![]()

PART I

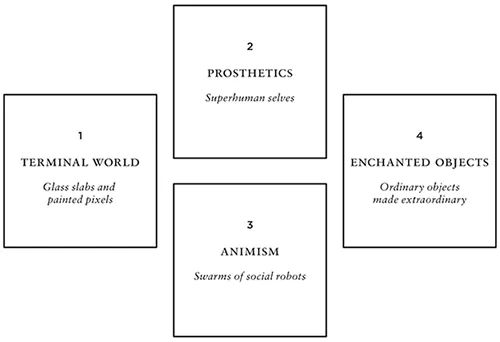

FOUR FUTURES

![]()

CHAPTER 1

TERMINAL WORLD: THE DOMINATION OF GLASS SLABS

BEFORE DELVING FURTHER into the world of enchanted objects, let’s explore the future of the other three trajectories a bit more, starting with Terminal World. Today, we find ourselves in a convergence-obsessed world, where iThings rule. How did we get here? Why has the glass slab emerged as the jealous king of things?

It is partly a matter of Newton’s third law (“For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction”—in this case, when one company puts out the next-version glass slab, others respond by putting out yet another) and partly a matter of money. Making screen-based devices—from iPod nanos to smartphones to ebooks to tablets to flat-screen TVs—is a monster wave sweeping up every consumer electronics category with its massive momentum. Industry analysts, investors, entrepreneurs, app stores—the entire high-tech ecosystem—can’t stop staring into the screen. Competition is intense around all the elements that make this Terminal World tick. The market for the manufacturing of pixels is staggering. Samsung, LG, Sony, and Sharp—and hundreds of suppliers who assemble components and products for these companies—are churning out millions of screens, and making billions of dollars of profit, each year.

Once you’re surfing a technology wave this big, it’s a huge risk to try to convince your boss or board of directors to fund anything other than another glass slab. Advocating for the next disruptive technology could mean professional suicide. As Harvard Business School legend Clayton Christensen explains in The Innovator’s Dilemma, disruption is rarely funded by incumbents. Companies, systems, and institutions with strong vested interests in the Terminal World must invent incremental ways to gain a strategic edge on their competitors. In any mature industry, including screen-making, leaders find themselves dealing with constantly falling retail prices and are forced to compete on volume—trying to produce screens at the lowest cost and then sell them in huge quantities—or by pushing the technology forward with modest new features and capabilities and getting the new models to market faster than the others in the game. There is, right now, so much glass slab development activity that it will keep the Terminal World companies busy for years to come. The immediate next generation of products will be screens that are thinner, and remarkably larger than they are now, with more pixels per inch. Then will come organic light-emitting diode (OLED) screens with their richer blacks, and these will push past the old LED tech, which only a few years ago unseated plasma. The colors will be brighter, refresh rates higher, bezels thinner, and contrast ratios higher, so the images will look more vibrant in any kind of lighting. We will see displays in new physical forms—such as the foldable, flexible screen that you can tuck in your pocket or wrap around a building—and quantum dot (QD) displays, composed of tiny light-emitting nanoparticles that can create colors that are even more vibrant, purer, and subtler and in a wider range of tones.1

I spend a good deal of time with large companies (especially those associated with MIT), such as Cisco, Panasonic, LG, and Samsung. I see how challenging it is for them to shift their mind-set and pivot away from the Terminal World. When you sell pixels, it’s hard to imagine anything that’s not a screen. For these companies, the future of computing is not even worth debating: screens and more screens. If your billion-dollar business is selling TVs, tablet screens, and data projectors or the apps that run on them, it’s hard to consider any other future, and even if you do, it’s tough to figure out how your supertanker of a company could shift course to get there.

As a result, the Terminal World will continue to expand, consuming everything in its path. Not only is the market huge, with companies committed to it, but other factors will fuel its growth. The cost of pixels is constantly plummeting. Almost any surface can now be fitted out with a smart screen of some size, and the supply of information and content to pump into those displays is endless.

What’s more, the amount of screen-based information that humans are capable of taking in is limitless. So, even if we’re not staring directly into our smartphone or television, our peripheral vision will be saturated and distracted by dense, fast, colorful information and content that swirls at the edge of our view—as Google Glass would have it.

It’s already happening. Microsoft occupies a building near my office at the Cambridge Innovation Center in Kendall Square. After being a fairly anonymous tenant in the building, Microsoft built a new, double-height entry with a big screen (perhaps thirty feet diagonally) on the interior wall, facing outward. The exterior wall is glass, so the street is dominated by the images playing constantly on that screen, totally altering the character of the neighborhood. Although the area is home to technology start-ups, big tech companies, and MIT buildings, this kind of screen domination is new.

