![]() David Lehman was born in New York City in 1948. He is the author of seven books of poems, most recently When a Woman Loves a Man (Scribner, 2005). Among his nonfiction books are The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets (Anchor, 1999) and The Perfect Murder (Michigan, 2000). He edited Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present, which appeared from Scribner in 2003. He teaches writing and literature in the graduate writing program of the New School in New York City and offers an undergraduate course each fall on “Great Poems” at NYU. He edited the new edition of The Oxford Book of American Poetry, a one-volume comprehensive anthology of poems from Anne Bradstreet to the present. Lehman has collaborated with James Cummins on a book of sestinas, Jim and Dave Defeat the Masked Man (Soft Skull), and with Judith Hall on a “p’lem,” or “play poem,” combining words and images, Poetry Forum (Bayeux Arts). He initiated the Best American Poetry series in 1988 and received a Guggenheim Fellowship a year later. He lives in New York City and in Ithaca, New York.

David Lehman was born in New York City in 1948. He is the author of seven books of poems, most recently When a Woman Loves a Man (Scribner, 2005). Among his nonfiction books are The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets (Anchor, 1999) and The Perfect Murder (Michigan, 2000). He edited Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present, which appeared from Scribner in 2003. He teaches writing and literature in the graduate writing program of the New School in New York City and offers an undergraduate course each fall on “Great Poems” at NYU. He edited the new edition of The Oxford Book of American Poetry, a one-volume comprehensive anthology of poems from Anne Bradstreet to the present. Lehman has collaborated with James Cummins on a book of sestinas, Jim and Dave Defeat the Masked Man (Soft Skull), and with Judith Hall on a “p’lem,” or “play poem,” combining words and images, Poetry Forum (Bayeux Arts). He initiated the Best American Poetry series in 1988 and received a Guggenheim Fellowship a year later. He lives in New York City and in Ithaca, New York.![]()

FOREWORD

by David Lehman

A parody, even a merciless one, is not necessarily an act of disrespect. Far from it. Poets parody other poets for the same reason they write poems in imitation (or opposition): as a way of engaging with a distinctive manner or voice. A really worthy parody is implicitly an act of homage.

Some great poets invite parody. Wordsworth’s “Resolution and Independence” prompted Lewis Carroll to pen “The White Knight’s Song” in Through the Looking Glass. In a wonderful poem, J. K. Stephen alludes to the sestet of a famous Wordsworth sonnet (“The world is too much with us”) to dramatize the wide discrepancy between Wordsworth at his best and worst. “At certain times / Forth from the heart of thy melodious rhymes, / The form and pressure of high thoughts will burst,” Stephen writes. “At other times—good Lord! I’d rather be / Quite unacquainted with the ABC / Than write such hopeless rubbish as thy worst.”

Among the moderns, T. S. Eliot reliably triggers off the parodist. Wendy Cope brilliantly reduced The Waste Land to five limericks (“The Thames runs, bones rattle, rats creep; / Tiresias fancies a peep—/ A typist is laid, / A record is played—/Wei la la. After this it gets deep”) while Eliot’s late sententious manner stands behind Henry Reed’s “Chard Whitlow” with its throat-clearing assertions (“As we get older we do not get any younger”). In a recent (2006) episode of The Simpsons on television, Lisa Simpson assembles a poem out of torn-up fragments, and attributes it to Moe the bartender. The title: “Howling at a Concrete Moon.” The inspiration: The Waste Land. The cigar-chewing editor of American Poetry Perspectives barks into the phone, “Genius. Pay him nothing and put him on the cover.”

Undoubtedly the most parodied of all poems is Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” which has long served graduation speakers and Polonius-wannabes as a touchstone. Arnold turned forty-five in 1867, the year the poem first appeared in print. Here it is: DOVER BEACH

The sea is calm to-night.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits;—on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanch’d land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

The greatness of this poem lies in the way it transforms the painting of a scene into a vision of “eternal sadness” and imminent danger. Moonlight and the English Channel contemplated from atop the white cliffs of Dover by a man and woman in love would seem a moment for high romance, and a reaffirmation of vows as a prelude to sensual pleasure. But “Dover Beach,” while remaining a love poem, is not about the couple so much as it is about a crisis in faith and a foreboding of dreadful things to come. It communicates the anxiety of an age in which scientific hypotheses, such as Darwin’s theory of evolution, combined with philosophical skepticism to throw into doubt the comforting belief in an all-knowing and presumably benevolent deity. The magnificent closing peroration, as spoken by the poet to his beloved, has the quality of a prophecy darkly fulfilled. Genocidal violence, perpetrated by “ignorant armies,” marked the last century, and it is undeniable that we today face a continuing crisis in faith and confidence. Seldom have our chief institutions of church and state seemed as vulnerable as they do today with, on the one side, a citizenry that seems alienated to the extent that it is educated, and on the other side, enemies as implacable and intolerant as they are medieval and reactionary.

