![]()

Part One

THE MYSTERY OF GRACE

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

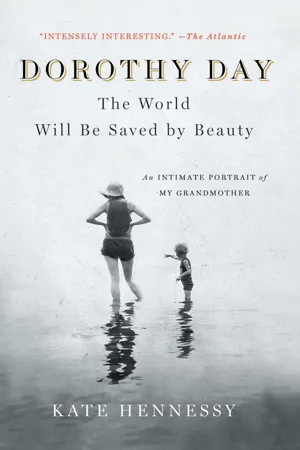

There is no time with God, my granny said, and so I set out to find Tamar and her parents when they were still together, and where do I find them but on the beach. The beach where Tamar was conceived in a cottage not twenty feet from the water, where she learned to walk in the sand, to say the rosary while following the edge of the lapping waves as the tide ebbed and flowed, and to pray to the dead spider crab hanging on the wall beside her bed. It is Staten Island, 1927, and Tamar is one and a half years old. I want to know what happened to bring these two people—Forster and Dorothy—together and what drove them apart. I want to know why Tamar would always feel this father loss, missing him even when she was too young to know what that meant. The three of them are in a rowboat, and Dorothy and Forster are silent. The happiness they had felt with each other and with the birth of Tamar is giving way to something that seems insurmountable, that seems tied to Dorothy’s constant thirst for a mystery she has yet to name. How did they get there? How far back do I need to go? To those days long before Tamar’s birth?

Let me begin again . . .

My granny said there is no time with God, and so I set out to find her when she was a young woman of twenty, the age I was when she died. The year is 1918, and it’s a bitter January morning in the predawn hours. While deep snowdrifts cover the streets of New York City, Dorothy’s fresh, new life is giving birth to struggle, pain, and questioning. Although she doesn’t yet know it, it is a time when she will turn from one path and head along another, unsure of what she is doing and where she is going. Until now, her youth and energy, her exploration and freedom have propelled her along a life of great excitement. At this moment, the hour both late and early, she is sitting in a rough, gaily decorated Greenwich Village tearoom called Romany Marie’s, and she is holding a dying man in her arms.

But wait—I must go back even further in this peeling away of the layers of the past.

Ah yes, there she is—tall and thin, more bones than flesh, with a strong, clear jaw and large oddly slanting blue eyes, thin and straight brown hair with auburn highlights, and hands and feet that are long, narrow, and graceful. It is the summer of 1916, and she is eighteen and roaming the horse-manure-spattered cobblestone streets not so far from where the Catholic Worker is now, with a nervous stride as if there were never enough time, and full of an unquenchable curiosity about people and their work, families, and traditions. Burdened by heat and loneliness, she is looking for work as a journalist, scared, full of hesitation, but determined to make her own way, following her father’s footsteps. Her two older brothers, Donald and Sam, had Pop’s blessing to become journalists (even though he had kicked them out of the house as soon as they had jobs), but she did not.

Dorothy and her father were two peas in a pod in some ways and each as bullheaded as the other. It wasn’t that John Day was against the idea of his daughter being a writer. He had started her on that path when she was a child and had helped publish her first piece for the children’s page of the Chicago Tribune, followed by book reviews for the Inter Ocean, the Chicago newspaper where he worked. Their parting of ways may have begun when Dorothy, at the age of sixteen, won a three-hundred-dollar scholarship for the University of Illinois sponsored by the Hearst papers by placing fifteenth in twenty winners of a contest in Latin and Greek. John Day wasn’t interested in higher education. He hadn’t finished high school, and neither did his two older sons. In his view, journalists didn’t need an education. They needed to start work as soon as they were able, preferably at fifteen.

But Dorothy, regardless of her love for Cicero and Virgil, turned out to be an indifferent student and careless with money. When her scholarship, which should have been sufficient to see her through her degree, ran out, she got a job cooking for a family at twenty cents an hour, then gave that up and almost starved to death. After two years, penniless and bored with her studies, Dorothy left with her family for New York City, where her parents had first met, married, and had the four oldest of the five Day children.

