![]()

PART 1

STARTING OUT

In this part I will tell two true stories from my youth, strange happenings that intrigued me for the rest of my life, demanding an explanation.

Without the insight they provided, this book would never have been written.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

STRANGE HAPPENINGS

I will start by explaining what happened to me in 1948 when I got “turned around” in Cologne. It was quite a long time ago, but the memory is still very vivid.

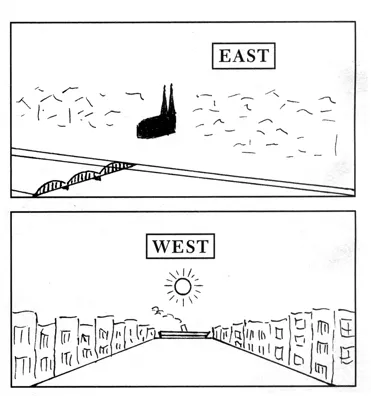

I arrived in Cologne early in the morning while it was still dark after a sleepless night in an overcrowded train from Ostend, Belgium, and slept for a couple of hours on a bench in the Central Station. After daybreak I set out towards the Rhine to find a steamer for a cruise on the river. I knew I was near the river and was puzzled when it never came in sight. Finally I asked for directions and was told to turn around. There was the river, and the steamers were in plain sight. I had been walking in the wrong direction, east instead of west, as I thought. Then I saw the sun coming out of the mist above the steamers. Sunrise in the west!

Well, that explained it. I must have become disoriented when I arrived by train during the night, so instead of going east I had actually been walking west, away from the river (Figure 1).

Now that I knew what had happened, everything would be all right, I thought. Not so! However much I told myself that the sun had to be in the east in the morning, I still felt that it was in the west and when I came to the Rhine I “saw” it flowing south. There was no way my reasoning could change my inner conviction. Apparently some mysterious direction system operating below the level of awareness had decided for me once and for all that in Cologne north was in the south. No appeal was possible.

FIGURE 1, TOP. My memory picture of Cologne as I saw it when arriving from Belgium in the west. This is when the orientation of my cognitive map of Cologne was determined.

FIGURE1, BOTTOM. Since my cognitive map was reversed, I saw the sun rising in the west the next morning.

This unresolvable conflict between the erroneous gut feeling and my rational knowledge was most unpleasant, and the harder I tried to resolve it, the more I suffered. I worried how long it would last: would all of Germany be turned around?

But once the boat got under way and out of Cologne, things straightened out. It was a relief to see the sun in the east again and the river flowing north. Apparently I had not gone crazy after all.

I returned in the evening when the sun was setting in the west and saw the tall spires of the Cologne cathedral in the north as we were going downstream towards it. As we approached the moorings, the area I knew from my morning walk came into view and then the most extraordinary thing happened. In an instant the universe spun around 180°. A very strange and most unpleasant experience. Afterwards the boat was going south, the Rhine flowed in the wrong direction, and the sunset was in the east. I left Cologne on the next train!1

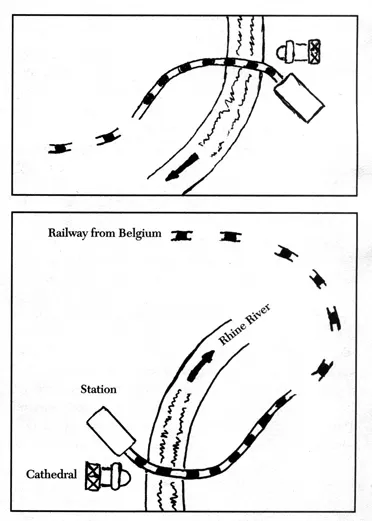

Only many years later did I figure out what had caused the reversal. Coming on a train from Belgium in the west, I assumed that I was looking over towards the east bank of the Rhine (Figure 2, top). But while I was asleep the train had crossed the Rhine. Therefore I was actually looking over towards the west bank where the center of Cologne is located (Figure 2, bottom).

FIGURE 2, TOP. My reversed map of Cologne.

FIGURE2, BOTTOM. The correctly turned map of Cologne.

There is a rule among researchers engaged in experiments that “one time is no time,” meaning that if something happens only once it does not prove anything; it must be repeated to gain credibility. I will therefore describe what happened to me in 1954 when I got “turned around” in Paris.

