Sensible investors build portfolios starting with an asset allocation that rests on the bedrock of diversification, equity orientation, and tax sensitivity. The building blocks for the portfolio consist of core asset classes that rely on market-based returns to contribute basic, category-specific characteristics to the portfolio.

Six asset classes provide exposure to well-defined investment attributes. Investors expect equity-like returns from domestic equities, foreign developed market equities, and emerging market equities. Conventional domestic fixed-income and inflation-indexed securities provide diversification, albeit at the cost of expected returns that fall below those anticipated from equity investments. Exposure to real estate contributes diversification to the portfolio with lower opportunity costs than fixed-income investments.

In the portfolio construction process, diversification requires that individual asset-class allocations rise to a level sufficient to have an impact on the portfolio, with each asset-class accounting for at least 5 to 10 percent of assets. Diversification further requires that no individual asset class dominate the portfolio, with each asset class amounting to no more than 25 to 30 percent of assets.

The principle of equity orientation induces investors to place the bulk of the portfolio in higher-expected-return asset classes. Domestic equities, foreign equities, and real estate deserve large allocations, allowing the equity-oriented asset classes to drive long-term returns. Domestic bonds and inflation-indexed bonds receive low allocations, allowing the fixed-income-oriented asset classes to provide diversification without excessive opportunity cost.

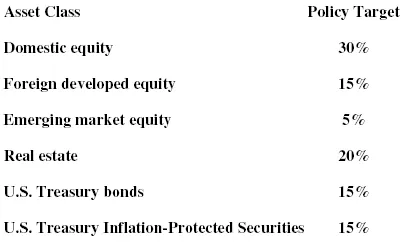

Table I.1 Well-Diversified, Equity-Oriented Portfolios Provide a Framework for Investment Success

A generic portfolio based on fundamental investment principles provides a starting point for a discussion of portfolio construction. Table I.1 contains an outline of a well-diversified, equity-oriented portfolio. Fully 70 percent of assets promise equity-like returns, meeting the requirement of equity orientation. Asset-class weights range from 5 to 30 percent of assets, meeting the requirement of diversification. A portfolio with assets allocated according to fundamental investment principles establishes a strong starting point for individual investment programs.

Ultimately, successful portfolios reflect the specific preferences and risk tolerances of individual investors. Understanding the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of asset-class exposure creates a basis for determining which asset classes to include and in which proportions to invest. Chapter 2, Core Asset Classes, offers a primer on those asset classes likely to contribute to investor goals. Chapter 3, Portfolio Construction, outlines a methodology that blends science and art in combining the core asset classes to produce a portfolio. Chapter 4, Non-Core Asset Classes, describes the shortcomings of those asset classes less likely to satisfy investor needs.

Defining asset classes combines art and science in an attempt to group like with like, seeking as an end result a relatively homogeneous collection of investment opportunities. The successful definition of an asset class produces a combination of securities that collectively provide a reasonably well-defined contribution to an investor’s portfolio.

Core asset classes share a number of critical characteristics. First, core asset classes contribute basic, valuable, differentiable characteristics to an investment portfolio. Second, core holdings rely fundamentally on market-generated returns, not on active management of portfolios. Third, core asset classes derive from broad, deep, investable markets.

The basic, valuable, differentiable characteristics contributed by core asset classes range from provision of substantial expected returns to correlation with inflation to protection against financial crises. Careful investors define asset-class exposures narrowly enough to ensure that the investment vehicle accomplishes its expected task, but broadly enough to encompass a critical mass of assets.

Core asset classes rely fundamentally on market-generated returns, because investors require reasonable certainty that the various portfolio constituents will fulfill their appointed missions. When markets fail to derive returns, investors seek superior active managers to do the job. In those cases where management proves essential to the success of a particular asset class, the investor relies on ability or good fortune in security selection to produce results. If an active manager exhibits poor skill or experiences bad luck, the investor suffers as the asset class fails to achieve its goals. Satisfying investment objectives proves too important to rely on serendipity or the supposed expertise of market players. Core asset classes, therefore, depend fundamentally on market-driven returns.

