Roger Brooke Taney* was born on St. Patrick’s Day, 1777, in a three-story white clapboard house set on the crest of a gentle hill overlooking the Patuxent River in southern Maryland. Taney’s birthplace had served as home to five generations of Taneys, beginning with the first Michael Taney, who had immigrated from England in 1660. Michael I, as he was known in Taney family lore, initially worked the land as an indentured servant. After paying off his debt, he acquired a small plot of land and gradually expanded his holdings to several thousand acres. The land was fertile and particularly conducive to the growth of tobacco, which found an eager market in Great Britain. Michael I prospered, befriended other leaders in the colony, including Lord Baltimore, and was pleased to be referred to as “Michael Taney, Gentleman.”

The flourishing tobacco economy of southern Maryland transformed the Taneys into members of that region’s landed aristocracy. Slaves labored in their fields and served them in their plantation home. Succeeding generations of Taneys rode to hounds, entertained neighbors on a grand scale, and married other members in their high social class. Michael II inherited the estate overlooking the Patuxent and married Dorothy Brooke, a descendant of Robert Brooke, who traced his family roots to William the Conqueror. Sometime between the first and fourth generation, the Taneys, who were originally members of the Church of England, converted to Catholicism.

Michael V, the future Chief Justice’s father, was educated at a Catholic English school at Saint-Omer in France before assuming his position as gentleman planter and leader of the prominent Taney family. But Michael V’s boisterous personality and restless nature were not well suited to his designated aristocratic station. He was a loud, hard-drinking sportsman who was happiest fishing, shooting wild geese, and fox-hunting. And he had a volcanic temper. In 1819, Michael stabbed another man to death in an argument over the honor of a woman. He fled to Virginia; a year later, he was thrown from a horse and died.

It was said that Roger Taney inherited his father’s temper but little else. He was a frail, bookish boy, who appeared to be greatly influenced by his mother, Monica Brooke Taney. She possessed a kind, sensitive nature, which her son lovingly recalled. “She was pious, gentle, and affectionate, retiring and domestic in her tastes,” he wrote. “I never in my life heard her say an angry or unkind word to any of her children or servants, nor speak ill of any one.” As an adult, Roger would emulate his mother in his compassionate treatment of his own children and the family’s slaves.

Roger’s older brother, Michael VI, was destined to inherit the family estate. Education, therefore, became particularly important for Roger, so that he might acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to fulfill his father’s ambition that he should become a lawyer. As small boys, Roger and his older brother walked three miles to a tutor whose qualifications were limited to a modest ability to read and write. Later, the two boys boarded at a grammar school ten miles from the Taney estate. But the teacher was delusional and drowned in the Patuxent River after acting upon his misguided belief that he could walk on water. Finally, Roger came under the excellent tutelage of Princeton-educated David English, who instructed the boy until he was sent away at the age of fifteen to Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. For the next three years, Roger took classes in ethics, metaphysics, logic, and criticism with the brilliant head of the college, Dr. Charles Nisbet, a Presbyterian minister from Montrose, Scotland. He also studied languages, mathematics, and geography with other members of the faculty. At graduation, Roger was chosen to make the valedictory address, an honor that he modestly devalued, pointing out that his selection was based neither on grades nor the faculty’s judgment, but rather on the vote of his fellow students.

Taney returned to the family estate in 1796 and spent the winter days fox-hunting and eating lavishly. In the evenings the Taney men and their male neighbors gathered around the fireside to swap stories, frequently about the courtroom triumphs of two of the state’s legendary trial lawyers, Luther Martin and William Pinckney. These anecdotes were particularly welcomed by Michael V, who made no secret of his desire to have his intense, intellectually gifted son, Roger, study law. Later that year, at the age of nineteen, Roger was dispatched to Annapolis to read law in the chambers of Jeremiah Chase, one of the three judges of the General Court. For the next three years, Taney pored over law books for twelve hours a day. And when he was not studying, he sat in court taking notes on the techniques and arguments of the leading trial lawyers.

After Taney was admitted to the bar in 1799, he anxiously prepared to try his first case in Annapolis’s Mayor’s Court. His client was a man charged with assault and battery in a fistfight in which neither combatant was severely hurt. For Taney, the details of his legal argument were the least of his problems. He was paralyzed with terror at the thought of his first courtroom argument, his fright compounded by consuming concern over his fragile health. His hands shook uncontrollably and his knees trembled throughout the ordeal of the trial. Taney, nonetheless, won the case.

Even as an experienced litigator, Taney never completely overcame a chronic panic when he rose to speak in court. “[M]y system was put out of order by slight exposure,” he recalled, “and I could not go through the excitement and mental exertion of a court, which lasted two or three weeks, without feeling, at the end of it, that my strength was impaired and I needed repose.” His worries about his health were unrelenting, and so were his courtroom successes.