I arrived at the Gare du Nord railroad station in the morning after a long, tiring train journey from Sweden and took the métro (subway) to the Château d’Eau area, where I found a room in a hotel. As I looked out of my window I saw the old city gate called Porte Saint-Martin in what I felt was the north despite the fact that the map showed it was in the south. My sense of direction must have become confused during the underground ride, so that when I emerged into the street at the Château d’Eau station, my “automatic pilot” jumped to the wrong conclusion and made me feel that north was south. I stayed at the hotel for a week and made several attempts to straighten things out by approaching the hotel on foot from different directions, but as soon as I entered the area around the hotel I invariably had to go through the nasty 180° turn of the universe. A most humiliating experience for a Swedish forest hiker, who prided himself on his good sense of direction.

Finally I gave up and resigned myself to the fact that for me there was an “island” in Paris around the Château d’Eau métro station where my “inner compass” was turned around so that north was south and east was west. In order to avoid the rather upsetting sudden turnaround I experienced when I entered the area by street, I had to take the métro there. However, when I left the area on foot, I did not notice any sudden turnaround. It seemed more like passing through a zone of uncertainty that ended when I noticed familiar landmarks farther away.

Now my own experiences count for very little, since my honesty is not generally known, except to my acquaintances. I will therefore call a witness, Harold Gatty, who tells in his book Nature Is Your Guide how he got turned around at the Roosevelt airfield near New York.

It was my first flight to Long Island; and after a long and trying nineteen hours flying, we landed at Roosevelt Field in very bad weather. It was in the middle of the night. I was overtired, and when I oriented myself on leaving the airfield I established the wrong directions. I kept feeling that I knew my directions perfectly and kept finding that I was absolutely wrong. What is more, on subsequent visits I carried my capacity for illusion with me. Everything seemed reversed. I made mistakes so consistently that I began to lose all confidence in my ability to find my way.2

I hope these stories have made you nod in agreement because you have also experienced these kinds of turnarounds. For I have been told many times, when talking to people about this, that something similar had happened to them. They are often a little shy about it, thinking it means that they have a bad sense of direction when in reality it means just the opposite, that they have a good one. In fact, this sort of reversal cannot happen to somebody who has a bad sense of direction, as we will see.

These three experiences point out that humans must have a “direction sense” that we are not aware of. Our minds have a directional reference frame that we rely on to orient ourselves. It is the mainstay of our spatial system. We know in which direction to go, but if we were asked how we know, we would have no answer. It is automatic. When something goes wrong so that it works against us, it becomes a terrible nuisance; when it works right, it is a tremendous asset. And it does work right most of the time—astonishingly so. I only noticed it failing twice between the ages of twenty and forty-five. One could surmise that before maturity it would not be fully developed and after middle age it would start going downhill. Now that I am past seventy, I have to admit that my sense of direction is far worse than it used to be.

It is also noteworthy that in all three cases I have recounted there was severe fatigue involved—not only general fatigue from lack of sleep, but also a special kind of fatigue from prolonged traveling that might have had an adverse effect on the spatial system, and could be labeled “directional input overload.”

There is another neural system that operates at a level below awareness, the one that keeps us in balance as we stand and move around. It is automatic: we rely on it unthinkingly, taking it for granted, but when something goes wrong with it, we get in big trouble.

I vividly recall one particular midsummer night in Sweden in my youth when I happened to imbibe excessive amounts of alcohol. The result was spectacular. The horizon started seesawing in a marked manner, and to add injury to insult, it occasionally came up so that the ground hit me in the face. All the time I was firmly convinced that my body was perfectly vertical, it was just the horizon that misbehaved!

Alcohol changes the viscosity of the liquid in the semicircular canals of the ears, which throws into disarray the finely tuned vestibular system whose job it is to keep us upright and hold the picture of our environment stable. As a result, we feel we are upright when we are in fact reeling, and we see the horizon and our whole environment move.

Now that we have established that we possess a kind of inner compass, it is time to explore another aspect of our spatial system, the “mental map” or “cognitive map” we make of our environment. Our inner compass is useless without an inner map telling us our location and the direction where we want to go.

