- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

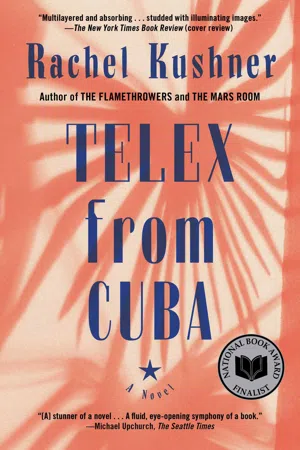

A National Book Award Finalist for Fiction

The debut novel by New York Times bestselling author Rachel Kushner, called “shimmering” (The New Yorker), “multilayered and absorbing” (The New York Times Book Review), and “gorgeously written” (Kirkus Reviews).

Young Everly Lederer and K.C. Stites come of age in pre-revolutionary Cuba, where the American expatriates tend their own fiefdom—three hundred thousand acres of United Fruit Company sugarcane that surround their gated enclave under the shadow of the Batista dictatorship. If the rural tropics are a child's dreamworld, Everly and K.C. nevertheless have keen eyes for the indulgences and betrayals of the grown-ups around them—the mordant drinking and illicit loves, the race hierarchies and violence.

In Havana, a thousand kilometers and a world away from the American colony, a cabaret dancer meets a French agitator named Christian de La Mazière, whose seductive demeanor can’t mask his shameful past. Together they become enmeshed in the brewing revolutionary underground and the political upheaval that will soon transform the island. When Fidel Castro and Raúl Castro lead a revolt from the mountains above the cane plantation, torching the sugar and kidnapping a boat full of "yanqui" revelers, K.C. and Everly begin to discover the brutality that keeps the colony and its corporate imperialism humming. Though their parents remain blissfully untouched by the forces of history, the children hear the whispers of what is to come.

Kushner’s first novel is a tour de force, haunting and compelling, with the urgency of a telex from a forgotten time and place.

The debut novel by New York Times bestselling author Rachel Kushner, called “shimmering” (The New Yorker), “multilayered and absorbing” (The New York Times Book Review), and “gorgeously written” (Kirkus Reviews).

Young Everly Lederer and K.C. Stites come of age in pre-revolutionary Cuba, where the American expatriates tend their own fiefdom—three hundred thousand acres of United Fruit Company sugarcane that surround their gated enclave under the shadow of the Batista dictatorship. If the rural tropics are a child's dreamworld, Everly and K.C. nevertheless have keen eyes for the indulgences and betrayals of the grown-ups around them—the mordant drinking and illicit loves, the race hierarchies and violence.

In Havana, a thousand kilometers and a world away from the American colony, a cabaret dancer meets a French agitator named Christian de La Mazière, whose seductive demeanor can’t mask his shameful past. Together they become enmeshed in the brewing revolutionary underground and the political upheaval that will soon transform the island. When Fidel Castro and Raúl Castro lead a revolt from the mountains above the cane plantation, torching the sugar and kidnapping a boat full of "yanqui" revelers, K.C. and Everly begin to discover the brutality that keeps the colony and its corporate imperialism humming. Though their parents remain blissfully untouched by the forces of history, the children hear the whispers of what is to come.

Kushner’s first novel is a tour de force, haunting and compelling, with the urgency of a telex from a forgotten time and place.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

1

January 1958

It was the first thing I saw when I opened my eyes that morning. An orange rectangle, the color of hot lava, hovering on the wall of my bedroom. It was from the light, which was streaming through the window in a dusty ray, playing on the wall like a slow and quiet movie. Just this strange, orange light. I was sure that at any moment it would vanish, like when a rainbow appears and immediately starts to fade, and you look where you saw it moments before and it’s gone, just the faintest color, and even that faint color you might be imagining from the memory of what you just saw.

