- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

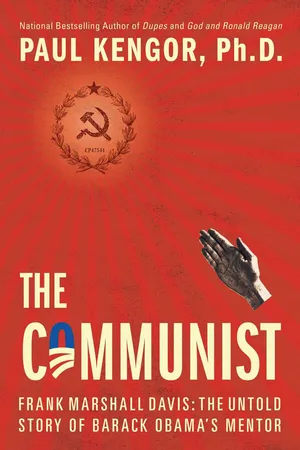

The Communist

About this book

“I admire Russia for wiping out an economic system which permitted a handful of rich to exploit and beat gold from the millions of plain people… As one who believes in freedom and democracy for all, I honor the Red nation.” —FRANK MARSHALL DAVIS, 1947

In his memoir, Barack Obama omits the full name of his mentor, simply calling him “Frank.” Now, the truth is out: Never has a figure as deeply troubling and controversial as Frank Marshall Davis had such an impact on the development of an American president.

Although other radical influences on Obama, from Jeremiah Wright to Bill Ayers, have been scrutinized, the public knows little about Davis, a card-carrying member of the Communist Party USA, cited by the Associated Press as an “important influence” on Obama, one whom he “looked to” not merely for “advice on living” but as a “father” figure.

Aided by access to explosive declassified FBI files, Soviet archives, and Davis’s original newspaper columns, Paul Kengor explores how Obama sought out Davis and how Davis found in Obama an impressionable young man, one susceptible to Davis’s worldview that opposed American policy and traditional values while praising communist regimes. Kengor sees remnants of this worldview in Obama’s early life and even, ultimately, his presidency.

Is Obama working to fulfill the dreams of Frank Marshall Davis? That question has been impossible to answer, since Davis’s writings and relationship with Obama have either been deliberately obscured or dismissed as irrelevant. With Paul Kengor’s The Communist, Americans can finally weigh the evidence and decide for themselves.

In his memoir, Barack Obama omits the full name of his mentor, simply calling him “Frank.” Now, the truth is out: Never has a figure as deeply troubling and controversial as Frank Marshall Davis had such an impact on the development of an American president.

Although other radical influences on Obama, from Jeremiah Wright to Bill Ayers, have been scrutinized, the public knows little about Davis, a card-carrying member of the Communist Party USA, cited by the Associated Press as an “important influence” on Obama, one whom he “looked to” not merely for “advice on living” but as a “father” figure.

Aided by access to explosive declassified FBI files, Soviet archives, and Davis’s original newspaper columns, Paul Kengor explores how Obama sought out Davis and how Davis found in Obama an impressionable young man, one susceptible to Davis’s worldview that opposed American policy and traditional values while praising communist regimes. Kengor sees remnants of this worldview in Obama’s early life and even, ultimately, his presidency.

Is Obama working to fulfill the dreams of Frank Marshall Davis? That question has been impossible to answer, since Davis’s writings and relationship with Obama have either been deliberately obscured or dismissed as irrelevant. With Paul Kengor’s The Communist, Americans can finally weigh the evidence and decide for themselves.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Growing Up Frank

FRANK MARSHALL DAVIS was born on December 31, 1905. He grew up in Arkansas City, Kansas, which he described as a “yawn town fifty miles south of Wichita, five miles north of Oklahoma, and east and west of nowhere worth remembering.”1 That was a charitable description, given the racism he endured in that little town.

In his memoirs, Frank began by taking readers back to his high-school graduation on a “soft night in late spring, 1923.” He was six feet one and 190 pounds at age seventeen, but “I feel more like one foot six; for I am black, and inferiority has been hammered into me at school and in my daily life from home.” He and three other black boys “conspicuously float in this sea of white kids,” the four of them the most blacks ever in one graduating class. “There are no black girls,” wrote Frank. “Who needs a diploma to wash clothes and cook in white kitchens?”2

