- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

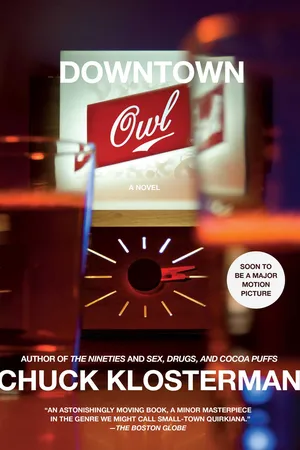

Now a major film! New York Times bestselling author and “one of America’s top cultural critics” (Entertainment Weekly) Chuck Klosterman’s debut novel brilliantly captures the charm and dread of small-town life.

Somewhere in rural North Dakota, there is a fictional town called Owl. They don’t have cable. They don’t really have pop culture, but they do have grain prices and alcoholism. People work hard and then they die. But that’s not nearly as awful as it sounds; in fact, sometimes it’s perfect. Mitch Hrlicka lives in Owl. He plays high school football and worries about his weirdness, or lack thereof. Julia Rabia just moved to Owl. A history teacher, she gets free booze and falls in love with a self-loathing bison farmer. Widower and local conversationalist Horace Jones has resided in Owl for seventy-three years. They all know each other completely, except that they’ve never met. But when a deadly blizzard—based on an actual storm that occurred in 1984—hits the area, their lives are derailed in unexpected and powerful ways. An unpretentious, darkly comedic story of how it feels to exist in a community where local mythology and violent reality are pretty much the same thing, Downtown Owl is “a satisfying character study and strikes a perfect balance between the funny and the profound” (Publishers Weekly).

Somewhere in rural North Dakota, there is a fictional town called Owl. They don’t have cable. They don’t really have pop culture, but they do have grain prices and alcoholism. People work hard and then they die. But that’s not nearly as awful as it sounds; in fact, sometimes it’s perfect. Mitch Hrlicka lives in Owl. He plays high school football and worries about his weirdness, or lack thereof. Julia Rabia just moved to Owl. A history teacher, she gets free booze and falls in love with a self-loathing bison farmer. Widower and local conversationalist Horace Jones has resided in Owl for seventy-three years. They all know each other completely, except that they’ve never met. But when a deadly blizzard—based on an actual storm that occurred in 1984—hits the area, their lives are derailed in unexpected and powerful ways. An unpretentious, darkly comedic story of how it feels to exist in a community where local mythology and violent reality are pretty much the same thing, Downtown Owl is “a satisfying character study and strikes a perfect balance between the funny and the profound” (Publishers Weekly).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

AUGUST 15, 1983

(Mitch)

When Mitch Hrlicka heard that his high school football coach had gotten another teenage girl pregnant, he was forty bushels beyond bamboozled. He could not understand what so many females saw in Mr. Laidlaw. He was inhumane, and also sarcastic. Whenever Mitch made the slightest mental error, Laidlaw would rhetorically scream, “Vanna? Vanna? Are you drowsy, Vanna? Wake up! You can sleep when you are dead, Vanna!” Mr. Laidlaw seemed unnaturally proud that he had nicknamed Mitch “Vanna White” last winter, solely based on one semifunny joke about how the surname “Hrlicka” needed more vowels. Mitch did not mind when other kids called him Vanna, because almost everyone he knew had a nickname; as far as he could tell, there was nothing remotely humiliating about being called “Vanna,” assuming everyone understood that the name had been assigned arbitrarily. It symbolized nothing. But Mitch hated when John Laidlaw called him “Vanna,” because Laidlaw assumed it was humiliating. And that, clearly, was his goal.

Christ, it was humid. When Mitch and his teenage associates had practiced that morning at 7:30 a.m., it was almost cool; the ground had been wet with dew and the clouds hovered fourteen feet off the ground. But now—eleven hours later—the sun was burning and falling like the Hindenburg. The air was damp wool. Mitch limped toward the practice field for the evening’s upcoming death session; he could already feel sweat forming on his back and above his nose and under his crotch. His quadriceps stored enough lactic acid to turn a triceratops into limestone. “God damn,” he thought. “Why do I want this?” In two days the team would begin practicing in full pads. It would feel like being wrapped in cellophane while hauling bricks in a backpack. “God damn,” he thought again. “This must be what it’s like to live in Africa.” Football was not designed for the summer, even if Herschel Walker believed otherwise.

