THE LIBERATION OF Europe may have begun as early as November 1942, on the banks of the Volga river at Stalingrad, when the Soviet Red Army checked Nazi Germany’s advance into Central Asia and began the long, murderous fight that would expel the German invaders from the Soviet Union and bring the Russians across 1,500 bloody miles to Berlin. Or it may have begun with the Anglo-American landings in North Africa, also in November 1942, a deft operation that pointed the blade of the Allied spear-head into Germany’s southern flank and opened the way to the invasion of southern Italy in July 1943. Perhaps the liberation began in earnest when the Red Army crossed the prewar Polish border in January 1944, or when American troops entered Rome in June 1944. These are all plausible candidates for the status of “starting point,” for the liberation of Europe was a global process, the pressing inward toward Berlin of millions of soldiers, from all directions, gradually tightening a choke hold on the Third Reich. Yet in popular imagination, and most historical writing, the liberation of Europe commenced on that wet gray morning in the rolling surf off the coast of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Here, in France, came the long-awaited, long-planned Second Front, designed to complement the massive thrusts of the Red Army into Germany from the east. This was the moment that European civilians, suffering under German occupation, had awaited for years, the moment when the decisive battle against Germany would be opened, the start of a continental campaign that would bring about the final defeat of the malevolent, depraved Nazi regime. This is where our story of liberation begins.

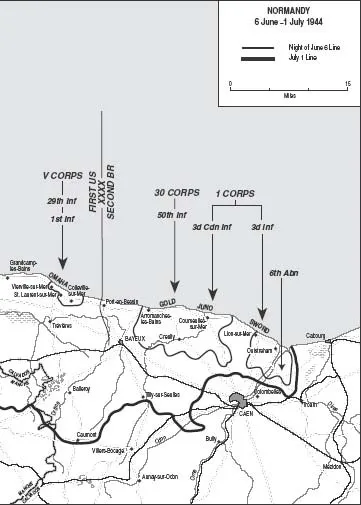

The great Allied armada that set out across the English Channel on June 6 comprised some 5,000 vessels of all sorts, from hulking, monstrous battleships, cruisers, and destroyers to a vast array of small landing craft. On board, they carried over 100,000 soldiers—American, English, Welsh, Scotch, Irish, Canadians, Poles, and a few Belgians, Dutch, French, and Norwegians—to landing sites along twenty miles of coastline in the French départements (departments) of Calvados and Manche. The overall supreme commander of Operation Overlord was General Dwight D. Eisenhower; the ground commander of the landing forces was an Englishman, General Sir Bernard Law Montgomery. On June 6, the landing forces were all grouped together in the 21st Army Group under Montgomery’s command. The British Second Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey, took aim at three beaches, code-named Sword, Juno, and Gold, running from the villages of Ouistreham in the east to Arromanches in the west. The Anglo-Canadian forces that splashed ashore here faced moderate resistance but within a few hours had established three beachheads and made contact with the British 6th Airborne Division, which had been dropped across the Orne river to secure the eastern flanks. The British suffered approximately 1,000 casualties on Gold beach and the same number on Sword; 600 airborne troops were killed or wounded, and 600 more were missing; 100 glider pilots also became casualties. The Canadians at Juno beach suffered 340 killed, 574 wounded, and 47 taken prisoner. Twenty-four hours after the landings, British forces had taken the town of Bayeux almost unopposed and were pushing on toward the city of Caen.

