![]()

1

How Much

Is Too Much?

The Rule of Celebrity Hairdressers

Frédéric Fekkai jets between New York and Los Angeles so that faithful clients on both coasts can have access to his hairstyling genius. On May 18, 1993, Air Force One remained parked at LAX, shutting down two of the airport’s four runways and causing flights to be diverted for nearly an hour, while Cristophe of Beverly Hills clipped the locks of the president of the United States. (The Washington Post called the trim “the most famous haircut since Samson.”) All this Bonfire of the Vanities—style excess was not, as we might think, unimaginable before the boom years in New York City. It has been the way of the world—or at least of a very small segment of it—ever since, in mid-seventeenth-century France, a new profession appeared on the fashion scene: ladies’ hairdresser. From then on, hairdos had names, styles changed frequently, there were A-list hairdressers, and some styles were even named for those who set the tone, the celebrities of the day—the King’s mistress, for example. For the first time, those who invented new styles began to make such pronouncements as this year hair will be curlier or this season only long tresses are in.

Prior to that time, the field of hairstyling was resolutely sex-specific. The first barbers were medical men, ancestors of the modern-day surgeon. Then, in 1659, a royal edict created the profession “barber-wig maker,” and new-style barbers, who played no medical role and dealt exclusively with beards and men’s hair, began to open shops in Paris, where they worked only on men.

Women’s needs were still taken care of by their ladies’ maids; no one imagined that there would soon be a profession devoted to ladies’ hair, much less that men would ever be allowed to engage in the intimate gesture of touching a woman’s head. Women’s hairdos were relatively simple affairs; there was little sense of trends; styles changed slowly and never had a broad impact. No one could have imagined a style that everyone absolutely had to have once it had been decreed to be the look of the season. Then, in one fell swoop, Monsieur Champagne swept away centuries of prejudice and became the original brand name in hairdressing. From that moment on, a look produced by big-ticket hairdressers earned bragging rights for the lucky few with access to the new styling magic.

The revolution in women’s hairstyling that Champagne brought about was a crucial first step toward the birth of that quintessential French phenomenon, couture. Crucial to couture’s stranglehold is the notion that, when a woman wears a certain style of dress, it will immediately be recognized by all those in the know as the creation of a particular designer. Haute coiffure invented this notion. For the first time ever, a stylist’s name—that of Champagne—determined the value of a hairdo. As the title character in a play based on Champagne’s life put it, “Other stylists may have their own ideas, / But I always know that my method / Will dictate fashion for everyone.”

Before there was couture, before there were the luxe bijous of the grand joailliers, there were the new hairdos of the minute. If a woman made an appearance with her hair styled in a certain way, the ladies who lunched all identified the magic touch of le sieur Champagne, hairdresser of the rich and famous. The moment when hairstyles “signed” by their creator were first recognized clearly indicated that Frenchwomen were ready to take on what women all over the world have considered ever since to be their essential role: that of always knowing just how they have to look for every new season and also exactly which designer will guarantee that they will be instantly recognized as having that information. Couture’s tyranny had begun.

A new word was created to describe Champagne’s profession: coiffeur, the term still used in French. Coiffeur, and then its feminine form, coiffeuse, were created to reflect the existence of a new profession: the original coiffeurs and coiffeuses worked exclusively on ladies’ hairstyles and head styles. I say “head styles” because, in the seventeenth century, there was more to the coiffeur’s job than just dealing with hair: the coiffure, which now means simply “a hairdo,” referred to everything covering the head and included many things besides hair.

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, women all over Europe wore coiffes—wimples, bonnets, and other uses of fabric to cover a large part or even all of the head. (Covering the hair was considered a gesture of female modesty.) In Paris, beginning in the 1660s, the same word, coiffe, began to be used for an entirely new phenomenon, and the total production, the coiffure, began to resemble the hairdresser’s masterpiece as we know it today. True, the coiffe most often still featured material. From this point on, however, the fabric—typically bits of taffeta or lace—was no longer used primarily to cover the hair but to make it look its best; it had become a fashion accessory meant to add volume to the hair or to help keep a bunch of particularly fetching curls looking as though they had just happened to fall that way naturally. The new profession caught on quickly: the term coiffeur was first used in 1663, to describe Champagne; by 1694, the French Academy’s very official dictionary of the French language recognized the reign of ladies’ hairdressers by speaking of “coiffeurs and coiffeuses à la mode.”