Enamored by the socialism she had picked up reading Jack London and Upton Sinclair and while walking through the Polish and Italian working-class neighborhoods of Chicago pushing her baby brother in a carriage, Dorothy found work with the New York Call, a paper of socialists, Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) members, trade unionists, and anarchists. When she got the job, faced with her father’s belief that it was a woman’s role to stay home and be beautiful, as Tamar described it, she left her family’s place in Brooklyn and, with not much more than her phonograph, moved into a room on Cherry Street in Manhattan. The flat was between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges and upriver from the Call’s office on Pearl Street, near the South Street Seaport. While walking under the Brooklyn Bridge on her way to and from work, she began to know the men on the streets who, as the winter months approached, warmed themselves by fires lit in barrels.

For five dollars a month Dorothy had a tiny hall bedroom in a five-story tenement with a window onto the air shaft and a toilet off the stairwell for the use of two families. As with all the tenements in the Lower East Side, there was no electricity or central heating. To keep warm, people burned coal in the fireplaces, if they could afford it, driftwood if they couldn’t, or turned on their gas ovens. The doors, halls, and stairs were made of wood, and fires were as common as bedbugs. There was also no hot water, and Dorothy used the public baths along with the Jewish women. The halls were dark and foul-smelling, but the room was clean, and the family she rented the room from provided her with a thick down comforter. They were Orthodox Jews, and when she came home after midnight from the paper, she would often find a plate of food by her bed with a note from one of the children—the parents spoke only Yiddish—explaining that they couldn’t serve milk or butter if there was meat.

Dorothy would come to claim that it was the experience of living in rooms rented out by working-class families and the long walks through the Lower East Side that would begin her affinity with the hard up and struggling. This was how her enduring curiosity about people, about their lives and their work, began. Could she ever be part of that hard life? Could she even do it? she wondered.

The Days had never been well-off, although they often lived as if they were. When Dorothy was born, Pop was working as a clerk. When he left Brooklyn for San Francisco in search of newspaper work, Dorothy’s mother, Grace, took in boarders in their Bath Beach house until she and the four children could join him. After losing everything in the 1906 earthquake, including the furniture they had shipped from New York around Cape Horn, they moved to Chicago following another one of Pop’s newspaper jobs. When that newspaper failed, Pop wrote a novel sitting at his typewriter day after day in the living room while the children were forbidden to make any noise, until he was able to find work with the Inter Ocean. When they returned to New York in 1916, he worked as the racing editor for the Morning Telegraph.

The family lived week to week, though Pop sometimes had winnings from the racetrack. He was a gambling man, my great-grandfather, a Southerner from a family of Tennessee farmers, though his father was a beloved and respected doctor, described by one of Dorothy’s cousins as kind, considerate, careless about his bills, and generous to all, poor or wealthy, black or white. Grace was from a family of whalers from upstate New York, a Northerner and a bitter pill for Pop’s mother, who took a dislike to Dorothy because she looked like Grace, the Yankee, and preferred Della, Dorothy’s sister, because her looks took after Pop. Grace came from poverty herself and had worked in a shirt factory from the age of twelve to fourteen to support her mother and three sisters after her father, Napoleon Bonaparte Satterlee, died of tuberculosis. He had been a chair maker and veteran of the Civil War—during which he was wounded in the throat and thereafter couldn’t speak above a whisper—and a survivor of Libby Prison, the second deadliest prison of the Confederacy.

Grace would come to bear five children to a man whose earnings came and went on the racetrack, who didn’t know how to share his wife with his children, and who never showed them any physical affection, though he ensured they all grew up well-read. He and Dorothy were much alike, strong-minded and stubborn—my way or the highway, as Tamar described it—and they fought. When Pop saw that Dorothy was determined to make her living as a journalist, he sent word to his cronies in the newspaper business to discourage her. Lore has it that he booted her out of the house when she found work at the Call, but then, he had booted his sons out too.

John Day liked his horses, he liked his drink, he liked his women, and he looked good at all times. He was tall, imposing, and well dressed. The Days always were beautifully dressed no matter how broke they were, and Grace, often despairing during the day, would dress up to have dinner with her children. “Get clothed and in my right mind,” she’d say. Like her mother, Dorothy dressed like a well-bred young woman even as she moved from one cold Lower East Side room to another, writing articles for a pittance, and she would maintain that sense of style long after she started the Catholic Worker, still longing for lovely clothes. “Every woman needs one good dress,” she often said, looking pointedly at Tamar.

