- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

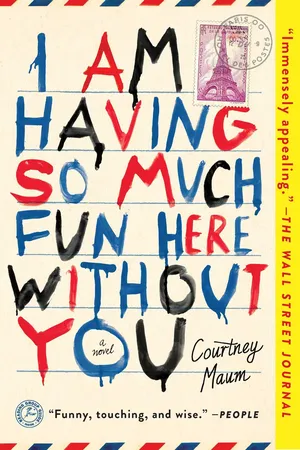

I Am Having So Much Fun Here Without You

About this book

In this reverse love story set in Paris and London, which The Wall Street Journal hailed as “funny and soulful…immediately appealing,” a failed monogamist attempts to woo his wife back and to answer the question: Is it really possible to fall back in love with your spouse?

Despite the success of his first solo show in Paris and the support of his brilliant French wife and young daughter, thirty-four-year-old British artist Richard Haddon is too busy mourning the loss of his American mistress to a famous cutlery designer to appreciate his fortune.

But after Richard discovers that a painting he originally made for his wife, Anne—when they were first married and deeply in love—has sold, it shocks him back to reality and he resolves to reinvest wholeheartedly in his family life…just in time for his wife to learn the extent of his affair. Rudderless and remorseful, Richard embarks on a series of misguided attempts to win Anne back while focusing his creative energy on a provocative art piece to prove that he’s still the man she once loved.

Skillfully balancing biting wit with a deep emotional undercurrent, this “charming and engrossing portrait of one man’s midlife crisis” (Elle) creates the perfect picture of an imperfect family—and a heartfelt exploration of marriage, love, and fidelity.

Despite the success of his first solo show in Paris and the support of his brilliant French wife and young daughter, thirty-four-year-old British artist Richard Haddon is too busy mourning the loss of his American mistress to a famous cutlery designer to appreciate his fortune.

But after Richard discovers that a painting he originally made for his wife, Anne—when they were first married and deeply in love—has sold, it shocks him back to reality and he resolves to reinvest wholeheartedly in his family life…just in time for his wife to learn the extent of his affair. Rudderless and remorseful, Richard embarks on a series of misguided attempts to win Anne back while focusing his creative energy on a provocative art piece to prove that he’s still the man she once loved.

Skillfully balancing biting wit with a deep emotional undercurrent, this “charming and engrossing portrait of one man’s midlife crisis” (Elle) creates the perfect picture of an imperfect family—and a heartfelt exploration of marriage, love, and fidelity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

MOMENTS OF great import are often tinged with darkness because perversely we yearn to be let down. And so it was that I found myself in late September 2002 at my first solo show in Paris feeling neither proud nor encouraged by the crowds of people who had come out to support my paintings, but saddened. Disappointed. If you had told me ten years ago that I’d be building my artistic reputation on a series of realistic oil paintings of rooms viewed through a keyhole, I would have pointed to my mixed-media collages of driftwood and saw blades and melted plastic ramen packets, the miniature green plastic soldiers I had implanted inside of Bubble Wrap, I would have jacked up the bass on the electronic musician Peaches’ Fancypants Hoodlum album and told you I would never sell out.

And yet here I was, surrounded by thirteen narrative paintings that depicted rooms I had lived in, or in some way experienced with various women over the course of my life, all of these executed with barely visible brushstrokes in a palette of oil colors that would look good on any wall, in any context, in any country. They weren’t contentious, they certainly weren’t political, and they were selling like mad.

Now, my impression that I’d sold out was a private one, shared neither by my gallerist, Julien, happily traipsing about the room affixing red dots to the drywall, nor by the swell of brightly dressed expatriates pushing their way through conversations to knock their plastic glasses of Chablis against mine. There was nothing to be grim about; I was relatively young and this was Paris, and this night was a night that I’d been working toward for some time. But from the minute I’d seen Julien place a red sticker underneath the first painting I’d done in the series, The Blue Bear, I’d been plagued by the feeling that I’d done something irreversible, that I wasn’t where I was supposed to be, that I hadn’t been for months. Worse yet, I had no anchor, no one to set me back on course. My wife of seven years, a no-nonsense French lawyer who had stuck by my side in grad school as I showcased found sculptures constructed from other people’s rubbish and dollhouses made out of Barbie Doll packaging, was a meter of my creative decline. Anne-Laure de Bourigeaud was not going to lie and tell me that I’d made it. The person who would have, the one person who I wanted to comfort and reboost me, was across the Channel with a man who was more reliable, easygoing, more available than me. And so it fell to the red stickers and the handshakes of would-be patrons to fuel me with self-worth. But halfway through the evening, with my own wife brightly sparkling in front of everyone but me, I was unmoored and drifting, tempted to sink.