Finally, core holdings trade in broad, deep, investable markets. Market breadth promises an extensive array of choices. Market depth implies a substantial volume of offerings for individual positions. Market investability assures access by investors to investment opportunities. The basic building blocks for investor portfolios come from well-established, enduring marketplaces, not from trendy concoctions promoted by Wall Street financial engineers.

Core asset classes encompass stocks, bonds, and real estate. Asset classes that investors employ to drive portfolio returns include domestic equities, foreign developed market equities, and emerging market equities. Asset classes that investors use to create diversification include U.S. Treasury bonds, which promise protection from financial catastrophe, and U.S. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, which provide ironclad assurance against inflation-induced asset erosion. Finally, asset-class exposure to equity real estate produces a hybrid of equity-like and bond-like attributes, generating inflation protection at a lower opportunity cost than other alternatives. Core asset classes provide the tools required by investors to create a well-diversified portfolio tailored to fit investor-specific requirements.

Descriptions of the core asset classes help investors understand the role that various investment vehicles play in a portfolio context. By assessing an asset class’s expected returns and risks, likely response to inflation, and anticipated interaction with other asset classes, investors develop the knowledge required for investment success. A description of issues surrounding alignment of interests between issuers of securities and owners of securities illustrates the potential pitfalls and possible benefits of participating in certain asset categories.

Core asset classes provide a range of investment vehicles sufficient to construct a well-diversified, cost-effective portfolio. By combining the basic building blocks in a sensible manner, investors create portfolios likely to meet broad investments objectives.

DOMESTIC EQUITY

Investment in domestic equities represents ownership of a piece of corporate America. Holdings of U.S. stocks constitute the core of most institutional and individual portfolios, causing Wall Street’s ups and downs to drive investment results for many investors. While a large number of market participants rely far too heavily on marketable equities, U.S. stocks deserve a prominent position in investment portfolios.

Domestic stocks play a central role in investment portfolios for good theoretical and practical reasons. The expected return characteristics of equity instruments match nicely the needs of investors to generate substantial portfolio growth over a number of years. To the extent that history provides a guide, the long-term returns for stocks encourage investors to own stocks. Jeremy Siegel’s two hundred years of data show U.S. stocks earning 8.3 percent per annum, while Roger Ibbotson’s seventy-eight years of data show stocks earning 10.4 percent per annum. No other asset class possesses such an impressive record of long-term performance.

The long-term historical success of equity-dominated portfolios matches the expectations formed from fundamental financial principles. Equity investments promise higher returns than bond investments, although the prospect of higher returns sometimes remains unfulfilled. Not surprisingly, the historical record of generally strong equity market returns contains several extended periods that remind investors of the downside of equity ownership. In the corporate capital structure, equity represents a residual interest that possesses value only after accounting for all other claims against the company. The higher risk of equity positions leads rational investors to demand higher expected returns.

Stocks exhibit a number of attractive characteristics that stimulate investor interest. The interests of shareholders and corporate managements tend to be aligned, allowing outside owners of shares some measure of comfort that corporate actions will benefit both shareholders and management. Stocks generally provide protection against unexpected increases in inflation, although the protection proves notoriously unreliable in the short run. Finally, stocks trade in broad, deep, liquid markets, affording investors access to an impressive range of opportunities. Equity investments deserve a thorough discussion, since in many respects they represent the standard against which market observers evaluate all other investment alternatives.

Equity Risk Premium

The equity risk premium, defined as the incremental return to equity holders for accepting risk above the level inherent in bond investments, represents one of the investment world’s most critically important variables. Like all forward-looking metrics, the expected risk premium stands shrouded in the uncertainties of the future. To obtain clues about what tomorrow may have in store, thoughtful investors examine the characteristics of the past.

Yale School of Management professor Roger Ibbotson produces a widely used set of capital market statistics that reflect a seventy-eight-year stock-and-bond return differential of 5.0 percent per annum.1 Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel’s two hundred years of data show a risk premium of 3.4 percent per annum.2 Regardless of the precise number, historical risk premiums indicate that equity owners enjoyed a substantial return advantage over bondholders.