I went to the window and looked out. The sky was a hazy violet, like the color of the delicate skin under Mother’s eyes, half circles that went dark when she was tired. The sun was a blurred, dark red orb. You could look directly at it through the haze, like a jewel under layers of tissue. I figured we were in for some kind of curious weather. In eastern Cuba, there were mornings I’d wake up and sense immediately that the weather had radically turned. I could see the bay from my window, and if a tropical storm was approaching, the sunrise would spread ribbons of light into the dense clouds piling up on the water’s horizon, turning them rose-colored like they were glowing from inside. I loved the feeling of waking up to some drastic change, knowing that when I went downstairs the servants would be rushing around, taking the patio furniture inside and nailing boards over the windows, the air outside warm and gusting, the first giant wave surging in a glassy, green wall and drenching the embankment just beyond our garden. If a storm had already approached, I’d wake up to rain pouring down over the house, my room so dark I had to turn on the bedside lamp just to read the clock. Change was exciting to me, and when I woke up that morning and saw a rectangle of orange light, bright as embers, on my bedroom wall, it seemed like something special was about to happen.

It was early, and Mother and Daddy were still asleep. My brother, Del, had been gone for three weeks at that point, ever since we’d returned from our Christmas vacation in Havana. Daddy didn’t talk about it openly, but I knew Del was up in the mountains with Raúl’s column. I’d never been much for the pool hall in Mayarí, but I started hanging around down there after he disappeared. In Preston it was difficult to get information about the rebels. The Cubans all knew what was going on, but they kept quiet around Americans. The company was putting a lot of pressure on workers to stay away from anyone involved with the rebels. Who’s going to talk to the boss’s thirteen-year-old son? Down in Mayarí, people got drunk and opened their mouths. The week before, an old campesino grabbed me by the shoulder. He put his face up to mine, so close I could smell his rummy breath. He said something about Del. He said he was still young, but that he would be one of the great ones. A liberator of the people. Like Bolívar.

I could hear Annie making breakfast, opening and shutting drawers. I put on my slippers and went downstairs. It was so dark in the kitchen I could barely see. Annie had latched all the windows and closed the jalousies. I asked why she didn’t open the shutters or put on a light.

Servants have their funny ways—superstitions—and you never know what they’re up to. Annie didn’t like to go out at dusk. If Mother insisted she run some errand, Annie put a scarf over her mouth. She said evil spirits tried to fly into women’s mouths at dusk. Annie and our laundress, Darcina, both listened to this cockeyed faith healer Clavelito on radio CMQ. Darcina sometimes cried at night. She said she missed sleeping in a bed with her children. Mother bought her a portable to keep her company and ended up buying one for Annie as well, just to be fair. Mother was big on fairness. Clavelito told folks to set a glass of water on top of the radio, something about his voice blessing the water, and Annie and Darcina both did.

Annie said she’d closed the shutters on account of the air. There was an awful haze, and it was tickling her nose and making her hoarse. She said it must have been those guajiros burning their trash again. Annie didn’t like the campesinos. She was a house servant, and that’s a different class.

I sat down in the kitchen with the new issue of Unifruitco, our company magazine. It came out bimonthly, meaning the news was always a bit stale. This was January 1958, and on the front page was a photo of my brother and Phillip Mackey posing with a swordfish they’d caught in Nipe Bay, back in October. They’d won first prize in the fall fishing tournament. It was strange to see that photograph, now that both of them were gone and my brother no longer cared about things such as fishing tournaments. On the next page was Daddy with Batista and Ambassador Smith on our yacht the Mollie and Me. I flipped through the pages while Annie made pastry dough. She cut the dough into circles, put cheese and guava paste into the little circles, folded them over into half moons, and spread them on a baking sheet. Annie’s pastelitos de guayaba, warm from the oven, were the most delicious things in the world. Some of the Americans in Preston didn’t allow their servants to cook native. Mother was considerably more open-minded about these things, and she absolutely loved some of the Cuban dishes. Mother didn’t cook. She made lists for Annie. Annie would take a huge red snapper and stuff it with potatoes, olives, and celery, then marinate it in butter and lime juice and bake it in the oven. That was my favorite. Six months earlier, in the summer of ’57, when I turned thirteen, Annie said that because I was a young man and would be grown up before she knew it, she wanted to make me a rum cake for my wedding. Thirteen-year-old boys are not exactly thinking about marriage. Sure I’d fooled around with girls, but there wasn’t any formal courtship going on. A rum cake will keep for ten or fifteen years, and Annie figured that was enough time for me to grow up and find a wife. She had the guys at the company machine shop make a five-tier tin just for that cake. The tin was painted white, with Kimball C. Stites handpainted on top, and handles on the sides for pulling out the cake layers. I don’t know what happened to the cake or the tin with my name on it. Lost in the rush of leaving, like so many of our things.

