PART I: PRELUDE

“You live in interesting times,” the French poet Paul Valéry told a graduating class in Paris in 1932. “Interesting times are always enigmatic times that promise no rest, no prosperity or continuity or security. Never has humanity joined so much power and so much disarray, so much anxiety and so many playthings, so much knowledge and so much uncertainty.”

Valéry spoke three years after the New York stock market crashed, opening the way to the Great Depression; one year after Japanese and Chinese troops fought for control of Manchuria; the same year famine struck the Soviet Union when communist-instituted collective farming failed to produce adequate crops; and a year before Adolf Hitler was named chancellor of Germany and a concentration camp for dissidents opened at Dachau. Economic depression, territorial expansion, the growing strength of communism and fascism: these were indeed interesting times. Political and social turmoil marked the period between World War I and World War II.

The events of the interwar years had their roots in the nineteenth century. Industrialization, expanding technologies, empire building, the search for resources and markets, nationalistic rivalries, the growth of mass political participation, and emerging and existing ideologies including Marxism and capitalism, had created conflicts within and between countries well before 1914. Not only did these interlocking issues reach a crescendo in World War I, they remained unresolved when it ended. In geographic scope, monetary cost, death tolls (estimates range between 10 and 13 million-troops), and the use of modern military technology, World War I was unparalleled. Soldiers and refugees returned to bombed-out cities and villages. Clothing, housing, and food were in short supply. Famine and the 1918–1919 influenza epidemic killed an additional 50 million people, some 500,000 of them in the United States.

The war had far less impact on the American homeland and economy. The United States had not entered the war until April 1917, three years after it began. The country did lose some 116,516 troops from battle deaths and other causes and had incurred expenses, including loans to its allies, totaling more than $7 billion—plus some $3 billion in postwar loans to Allied countries and newly formed nations. But no battles took place on U.S. territory, civilians were not killed, and American soldiers were not worn out from years of fighting. In fact, the disruption to European empires and economies and their reliance on U.S. funding actually helped the United States replace Britain as the leading financial power in the postwar world.

Despite its economic influence, and a desire to expand trade, the United States pursued a strongly isolationist postwar foreign policy in its political commitments. The conservative Republican Congress that was elected in 1918 repudiated not only the relatively progressive domestic aims of President Woodrow Wilson, but also his championing of the League of Nations. In 1920, Republicans reclaimed the White House with the election of Warren G. Harding on the platform of a “return to normalcy”—steering clear of foreign entanglements and concentrating on the business of the United States.

Treaty of Versailles

The most prominent of the six treaties that ended World War I was the Treaty of Versailles, drawn up between the Allied powers—including Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States—and Germany. (Separate treaties were signed with the other belligerents.) It was signed on June 28, 1919, and eventually ratified by every country involved except the United States. (Russia did not participate in formulating or signing the treaty.)

Germany lost European territory to Belgium, Denmark, Poland, and France; a corridor separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany; and Danzig (Gdansk) on the Polish coast became a free city with its own constitution, but under the protection of the League of Nations. Alsace-Lorraine (in the southwest corner of Germany), with its iron fields, was ceded to France, which also had the right to the coal mines in Germany’s Saar Basin. Germany lost all its colonial territories; they became mandates of Britain, France, and Japan. The left bank of the Rhine River was to be occupied by the Allies for fifteen years.

On May 27, 1919, German delegates at the Trianon Palace Hotel listen to a speech by French premier Georges Clemenceau on the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

In addition, reparations were to be paid to the Allies based on Article 231 of the treaty: “The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.” The war guilt article also accused Kaiser Wilhelm II of crimes against international morality.

Germany was prohibited from having a draft, several types of weapons, and a military or naval air force. Numbers of personnel and equipment in the army and navy were drastically reduced. Austria and Germany could not be unified without unanimous permission from the League of Nations. France and Italy particularly desired this restriction because they feared the two Germanic nations would unite to become the single most powerful country in Europe, as their close alliance had made them before World War I.

Versailles’ harsh terms toward Germany have often been blamed for fueling antagonisms that erupted into World War II. The Allies rejected German attempts to negotiate and forced the German government to accept every stipulation exactly as presented to them, including the despised war guilt clause. Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ (Nazi) Party exploited these circumstances to arouse hatred in the German people as the Nazis rose to power.

THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS

The Covenant of the League of Nations stated that it was formed “in order to promote international co-operation and to achieve international peace and security.” The original members of the League were those thirty-two countries that had signed the Treaty of Versailles. The United States never actually became a member, since Congress failed to ratify the treaty. Thirteen additional neutral countries in South America, Europe, and the Middle East were specifically invited to join the League in the Annex to the Covenant. Thus it began with forty-three members. Significantly, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Turkey, and the Soviet Union were not initially asked to join, which affected League intentions and policy as a global institution.

The League granted authority to Britain, France, and Japan to administer the former German colonies and territories of the Ottoman Empire in behalf of the people, until they could govern themselves. Although the Covenant called for the mandatories to support fair labor practices, legal justice, and “freedom of conscience and religion,” for the people living in these mandates, the system seemed little different from the claiming and control of colonies that was a hallmark of the prewar period.

Although Article 10 of the Covenant called on the members to “respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members,” none was prepared to provide troops to defend another country. But the League of Nations did deal with issues of housing, health, and education; sought to protect women and children; worked to abolish slavery and forced labor; helped to rebuild Austria, Hungary, and Bulgaria; and provided help to millions of refugees, including Russians, Greeks, and Armenians. In its humanitarian work, it was a beacon of hope to many people throughout the world.

The Treaty of Versailles also failed to resolve the underlying tensions that had preceded World War I. Versailles did not settle the struggle among countries worldwide for economic and military domination or secure the principle of self-determination for every political group and culture. It did not end conflict between communist, democratic, and later fascist ideologies; colonial and nationalist forces; and ethnic and religious groups. Rather, the treaty—and the political infighting that occurred as the various Allies negotiated terms—confirmed that control of empires, trade and resources, labor and agriculture, government and society, and defense and security were more on the minds of political leaders of every stripe than the often-expressed goals of peace and respect for all nations. This, in turn, reinforced the view of American isolationists. General Tasker Bliss, chief of the American military delegation at the Versailles negotiations, observed, “What a wretched mess it all is. If the rest of the world will let us alone, I think we had better stay on our side of the water and keep alive the spark of civilization.”

Post-Versailles: The State of the World

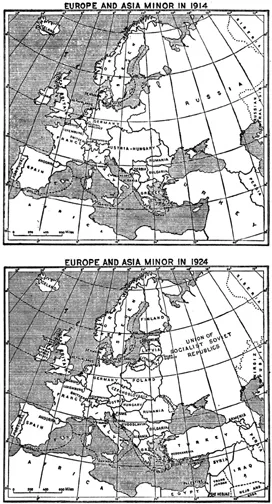

The globe looked markedly different after World War I. Not only imperial Germany, but the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires fell. Since newly communist Russia did not participate at Versailles, territory taken by Germany from Russia under the terms of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty concluded between the two countries on March 3, 1918, was now used to enlarge or create eastern European states: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland (which had declared its independence in 1917), a reconstituted Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. The political boundaries drawn after World War I trapped some ethnic populations within countries where a majority of the population had a different background (for example, Germans in Czechoslovakia), breeding interethnic conflict.

After the League mandate system added Palestine, the Transjordan, Tanganyika, and joint control with France of the Cameroons and Togoland to the British empire, Britain governed 23.9 percent of the world. Although Britain was in debt to the United States for some $4.3 billion, maintaining the empire, despite enormous cost, was one of its chief concerns, as well as maintaining naval supremacy and the balance of power on the European continent.

France, with the addition of Lebanon, Syria, and its share in Africa, governed 9.3 percent of the world. The country had borrowed $3.4 billion from the United States and had lost more men than any of the other Allies—except Russia. Most of the fiercest and prolonged fighting had taken place on French soil. France’s paramount concern during the interwar years was security, which called for retaining the upper hand in relation to Germany.

While Britain and France acquired large mandates, Italy increased its territory by only 8,900 square miles and, perhaps more insulting, received no mandate over former German colonial territory. Not only its government, but its people were bitter and frustrated with the treaty’s terms.

These maps show the boundaries of Europ...