Within a few months of working at the Call, Dorothy’s salary of five dollars a week was raised to ten. She wrote a flurry of articles over a period of five months, working from noon to midnight covering child labor, strikes, fires, starvation and evictions in the slums, food riots, and antiwar meetings. She interviewed Margaret Sanger one day and Mrs. Astor’s butler another. She and a young man, a radical writer by the name of Itzok Granich, who would come to love her, interviewed Leon Trotsky, one of the architects of the Russian revolution. She was in Madison Square Garden in March 1917 when it filled with workers celebrating the fall of the Russian czar and two days later when it held a pro-war rally. At night she attended socialist, anarchist, and IWW balls at Webster Hall on East Eleventh Street, while by day she picketed garment factories and restaurants, her first experiences of facing public indignation and hostility while being bored with the endless walking back and forth. And she also started to smoke cigarettes.

In the winter of 1916 and 1917, the Call moved from Pearl Street to St. Mark’s Place, and Dorothy’s walks were lengthened. She began to wander the streets and hike the Palisades in New Jersey with Itzok, and she became his girl. They sat and talked into the early-morning hours on the piers over the East River, where every now and then Itzok, or Irwin as he was now signing his work, would break into Yiddish folk songs or Hebrew hymns.

Irwin was a good-looking man with thick, black, and unruly hair he couldn’t be bothered to cut so he was always pushing it away. Like Dorothy, he was generous with money. He loved to explain Marx and what needed to be done to change the world, and rarely spoke about himself or his own writings. He came from an Orthodox Jewish family, theater-loving Romanian immigrants who lived on Chrystie Street in the Lower East Side. At the age of twelve Irwin got a job working in a gas mantle factory in the Bowery. At thirteen he began working for a delivery company and fell in love with horses. He said if he hadn’t become a journalist, he would have become a teamster. He had attended New York University and Harvard, but, like Dorothy, didn’t finish. University wasn’t nearly as exciting as the education that could be found on the streets.

Immigrants were arriving with an appetite for learning and attending night school, theater, and lectures by poets, professors, and philosophers who often spoke from soapboxes—Herbert Spencer on the corner of Delancey Street or Marx in the lecture halls. Atheism, anarchism, socialism, vegetarianism, women’s rights, free love, free speech, free thought—it was all in the air. The socialists were mainly immigrants and old trade unionists who sat drinking tea in East Side cafés, often speaking Yiddish. The IWWs were American, though the heyday of the great strikes was over by 1917, and the leaders were all in jail. The anarchists were a small group—Dorothy didn’t pay much attention to them—and the liberals were those who worked on the Masses, a collectively owned monthly begun in 1912 full of art, cartoons, and political commentary. In the Village, poetry, plays, and art—the Lyrical Left, as some called it—flourished along with the radical thinkers, and Irwin was involved with all of these groups. He had joined the IWW and experimented with anarchist communes. By 1914 the Masses was publishing his articles, and in 1916 he had become a member of the Socialist Party. The Provincetown Playhouse, which was housed in the stable of an old town house on Macdougal Street that the journalist John Reed had found, in its first New York City season performed his play Ivan’s Homecoming, under what they called the “war bill,” and it was through this that he introduced Dorothy to the Village.

Before the influx of the bohemians, Greenwich Village had been a neighborhood of Italian, Irish, and German immigrants, with a small segment of African Americans who helped construct the bridges, the subways, and the first of the skyscrapers. Then around 1910 a different sort of immigrant started to arrive, first from Europe and then from within the States. Some were fleeing failed marriages or family lives, drawn by something brave and new that might just might be their salvation. They were also drawn by an awareness that the world was changing, and the heartbeat of this change was to be found surrounding Washington Square Park. The north side of the park was lined with old sedate houses and tall trees in small gardens, while on the south side these bohemians gathered on narrow and crooked streets, in run-down redbrick tenement houses so miserable, people preferred to congregate in the parks, bars, and tearooms.

