![]()

1

LONDON, THE FLOWER OF CITIES ALL

And one man in his time plays many parts . . .

As You Like It, Act 2 Scene 7

When did Shakespeare first visit London, and what was the great city like when he arrived? This journey has been the source of enormous conjecture over the centuries, with writers as diverse as John Aubrey and Samuel Johnson speculating over Shakespeare’s first steps in the city which was to be the making of him. John Aubrey, the old gossip, circulated the myth that Shakespeare was on the run from Stratford-upon-Avon after poaching Sir Thomas Lucy’s deer; Johnson perpetuated the theory that Shakespeare’s first employment was tending the horses outside the Theatre, the Elizabethan equivalent of valet parking. Those murky ‘lost years’ between 1588 and 1592 have inspired as many theories as there are blackberries, of an early career in the law, as a tutor, as a soldier, or travelling overseas.

While it is impossible to establish exactly when Shakespeare arrived in London, we do know what London was like when he reached it, by drawing upon other writers of the day. Let us suppose that, for reasons that will become evident, Shakespeare’s first experience of London was not permanent exile from Stratford but a brief excursion. This mission left a lingering impression of the great city and all that could be achieved in it, the sense of infinite possibility which has drawn millions to London over the centuries. Once having tasted London, Shakespeare had to go back.

Imagine a fine May morning in 1586 and young Will Shakespeare riding into London on a borrowed cob, his for the journey. As a courier, his mission was to deliver a sealed letter, the contents of which he neither knew nor cared about, consumed as he was with the spirit of adventure and the prospect of a day in London.

In an age where social class was strictly defined by dress, Will’s appearance would have marked him out as a countryman, a ‘hempen homespun’1 in a russet jacket faced with red worsted, blue ‘camlet’ or goats’ hair sleeves and a dozen pewter buttons. In his grey hose and stockings, large sloppy breeches and the floppy hat that was all the rage in Stratford but passé in town, Will could not pass for anything but a rustic.2 But this would have been of little consequence to a young man newly arrived in London. Leaving his horse at an inn in Holborn which had been recommended to him, he ventured forth to deliver his letter. Like every visitor to London, he was filled with wonder. To all the Queen’s subjects, London was the city. London stood alone, unique, and any Elizabethan who did not live in London lived in the country. London was the magnet, ‘which draweth unto it all the other parts of the land, and above the rest is most usually frequented with her Majesty’s most royal presence’.3 London was the seat of government, the home of ‘Gloriana’, the most excellent Queen Elizabeth, a city famed for the beauty of its buildings, its infinite riches and such a variety of goods that it was considered the storehouse and market of Europe. Craning his head back to look, glancing around him, awestruck, Will was put in mind of old Dunbar’s salutation, ‘O town of townes, London, thou art the flower of Cities all’.4

By eight o’clock in the morning the streets were already crowded and noisy and the day growing warm. Hammers beat, tubs were hooped, pots clinked, tankards overflowed, and the air was full of street cries, a chorus of men and women whetting the appetite and stirring the blood with calls of ‘Hot pies, hot! Apple pies and mutton pies! Live periwinkles! Hot oatcakes, fresh herrings, hot potatoes!’ An orange girl pranced by offering ‘fine Seville oranges! Fine lemons!’ while another buxom lass proffered ‘Ripe, heartychokes ripe! Medlars fine!’ Should one surfeit on this excess of riches, a quack in a shabby black doctor’s gown, green with age, promised salvation in the form of patent medicines and remedies ‘for any of ye that have corns on your feet or on your toes!’ A chimney sweep, grimy from head to foot, walked by, the whites of his eyes glittering against his coal-black skin. The sweep introduced himself to the mistress of a house with a proposal to ‘Sweep chimney, sweep, mistress, from the bottom to the top, Then shall no soot fall into your porridge pot!’5 Will watched the lady conduct the sweep inside before elbowing his way down the thronging street. As often happens, the scenes struck a chord in his heart. A fragment of poetry darted into his mind, like a sparrow flying through a window into a great hall and out the other side. Like chimney sweepers, come to dust . . . He resolved to remember it for later, when he had time alone to write.

Meanwhile, London was already open for business. The apprentices were busy taking down the shutters and opening the shops, setting up their stalls and preparing for the day’s trading. Passing an open doorway, Will spotted a small boy with a satchel in his hand racing down the stairs, as the boy’s father, standing in the shop, demanded, ‘Are you ready yet? It is eight of the clock! You shall be whipped!’ Then he waved the lad off to school, after telling him to invite the schoolmaster to supper, an invitation which would probably save the boy from a beating for his late arrival.