When Mitch made it to the field, the other two Owl quarterbacks were already there, facing each other twelve yards apart, each standing next to a freshman. They were playing catch, but not directly; one QB would rifle the ball to the opposite freshman, who would (in theory) catch it and immediately flip it over to the second QB who was waiting at his side. The other quarterback would then throw the ball back to the other freshman, and the process would continue. This was how NFL quarterbacks warmed up on NFL sidelines. The process would have looked impressive to most objective onlookers, except for the fact that both freshman receivers dropped 30 percent of the passes that struck them in the hands. This detracted from the fake professionalism.

Mitch had no one to throw to, so he served as the holder while the kickers practiced field goals. This duty required him to crouch on one knee and remain motionless, which (of course) is not an ideal way to get one’s throwing arm loose and relaxed. Which (of course) did not really matter, since Coach Laidlaw did not view Mitch’s attempts at quarterbacking with any degree of seriousness. Mitch was not clutch. Nobody said this, but everybody knew. It was the biggest problem in his life.

At 7:01, John Laidlaw blew into a steel whistle and instructed everyone to bring it in. They did so posthaste.

“Okay,” Laidlaw began. “This is the situation. The situation is this: We will not waste any light tonight, because we have a beautiful evening with not many mosquitoes and a first-class opportunity to start implementing some of the offense. I realize this is only the fourth practice, but we’re already way behind on everything. It’s obvious that most of you didn’t put five goddamn minutes into thinking about football all goddamn summer, so now we’re all behind. And I don’t like being behind. I’ve never been a follower. I’m not that kind of person. Maybe you are, but I am not.

“Classes start in two weeks. Our first game is in three weeks. We need to have the entire offense ready by the day we begin classes, and we need to have all of the defensive sets memorized before we begin classes. And right now, I must be honest: I don’t even know who the hell is going to play for us. So this is the situation. The situation is this: Right now, everybody here is equally useless. This is going to be an important, crucial, important, critical, important two weeks for everyone here, and it’s going to be a real kick in the face to any of you who still want to be home watching The Price Is Right. And I know there’s going to be a lot of people in this town talking about a lot of bull crap that doesn’t have anything to do with football, and you’re going to hear about certain things that happened or didn’t happen or that supposedly happened or that supposedly allegedly didn’t happen to somebody that probably doesn’t even exist. These are what we call distractions. These distractions will come from all the people who don’t want you to think about Owl Lobo football. So if I hear anyone on this team perpetuating those kinds of bullshit stories, everyone is going to pay for those distractions. Everyone. Because we are here to think about Owl Lobo football. And if you are not thinking exclusively—exclusively—about Owl Lobo football, go home and turn on The Price Is Right. Try to win yourself a washing machine.”