Though traditional in its means, “Dover Beach” is, in its spirit and its burden of sense, a brutally modern poem, and among the first to be thus designated. “Arnold showed an awareness of the emotional conditions of modern life which far exceeds that of any other poet of his time,” Lionel Trilling observed. “He spoke with great explicitness and directness of the alienation, isolation, and excess of consciousness leading to doubt which are, as so much of later literature testifies, the lot of modern man.” And Trilling goes on to note that in “Dover Beach” in particular the diction is perfect and the verse moves “in a delicate crescendo of lyricism” to the “great grim simile” that lends the poem’s conclusion its desperation and its pathos.

While perfect for the right occasion, a recitation of the poem is, because of its solemnity, absurd in most circumstances, as when, in the 2001 movie The Anniversary Party, the Kevin Kline character recites the closing lines from memory in lieu of an expected lighthearted toast, and the faces of the other characters change from pleasure to confusion and alarm. Inspired responses to “Dover Beach” spring to mind. In “The Dover Bitch,” Anthony Hecht presents the situation of Arnold’s poem from the woman’s point of view. She rather resents being treated “as a sort of mournful cosmic last resort,” brought all the way from London for a honeymoon and receiving a sermon instead of an embrace. Tom Clark lampoons “Dover Beach” more farcically. His poem begins as Arnold’s does, but where in the third line of the original “the French coast” gleams in the distance, in Clark’s poem light syrup drips on “the French toast,” and the poem continues in the spirit of “crashing ignorance.” A third example is John Brehm’s “Sea of Faith,” which Robert Bly selected for the 1999 edition of The Best American Poetry. Here a college student wonders whether the body of water named in the poem’s title exists in geographical fact. The student’s ignorance seems to confirm Arnold’s gloomy vision, but it also spurs the instructor to a more generous response. After all, who has not felt the unspoken wish for an allegorical sea in which one can swim and reemerge “able to believe in everything, faithful / and unafraid to ask even the simplest of questions, / happy to have them simply answered”?

Poets like to parody “Dover Beach” because the poem takes itself so very seriously and because Arnold’s wording sticks in the mind. But not everyone agrees on what lesson we should draw from this case. The poet Edward Dorn, author of Gunslinger and other estimable works, called “Dover Beach” the “greatest single poem ever written in the English language.” What amazed Dorn was that it should be Arnold who wrote it. According to Dorn, Arnold “wrote volume after volume of lousy, awful poetry.” The anomaly “proves that you should never give up,” Dorn added. If Arnold with his “pedestrian mind” could write “Dover Beach,” then “anybody could do it.”

I have dwelled on “Dover Beach” as an object of irreverence not only because the parodic impulse, which informs so many contemporary poems (including some in this volume), is misunderstood and sometimes unfairly derogated, but also because of a superb counterexample that came to my attention this year. In his novel Saturday (2005), Ian McEwan makes earnest use of “Dover Beach” as a rich, unironic emblem of the values of Western Civilization. It is not the only such emblem in the book. There are Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, to which the book’s neurosurgeon hero listens when operating, and there is the surgeon’s knife, the antithesis of the thug’s switchblade. But a reading aloud of “Dover Beach” in the most extreme of circumstances marks the turning point in the plot of this novel whose subject is terror and terrorism.