Annie was putting her pastelitos in the oven when I heard Daddy’s footsteps pounding down the stairs, and Mother calling after him, “Malcolm! Malcolm, please in God’s name be careful!”

I ran into the foyer and met Daddy at the bottom of the stairs. He didn’t look at me, just charged past like I was invisible, opened the front door, and took the veranda steps two at a time. I followed him, running down the garden path in my pajamas. He went around to the servants’ quarters behind the house and pounded on Hilton Hardy’s door. Hilton was Daddy’s chauffeur.

“Hilton! Wake up!” He pounded on the door again. That was when I noticed Daddy still had on his rumpled pajama shirt underneath his suit jacket.

“Mr. Stites, Mr. Hardy visiting his people in Cayo Mambí,” Annie called from the window of the butler’s pantry, her voice muffled through the shut jalousies. “He got permission from Mrs. Stites.”

Daddy swore out loud and rushed to the garage where Hilton kept the company limousine, a shiny black Buick. We had two of them—Dynaflows, with the chromed, oval-shaped ventiports along the front fenders. Daddy opened the garage doors and got in the car, but he didn’t start it. He got back out and shouted up to the house, “Annie! Where does Hilton keep the keys to this goddamn thing?”

“On a hook in there, Mr. Stites. Mr. Hardy have all the keys on hooks,” she called back.

Daddy found the keys, revved the Buick, and backed it out of the garage. I watched from the path and didn’t dare ask what was happening. He roared down the driveway, wheels spitting up gravel, and took a right on La Avenida.

That was the first time in my life I ever saw Daddy behind the wheel of his own car. He always had a driver. Daddy wore a white duck suit every day, perfectly creased, the bejesus starched out of it. A white shirt, white tie, and his panama hat. Every afternoon Hilton Hardy took him on his rounds in the Buick limousine. At each stop a secretary served Daddy a two-cent demitasse of Cuban coffee. They knew exactly what time he was coming and just how he liked his demitasse: a thimble-sized shot, no sugar. A “demi demi,” he used to say. According to him, he never got sick because his stomach was coated with the stuff. Daddy was old-fashioned. He had his habits and he took his time. He was not a man who rushed.

* * *

I remember how the cane cutters lived: in one-room shacks called bohios. Dirt floors, a pot in the middle of the room, no windows, no plumbing, no electricity. The only light was what came through the open doorway and filtered into the cracks between the thatched palm walls. They slept in hammacas. They were squatters, but the company tolerated it because they had to live somewhere during the harvest. The rest of the year—the dead time, they called it—they were desolajos. I don’t know what they did. Wandered the countryside looking for work and food, I guess. In the shantytown where the cane cutters lived—it’s called a batey—there were naked children running everywhere. None of those people had shoes, and their feet had hard shells of calloused skin around them. They cooked their meals outdoors, on mangrove charcoal. Got their water from a spigot at the edge of the cane fields. They had to carry their water in hand buckets, but the company let them take as much as they wanted. It was certainly a better deal than the mine workers got over in Nicaro. Those people were employees of the U.S. government, and they had to get their water from the river—the Levisa River—where they dumped the tailings from the nickel mine. The Nicaro workers drank from the river, bathed in the river, washed their clothes in the river. If you wash your bike in the Levisa River after it rains, it gets shiny clean. That’s a Cuban thing. I don’t know why, but it really works. After it rained, everybody was down there, boys and grown men wading into the river in their underwear, washing cars and bicycles.

The American kids on La Avenida weren’t supposed to go beyond the gates of Preston, down to the cane cutters’ batey. I think it was a company policy. Inside the gates was okay. Beyond the gates, you were looking for trouble. But Hatch Allain’s son Curtis Junior and I went down there all the time. We were boys, and curious. We sneaked into native dances. Curtis liked Cuban girls. That was a thing—some of the American kids only dated Cubans. Phillip Mackey and Everly Lederer’s sister Stevie from over in Nicaro were both like that, and they both got shipped off to boarding school in the States. Though in Phillip’s case it wasn’t just girls but the trouble he and my brother got into together, helping the rebels. The Cuban girls never gave poor Curtis the chance to get in any trouble. He was dirty and his ears stuck out, and the girls just didn’t like him. I tried to tell him that you have to be a little aloof, a little bit take-it-or-leave-it, even if it isn’t how you really feel, but Curtis just didn’t get it.