Walking on down Cheapside, Will watched the schoolboy shamble along. Soon the boy was joined by a companion, another schoolboy, and as an old woman rounded the corner crying, ‘Cherry ripe! Cherry ripe!’ both boys started begging her for fruit. The older lad took his chances and seized a bunch of cherries from her basket, whereupon the old woman leaped forward and boxed his ears. The boys dashed away and vanished into a churchyard, and the school that stood within the mighty bulk of St Paul’s. For a penny, Will climbed to the top of St Paul’s steeple, as far as he could go, for the old wooden spire had gone, incinerated by lightning in 1561. But the steeple provided a magnificent panorama of London, the parks and palaces, the mansions of the merchants and the stinking slums. There were young men hawking in Liverpool Street and the River Thames glittered in the sunlight, white with swans and crammed with innumerable boats and vessels from every corner of the known world, and some unknown realms, too. Across the river on Bankside were the distinctive round shapes of the cockpits and the bear gardens, and in the distance was London Bridge, one of the wonders of the world for its length, strength, beauty and height. Twenty magnificent arches spanned the river, with houses built upon it as high as those on the ground and so close that the gables touched. More like a small town than a thoroughfare, London Bridge carried two hundred businesses jostling for attention above a narrow street choked with horses and carts. And on the southern end of London Bridge, too far away for close scrutiny, Will recalled that the skulls of more than thirty executed traitors were displayed on iron spikes, the heads of noblemen who had been beheaded for treason. The descendants of those men boasted of this strange honour, pointing out their ancestors’ heads and believing that they would be esteemed the more because their antecedents were of such high birth that they could covet the crown, even if they were too weak to attain it and ended up being executed as rebels. An intriguing prospect, that such people could make an honour of a fate which was intended to be a disgrace and set an example.6

View of London Bridge by Cornelius Visscher. Note the traitors’ heads stuck on pikes over the south entrance.

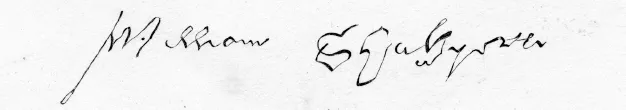

The steeple of St Paul’s contained more names than a parish register. Pausing for a moment, for he was a law-abiding young man, Will added to their number, drawing out his own knife and carving his name upon the leads in what had already become a distinctive signature:

At the bottom of the winding stairs lay St Paul’s Walk, otherwise known as the Mediterranean. Within a minute, Will had been carried along by the bustling crowd, nervous perhaps, as even he would have heard of this den of iniquity. Despite the fact that it was located in the middle of a cathedral, St Paul’s Walk was filled with lowlife exhibiting every aspect of bad behaviour, from jostling and jeering to swearing confrontations and raised fists. Elbow to elbow and toe to toe stood a living tarot of Elizabethan stereotypes, all playing their parts like actors in an endless masquerade. Here were The Knight, The Naïve Gull, The Gallant, The Upstart, The Gentleman, The Clown, The Captain, The Lawyer, The Usurer, The Citizen, The Bankrupt, The Scholar, The Beggar, The Doctor, The Fool, The Ruffian, The Cheater, The Cut-Throat, The Cut-Purse and The Puritan.7 In its noise and spectacle, St Paul’s Walk resembled a map of the world, turning in perfect motion, populated with a vast index of characters, a fascinating place for any writer. A lawyer chattered with his client, merchants discussed their affairs, gallants traded saucy anecdotes and flung back their cloaks to reveal new finery. And all surrounded by potential robbers, cut-purses and conmen. If they had seized Will’s precious letter, they had as good as stabbed him. He had been ordered to guard this document with his life, which was as good as over if his mission failed. Faint with hunger, he elbowed his way out of the crowd in search of dinner.

Outside St Paul’s, the scene was even busier than before. Carts and coaches rattled past, and the streets were thronged with shoals of people, laughing, gossiping, quarrelling, so many men, women and children that it was a wonder the very houses had not been jostled aside under the sheer weight of humanity. As Will stood in a doorway wondering which way to turn, three apprentices in the shop behind him began to sing:

From next door came the sound of the viola da gamba as some good citizen’s daughter took her music lesson. In every doorway, an apprentice called out his master’s wares, every conceivable need from scarves to cabinets, from a rich girdle to a coat hanger. A tradeswoman enticed a grand lady into her shop with promises of ‘fine cobweb lawn, madam, good cambric, fine bone lace’, and two lads approached Will with fine silk stocks and a French hat as he fingered his own rustic hat self-consciously. He held up his hands and backed away as they called after him in unison.