Set in London on a day of massive antiwar demonstrations, Saturday centers on a car accident that pits Henry, the surgeon, against Baxter, a local crime boss. Henry gets the better of Baxter in the confrontation, and in retaliation the gangster and a henchman mount an assault on the surgeon and his family in their posh London home. Baxter systematically humiliates Henry’s grown daughter, an aspiring poet, forcing her to strip off all her clothing in front of her horrified parents, brother, and grandfather. But the young woman’s just-published first book of poems, lying on the coffee table, catches Baxter’s eye, and he commands her to read from it. She opens the book but recites “Dover Beach” from memory instead—with startling consequences. The transformation of the gangster is abrupt and total. In a flash he goes “from lord of terror to amazed admirer,” a state in which it becomes possible for the family to overpower him. Thus does poetry, in effect, disarm the brute and lead to the family’s salvation.

With the restoration of safety and order, McEwan allows himself a little joke at the expense of both Matthew Arnold and his own protagonist. The surgeon tells his daughter of her choice of poem, “I didn’t think it was one of your best.” The joke, a good one, reminds us of the poem’s complicated cultural status: revered, iconic, but also mildly desecrated, like a public statue exposed to pigeons and graffiti artists. But McEwan has already made his more significant point. Just as the instructor in John Brehm’s poem can find himself yearning for an escape to an allegorical Sea of Faith, so I believe we all secretly think of poetry, this art that we love unreasonably, as somehow antidotal to malice and vice, cruelty and wrath. We know it isn’t so, and yet we persist in writing poems that shoulder the burden of conscience. In The Best American Poetry 2007 you will find poems in a variety of tonal registers—by such poets as Denise Duhamel, Robert Hass, Frederick Seidel, Brian Turner, and Joe Wenderoth—that address subjects ranging from “Bush’s War” to the “language police,” from the decapitation of an American citizen in Iraq to the overthrow of the shah of Iran.

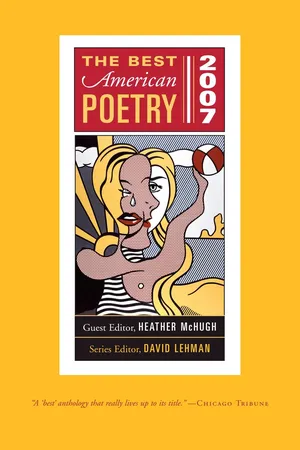

For such a poem to gain entry into this volume, it had to meet exceptionally high criteria. Heather McHugh, the editor of The Best American Poetry 2007, sets store, she told an interviewer, by wordplay, puns, rhymes, the hidden life of words, “the is in the wish, the or in the word. No word-fun should be left undone.” McHugh has spoken with cutting eloquence against glib and simplistic poems by well-meaning citizens: “So much contemporary American poetry is deadly serious, reeking of the NPR virtues: back-to-the-earth soup eaten fresh from the woodstove, all its spices listed, then some admirable thoughts to put to paper when we get home. Hey, Romanticism isn’t dead—it’s simply being turned to public pap. Against that tedium, a little unholiness comes as a big relief—the skeptic skeleton, the romping rump.” But it should also be noted that McHugh herself, for all the wit and wordplay in her poems, has written a poem that I would not hesitate to characterize as powerful, earnest, and political: “What He Said” (1994), which culminates in a definition of poetry as what the heretical philosopher Giordano Bruno, when burned at the stake, “thought, but did not say,” with an iron mask placed on his face, as the flames consumed him.

In his poem “My Heart,” Frank O’Hara wrote, “I’m not going to cry all the time / nor shall I laugh all the time, / I don’t prefer one ‘strain’ to another.” By temperament and inclination I favor both kinds of poems—the kind that celebrates and the kind that criticizes; the kind that affirms a vow and the kind that makes merry; the poem of high seriousness that would save the world and the poem of high hilarity that would mock the pretensions of saviors. I believe, with Wordsworth, that the poet’s first obligation is always to give pleasure, and I would argue, too, that a poem exhibiting the comic spirit can be every bit as serious as a poem devoid of laughter. The poems McHugh gathers in this volume are unafraid to confront the world in its contradictory guises and moods. The unlikely cast of characters includes authentic geniuses from far-flung places: Catullus, Leonardo, Voltaire, Kant, the lyricist Lorenz Hart. There are sonnets and prose poems, a set of haiku and a country-western song, a double abecedarian and a lover’s quarrel with a famous Frost poem. And there are poems that take a mischievous delight in the English language as an organic thing, a living system, full of puns that reveal truths just as jokes and errors served Freud: as ways the mind inadvertently discloses itself Some of these poems are very funny, and need no further justification. “The human race has one really effective weapon, and that is laughter,” Mark Twain remarked.