It was Daddy’s idea to give the cane cutters plots of land so they could feed themselves, grow yucca and sweet potatoes. He believed in self-sufficiency. He brought over Rev. Crim, who ran United Fruit’s agricultural school. The cane cutters’ kids were mostly illiterate. They studied practical things: farming, housekeeping, Methodist values. Daddy was conscientious about offering education, but he wouldn’t have taken urchins up off the street like my mother wanted to do. My mother was a real liberal. She fed people at the back door. She would have had them inside the house if my father didn’t put limits on her. If there was a child out in the batey who was ill or crippled or retarded, or had some sort of disease, Mother sent someone to pick him or her up and take the child to the company hospital. Christmastime, she went out into the countryside on her horse with gifts and toys. She wanted to go alone, but my father wouldn’t allow it. A United Fruit security guard rode along behind her. I guess they were more like police officers than guards; they carried guns and guamparas—that’s like a machete, with a big, flat blade for slapping people. My mother rode her horse all over the countryside. She once brought the National Geographic folks on a tour, and they took a lot of pictures. That is still the finest magazine to me. When my mother rode up, the Cubans streamed out of their houses and gathered around her. They loved her. They wanted to touch her. She had that effect.

When Daddy first laid eyes on her, he was visiting his brother up near Crawfordsville, Indiana. Mother had run out of gas. Daddy saw her walking along the side of the road and he said here came this angel. Mother had been a May Queen, and she was president of Kappa Kappa Gamma at DePauw. I had to return her sorority pin when she died. Harlan Sanders—that’s Colonel Sanders—he was from Indiana, and always in love with Mother. We were his guests at the Sanders Motor Court once, on our way to Cumberland Falls. You could tell he had that fatal thing for Mother. His hands shook and his face turned red when he greeted us. I think Daddy was amused. He didn’t mind showing her off. Mother was a beautiful woman, and she took fine care of herself. Never washed her face with soap, only cold cream, and she was health-conscious. She had the servants making yogurt back when it was still a very unusual thing to eat. Every night she sat at her desk and brushed her hair a hundred times before she went to bed. You notice those things as a boy. Twice or three times a year Daddy would take us to Miami to shop for Mother’s clothes. He’d arrange for a private room at Burdine’s. He, Del, and I would sit with Mother as the models came out in various things. If we liked what the model wore, Mother tried it on and came out and took a spin. If we agreed that it looked nice, Daddy bought it. Mother said she would never wear anything that her men didn’t approve of. At first I didn’t want to spend the afternoon in a fitting room. But then I got to liking the ritual of it, and how nice Mother dressed herself. When Del started palling around with Phillip Mackey, Del grew less interested in family things and stopped coming with us to Miami. It wasn’t as fun going without him, but it made Mother happy that I was there, and I took pride in helping her choose outfits, in being the son she could depend on. Later, when I was at military school, we dressed up for dances and functions and I knew how to put myself together because of Mother. I cared about these things. Mother said elegance was taking a plain outfit and accenting it with one flashy detail—a tie, maybe. I still think of her when I get dressed up.

Dirt shacks, no running water—the way those people lived, it’s just how life was to me. I was a child. Mother didn’t like it, but Daddy reminded her that the company paid them higher wages than any Cuban-owned sugar operation. Mother thought it was just terrible the way the Cuban plantations did business. It broke her heart, the idea of a race of people exploiting their own kind. The cane cutters were all Jamaicans, of course—not a single one of them was Cuban—but I knew what she meant: native people taking advantage of other native people, brown against black, that kind of thing. She was proud of Daddy, proud of the fact that the United Fruit Company upheld a certain standard, paid better wages than they had to, just to be decent. She said she hoped it would influence the Cubans to treat their own kind a bit better.

* * *

I knew something terrible had happened, watching Daddy take off like that, still wearing his pajama shirt. I ran back in to get dressed and heard Mother on the phone with Mr. LaDue, apologizing for calling so early. “Mr. Stites wanted me to call and inform you that there’s a fire in the cane fields,” she said. Of course it was a fire. Nothing else could have made that strange, orange l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Part Four

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- ‘The Hard Crowd’ Teaser

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Telex from Cuba by Rachel Kushner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.