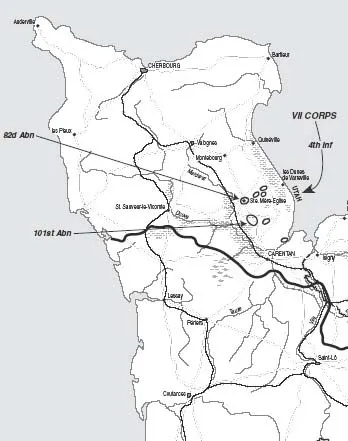

To the west, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley’s U.S. First Army landed on two beaches, Omaha and Utah. Utah beach was on the western flank of the Allied assault, running along the coast of the Cotentin peninsula. The beach here was thinly defended; three regimental combat teams of the 4th Division faced negligible fire from the German positions and they moved inland in search of the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions with whom they were supposed to link up. These airborne landings, which had commenced late at night on the 5th, had been badly scattered and it was some days before any cohesion came to this sector; yet the losses sustained on Utah were relatively small. The picture on Omaha beach was far more serious. The 1st and 29th divisions of Bradley’s landing force, hitting the beaches between Port-en-Bessin and Vierville-sur-Mer, ran straight into the teeth of well-defended German batteries that had not been softened up by the preliminary air and naval bombardments. The cliffs along Omaha, running up from a stony beach, rise some hundred to two hundred feet, and provided excellent cover for the defenders, who had created extensive trenches and concrete pillbox firing positions; moreover, 27 out of 32 of the “swimming” amphibious DD tanks that were meant to provide armor support for the infantry sank in choppy seas during the landing. The beach and waters were packed with obstacles and mines on which landing craft snagged, blocking the way for those behind. Many heavily burdened soldiers whose craft spilled them into the water sank and drowned. With extraordinary courage, small numbers of soldiers, realizing that to remain on the beach under German fire would surely get them killed, began to fight their way up the craggy hillside and into the narrow ravines that led from the beaches up the hills. Slowly they gained a foothold. The horror on Omaha, which had seemed an eternity to those pinned down there, had lasted less than four hours; by 11:00 A.M. Vierville was in American hands. At the end of the day, a narrow beachhead had been established, but it had cost the Americans dearly. While there had been but 197 casualties on Utah, over 2,000 men were wounded or killed on Omaha beach. Overall, 1,465 American soldiers were killed on D-Day, 3,184 were wounded, 1,928 were listed as missing, and 26 were captured.1

The view of Omaha beach from an American landing craft, June 6, 1944. FDR Library

The Omaha landings had been something close to a catastrophe, and the broad territorial objectives of the Allied landings had not been attained anywhere on any beach on D-Day. Even so, the overall strategic picture twenty-four hours after D-Day was good. The landings successfully created a beachhead that could be defended against counterattack, and the planned buildup of additional Allied forces could proceed apace. Casualties, totaling some 10,000 men, had been far smaller than General Eisenhower had anticipated. But over the following weeks and months, the realities of the huge task that lay ahead began to sink in. The first disappointments came on the eastern flank, where the British, whose landings had gone so well, were unable to seize the city of Caen, which lay on the axis that the Allies had hoped to follow farther into France. In the three days after the landings, Canadian and British forces were badly mauled by the 12th SS Panzer Division, which tried desperately to push the invaders back into the sea; by June 10, the Germans, bolstered by the swift arrival of the Panzer Lehr Division and the 21st Panzer Division, took up defensive positions in front of Caen. In the coming weeks, repeated efforts by Montgomery’s forces to outflank Caen, at Tilly-sur-Seulles and Villers-Bocage, failed and the struggle for Caen turned into a desperate yard-by-yard fight that many likened to the western front in the First World War. The daring and surprise of the D-Day landings had been completely lost.

The picture was only marginally better on the western flank. After consolidating the Utah and Omaha beachheads, the American VII Corps under Major General J. Lawton Collins attacked westward to cut the Cotentin peninsula in half, then thrust north to capture the port of Cherbourg on June 27. Despite this success, the picture across Normandy was discouraging for General Eisenhower. The Germans had systematically, expertly reduced Cherbourg to rubble, which interfered with the logistical supply plan. By late June, conditions on the ground had settled into a bloody stalemate, as the Germans made superb use of the defensive advantages they possessed, particularly the thick, ancient hedgerows that divided the countryside up into nearly impenetrable squares. The Americans found themselves fighting for every yard across a landscape that looked something like a gigantic ice-cube tray: each square had to be penetrated and seized, one by one. This slow, costly fighting made June and July “a difficult period for all of us,” General Eisenhower wrote later.2 Yet gradually, two elements in the Allied arsenal began to tell in the battle: the steady buildup of men and materiel through the massive Anglo-American naval forces that continued to pour supplies through the beachheads; and the punishing blows delivered daily to the Germans by the dominant Allied air forces. By July 2, there were about one million Allied soldiers in Normandy, including thirteen American, eleven British, and one Canadian division. Over 560,000 tons of supplies had been landed along with 171,000 vehicles.3 While the Germans proved able to out-fight the Allies on the ground in Normandy, they could not easily replace the men and materiel they lost; nor could they hide from the Allied tactical air attack. The battle in Normandy settled into a long, slow battle of attrition, just what the Germans could not afford.