The size of the risk premium proves critically important in the asset-allocation decision. While history provides a guide, careful investors interpret past results with care. Work on survivorship bias by Phillipe Jorion and William Goetzmann demonstrates the unusual nature of the U.S. equity market experience. The authors examine the experience of thirty-nine markets over a seventy-five-year period, noting that “major disruptions have afflicted nearly all of the markets in our sample, with the exception of a few such as the United States.”3

The more or less uninterrupted operation of the U.S. stock market in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries contributed to superior results. Jorion and Goetzmann find that the U.S. market produced 4.3 percent annualized real capital appreciation from 1921 to 1996. In contrast, the other countries, many of which experienced economic and military trauma, posted a median real appreciation of only 0.8 percent per year. Thoughtful market observers place the exceptional experience of the U.S. equity markets in a broader, less compelling context.

Even if investors accept the U.S. market history as definitive, reasons exist to doubt the value of the past as a guide to the future. Consider stock market performance over the past two hundred years. The returns consist of a combination of dividends, inflation, real growth in dividends, and rising valuation levels. According to an April 2003 study by Robert Arnott, aptly titled “Dividends and the Three Dwarfs,” dividends provide the greatest portion of long-term equity returns. Of the Arnott study’s two-hundred-year 7.9 percent annualized total return from equities, fully 5.0 percentage points come from dividends. Inflation accounts for 1.4 percentage points, real dividend growth accounts for 0.8 percentage points, and rising valuation accounts for 0.6 percentage points. Arnott points out that the overwhelming importance of dividends to historical returns “is wildly at odds with conventional wisdom, which suggests that…stocks provide growth first and income second.”4

Arnott uses his historical observations to draw some inferences for the future. He concludes, with dividend yields below 2.0 percent (in April 2003), that unless real growth in dividends accelerates or equity market valuations rise, investors face a future far different and far less remunerative than the past. Noting that real dividends showed no growth from 1965 to 2002, Arnott holds out little hope of dividend increases driving future equity returns. The alternative of relying on increases in valuations assigned to corporate earnings for future equity market growth serves as a thin reed upon which to build a portfolio.

Simple extrapolation of past returns into the future assumes implicitly that past valuation changes will persist in the future. In the specific case of the U.S. stock market, expectations that history provides a guide to the future suggest that dividends will grow at unprecedented rates or that ever-higher valuations will be assigned to corporate earnings. Investors relying on such forecasts depend not only on the fundamental earning power of corporations, but also on the stock market’s continued willingness to increase the price paid for corporate profits.

As illogical as it seems, one popular bull market tome published in 1999 espoused the view that equity valuation would continue to increase unabated, arguing for a zero equity risk premium. Advancing the notion that over long periods of time equities always outperform bonds, in Dow 36,000: The New Strategy for Profiting from the Coming Rise in the Stock Market, James Glassman and Kevin Hassett conclude that equities exhibit no more risk than bonds.5 The authors ignore the intrinsic differences between stocks and bonds that clearly point to greater risk in stocks. The authors fail to consider experiences outside of the United States where equity markets have on occasion disappeared, leading to questions about the inevitability of superior results from long-term equity investment. Perhaps most important, the authors overestimate the number of investors that operate with twenty- or thirty-year time horizons and underestimate the number of investors that fail to stay the course when equity markets falter.

Finance theory and capital markets history provide analytical and practical underpinnings for the notion of a risk premium. Without expectations of superior returns for risky assets, the financial world would be turned on its head. In the absence of higher expected returns for fundamentally riskier stocks, market participants would shun equities. For example, in a world where bonds and stocks share identical expected returns, rational investors would opt for the equal-expected-return, lower-risk bonds. No investor would hold equal-expected-return, higher-risk stocks. The risk premium must exist for capital markets to function effectively.

While an expected risk premium proves necessary for well-functioning markets, Jorion and Goetzmann highlight the influence of survivorship bias on perceptions of the magnitude of the risk premium. Arnott’s deconstruction of equity returns and analysis of historical trends suggest a diminished prospective return advantage for stocks over bonds. Regardless of the future of the risk premium, sensible investors prepare for a future that differs from the past, with diversification representing the most powerful protection against errors in forecasts of expected asset-class attributes.

Stock Prices and Inflation

Stocks tend to provide long-term protection against generalized price inflation. A simple, yet elegant, means of understanding stock prices...