After a brief time in Annapolis, Taney moved to Frederick, Maryland, where he built a thriving law practice. He married Anne Key, the sister of Taney’s close friend Frank Key (who became famous later as Francis Scott Key, the composer of the national anthem). Anne Key Taney embodied many of the attributes of Roger’s adored mother. She was gentle and kind, and appeared, over the years, to moderate her husband’s dark moods and quick temper. Together, they raised six daughters, all in Anne’s Episcopal faith. Once, when a local priest visited the Taneys to press his case for Catholicism on the Taney children, Roger abruptly interrupted, informing the clergyman that religious debate was not allowed in his home.

Michael V expected Roger to distinguish himself in state politics as well as law. Toward this end, he persuaded his son to become a candidate for the Maryland House of Delegates shortly after he had settled in Frederick. Roger ran as a member of the Federalist Party, to which the Taneys as well as virtually all other members of the landed aristocracy in southern Maryland belonged. He won the election, primarily because of his father’s influential contacts—and despite his own lack of the natural politician’s rapport with a crowd. He was defeated for reelection two years later.

The election defeat did not discourage Taney from taking an active role in Federalist politics, and he soon became a state leader of the party. Taney took forceful positions on controversial issues, none more important than his dramatic split with Federalist Party regulars over the War of 1812. No sooner had the bankers and merchants in the northeastern states, the backbone of the Federalist Party, denounced the war than Taney declared his support for it. After he was viciously attacked by Federalist Party regulars in Maryland for his position, Taney unleashed a blistering rebuttal, suggesting that his critics had placed their property interests above the nation’s honor.

Taney’s attack on the mercantile class was not so radical as it first might appear. The Taneys and other members of the planter aristocracy in southern Maryland had always been suspicious of the merchants and bankers who had served as middlemen between the tobacco planters and their foreign markets. Taney’s support for the War of 1812, and, implicitly, Republican president James Madison, allowed him to vent his hostility toward the Federalists’ mercantile class that opposed it. In so doing, Taney sounded more like a Jeffersonian Republican than a Federalist in his support for the masses against the vested commercial interests of urban America. It was a theme that Taney would strike again and again, first as a member of President Andrew Jackson’s cabinet and later as Chief Justice of the United States.

In 1816, Taney ran successfully for a five-year term in the state senate. During his legislative term, Taney acted publicly on behalf of free blacks and privately to improve the lives of his slaves. He supported state legislation to protect free blacks from unscrupulous whites who seized them for sale as slaves. He also became voluntary counsel to an organization that fought the kidnapping of free blacks and their imprisonment for lack of papers to prove their freedom. With his friend Frank Key, Taney served as an officer of a colonization society that worked to send free blacks to a colony in Africa. And Taney quietly manumitted most of his own slaves and took personal financial responsibility for supporting his older slaves, giving them wallets for small silver pieces that he replenished every month.

As a practicing attorney in Frederick, Taney was opposed to slavery and made his views known most dramatically in 1819 in his successful defense of an abolitionist preacher, the Reverend Jacob Gruber. At an early age, Gruber had left his family in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to preach the Methodist gospel throughout the countryside of the mid-Atlantic states, from New York to North Carolina. Dressed in a somber gray suit and broad-brimmed hat, Gruber exhorted the faithful to fear God and lead a righteous life. He detested alcohol, cigars, and high fashion, taking special exception to men’s walking sticks and women’s exposed petticoats. But he saved his harshest judgments for those who strayed from basic Methodist tenets, among them, the church’s belief that the institution of slavery was immoral.

On August 16, 1818, Gruber preached to three thousand men and women, including several hundred blacks, at an evening camp meeting of the Methodist Society in Hagerstown, Maryland, located in the western part of the state near the Pennsylvania border. Gruber spoke for slightly more than an hour on the subject of national sin, enumerating the obstacles to a righteous life, which included intemperance, profanity, and infidelity. Finally, he devoted the last fifteen minutes of his sermon to what he called the national sin of slavery and oppression.

“Is it not a reproach to a man to hold articles of liberty and independence in one hand and a bloody whip in the other, while a negro stands and trembles before him with his back cut and bleeding?” Gruber asked. What he termed “this inhuman traffic and cruel trade [in slaves]” had torn apart the most tender familial bonds. “That which God has joined together,” the preacher thundered, “let not man put asunder.” He condemned the slaveowners in his audience who had disregarded this divine injunction, and asked, “Will not God be avenged on such a nation as this?”

There was much grumbling among the slaveowners who attended Gruber’s sermon, and rumors quickly spread that the preacher would be jailed for his inflammatory ideas. A few weeks later, a grand jury returned a true bill charging that Gruber “unlawfully, wickedly, and maliciously intended to instigate and incite diverse negro slaves, the property of diverse citizens of the said state [of Maryland], to mutiny and rebellion.” After the indictment, Gruber was assured by a fellow Methodist clergyman that he would be represented by the finest legal counsel available in western Maryland—“Lawyer Taney, the most influential and eminent barrister in Washington and Frederick [counties].”