By late July, the allies fielded 1.4 million soldiers in Normandy, about twice the number of German soldiers engaged in the battle, yet were still stuck in positions they had planned to occupy just five days after D-Day. The battle had been far slower and bloodier than expected, with the terrain of Normandy inhibiting Allied maneuvers. But on July 25, with the bulk of the German forces engaged in the Caen area, the American First Army, deployed along a line running west from Saint-Lô to the coast, staged the great breakout that would change the dynamic of the campaign, and the war. Following a colossal (and sloppy) carpet bombing of the German defensive positions just west of Saint-Lô, the Americans ripped open a gap in the German line and plunged forward, rushing south and west toward Avranches, thus opening the way into Brittany and, more importantly, threatening to envelop the German army in Normandy. Fending off a ferocious German counteroffensive at Mortain between August 7 and 12, the U.S. First and Third armies punched eastward and caught the Germans in a massive pincer, between the Anglo-Canadian forces in the north, at Falaise, and their own troops in the south at Argentan. Under sustained air and ground attack, the German army was caught in a rapidly constricting pocket and brutally pummeled. The Germans lost 10,000 men killed in the furnace of Falaise, and another 50,000 were captured. But brilliant German defensive fighting kept the Falaise pocket open just long enough to allow perhaps 100,000 Germans to slip away and escape across the Seine river. They joined a massive exodus of all German forces in France, some 240,000 troops, who rushed headlong through France and Belgium on into Germany itself, where they would regroup behind the Siegfried Line and fight another day. Though victory in Normandy had not brought about the total destruction of the German army in France, it dealt it a severe blow and clearly signaled that the liberation of Europe was at hand.

By August 25, when the Allied forces reached the river Seine and marched into Paris, the American and British commanders could look with satisfaction on the victory they had achieved since the landings in early June. The Germans had lost 1,500 tanks, 3,500 guns, and 20,000 vehicles. There were 240,000 German soldiers dead or wounded, and another 200,000 had been taken prisoner. More than forty German divisions had been destroyed, and Hitler could not make good this scale of loss. By the first of September, virtually all of France had been cleared of the German forces and on September 4, the Belgian capital Brussels and vital port city of Antwerp were liberated. The Allies paid for their victory in Normandy with the lives of 36,976 of their own soldiers.

ABOUT TEN DAYS after the Allied landings on the beaches of Normandy, Ernie Pyle, the legendary American war correspondent, took a jeep ride through the Norman countryside. “It was too wonderfully beautiful to be the scene of a war,” he wrote. “Someday I would like to cover a war in a country that is as ugly as war itself.” Of course, Pyle saw more than the gently rolling pastures, the wheat fields, and the fruit trees: the region had been shattered by heavy bombardments before and during the D-Day invasion, and he wrote about the ruined hamlets and towns eloquently. But he also told stories that neatly framed the basic American understanding of what the war was really about. Arriving at an old school that was being used as a prison for German POWs, he got out to have a look around.

Ernie Pyle’s newspaper columns for the Scripps-Howard syndicate, written from North Africa, Italy, and France, sketched out for avid readers in the United States detailed portraits of average American soldiers—their concerns and their personalities, their uncomplicated nature and basic kindness. Pyle was honest enough a reporter to write about screw-ups, about wrecked French towns, about how frightened soldiers under fire normally were, and about the moment he found himself caught under the massive American bombing run near Saint-Lô on July 25 that inadvertently killed over a hundred GIs. But Pyle became treasured for his ability to paint moving portraits of these “good boys” and the cause for which they fought. He traveled with these young soldiers, slept out in the cold with them, cooked eggs for them, shared anxieties with them, and in April 1945, while in the Pacific, Pyle died with them, the victim of a Japanese sniper’s bullet. He was mourned by the nation precisely because his writing reflected a tone that American readers found comforting: unpretentious, gently ironic, and filled with quiet assurance that the cause was just and that democracy would win through in the end. Pyle, in writing the rose story, told Americans that the liberators had been welcomed to France warmly and that through the horrors of war, one could glimpse some basic human decency still alive in Europe.

And yet, Pyle doesn’t tell us much about that young man who offered him the rose. What had become of his family? Had his home been damaged in the invasion? What became of him after the Americans had passed through? Was he, indeed, a Norman? Pyle might not have known if this young farmer was a refugee from any one of the cities nearby that had been evacuated during the fighting, or even if he had been a Pole, or a Russian, transported into France to labor on behalf of the German occupiers as they built up their now-breached Atlantic Wall. In fact, Pyle didn’t write much about French civilians in Normandy. In his articles, civilians remain, like that farmer, mute, decent, but alien. Pyle offered no insight into how civilians in the region viewed these gun-toting American boys who arrived in such huge numbers, or how they dealt with the soldiers’ petty thefts, periodic looting, and frequent drunkenness; nor did he write much about the shocking viole...