• • •

In the car after the opening, Anne thrust the Peugeot into first gear. Driving stick in Paris is cathartic when she’s anxious. I often let her drive.

Anne strained against her seat belt, reaching out to verify that our daughter was wearing hers.

“You all right, princess?” I asked, turning around also.

Camille smoothed out the billowing layers of the ruffled pink tube skirt she’d picked out for Dad’s big night.

“Non . . .” she said, yawning.

“You didn’t take the last Yop, right?” This was asked of me, by my wife.

The streetlight cut into the car, illuminating the steering wheel, the dusty dashboard, the humming, buzzing electroland of our interior mobile world. Anne had had her hair done. I knew better than to ask, but I recognized the scent of the hairspray that made its metallic strawberry way, twice a month, into our lives.

I looked into her eyes that she had lined beautifully in the nonchalant and yet studied manner of the French. I forced a smile.

“No, I didn’t.”

“Good,” she said, edging the car out of the parking spot. “Cam-Cam, we’ll have a little snack when we get home.”

Paris. Paris at night. Paris at night is a street show of a hundred moments you might have lived. You might have been the couple beneath the streetlamp by the Place de la Concorde, holding out a camera directed at themselves. You might have been the old man on the bridge, staring at the houseboats. You might have been the person that girl was smiling in response to as she crossed that same bridge on her cell phone. Or you might be a man in a shitty French export engaged in a discussion about liquid yogurt with his wife. Paris is a city of a hundred million lights, and sometimes they flicker. Sometimes they go out.

Anne pushed on the radio, set it to the news. The molten contralto of the female announcer filled the silence of our car. “At an opening of a meeting at Camp David, British Prime Minister Tony Blair fully endorsed President Bush’s intention to find and destroy the weapons of mass destruction purportedly hidden in Iraq.” And then the reedy liltings of my once-proud prime minister: “The policy of inaction is not a policy we can responsibly subscribe to.”

“Right,” said Anne. “Inaction.”

“It’s madness,” I said, ignoring her pointed phrasing. “People getting scared because they’re told to be. Without asking why.”

Anne flicked on the blinker.

“It’s mostly displacement, I think. Verschiebung.” She tilted her chin up, proud of her arsenal of comp lit terms stored from undergrad. “The big questions are too frightening. You know, where to actually place blame. So they’ve picked an easy target.”

“You think France will go along with it?”

Her eyes darkened. “Never.”

I looked out the window at the endless river below us, dividing the right bank from the left bank, the rich from the richer. “It’s a bad sign, though, Blair joining up,” I added. “I mean, the British? We used to question things to death.”

Anne nodded and fell silent. The announcer went on to summarize the fiscal situation across the Eurozone since the introduction of the euro in January of 2002.

Anne turned down the volume and looked in the rearview mirror. “Cam, honey. Did you have a good time?”

“Um, it was okay,” our daughter, Camille, said, fiddling with her dress. “My favorite is the one with all the bicycles and then the, um, the one in the kitchen, and then the one with the blue bear that used to be in my room.”

I closed my eyes at all the women, even the small ones, who wield words like wands; their phrases sugary and innocuous one minute, corrosive the next.

Aesthetically, The Blue Bear was one of the largest and thus most expensive paintings in the show, but because I had originally painted it as a gift for Anne, it was also the most barbed.

At 117 x 140 cm, The Blue Bear is an oil painting of the guest room in a friend’s rickety, draft-ridden house in Centerville, Cape Cod, where we’d planned to spend the summer after grad school riding out the what-now crests of our midtwenties and to consider baby-making, which—if it wouldn’t answer the “what now?” question—would certainly answer “what next?”