Taney’s first official act as Gruber’s attorney was to successfully petition to have the trial moved to a courtroom in his hometown of Frederick, away from Hagerstown, where, according to Taney, “great pains had been taken to inflame the public mind against him.” In his opening statement at the trial, which took place in March 1819, Taney reminded the three-judge panel that freedom of expression was protected by the Maryland Constitution, even a discussion of that most controversial subject, slavery. “No man can be prosecuted for preaching the articles of his religious creed,” said Taney, “unless his doctrine is immoral, and calculated to disturb the peace and order of society.” With that simple opening, Taney suggested to the judges the high legal standard they should apply to find his client guilty: the Reverend Gruber could only be convicted if his words were “immoral,” and calculated to disturb the peace.

With sure, lethal blows, Taney then proceeded to destroy the prosecutor’s case, first noting that the indictment had not accused Gruber of “immoral” speech. That left the single charge that the preacher had intended to incite the slaves to riot. But his client was no calculating incendiary, Taney insisted. No one in the crowd, he maintained, could have been surprised that Gruber, a member of a religious sect that believed slavery was a sin, would preach on the evil of the institution. If a slaveholder feared the effect that the Reverend Gruber’s words would have on his slaves, he could have kept them on the plantation. “Mr. Gruber did not go to the slaves; they came to him. They could not have come if their masters had chosen to prevent them.” Based on the facts, the judges were bound to conclude, as Taney did, that the intentions of the Reverend Gruber were pure and entirely consistent with both his religious calling and the laws of Maryland.

Had Taney rested his case there, his presentation would have been no more remarkable than that of scores of his other superb courtroom arguments. He had laid out his case to the judges in a spare, direct narrative that clung tightly to the facts and relevant law. But in this case, unlike any other that Taney tried during his distinguished career, the future author of the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott opinion chose to speak with uncharacteristic passion about the institution of slavery:

Despite his peroration at the Gruber trial, Taney remained true to his heritage as a member of the planter aristocracy of southern Maryland. While he deplored slavery at the abolitionist’s trial in 1819, he never advocated forcible elimination of the institution. For Taney, the evil of slavery could only be eliminated gradually through state laws that were supported by the voters, presumably including some of the slaveowners who had perpetuated the system. Though the record is not conclusive, Taney appeared to have opposed the Missouri Compromise in 1820 because he did not believe Congress had the authority to determine whether future states carved out of the Louisiana Territory would be slave or free.

Taney left Frederick in 1823 to establish a law office in Baltimore, and his reputation as an outstanding advocate rapidly expanded beyond Maryland’s borders. With Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster as his co-counsel, Taney made an important argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1826, representing Solomon Etting, a prominent Baltimore merchant. Etting had endorsed a security bond of the Baltimore branch of the Bank of the United States, unaware that the branch’s cashier, James McCulloch, had been systematically plundering the bank’s reserves. When Etting learned about McCulloch’s illegal practices, he indignantly refused to pay, declaring that the bank had effectively voided the contract by concealing the fact of McCulloch’s fraudulent conduct until the security was provided. The bank sued Etting and won in the lower courts.

Taney and Webster appealed to the Supreme Court, where Associate Justice Joseph Story eagerly anticipated their oral argument. The case promised relief for the justices who, according to Story, “have had but little of that refreshing eloquence which makes the labors of the law light.” Story expected Taney and Webster to illuminate the complex issues of what he called “a great case of legal morality.” Webster was well known to the justices, but Story wrote that his co-counsel, Taney, was also “a man of fine talents.” Taney and Webster’s arguments persuaded three members of the Court, including Story, that the bank had engaged in “a positive deceit by acts though not by words.” But unfortunately for Solomon Etting, an equal number of justices, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, refused to hold the bank legally responsible for its cashier’s acts. The lower court judgment, therefore, remained in effect.

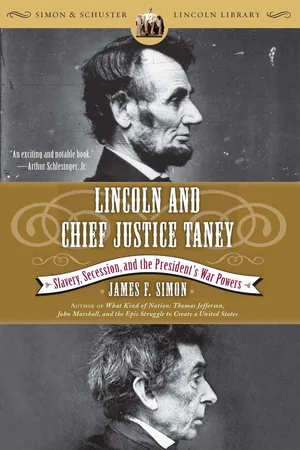

While practicing law in Baltimore, Taney reached middle age, and his frayed appearance reflected the wear and responsibility of the years. His tall frame and loosely fitting clothes would later invite comparisons with Abraham Lincoln. But Taney lacked Lincoln’s physical energy. His broad, stooping shoulders seemed to support his lank body tenuously. And yet when Taney spoke to judge or jury, he commanded their complete attention, an improbable feat given the fact that he spoke in a low, hollow voice, without gesture, literary illusion, or highly charged oratory.

William Pinckney, a superb trial lawyer himself, said that ...