The veritable cornucopia of items to buy was only rivalled by the astonishing variety of sights which surrounded him. On Goldsmiths’ Row, every conceivable character came past and he studied them all, enthralled. Porters staggered under heavy trunks; sober merchants strode past self-importantly in their robes and gold chains; a noisy group of young gallants, resplendent in silk breeches that cost the price of a farm, peacocked along with a cursory ‘by your leave’ as they almost knocked Will into the path of a passing coach. A large crowd gathered by the conduit at the far end of Cheapside, as the Lord Mayor and his aldermen and masters from the twelve livery companies inspected the conduit, upon which the city’s water supply depended. They were mounted on horses and followed by packs of hounds in preparation for a ceremonial hunt which would conclude with the killing of a hare and a fox near St Giles, with ‘a great cry at the death and blowing of horns’.9

But something else had caught Will’s attention by now, something much closer to his heart, for he had seen the brightly coloured signs of the booksellers of St Paul’s swinging from every house. The booksellers’ signs were a library in themselves: the Bible, the Angel, the Holy Ghost, the Bishop’s Head and the Holy Lamb, the Parrot and the Black Boy, the Mermaid and the Ship, Keys and Crowns, the Gun and the Rose and the Blazing Star. Around the churchyard was a menagerie of Green Dragons, Black Bears, White Horses, Pied Bulls, Greyhounds, Foxes and Brazen Serpents. Outside the shops stood trestle tables covered with the booksellers’ wares: volumes fresh from the printer alongside old favourites and the neglected volumes which had never caught on. Booksellers stood in their doorways with their thumbs under their girdles, attempting to catch the eye of a potential buyer with a ‘What lack ye, sir? Come see this new book, lately come forth.’

When one bookseller approached him, Will asked if he had anything by the celebrated author Robert Greene. Invited to step inside, Will hesitated and then shook his head, remembering that he still had to deliver the letter to an address on Fish Street Hill, near London Bridge. This mission was what brought him to London and he could not allow himself to be distracted by the sight of more books than he had ever seen in his life.

When Will eventually found the house on Fish Street Hill, it was to be told that the recipient, Sir Toby Gathercole, was not yet home but was expected soon, for dinner. Gathercole’s apprentice invited Will in to wait, and Will soon fell into conversation with the lively youth who was minding the wine merchant’s premises in his master’s absence. Will had heard tell of the London apprentices; intimidating young men who bellowed and roared, rioted at Whitsuntide, stoned foreigners and handed out a beating to anyone who aggravated them. But this lad, Andrew by name, was approachable, ready to talk about learning his trade but equally ready to moan that his master worked him too hard and he never had a minute to himself. There was no time to go a-Maying, no time for fencing lessons, or dancing classes, or a game of football in the street. Andrew was at his master’s beck and call at every hour of the day and night. Just as Andrew was lamenting the fact that his master did not give him leave to go out into the street to watch a fight yesterday, Sir Toby Gathercole himself returned home, sweating profusely in a flurry of red velvet, remarking on the unseasonable weather and mopping his brow with a silken handkerchief. Will stepped forward nervously, explained his errand and handed over his parchment document with its embossed waxen seal. Gathercole bestowed upon him one penetrating glance from slate-grey eyes, snatched the letter without so much as a word of thanks and disappeared into an inner room. When he emerged some minutes later he was in high good humour, clasped Will upon the shoulder like an old comrade and slyly dropped ten shillings into his palm, before inviting him to join them at their table.

At that point, Mistress Gathercole appeared, flushed and angry, her ample bosom heaving as she rebuked her husband. ‘Fie! Why have you tarried so long at the Exchange? The meat is marred!’

‘Have patience, Maria!’ her husband replied. ‘We have company. Look to the children.’

Will, who had been expecting a ‘shilling ordinary’ or a meagre tavern dinner of bread and cheese, was only too happy to accept Gathercole’s offer, whether the meat was burned or not. The merchant’s four children emerged, their hands and faces freshly scrubbed, and were seated at the board. As soon as Sir Toby had said grace in Latin, the servants laid the dishes before them. Will was impressed: this was good, satisfying fare. At home in the country, meals were simple and meat was scarce, but here it was evident that Sir Toby was a good trencherman. A dish of roast capons was set upon the table, along with a game pie, its pastry topping yellow with spices. Will was offered a glass of charneco, a sweet red wine, and a foaming tankard of ale; there were sweetmeats and quince jellies, a salad of lettuce leaves, and a marchpane or marzipan tart. To round off dinner a dish of gellif, a fruit ice pudding, was borne in to cries of excitement from the children.

Over dinner, talk turned to the Royal Exchange, and the value of the merchants having a building where they could meet, sheltered from the wind and rain. Sir Toby Gathercole extolled the virtues of Sir Thomas Gresham, who founded the Royal Exchange in 1565, telling Will he had been to Venice, and the Rialto was a ‘mere bauble’ compared with the Exchange. Gresham had done much to adorn the City of London and Gathercole felt assured his fame would long outlive him.

When Will expressed an interest in seeing the Royal Exchange, Gathercole offered to take him there that afternoon. As the merchant led Will up Fish Street, he pointed out other places of interest as they passed. Gathercole conducted Will up Gracechurch Street, and at the corner of Cornhill and Leadenhall called his attention to the fine views of houses and gardens as they looked up Bishopsgate. To the left was Gresham’s own house, where Gresham entertained Queen Elizabeth herself at a notable banquet. And there, almost opposite, was Crosby Hall, a splendid mansion built by the wool merchant Sir John Crosby in 1466 ‘and once,’ Sir Toby added with a frisso...