![]()

The 2000 presidential election between George Bush and Al Gore confronted the American people with a stark choice between two different visions of the future. Few remember that exactly one hundred years before, the American people had been asked to make a similar choice. They were asked to decide whether the United States should be a republic or an empire.

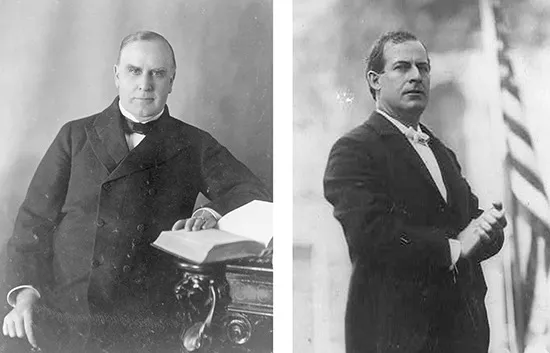

Incumbent Republican president William McKinley’s vision of the American future lay in “Free Trade” and overseas empire. By contrast, Democrat William Jennings Bryan was an outspoken anti-imperialist.

Few noticed a third choice—Socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs. The socialist movement represented the new working class. To socialists, empire meant one thing and one thing only—exploitation.

McKinley ran touting a soaring economy and a victory over Spain in the war of 1898. McKinley believed that America must expand to survive.

Bryan, a Nebraska populist known as “the Great Commoner,” was an enemy of industrial tycoons and bankers. He was convinced that McKinley’s vision would bring disaster. He quoted Thomas Jefferson’s comment that “If there be one principle more deeply rooted than any other in the mind of every American, it is that we should have nothing to do with conquest.”

Having now annexed several foreign colonies—the Philippines, Guam, Pago Pago, Wake and Midway islands, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico—and asserted practical control over Cuba, the United States was about to betray its most precious gift to mankind.

The presidential election of 1900 pitted Republican William McKinley (left), a proponent of American empire and a staunch defender of the eastern establishment, against Democrat William Jennings Bryan (right), a midwestern populist and outspoken anti-imperialist. With McKinley’s victory, Bryan’s warnings against American empire would, tragically, be ignored.

While most Americans thought the United States had fulfilled its “manifest destiny” by spreading across North America, it was William Henry Seward, secretary of state to both Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, who articulated a far more grandiose vision of American empire. He set his sights on acquiring Hawaii, Canada, Alaska, the Virgin Islands, Midway Island, and parts of Santo Domingo, Haiti, and Colombia. A lot of this dream would actually come true.

But while Seward dreamed, the European empires acted. Britain led the way in the last thirty years of the nineteenth century, gobbling up 4.75 million square miles of territory, an area significantly larger than the United States. Britain, like the Romans of yore, believed her mission was to bring civilization to mankind. France added 3.5 million square miles. Germany, off to a late start, added one million. Only Spain’s empire was in decline.

By 1878, European empires and their former colonies controlled 67 percent of the earth’s land surface. And by 1914, they controlled an astounding 84 percent. By the 1890s, Europeans had carved up 90 percent of Africa, the lion’s share claimed by Belgium, Britain, France, and Germany.

The United States was anxious to make up for lost time, and, although empire was a hostile concept to Americans, most of whom had come from immigrant stock, it was now an era dominated by the robber barons—in particular, an aristocracy known as the “400,” with their huge estates, private armies, and legions of employees. Men like J. P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and William Randolph Hearst held enormous power.

The capitalist class, haunted by visions of the revolutionary workers who formed the Paris Commune of 1871, conjured up similar nightmarish visions of radicals upsetting the system in the United States. These radicals or communards were also called communists more than fifty years before the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Jay Gould’s fifteen-thousand-mile railroad network epitomized the worst of the robber barons. Gould was perhaps the most hated man in America, having once boasted that he could “hire one half of the working class to kill the other half.”

When the financial panic of “Black Friday” 1893 hit Wall Street, it triggered the nation’s worst depression to date. Mills, factories, furnaces, and mines shut down everywhere in large numbers. Four million workers lost their jobs. Unemployment reached 20 percent.