There is a dangerous if common misconception that a political poem, or any poem that aspires to move the hearts and minds of men and women, must be reducible to a paraphrase the length of a slogan, be it that “war is hell” or that “hypocrisy is rampant” or that “it is folly to launch a major invasion without a postwar strategy in place.” For such sentiments, an editorial or a letter to the editor would serve as the proper vehicle. We want something more complicated and more lasting from poetry. An anecdote from the biography of Oscar Hammerstein II, who succeeded Lorenz Hart as Richard Rodgers’s lyricist, may help here. When Stephen Sondheim, then in high school, appealed for advice to Hammerstein, his mentor, the latter criticized a song the young man had written: “This doesn’t say anything.” Sondheim recalls answering defensively, “What does ‘Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’ say?” With a firmness Sondheim would not forget, Hammerstein responded, “Oh, it says a lot.”

The parodist in each of us will continue to enjoy a secret laugh at “Dover Beach.” But we also know that people who live in newspapers die for want of what there is in Arnold’s poem and in great poetry in general. Real poetry sustains us. György Faludy, the Hungarian poet and Resistance hero, died on September 1, 2006, sixty-seven years to the day after the Nazis invaded Poland. Faludy attacked Hitler in a poem but managed to escape to the United States and served in the American army during World War II. He wasn’t nearly so fortunate when he returned to Hungary following the war. For three years, from 1950 to 1953, the Soviets imprisoned Faludy in Recsk, Hungary’s Stalinist concentration camp. He endured terrible hardships, but even without a pen he wrote, using the bristle of a broom to inscribe his verses in blood on toilet paper. He had to write. Poetry was keeping him alive. He recited his poems and made fellow prisoners memorize them. The imagination created hope, and the heart committed its lines to memory. When Faludy called his prose book about the years in the camp “My Happy Days in Hell,” it was with obvious irony, but it also hinted at his faith. He had listened to the melancholy, long withdrawing roar of the sea, survived the shock, and outlived the Soviet occupation just as his beloved Danube River had done.

![]() Heather McHugh was born in San Diego, California, in 1948. She was raised in Virginia and educated at Harvard University. She is the Milliman Distinguished Writer-in-Residence at the University of Washington in Seattle and has held visiting appointments at the University of California at Berkeley and at the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. She regularly visits the low-residency creative writing program at Warren Wilson College near Asheville, North Carolina. Her books of poetry include Eyeshot (Wesleyan University Press, 2003), The Father of the Predicaments (Wesleyan, 1999), Hinge & Sign: Poems 1968-1993 (Wesleyan, 1994), and Dangers (Houghton Mifflin, 1977). Her collection of literary essays is entitled Broken English: Poetry and Partiality (1993). Glottal Stop: 101 Poems by Paul Celan, which she translated in collaboration with her husband, Nikolai Popov, was published in the fall of 2000. Her translation of the poems of Jean Follain was published by Princeton in 1981, and her version of Euripides’ Cyclops by Oxford University Press in 2003. She has received fellowships and grants from the Lila Wallace Foundation, United States Artists, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and in 1999 was named a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. She was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2000.

Heather McHugh was born in San Diego, California, in 1948. She was raised in Virginia and educated at Harvard University. She is the Milliman Distinguished Writer-in-Residence at the University of Washington in Seattle and has held visiting appointments at the University of California at Berkeley and at the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. She regularly visits the low-residency creative writing program at Warren Wilson College near Asheville, North Carolina. Her books of poetry include Eyeshot (Wesleyan University Press, 2003), The Father of the Predicaments (Wesleyan, 1999), Hinge & Sign: Poems 1968-1993 (Wesleyan, 1994), and Dangers (Houghton Mifflin, 1977). Her collection of literary essays is entitled Broken English: Poetry and Partiality (1993). Glottal Stop: 101 Poems by Paul Celan, which she translated in collaboration with her husband, Nikolai Popov, was published in the fall of 2000. Her translation of the poems of Jean Follain was published by Princeton in 1981, and her version of Euripides’ Cyclops by Oxford University Press in 2003. She has received fellowships and grants from the Lila Wallace Foundation, United States Artists, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and in 1999 was named a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. She was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2000.![]()

INTRODUCTION

by Heather...