1 In his first novel, Childhood, which brought him recognition, Tolstoy portrayed both families.

Sophia’s maternal grandmother was the daughter of a well-known statesman, Peter Zavadovsky, a favorite of Catherine the Great. The empress showered Zavadovsky with promotions and awards, appointing him minister of education, senator, and count of the Holy Roman Empire. Zavadovsky’s palace, Lyalichi at Ekaterinodar,2 in southern Russia, was designed on the empress’s orders by a renowned Italian architect.3 Zavadovsky’s palace, comprising 250 rooms, was a desolate place: he complained it felt like an aviary for crows. He asked Catherine’s permission to marry Countess Vera Apraksina, later appointed a lady-in-waiting. The couple’s only surviving daughter was Countess Sophia Zavadovsky.

The countess’s story was often heard in the family: in her teens she was first married off to Prince Kozlovsky, soon discovering he was an alcoholic. A divorce was unfeasible, but she left her husband for a common-law union with Islenev, whose estate neighbored the Tolstoys’. The countess secretly married Islenev in a parish church, but the bigamy was discovered and the couple’s six children were declared illegitimate. They received the improvised name Islavin and were assigned to the merchant class. Lyubov Alexandrovna Islavin, Sophia’s mother, was one of the children. She danced with Tolstoy on his birthdays and was his sister’s best friend. In Childhood Tolstoy described something akin to first love toward the girl who would become his mother-in-law. He once pushed her from a low balcony for talking to another boy; the fall nearly crippled her. When Tolstoy became a celebrated writer, Lyubochka,4 as he called her, still talked down to him even though she was only two years his senior.

Like all the Islavin children, Lyubov Alexandrovna was painfully aware of her illegitimacy and semiaristocratic origin. At sixteen, she married a physician of German descent, Andrei Yevstafievich Behrs, twenty years her senior. The marriage was seen by her family as a misalliance: the nobility looked down on the medical profession, equating it with that of musicians, the very bottom.

Although Sophia’s parents met under adverse circumstances, these proved ideal for romance. Her mother was dangerously ill when Behrs, a Moscow physician stopping in the provincial city of Tula, was summoned to examine her. Behrs was actually heading to Turgenev’s estate in the neighboring Oryol when he treated Lyubochka and proposed to her. The meeting was destined to link two of the greatest novelists, Tolstoy and Turgenev.

Sophia’s ancestors on her father’s side were German Lutherans. Her great-grandfather Ivan Behrs (Johann Bärs), a cavalry captain in the Austrian army, was invited to Russia as a military instructor by Empress Elizabeth I. He died shortly after, in 1758. Behrs’s immediate family knew little about his wife, Maria. Their only son, Evstafy, raised and educated by a German foster family, became a successful apothecary. By the time he married Elizaveta Wulfert, a descendant of Westphalian nobility, Evstafy owned two stone houses in Moscow. The couple’s sons, Alexander and Andrei,5 born in 1807 and 1808, were baptized Evangelical Lutheran.

Sophia’s father, Andrei Behrs, was four when Napoleon invaded and his family fled the burning Moscow. Evstafy stayed behind hoping to save his property but could only helplessly watch the destruction of his drugstore and the stone houses. Fleeing in disguise, with a servant and two pistols, he was captured by the French but managed to escape; these events were later woven into War and Peace.

After the war, Evstafy reopened a drugstore, but things were never the same. He entered government service and his wife embroidered purses, all to make ends meet. The couple’s two sons were educated as charity boys in a private boarding school. Brilliant and ambitious, Alexander and Andrei entered the medical school at Moscow University, aged fifteen and fourteen. The careers of Sophia’s uncle and father were similar: both attained high rank in the civil service, earning them hereditary noble titles and identical promotions and awards.