It remains unclear why John Laidlaw carried such a specific, all-encompassing hatred for viewers of The Price Is Right. No one will ever know why this was. Almost as confusing was the explanation as to why Owl High School was nicknamed the Lobos, particularly since they had been the Owl Owls up until 1964. During the summer of ’64, the citizens of Owl suddenly concluded that being called the Owl Owls was somewhat embarrassing, urging the school board to change the nickname to something “less repetitive.” This proposal was deeply polarizing to much of the community. The motion didn’t pass until the third vote. And because most of the existing Owl High School athletic gear still featured its long-standing logo of a feathered wing, it was decided that the new nickname should remain ornithological. As such, the program was known as the Owl Eagles for all of the 1964–1965 school year. Contrary to community hopes, this change dramatically increased the degree to which its sports teams were mocked by opposing schools. During the especially oppressive summer of 1969, they decided to change the nickname again, this time becoming the Owl High Screaming Satans. (New uniforms were immediately purchased.) Two games into the ’69 football season, the local Lutheran and Methodist churches jointly petitioned the school board, arguing that the nickname “Satan” glorified the occult and needed to be changed on religious grounds; oddly (or perhaps predictably), the local Catholic church responded by aggressively supporting the new moniker, thereby initiating a bitter feud among the various congregations. (This was punctuated by a now infamous street fight that involved the punching of a horse.) When the Lutheran minister ultimately decreed that all Protestant athletes would have to quit all extracurricular activities if the name “Satan” remained in place, the school was forced to change nicknames midseason. Nobody knew how to handle this unprecedented turn of events. Eventually, one of the cheerleaders noticed that the existing satanic logo actually resembled an angry humanoid wolf, a realization that seemed brilliant at the time. (The cheerleader, Janelle Fluto, is now a lesbian living in Thunder Bay, Ontario.) The Screaming Satans subsequently became the Screaming Lobos, a name that was edited down to Lobos upon the recognition that wolves do not scream. This nickname still causes mild confusion, as strangers sometimes assume the existence of a mythological creature called the “Owl Lobo,” which would (indeed) be a terrifying (and potentially winged) carnivore hailing from western Mexico. But—nonetheless, and more importantly—there has not been any major community controversy since the late sixties. Things have been perfect ever since, if by “perfect” you mean “exactly the same.”

Mitch and the rest of the Lobos clapped their hands simultaneously and started to jog one lap around the practice field, ostensibly preparing to perform a variety of calisthenics while thinking exclusively about Owl Lobo football and not fantasizing about The Price Is Right. But such a goal was always impossible. It was still summer. As Mitch loped along the sidelines, his mind drifted to other subjects, most notably a) Gordon Kahl, b) the Georgetown Hoyas, c) how John Laidlaw managed to seduce and impregnate Tina McAndrew, and d) how awful it must feel to be John Laidlaw’s wife.

AUGUST 25, 1983

(Julia)

“You’re going to like it here,” said Walter Valentine. He said this from behind a nine-hundred-pound cherrywood desk, hands interlocked behind his head while his eyes looked toward the ceiling, focusing on nothing. “I have no doubt about that. I mean, it’s not like this is some kind of wonderland. This isn’t anyone’s destination city. It’s not Las Vegas. It’s not Monaco. It’s not like you’ll be phoning your gal pals every night and saying, ‘I’m living in Owl, North Dakota, and it’s a dream come true.’ But you will like it here. It’s a good place to live. The kids are great, in their own way. The people are friendly, by and large. You will be popular. You will be very, very popular.”

Julia did not know what most of those sentences meant.

“I will be popular,” she said, almost as if she was posing a question (but not quite).

“Oh, absolutely,” Valentine continued, now rifling through documents that did not appear particularly official. “I know that you are scheduled to teach seventh-grade history, eighth-grade geography, U.S. History, World History, and something else. Are you teaching Our State? I think you’re scheduled to teach Our State. Yes. Yes, you are. ‘Our State.’ But that’s just an unfancy name for North Dakota history, so that’s simple enough: Teddy Roosevelt, Angie Dickinson, lignite coal, that sort of thing. The Gordon Kahl incident, I suppose. Of course, the fact that you’re not from North Dakota might make that a tad trickier, but only during the first year. After that, history just repeats itself. But I suppose the first thing we should talk about is volleyball.”

“Pardon?”

“What do you know about volleyball?”

Julia had been in downtown Owl for less than forty-eight hours. The land here was so relentlessly flat; it was the flattest place she’d ever seen. She had driven from Madison, Wisconsin, in nine hours, easily packing her entire existence into the hatchback of a Honda Civic. There was only one apartment building in the entire town and it was on the edge of the city limits; it was a two-story four-plex, and the top two apartments were empty. She took the bigger one, which rented for fifty-five dollars a month. When she looked out her bedroom window, she could see for ten miles to the north. Maybe for twenty miles. Maybe she was seeing Manitoba. It was like the earth had been pounded with a rolling pin. The landlord told her that Owl was supposedly getting cable television services next spring, but he admitted some skepticism about the rumor; he had heard such rumors before.