Does the expansion of the Terminal World, even into my own neighborhood, bother me? Strangely, no. Why? Because it’s hapless, obvious, and inevitable. Should we be surprised that Microsoft installed a big screen on its building to present marketing messages for all the world to see? Hardly. The screen is a blunt instrument.

Screens will continue to spread like wildfire across the landscape and into neighborhoods and places that were previously screen-free, funded largely by advertisers and sponsors seeking new ways to channel messages to affect buying habits and drive cost savings by encouraging certain types of behavior. In health care, for example, companies like United, Cigna, Humana, and Blue Shield will subsidize the pixelization of many surfaces in your home because ambient images and messages are so potent at nudging you toward a healthier lifestyle, which can lower the cost of medical care. Your living room, kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom will take on the sponsor-saturated character of today’s baseball park with attention-grabbing messages displayed on every available surface. At North Station, one of Boston’s main commuter-rail terminals, screens are placed almost indiscriminately, as if any space without a screen seems old-fashioned. We already see screen displays in many elevators. Expect to see more in any high-traffic public spaces such as malls and bus stops. Even the most private of public spaces such as bathroom mirrors, walls above urinals, and bathroom stalls have screens. Gas stations are following the trend, with terminals at the pump to further monetize your 180 seconds of idle eyeball time while you’re filling up the tank, enticing you to step inside to buy a slushie or a high-fructose, high-margin treat. Many of these public screens also contain a camera that can sense when you’re looking at it and recognize certain characteristics about you—age, gender, ethnicity, the car you’re driving, the brands you’re wearing—then display the products its algorithm thinks you would like the most.

Microsoft and many other companies are trying to rethink how people interact with the glass slab—with new swiping gestures, for example—but it’s still all about screens. To see just how screen-centric the culture of Microsoft is, and how the company imagines the future, watch some of its online videos that present the company’s vision of the future. (You can find links at enchantedobjects.com.) You will see that screens running the Microsoft Surface user interface will be available in every size and shape and customized for every context, from schools to airports to museums and bedrooms. They show palm-size versions, tabloid formats (for traditionalists who still like the idea of a “newspaper”), screens as big as a desk or, better yet, large enough to fill your wall.

This vision of the future can hardly be called a vision at all because it offers nothing new. It just extends the familiar and obvious line forward: same thing, different sizes, different places. For businesses, the Terminal World future is a snap to imagine, the way forward is relatively clear, next-quarter results are falling-off-a-log simple to forecast, and by sticking with it you avoid any disruption to your product-development plans. Your career is safe.

But here’s my gripe with black-slab incrementalism. Screens fall short because they don’t improve our relationship with computing. The interfaces don’t take advantage of the computational resources, which double yearly. The devices are passive, without personality. The machine sits on idle, waiting for your orders. The Terminal World asserts a cold, blue aesthetic into our world, rather than responding to our own. Even the Apple products, celebrated for their hipness, are cold and masculine compared to the materiality of wood, stone, cork, fabric, and the surfaces we choose for our homes and bodies. Few of us long for garments constructed of anodized aluminum with a super-smooth finish.

The Terminal World does not care about enchantment. The smartphone does not have a predecessor in our folklore and fairy tales. There is no magic device I know of whose possessor stares zombielike into it, playing a meaningless game, or texting about nothing. It does not fulfill a deep fundamental human desire in an enchanting way.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

PROSTHETICS: THE NEW BIONIC YOU

TODAY, TWO HUNDRED thousand cyborgs are walking the planet—cybernetic organisms composed of organic and nonorganic parts. You may not notice them as they pass by you because they look like rather ordinary human beings. But these creatures have surgically implanted computers, first developed in the mid-1960s, that connect directly to their brain—more specifically, the auditory nerve in the inner ear. Cochlear implants and the benefit they bring are miraculous. A person born without hearing who receives a cochlear implant can recognize, without lip-reading, 90 percent of all words spoken and 100 percent if they do lip-read. This is the benign, positive, even magical prospect of the second future: prosthetics and wearable technology.

This future has its technological antecedents in the fantastic worlds of comic books and imagination: superhumans and mutants, bionic men and women, the unbelievably powerful and swift and capable. Unlike Terminal World, the prosthetics future for technology does take into account our humanity. Prosthetics amplify our bodies, the power of all of our senses, and the dexterity of our hands. It’s appealing to develop technology that keeps us more or less who we are, only more so. We already have memory, and the technology gives us much, much more of it—fantastic storage and retrieval capacity. A Google-like brain. It’s important for technologists to understand this desire to have superhuman powers and extraordinary abilities, to be able to fly like Aladdin or Peter Pan, to leap tall buildings at a single bound like Superman, or to be able to see through walls and around corners like Peepers, the Marvel mutant with telescopic and X-ray vision.