The American Railway Union headed by Eugene Debs responded to layoffs and pay cuts by George Pullman’s Palace Car Company and shut down the nation’s railroads. Federal troops were sent in on the side of the railroad magnates. Dozens of workers were killed and Debs spent six months in jail.

The socialists, trade unionists, and reformers at home protested that capitalism’s cyclical depressions resulted from the underconsumption of the working class. In his pioneering photography, Jacob Riis shocked the nation by documenting the misery of New York City’s poor. Working-class leaders were arguing for redistributing wealth at home so that working people could afford to buy the goods they produced in America’s farms and factories.

But the 400—the oligarchs—responded that this was a form of socialism. They said there could be a bigger pie for all and argued that the U.S. had to compete with foreign empires and dominate the trade of the world so that foreigners would absorb America’s growing surplus. The profit was clearly abroad—in trade, cheap labor, and cheap resources.

The chief prize was China. To tap this vast market, the U.S. would need a modern, steam-powered navy and bases around the world to compete with the British Empire, with its major concession at the port of Hong Kong. Russia, Japan, France, and Germany were all clawing to get in.

Businessmen began pressing for a canal across Central America, which would help open the door to Asia.

In 1898, in this climate of global competition, the United States annexed Hawaii. Almost one hundred years later, a U.S. congressional resolution apologized “to Native Hawaiians” for the deprivation of their right “to self-determination.”

Cuba, less than one hundred miles from the shores of Florida, had revolted against the corrupt Spanish rule, and the Spanish reacted by incarcerating much of the population in concentration camps where ninety-five thousand died of disease. As the fighting increased, powerful bankers and businessmen, like Morgan and the Rockefellers, who had millions invested on the island, demanded action from the president—to safeguard their interests.

President McKinley sent the USS Maine to Havana harbor as a signal to the Spanish that the U.S. was keeping an eye on American interests.

On a night in February 1898, with the tropical heat more than one hundred degrees, the Maine suddenly exploded, killing 254 seamen, allegedly sabotaged by the Spanish. The U.S. “Yellow Press,” led by William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, led a crazed tabloid reaction and created a vigilante climate for war.

The Journal cried: “Remember the Maine, To Hell With Spain!” Millions read it, convinced that Spain, this decaying Catholic power, was capable of any evil deed to preserve her empire. When McKinley declared war, Hearst took credit: “How do you like the Journal’s war?” he asked.

Often remembered by Teddy Roosevelt’s symbolically colorful charge up San Juan Hill, the Spanish-American War was over in three months. Secretary of State John Hay called it a “splendid little war.” Out of almost fifty-five hundred U.S. dead, fewer than four hundred died in battle, the rest succumbing to disease.

Sixteen-year-old Smedley Darlington Butler lied about his age and signed up with the marines. He would become one of America’s most famous military heroes, winning two medals of honor in a career that would span America’s early descent into global empire.

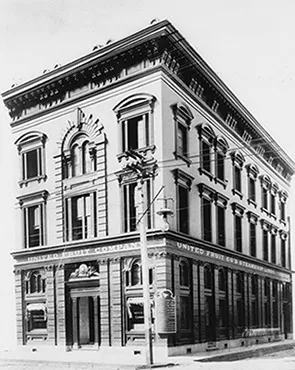

With victory, American businessmen swept in, grabbing assets where they could, essentially making Cuba into a protectorate. United Fruit Company locked up two million acres of land for sugar production. By 1901, Bethlehem Steel and other U.S. businesses owned over 80 percent of Cuban minerals.

More than seventy years later, in 1976, an under-reported official investigation by the navy found that the most probable cause of the sinking of the Maine was a boiler that exploded in the tropical heat, causing the ship’s ammunition store to explode. As with Vietnam and the two Iraq wars, the U.S., basing its reaction on false intelligence, went to war because it wanted to.