While still a medical student, Andrei Behrs was invited to accompany the Turgenev family on a journey abroad. His family knew Varvara Petrovna Turgenev, née Lutovinova, heiress to an enormous fortune.6 Behrs would later reminisce about their travel through Europe, medical lectures, and performances of the Italian opera in Paris featuring the legendary Maria Malibran.7

According to Tolstoy, Behrs was “a very straightforward, honest and quick-tempered man” and “a big womanizer.”8 As a bachelor, he sired several children and had a daughter by Varvara Turgenev in 1833.9 In childhood, Sophia met Lizanka René, her father’s daughter by a French governess, and fearing that she also might be illegitimate, she compelled Behrs to produce her birth certificate.10

After his marriage to Lyubov Alexandrovna in 1842, Behrs, already court physician, was also appointed a supernumerary doctor of Moscow theaters. Behrs was rarely seen at home, juggling two jobs, a private practice, and an extensive social life. The children inherited his deep sense of duty and almost religious devotion to work, attributed to his Lutheran upbringing. For Sophia, daily toil was essential; to feel virtuous she would list a multitude of chores to be performed during the day.

The family lived in a Kremlin apartment, adjacent to the ancient Poteshny (Amusement) Palace, a three-story mansion of white stone with carved jambs. Originally used as a court theater by the first Romanov tsars, the palace was later utilized as an ordnance house in the mid-nineteenth century and was remodeled to accommodate apartments for Kremlin staff. The rooms were modest, like those of rank-and-file officials. The windows faced the Troitsky Tower by the main entrance to Red Square. Illuminated at night, it glowed “from top to bottom, as if made of diamonds.”

The house in the Kremlin where Sophia grew up, by the Troitsky Tower and the main entrance to Red Square. Photo by the author.

Every summer, the family retreated to their government dacha, or country house, in Pokrovskoe-Streshnevo, near Moscow. In her novella “Song without Words” Sophia depicts the beginning of the summer season and the exodus from Moscow, then a provincial city:

A procession of carts laden with furniture, featherbeds, baby carriages, plants, and trunks; cows tied by their horns; the belongings of city residents moving to the dachas stretched along the Moscow streets to the city gates.11

Sophia was born at the dacha on August 22, 1844, the second of thirteen children, five of whom died in infancy. The four older children, born a year apart, were Liza, Sophia, Tanya, and brother Sasha. After an interval came four younger boys, Petya, Vladimir, Stepan, and Vyacheslav, still a baby when Sophia married. Her happiest memories were of the summers at the dacha and of her freedom there, enjoyed to the full when compared with their more restricted city life. In Moscow, the girls had to be escorted on their walks by their father’s batman, in military uniform and helmet.

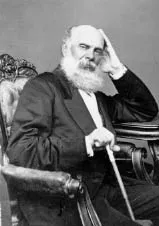

Much of the summer was spent with their father’s hunting dogs, black setters and white pointers with reddish yellow spots. Behrs trained the valuable setter pups and sent them as gifts to his friends and to the tsar. By then, their father was an old man: the children remembered him as “tall and erect, with large blue eyes and a long grey beard.” At the dacha, he drove in his charabanc or walked with a gun over his shoulder and a setter by his side.12

Sophia’s father, Andrei Behrs, in 1862.

Their dachas were built on land that had belonged to the old Streshnev clan for more than two centuries. The last heir, an old, semiparalyzed man, permitted the Behrs children to raid his garden and roam in the woods. From their second-floor bedroom window, the girls had a view of the old noble mansion and its ponds, the winding road, and the Pokrovskoe church with its green cupolas. Tolstoy would later remember how he used to drive along this winding road to Sophia’s dacha after he had fallen in love with her. The two of them would also drive on the same road at the sundown of their lives, taking their youngest son to the cemetery.

Sophia’s uncle Konstantin Islavin, a childhood friend of Tolstoy and a frequent guest at their dacha, sparked her interest in music. A talented pianist, Islavin impressed Nikolai Rubinstein, founder of the Moscow Conservatory, with his interpretation of Chopin; yet he failed his examination. As an illegitimate son, he had neither property nor a family of his own; his insecurity became an obstacle to a career of any kind. He lived through the charity of relatives. In childhood, his stays were a delight for Sophia and her siblings: “He introduced us to all the arts and for the rest of my life I maintained … a strong desire for learning, eager to understand every type of creativity.” They danced to his piano improvisations. “I remember the delight I experienced in childhood when Uncle Kostya played Chopin on the piano, and my mother sang in her high soprano, with a pleasant timbre, Alyab´ev’s ‘The Nightingale’ or a gypsy song ‘Aren’t You My Soul, Fair Maiden.’” Once, he called at their dacha with Tolstoy, when the cook was having his midday nap. Sophia and her sister Liza heated up the stove and made dinner for their guests. Tolstoy praised them: “What sweet girls … How well they fed us.”