The members of the new profession were the first true hair artists: it was their job not only to make their clients look as fabulous as possible but to be constantly imagining new ways of combining all kinds of hair—for coiffes could include hairpieces and what are now called extensions—and fabric. The proof of their success is the fairly dizzying progression of hair creations that followed one another on the French fashion scene at the seventeenth century’s end. In each case, the minute the first woman appeared coiffed in the new way, the style received a name, and others—initially in Paris and then all over Europe—would rush to copy it. For the first time ever, there were seasons for hairstyles in the same way that we now think about fashion collections that dictate what women will wear the following year.

In the beginning, coiffeur was a profession of one. About Champagne himself, we know nothing, not even his real name. About his life as a coiffeur, however, we know a great deal. Some of the most prominent Parisiennes of the day were so outrageously enraptured with Champagne’s capillary magic that his male contemporaries were driven to scathing satires of the budding relationship between hairdresser and celebrity client. The most remarkable of these is a comedy, Champagne le coiffeur—this seems to be the first time the word coiffeur was used in print—staged at the Théâtre du Marais in 1663, shortly after the real coiffeur’s death.

By all accounts, Champagne could have been the model for the role of bed-hopping artist of the tresses that Warren Beatty incarnated over three centuries later in Shampoo. Champagne apparently bragged incessantly of having enjoyed the favors of the great ladies whose coiffes he maintained. The play turns on this image of the coiffeur as inveterate ladies’ man: Champagne has convinced the only daughter of a wealthy man to elope with him. And the daughter, Elise, is surely the first hairstylist groupie; the author, Boucher, includes a list of celebrity hairstylists Elise allegedly visits on a daily basis to be certain of always being coiffed on the cutting edge. In other aspects as well, the fictional Champagne lives up to the legend of his real-life model. He boasts constantly about how desperately the rich and famous depend on him. Near the end of the play, he even launches into a detailed account of the anecdote that in his day received as much, and similarly mocking, coverage as the tale of Clinton’s rendezvous with Cristophe did in our day.

When Princess Marie de Gonzague left Paris for Warsaw to marry Wladyslaw IV, king of Poland, she was considered an aging beauty—over thirty, by which time, according to seventeenth-century standards, she was disastrously near the beginning of the end. When the marriage was celebrated by proxy in Paris, Champagne helped a lady-in-waiting place the crown on the princess’s head—presumably so that her coiffure wouldn’t be mussed. Then, by his own account, the princess begged the coiffeur to accompany her to Poland in order to keep her hair, at least, perfect at all times. It was clearly the first time that anyone had considered that something as simple as a hairstyle could become an affair of state. Both contemporary newspapers and satirists of the French scene such as Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux gave Champagne considerable press, winning him the kind of status previously unimaginable for someone who worked with others’ hair. In the play, for example, other characters refer to him with respect, as “Monsieur Champagne.”

Celebrity status meant considerable financial rewards. The fictional Champagne says that he went along for the ride to Poland “in the hope of great gain” and adds that “he was well paid for his pains.” Tallemant claimed that the real-life Champagne refused to accept money for his services—unlike other well-known coiffeurs of his day who, just as Cristophe did for the Clinton family, had service contracts with their celebrity clients. Champagne guessed—quite accurately—that his method would cause his clientele of stylish princesses to outdo one another in showering him with expensive gifts: “While he was styling a lady’s hair, he would tell her about another lady’s presents, and when he wasn’t satisfied with them, he would add: ‘She can beg me to come now; she no longer has any hold on me.’” “The foolish woman,” Tallemant concludes, “terrified that he might treat her the same way, gave him twice as much as she would have done.” The era of the eight-hundred-dollar haircut had dawned.

In true prima donna fashion, Champagne is said to have rewarded such slavish fidelity by humiliating his benefactors. He had all the attitude associated with today’s most sought after stylists. On a whim, he would just walk out, leaving a client with her coiffe only half assembled. One day, while he was doing the hair of a woman with a particularly large nose, he suddenly turned on her: “You know, with a nose like that, you’ll never look good, no matter how I style your hair.” And to add insult to injury, he addressed her using the familiar tu form.