Julia was now sitting in the office of the Owl High principal. He resumed looking at the ceiling, appreciating its flatness.

“I’ve never played volleyball,” Julia replied. “I don’t know the rules. I don’t even know how the players keep score of the volley balling.”

“Oh. Oh. Well, that’s unfortunate,” Valentine said. “No worries, but that’s too bad. I only ask because it looks like we’re going to have to add volleyball to the extracurricular schedule in two years, or maybe even as soon as next year. It’s one of those idiotic Title IX situations—apparently, we can’t offer three boys’ sports unless we offer three girls’ sports. So now we have to figure out who in the hell is going to coach girls’ volleyball, which is proving to be damn near impossible. Are you sure that isn’t something you might eventually be interested in? Just as a thought? You would be paid an additional three hundred dollars per season. You’d have a full year to get familiar with the sport. We’d pay for any books on the subject you might need. I’m sure there are some wonderful books out there on the nature of volleyball.”

“I really, really cannot coach volleyball,” Julia said. “I’m not coordinated.”

“Oh. Oh! Okay, no problem. I just thought I’d ask.” Mr. Valentine looked at her for a few moments before his pupils returned to the ceiling. “Obviously, it would be appreciated if you thought about it, but—ultimately—volleyball doesn’t matter. We just want you to do all the things that you do, whatever those things may be. I’m sure you bring a lot to the table. Do you have any questions for me?”

Julia had 140,000 questions. She asked only one.

“What’s it like to live here?”

This was not supposed to sound flip, but that’s how it came out. Julia always came across as cocky whenever she felt nervous.

“It’s like living anywhere, I suppose.” Valentine unlocked his fingers and crossed his arms, glancing momentarily at Julia’s face. He then proceeded to stare at the mallard duck that was painted on his coffee cup, half filled with cherry Kool-Aid. “Owl’s population used to be around twelve hundred during the height of the 1970s, but now it’s more like eight hundred. Maybe eight fifty. I don’t know where all the people went. It’s a down town, Owl. We still have a decent grocery store, which is important, but—these days—it seems like a lot of folks will drive to Jamestown, or even all the way to Valley City, just to do their food shopping. Americans are crazy. There’s a hardware store, but I wonder how much longer that will last. We have a first-rate Chevrolet dealership. We have two gas stations. We have seven bars, although you can hardly count the Oasis Wheel. You probably don’t want to spend your nights at the Oasis Wheel, unless you’re not the kind of woman I think you are. Heh! And you’ve probably heard that the movie theater is going to close, and I’m afraid that’s true: It is closing. But the bowling alley is thriving. It’s probably the best bowling alley in the region. I honestly believe that.”

By chance, Julia did enjoy bowling. However, when the most positive detail about your new home is that the bowling alley is thriving, you have to like bowling a lot in order to stave off depression. And—right now, in the middle of this conversation—Julia was more depressed than she had ever been in her entire twenty-three-year existence. As she sat in Walter Valentine’s office, she felt herself wanting to take a nap on the floor. But she (of course) did not do this; she just looked at him, nodding and half smiling. She could always sleep later, after she finished crying.

“The thing that you have to realize about a place like Owl is that everyone is aware of all the same things. There’s a lot of shared knowledge,” Valentine said. He was now leaning forward in his chair, looking at Julia and casually pointing at her chest with both his index fingers. “Take this year’s senior class, for example. There are twenty-six kids in that class. Fifteen of them started kindergarten together. That means that a lot of those students have sat next to each other—in just about every single class—for thirteen straight years. They’ve shared every single experience. You said you grew up in Milwaukee, correct?”

“Yes.”

“How big was your graduating class?”

“Oh, man. I have no idea,” Julia said. “Around seven hundred, I think. It was a normal public school.”