Turgenev also visited her family whenever he was in Russia. At dinners he told of his hunting adventures, describing masterfully “the beautiful scenery, the setting of the sun, or a wise hunting dog.”13 He was very tall and Sophia, nearsighted, could only see his face when he bent over to pick her up. “He would lift us into the air with his large hands, give us a kiss, and always tell something interesting.”

The Behrs lived in the part of Moscow that had witnessed the Napoleon invasion. In War and Peace, which Sophia would later copy out, Napoleon looks through his binoculars at the Kremlin towers, expecting a delegation with the keys to the city. Those medieval towers could be seen from her window and she dreamt of an excursion through them and the Wall Walk, a fighting platform atop the walls.

Behrs obtained special permission for his children to go on a tour of the towers, with two grenadiers as guides. Troitsky Tower, the closest to their home, was known for its notorious prison cells. They examined the mysterious passages and the narrow stone staircases, and heard stories of how the criminals were walled up there. As they climbed the staircase of the Spassky Tower to see the mechanism of the big clock, it began to hiss, roar, and ring; “the sound was deafening.”

When Nicholas I drove by their Kremlin home, the Behrs children bowed from their windows; he smiled and saluted back. As children of a court official, they did gymnastics in the Great Kremlin Palace and amused themselves by running through the corridors, which were adorned with paintings by Bacciarelli, Titian, Rubens, and others. While standing on the balcony overlooking his chamber, they watched the new emperor Alexander II dine, and once heard him rebuke his lackey, “Fool! I ordered you to bring me beer!”

Despite their noble upbringing, the Behrs children were assigned chores, took turns in the kitchen, sewed, and taught their younger siblings. Their Petersburg cousins, the children of Uncle Alexander and his Scottish wife, Rebecca Pinkerton, were raised the same way. Sophia and her siblings were told that they would have to earn their living because they had no fortune and the family was large. She was eager to help with various chores, becoming her mother’s right hand: “If something had to be lifted, moved, carried … or my father’s or mother’s room had to be tidied up—they would choose me as the healthiest, strongest girl who didn’t care much for learning.”

The Behrs were lavishly hospitable: their relatives and friends came to stay for months. The house staff, consisting of ten or twelve, also lived in the apartment. The coachman and the housekeeper, Stepanida Trifonovna, with whom Tolstoy would stop to talk, were treated as part of the family. The housekeeper, in charge of all holiday baking and preparations, was remembered for her enormous Easter cakes.

The family attended services at the Church of the Virgin Birth, the chapel for the grand dukes and tsaritzas. The church’s main entrance had been walled up and could only be entered through the winter garden, adjacent to the Great Kremlin Palace. At Easter, the sisters ran through the palace corridors and the garden, anticipating the magnificent choir and the whooping toll from the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, answered by festive pealing across Moscow. Orthodox services in the Kremlin were solemn and beautiful, inspiring a mood for prayer and tears of ecstasy. At home, Sophia liked to pray in solitude, kneeling for hours before an icon. The stable world of her childhood, with its ancient faith and customs, remained a stronghold through the many trials of her marriage. Her memory would bring her back to the world that had inspired her belief “in the importance of life.”14

Her father’s German Lutheran culture influenced her less, although her grandmother Elizaveta Wulfert lived with the family. Every Sunday, the girls went to her bedroom to play with the fabulous dolls she ordered from Petersburg, along with garments and toy furniture. Sophia, however, preferred musical toys, which she herself assembled. She was also a passionate collector of stones and herbaria, a hobby she would resume in old age.

Sophia’s sister Liza, diligent and bookish, was nicknamed “the professor” in the family. She was in charge of policing her siblings, which made her unpopular. Tanya, the youngest and everyone’s favorite, was Sophia’s confidante. She would describe Soph...