![]()

PART 2

COGNITIVE MAPS

In this part I try to describe our cognitive maps. This is not an easy task, since it is an elusive subject. When we first explore an area, we make a cognitive map of it, a map that guides us on later visits. Most of it takes place automatically in the unconscious part of our mind: we are not truly aware of what is going on. This can be confusing, but after reading this section—which looks at cognitive maps from different angles—I am convinced you will have acquired a good introduction to the subject.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

DESIGNING A WORKABLE

SPATIAL SYSTEM

Let us assume that we are in the admirable position of the Creator (for religious people) or Mother Nature (for romantic biologists) or evolution (for unromantic biologists) and have to design a workable spatial system for Homo sapiens. One thing we can be sure of: the “readout” from such a system, the information we used to find our way, had to be very simple. After all, we were not very sophisticated in the beginning: we had not even learned to make stone axes yet.

The system also has to work very fast. When we were face to face with a lion on the African savanna there was no time for long deliberations. We had to take off at once in the right direction when running for safety. Perception had to be followed by action instantly—just as we pull away the hand instantly when we touch something hot—or we would have been done for.

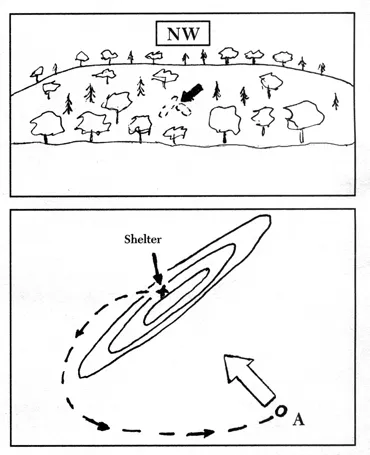

If our shelter were hidden from our view, for example behind a ridge, we had to be able to “see” exactly where it was behind that ridge. Either the ridge had to be transparent for our mind’s eye (Figure 3, top) or we had to be able to mentally lift ourselves high enough to see the shelter behind the ridge.

FIGURE 3, TOP. The arrow points to the shelter behind the ridge, seen in the correct direction and location in the cognitive map. FIGURE 3, BOTTOM. The hunters dead reckoning system automatically updates his location as he walks along. He therefore “sees” the shelter in its correct direction from A.

There is another condition that had to be satisfied, given the hurry we were in: as soon as we actually saw the shelter when we had reached the top of the ridge, we had to recognize it without delay and without fail. That means that the picture we had of it in our mind—the readout from the spatial system, in other words—had to correspond as closely as possible to what we did see when it finally came into view.

That rules out everything seen from on high, a vertical view, like the topographic maps we are so familiar with (so familiar, in fact, that it is difficult for us to imagine that a map can look any other way). Instead we had to get a mental picture of the shelter seen from eye level and from the direction we came from.

Our mental picture of the shelter also had to show it in the correct location. If it was halfway down the slope on the other side of the ridge, we had to “see” it just there. This would prevent us from possibly mistaking it for an inadequate shelter higher up or farther down the slope, a mistake that, with a lion chasing us, would have been our last.

By analyzing this hypothetical situation, we have now established that the cognitive map readout contains the correct direction to properly oriented objects seen from the side. Therefore, if the spatial system is to function, it has to include some kind of direction monitoring system, an “inner compass” which constantly provides a reliable directional reference frame for the cognitive map.

Even if some of us have never experienced the existence of this direction frame forcefully (and even painfully when something goes wrong with it, as in the previous chapter), we would have to postulate its existence, since it is the very foundation of our spatial system. It is what we call the “sense of direction,” and the fact that we intuitively label it a “sense,” coequal with the five primary senses, attests to its importance.

But even if our direction frame is in perfect order, we cannot tell the direction we want to go in unless we know exactly where we are. Direction is from here to there; if the here is unknown, the direction cannot be known. Thus we need a system that monitors our movements and integrates them so that we constantly know where we are. One could call it the position monitoring system, or as navigators say, the “dead reckoning” system (Figure 3, bottom). It is Mother Natures version of the high-tech inertial navigation system developed for nuclear submarines. The fact that in Sweden the spatial ability in general is called lokalsinne, which literally means “sense of location,” attests to the importance of the dead reckoning part of our spatial system.3

This should do it: a spatial system with a cognitive map readout, which is a picture of our surroundings including not only what we can actually see but also the familiar areas hidden from our view, all seen from where we are at the moment and thus from the side. There are two necessary support systems for this readout, the dead reckoning system, which tells us where we are, and the direction frame, which tells us in which direction we are looking.

I challenge anybody to come up with a better system!

![]()

CHAPTER 3

AN INTRODUCTION

TO COGNITIVE MAPS

Navigation is knowing where you are and how to get to where you want to go. In an unfamiliar area this means that you have to use...