“Exactly. Normal. But your normal class was almost as big as our whole town. And the thing is, when those twenty-six seniors graduate, the majority will go to college, at least for two years. But almost all the farm kids—or at least all the farm boys—inevitably come back here when they’re done with school, and they start farming with their fathers. In other words, the same kids who spent thirteen years in class with each other start going to the same bars and they bowl together and they go to the same church and pretty much live an adult version of their high school life. You know, people always say that nothing changes in a small town, but—whenever they say that—they usually mean that nothing changes figuratively. The truth is that nothing changes literally: It’s always all the same people, doing all the same things.”

Upon hearing this description, the one singular phrase that went through Julia’s head was “Jesus fucking Christ.” However, those were not the words that she spoke.

“Wow,” she said. “That sounds kind of … unmodern.”

“It is,” Valentine said. Then he chuckled. Then he re-interlocked his fingers behind his skull and refocused his gaze on the ceiling. “Except that it’s not. It’s actually not abnormal at all. Look: I came here as a math teacher twenty years ago, and I thought I would be bored out of my trousers. I had grown up in Minot and I went to college in Grand Forks, so I considered myself urban. I always imagined I’d end up in Minneapolis, or even maybe Chicago; I have a friend from college who lives just outside of Chicago, so I’ve eaten in restaurants in that area and I have an understanding of that life. But once I really settled in Owl, I never tried to leave. I mean … sure, sometimes you think, ‘Hey, maybe there’s something else out there.’ But there really isn’t. This is what being alive feels like, you know? The place doesn’t matter. You just live.”

Julia could feel hydrochloric acid inside her tear ducts. There was an especially fuzzy tennis ball in her esophagus, and she wanted to be high.

But she remained cool.

Julia told Mr. Valentine she was extremely excited to be working at Owl High, and she thanked him for giving her the opportunity to start a career in teaching, which she claimed was her lifelong dream. “Everybody only has one first job,” he said in response. “No matter what you do in life, you’ll always remember your first job. So welcome aboard and good luck, although you won’t need it. You’ll be extremely popular here. And if you change your mind about that excellent volleyball opportunity, do not hesitate to call. Keep me in the loop. I’m always here, obviously.”

Julia exited Valentine’s office and walked toward the school’s main entrance, faster and more violent with every step. She was virtually running when she got to the door and sprinted to her ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Description

- Author Bio

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter 1: August 15, 1983

- Chapter 2: August 25, 1983

- Chapter 3: August 28, 1983

- Chapter 4: August 29, 1983

- Chapter 5: September 2, 1983

- Chapter 6: September 8, 1983

- Chapter 7: September 9, 1983

- Chapter 8: September 26, 1983

- Chapter 9: October 12, 1983

- Chapter 10: October 17, 1983

- Chapter 11: October 22, 1983

- Chapter 12: October 26, 1983

- Chapter 13: October 29, 1983

- Chapter 14: November 1, 1983

- Chapter 15: November 8, 1983

- Chapter 16: November 21, 1983

- Chapter 17: November 22, 1983

- Chapter 18: November 23, 1983

- Chapter 19: November 24, 1983

- Chapter 20: November 25, 1983

- Chapter 21: December 9, 1983

- Chapter 22: December 21, 1983

- Chapter 23: December 22, 1983

- Chapter 24: December 28, 1983

- Chapter 25: New Year’s day, 1984

- Chapter 26: January 5, 1984

- Chapter 27: January 7, 1984

- Chapter 28: January 11, 1984

- Chapter 29: January 17, 1984

- Chapter 30: January 20, 1984

- Chapter 31: January 23, 1984

- Chapter 32: January 26, 1984

- Chapter 33: January 29, 1984

- Chapter 34: January 31, 1984

- Chapter 35: February 3, 1984

- Chapter 36: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 37: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 38: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 39: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 40: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 41: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 42: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 43: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 44: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 45: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 46: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 47: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 48: February 4, 1984

- Chapter 49: February 4, 1984

- Acknowledgments

- ‘But What If We’re Wrong: Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past’ Excerpt

- 'Eating the Dinosaur' Teaser

- Footnotes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Downtown Owl by Chuck Klosterman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Literatur Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.