In the glow of victory, however, the U.S. found itself with a much bigger problem. It had acquired from the Spanish a gigantic but ramshackle land mass in the Far East—the Philippine Islands—which were viewed as an ideal refueling stop for China-bound ships. As in the invasion of Baghdad in 2003, the fighting there began successfully. Commodore George Dewey had destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in May 1898. One anti-imperialist noted, “Dewey took Manila with the loss of one man, and all our institutions.”

The Anti-Imperialist League, founded in Boston in 1898, sought to block U.S. annexation of the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Its ranks included Mark Twain, who famously asked, “Shall we go on conferring our Civilization upon the peoples that sit in darkness, or shall we give those poor things a rest?”

President McKinley chose the former, opting finally for annexation. “There was nothing left for us to do,” he declared, “but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.”

McKinley ran into one major problem—the Filipinos themselves. Under the fiery leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo, the Filipinos had established their own republic in 1899, after being freed from Spain, and, like the Cuban rebels, expected the United States to recognize it. They had overestimated their ally. And now they fought back. After one protest, Americans lay dead on the streets of Manila. America’s Yellow Press cried out for vengeance against the barbarians. Torture, including waterboarding, became routine. The insurgents, or “our little brown brothers” as William Howard Taft, the governor-general of the Philippines, called them, were pumped full of salt water until they swelled up like toads to “make them talk.” One soldier wrote home, “We all wanted to kill ‘niggers.’ . . . This shooting human beings beats rabbit hunting all to pieces.”

It was a war of atrocities. When rebels ambushed American troops on the island of Samar, Colonel Jacob Smith ordered his men to kill everyone over the age of ten and turn the island into “a howling wilderness.”

More than four thousand U.S. troops would not return from this guerilla war, which lasted three and a half years. Twenty thousand Filipino guerillas were killed, and as many as two hundred thousand civilians died—many from cholera. But because of distorted press reports, mainland Americans comforted themselves with the thought that they had spread civilization to a backward people.

American society grew more callous from this war. The doctrine of Anglo-Saxon superiority that justified a nascent empire was also poisoning social relations at home as southern racists, resorting to similar arguments, intensified their campaign to reverse the outcome of the American Civil War and passed new Jim Crow laws enforcing white supremacy and segregation.

Plowing on a Cuban sugar plantation.

The United Fruit Company office building in New Orleans. The Spanish-American War proved quite profitable for American businessmen. Once the war in Cuba ended, United Fruit took 1.9 million acres of Cuban land at 20 cents an acre.

In China, a similar yearning for independence led to the homegrown Boxer Rebellion of 1898 to 1901. Nationalist-minded Chinese rose up with fury to murder missionaries and throw out all foreign invaders. McKinley sent five thousand American troops to help the Europeans and the Japanese defeat the rebels.

Lieutenant Smedley Butler was in the invading force leading his Marines into Beijing where he saw firsthand the way the victorious Europeans treated the Chinese. He was disgusted.

During the Spanish-American War in the Philippines, atrocities were common. U.S. troops employed the torture we now called waterboarding. One reporter wrote “our soldiers pumped salt water into men to ‘make them talk.’ ”

Thus, as in 2008, the 1900 American election took place with U.S. troops tied down in numerous countries—in this case, China, Cuba, and the Philippines. And yet, McKinley, basking in the glow of victory over Spain, beat Bryan by a wider margin than he had in 1896. Socialist Eugene Debs barely registered with under one percent. Americans had clearly endorsed McKinley’s vision of trade and empire.

At the height of his popularity, in 1901, McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist. The assassin had complained about American atrocities in the Philippines. The new president, Theodore Roosevelt, an even more unabashed imperialist, continued McKinley’s expansionist policies. And Roosevelt, orchestrating a revolution in Panama, a province of Colombia, signed a treaty with the newly created Panamanian government to lease the Canal Zone, receiving the same rights of intervention the U.S. had forced upon Cuba. The canal was built with great difficulty and finally opened in 1914.

The bodies of dead Filipinos. A Philadelphia reporter wrote that soldiers stood Filipinos on a bridge, shot them, and floated the corpses down the river for all to see.

In the years to follow, U.S. Marines were repea...