After rehearsals and shows, the Provincetown Players met next door at Polly Holladay’s restaurant, the first of the Village bohemian restaurants, where for fifty cents you could get a leg of lamb or roast beef and gravy, though one look at the cockroach-infested kitchen could kill your appetite. Through the Provincetown Players, Irwin introduced Dorothy to two people who would come to influence her in unexpected ways. The first was Peggy Baird Johns, a small, delicate woman seven years her senior with peculiar yellow eyes who spoke with a Long Island accent and was rumored to be the first woman in the Village to bob her hair. Peggy, it seems, knew the entire Village literary and radical crowd, including Jack London, John Reed, Emma Goldman, and Man Ray, and was married to the poet Orrick Johns, one of the first of the free-verse poets. An artist, she studied at the Art Students League under Robert Henri. She painted landscapes and portraits, and wrote poetry and had a few assignments for the Call. She believed, for a time, in free love.

Neither Dorothy nor Peggy had any real reason to be around the Provincetown Playhouse. Peggy seemed content to paint, and Dorothy occasionally read parts for absent actors during rehearsals and once auditioned for a part but was so miserable she never did it again. She was succeeding in earning her living as a journalist, however meager her wages were, but her writing dissatisfied her. She did not take to the Call’s editorial pressure to distort the truth and make things look worse than they were in order to, as she saw it, promote socialism. Dorothy disagreed with Irwin in how she saw the world. His Lower East Side and hers were not alike, though Dorothy allowed that he knew it better, having grown up on Chrystie Street. Irwin emphasized the misery and degradation of the slums, while Dorothy, though she saw the misery, also saw the dignity and courage of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. In spite of these differences, she and Irwin became engaged, and he brought her home to meet his stern and beautiful Orthodox Jewish mother, who looked at Dorothy sorrowfully, as all three of her sons were dating gentile girls at the time. She didn’t speak but she offered food. After Dorothy left, she broke the dish Dorothy had eaten from.

Dorothy quit the Call right before the Selective Service Act was passed in May 1917. All the young men argued about what to do while Dorothy worked briefly for the Collegiate Anti-Militarism League at Columbia University before bumping into Floyd Dell, the managing editor of the Masses, and becoming his assistant. She loved her work at the Masses. The publication took itself less seriously than the Call, and it published ideas Dorothy had never seen—depictions of Christ as a longshoreman or as a fisherman sympathetic to unions. “What a glowing word it was to us then,” she wrote of her time at the paper almost thirty years later. “To speak to the Masses. To write to the Masses, to be a part of the Masses.” Her own first contribution was a poem followed by a handful of book reviews. Generally, though, her duties were to answer the mail and send rejection slips to some of the best poets of the day with one word written on it, “Sorry.” Floyd Dell also taught her how to dummy up the paper for the printers, a skill she would come to need when she began her own paper. Then the editor, Max Eastman, left to go on a fund-raising tour, while Floyd took a month’s vacation to write a novel, and so it was left to Dorothy to make up what turned out to be the last issue before the Masses was shut down by the government for its anticonscription stance.

Though the first US forces were being sent to France, the summer of 1917 was a happy one for Dorothy. After a winter of living in unheated rooms, she had moved to a fifth-floor walk-up above the Provincetown Playhouse, rented for the summer from the novelist and critic Edna Kenton. There every night fevered young men gathered to talk the hours away as the threat of the draft hung over them. There seemed to be nothing they could do, so she and Irwin would head out to Staten Island for picnics on the beach and to gather shells and stones. At night they roamed the streets, and Dorothy would invite back to the apartment homeless people she met in the park.

“It’s your religious instinct,” Irwin said to her, the first of her friends to recognize this aspect of Dorothy, even though he would become a lifelong member of the Communist Party.

By November, Dorothy was back to her stream of cold rented rooms. With the suppression of the Masses and the arrest of the editors for conspiring to obstruct war conscription, Dorothy was unemployed and at loose ends when Peggy showed up with an offer she couldn’t refuse.

Peggy may have been easy to dismiss as an uncommitted and free-spirited woman, but she was brave. Caught in one of the many riots at Union Square in 1915, she had protected a deaf and mute boy about to be battered by the police by throwing her tiny arms around the boy and berating the officers until they backed off. Then in August 1917 she had gone down to Washington, DC, to ...