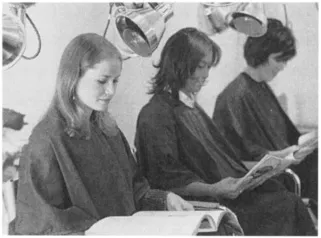

Champagne’s high-profile styling revolutionized the way the business of doing a woman’s hair took place. Until then, when a woman wanted to assemble a new coiffe, a female merchant, known as a perruquière, or wig maker, brought various hair ornaments to her home for her to try on. Before the end of the seventeenth century, the best-known coiffeurs and coiffeuses, while they continued to make house calls for their most famous clients, also had shops, where they could reach a far wider clientele, showing off a much expanded range of hair accessories and styling coiffes at the same time (Figure 1.1). This was the real beginning of the practice of hairdressing as we now know it: that of having one’s hair done outside the home in a public place. Just that simple.

In no time at all, the situation in Paris had evolved into something very close to what we expect to find in any major capital today: there were roughly a half dozen stylists so high-profile that the addresses of their salons were listed in guides to Paris so that the well-heeled tourist would know where to turn in order to return home coiffed in the latest Parisian fashion. From Nicolas de Blégny’s insider’s address books of the early 1690s, we learn that the area where the luxury jewelers congregated, right around the Palais Royal, close by the Louvre, was also the place to head for haute coiffure, with three of the then trendiest establishments: the shops of Mademoiselle d’Angerville, Mademoiselle Le Brun, and the trendiest of them all, Mademoiselle Canilliat, stylist to the stars for decades.

FIGURE 1.1. This is the earliest depiction of a hair salon. One coiffeuse is busy designing an elaborate coiffure while on the wall behind her, on the table, and on the floor many of the accessories that enabled the first celebrity hairdressers to work their magic are displayed.

Already in January 1678, the first newspaper anywhere to provide in-depth coverage of the fashion scene, Le Mercure galant (Gallant Mercury), announced that Canilliat was the official coiffeuse for all the ballets held at court. (Louis XIV had a passion for ballet, so this was a high-profile assignment indeed, on the order of doing the hair of supermodels for photo shoots in Vogue.) Nearly twenty years later, Canilliat was still so much the celebrity coiffeuse that a character in a particularly fashion-conscious novel from 1696 was sent to her for a complete makeover. The other fashionable neighborhoods also had their boldface stylists: on the rue Saint-Honoré, a lady could entrust her tresses to Mademoiselle Poitiers, and no less a personnage than François Quentin, known professionally as La Vienne, one of the Sun King’s four premiers valets de chambre (first personal valets), maintained a shop in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. When the reign of celebrity stylists began, women dominated the profession, but men, following Champagne’s pathbreaking example, were chipping away at the old taboo.

Just as still remains true, different shops had different specialties: Versailles insiders went to Mademoiselle Cochois, whose salon was on the rue Aubry-le-Boucher near the Marais, for really big hair, elaborate mixes of fake and real, when invited to the grandest fêtes. Mademoiselle Borde and Mademoiselle Martin were all the rage in 1671, when fashionistas decided completely to abandon the traditional coiffe and to be styled only with their own hair, worn much curlier and a good deal shorter than ever before. This was an idea so wildly heretical that it’s now hard for us to imagine its impact; the fashion for bobbing in the 1920s was nothing compared with this moment when, for the first time in modern history, aristocratic women decided that shorter hair was more attractive than longer and that they would dare appear in public with nothing covering any part of the head.

On March 18, 1671, the Marquise de Sévigné, writing to describe the new look for her daughter who lived far from the Parisian scene, at first said that the women looked “completely naked,” like “little heads of cabbage,” and claimed that the supreme judge, the King, “had doubled over with laughter” at the very sight of it. Sévigné detailed the suffering required to look like a head of cabbage: women were sleeping “with a hundred rollers, which make them endure mortal agony all night long.” She dismissed the look’s proponents with what was surely the ultimate insult for her hyperelegant, hyperfeminine age, saying they were styled “en vrai fanfan,” just like a kid—much as the original devotees of Coco Chanel’s cropped hair and sporty silhouette were labeled “garçonnes,” tomboys or street urchins.

Even such extreme reactions did not stop many of the most fashionable ladies of the day from immediately adopting the radical new style. And such was the power of la mode that, only three days later, Sévigné was so “completely won over” that she told her daughter that “this hairstyle is made for your face,” and promis...