The critical characteristic of technology-as-prosthetic is that it internalizes computational power. It becomes a part of us, so much so that it is us. It’s not out there, external, captured on a screen, forcing us to do something to activate it. The vision of prosthetics is like the cyborgian man or bionic woman. The Six Million Dollar Man was a popular television show in the 1970s based on the novel Cyborg by Martin Caidin. The hero, former astronaut Steve Austin, has been severely injured in the crash of his flying vehicle. Six million dollars later, Austin has a replacement arm, two new legs, and an eye upgraded with a high-precision zoom lens. He can run as fast as a car and lift enormous weight, and his eye is just as sharp as a magic telescope.

The spin-off show, Bionic Woman, features tennis pro Jaime Sommers. After she is seriously injured in a skydiving accident, Sommers bounces back with better legs, an ability to jump to great heights, and superhearing. Even with these bionic parts, Steve and Jaime look like normal human beings. They are improved versions of themselves, rather than Frankensteins or quasi-robots.

This is the fantasy of the bionic person. We remain fundamentally human, but technology-hacked. We look and behave normally, but we are better able to see, hear, remember, communicate, and defend ourselves than the standard all-human model. No wonder bionic people in fantasy and popular culture typically manifest in such roles as secret agent, explorer, or soldier. They can parachute into any environment, peer through darkness, anticipate every hazard, ford raging rivers, scale daunting cliffs, effortlessly kill (and cook) the next meal, construct a shelter and thrive—all single-handedly. I find this entertaining but also limiting. Wouldn’t it be great to see a bionic person who does something other than spy or fight? I want to see a bionic musician, inventor, architect, or city planner! What might those kinds of cyborgs achieve with their enhanced abilities?

In addition to having enhanced or special powers, many superheroes rely on prosthetics. Superman’s archrival, the mad genius Lex Luthor, wears an exoskeleton that makes him stronger and less vulnerable to injury. In the Batman and Robin stories, Clayface sports an exoskeleton that enables him to melt people. I find this vision of prosthetics particularly unappealing because it doesn’t tap into basic positive human desires such as omniscience and creation. These technologies are tools of violence, revenge, and madness—and they’re also clichéd.

What amplified abilities and superpowers do real people crave today? Noise-cancellation technology to drown out the din of the world so we can concentrate better. The ability to detect free Wi-Fi zones and their bandwidth. A mechanism to turn off the annoying TV at an airport or jam the cell phone signal of a yappy fellow traveler. In a cacophonous world we often don’t want to see and hear more than we already do; rather, we want better filters so we see and hear less or just exactly what we want. We don’t want augmented reality, we want diminished reality. That is the modern version of the ancient wish to have superability to subdue the things that threaten us.

THE HEADS-UP DISPLAY: AUGMENTED VISION

The consumer prosthetic technology of the 1980s and ’90s was auditory, but in this decade we’ll see the visual equivalent of the Sony Walkman and the iPod—the personal heads-up display, or HUD. Today’s HUDs are embedded in glasses or goggles, onto which information is superimposed and appears to float in the air before your eyes, such as with Google Glass, or in a large glass field, such as a car windshield.

A better design of these systems is urgently needed. The HUD in the car, for example, lies directly in the driver’s line of sight. The benefit is that you don’t have to look down at an information display and take your eyes off the road, but the risk is that you get distracted by the info-clutter on the windshield. You hit cognitive overload, lose focus on the road, and fail to react to a deer crossing the highway or a car veering into your lane. The challenge for engineers and designers is to create a HUD that is bright enough to be seen on a sunny day, but not so bright that it overwhelms when driving at night. Carmakers are thinking of HUD as a way to make their products different, to stand out from competitors’. Not only will it display the standard dashboard information—speed, gas consumption, audio selection, and the like—but also information from the Internet. Expect the windshield HUD, which is still expensive, to become standard not only in autos but on many other glass surfaces such as conference-room walls, doors, even bus windows. In military applications, where the information is dense and subsecond performance is critical—and cost is no barrier—a HUD is the standard in aircraft cockpits and weaponry. (With a self-driving car, of course, you won’t need a HUD, just a head-down pillow for you to sleep on. More on that later.)

So what’s the...