The first among our group of friends to get married, it felt rebellious and artistic to consider having a child while we were still young and thin of limb and riotously in love. We also thought, however, that we were scheming in dreamland, safe beneath the mantra that has been the downfall of so many privileged white people: an unplanned pregnancy can’t happen to us.

Color us surprised, then, when a mere five weeks after having her IUD removed, Anne missed her period and started to notice a distinct throbbing in her breasts. We thought it was funny—so symbiotic were we in our tastes and desires that a mere discussion could push a possibility into being. We were delighted—amused, even. We felt blessed.

During those first few weeks on the Cape, I was still making sculptures out of found objects, and Anne, a gifted illustrator, was interspersing her studies for the European bar with new installments of a zine she’d started while studying abroad in Boston. A play on words with “Anne” (her name) and âne (the French word for “donkey”), Âne in America depicted the missteps of a shy, pessimistic Parisian indoctrinated into the boisterous world of cotton-candy-hearted, light-beer-guzzling Americans who relied on their inexhaustible optimism to see them through all things.

But as the summer inched on and I watched her caress her growing belly as she read laminated hardcovers from the town library, a curious change came over this Englishman who up until that point had been the enemy of sap. I became a sentimentalist, a tenderheart, an easy-listening sop. Much like how the lack of oxygen in planes makes us tear up at the most improbable of romantic comedies, as that child grew within Anne into a living, true-blue thing instead of a discussed possibility, I lost interest in the sea glass and the battered plastic cans and the porous wood I’d been using all summer and was filled with the urge to paint something lovely for her. For them both.

The idea of painting a scene viewed through a keyhole came to me when I happened upon Anne in the bedroom one morning pondering a stuffed teddy bear that our friends, the house’s owners, had left for us on a chair as an early baby gift. They were, at that point, our closest friends and the first people we had told about the pregnancy, but there was something about that stuffed animal that was both touching and foreboding. Would the baby play with it? Would the baby live? I could see the mix of trepidation and excitement playing over Anne’s face as she turned the stuffed brown thing over in her hands, and it comforted me to know that I wasn’t alone with my roller-coaster rides between pridefulness and fear.

And still—Anne is a woman, and I, rather evidently, am not. There was a great difference between what was happening to her and what was potentially happening—going to happen—to us. Which is how I got the idea to approach the scene from a distance, as an outsider, a voyeur.

Except for the tattered rug and the rocking chair beside a window with a view of the gray sea, I left the room uninhabited save for the stuffed bear that I painted seated on the rocking chair, a bit larger than it was in real life, and not at all brown. I painted the bear blue, and not a dim pastel color that might have been a trick of the light and sea, but a vibrating cerulean that lent to the otherwise staid atmosphere a pulsating point of interest. Unsettling in some lights, calming in others—the blue stood for the thrill of the unknown.

When I gave the painting to Anne, she never asked why the bear was blue. She knew why, inherently, and in the giving of the painting, I felt doubly convinced that I loved her, that I truly loved her, that I would love her for all time. What other woman could wordlessly accept such a confession? A tangible depiction of both happiness and fear?

In the fall, that painting traveled with our belongings in a ship across the Atlantic, and it waited in a Parisian storage center until the birth of our daughter, when we finally had a home. We hung it in the nursery, ignoring the comments from certain friends and in-laws that the bear would have been a lot less off-putting and child appropriate if it hadn’t been blue. The very fact that other people didn’t seem to “get it” convinced us that we had a shared sensibility, something truly special, making the painting more important than a private joke.

We continued feeling that way until Camille turned three and started plastering her walls with her own drawings and paper cutouts and origami birds, and we began to feel like we’d enforced something upon her that only meant something to us. So we put it in the basement, intending to scout for a new bookshelf system so that we would have enough wall space to hang the painting in our bedroom. But then I met Lisa, and too much time had passed, and when The Blue Bear was brought up, the discussions were accusatory, spiteful. And so it stayed in the basement, hidden out of sight, not so much forgotten as disdained.

Months later, when I st...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Acknowledgments

- Permissions

- Reading Group Guide

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access I Am Having So Much Fun Here Without You by Courtney Maum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Literatura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.