Frank was rightly indignant at this “hellhole of inferiority.” He said that he and his fellow “Negroes reared in Dixie” were considered “the scum of the nation,” whose high-school education “has prepared us only to exist at a low level within the degrading status quo.” And even the education they acquired was often belittling. “My white classmates and I learned from our textbooks that my ancestors were naked savages,” said Frank, “exposed for the first time to uplifting civilization when slave traders brought them from the jungles of Africa to America. Had not their kindly white masters granted these primitive heathens the chance to save their souls by becoming Christians?”3

Frank would one day rise above the degrading status quo. For now, he lamented that he himself had fallen victim to this “brainwashing,” and “ran spiritually with the racist white herd, a pitiful black tag-a-long.”4

As Frank surveyed the sea of white classmates that soft spring evening, he was glad to know it would be the last time he would be with them. He could think of only three or four white boys who had treated him as an equal and a friend, and whom he cared to remember.5

One moment that was unforgettably seared into his soul was an incident when he was five years old. An innocent boy, Frank was walking home across a vacant lot when two third-grade thugs jumped him, tossed him to the ground, and slipped a noose over his neck. He kicked and screamed as the two devils prepared, in Frank’s words, “their own junior necktie party.” They were trying to lynch little Frank Marshall Davis.6

As the noose tightened, a white man heroically appeared, chasing away the two savages, freeing Frank, brushing the dirt from his clothes. He walked little Frank nearly a mile home, then simply turned around and went about his business. Frank never learned the man’s identity.7

Imagine if that kindly man could have known that that “Negro” boy he shepherded home would one day help mentor the first black president of the United States. It is a moving thought, one that cannot help but elicit the most heartfelt sympathy for Frank, even in the face of his later political transgressions.

Frank’s parents apparently informed the school of the attempted lynching, but school officials did not bother. “I was still alive and unharmed, wasn’t I?” scoffed Frank. “Besides, I was black.”

Frank rose above the jackboot of this repression, assuring the world that this was one young black man who would not be tied down. He enrolled in college, first attending Friends University in Wichita, before transferring to Kansas State University in Manhattan.8 At Kansas State from 1924 to 1926, Frank majored in journalism and practiced writing poetry, impressing students and faculty alike.

These colleagues were almost universally white. To their credit, some of them saw in Frank a writing talent and were eager to help.

RACISM

Of course, that upturn did not end the racism in Frank’s life. Another ugly incident occurred in a return home during college break.9

A promising young man, Frank was working at a pool hall, trying to save money to put himself through school. It was midnight, and he was walking home alone. A black sedan slowly approached him. Out of the lowered window came a redneck voice: “Where’n hell you goin’ this time of night?”

Frank warily glanced over and saw two white men in the front seat and another in the back. Worried, he asked why it was their business.

“Don’t get smart, boy. We’re police,” snapped one of them, flashing a badge slightly above his holstered pistol. “I’m police chief here. Now, what th’ hell you doing in this neighborhood this time of night?”

A frightened Frank explained that this was his neighborhood. He had lived there for years, was home on college break, and was simply walking home from work.

“Yeah?” barked the chief. “Well, you git your black ass in the car with us. A white lady on th’ next street over phoned there was somebody prowling around her yard.”

Frank asked, “Am I supposed to fit the description?”

The chief found Frank’s question haughty: “Shut up an’ git in the car!”

They delivered Frank to the woman’s doorstep. “Ain’t this him?” said the hopeful chief.

The woman quickly said it was not. Frank looked nothing at all like the man she had spotted.

“Are you sure?” pushed the chief. “Maybe you made a mistake.”

The lady insisted that Frank was not the suspect, to the lawman’s great disappointment.

Frank suspected that the chief was keenly disappointed not to have the opportunity to work him over. “It wasn’t everyday they had a chance to whip a big black nigger,” said Frank, “and a college nigger at that.”

The chief told Frank to get back in the car, where he began interrogating him again, even though Frank was fully exonerated. The chief was not relenting. He was looking for blood.

“Where do you live?” the chief continued. Frank stated his address. The chief turned to his buddies: “I didn’t know any damn niggers lived in this part of town, did you?” One of the officers replied: “There’s a darky family livin’ down here somewhere.”

Frank was utterly helpless, at the mercy of men with badges and guns and “the law” behind them. He boiled inside, but could do nothing. He later wrote: “At that moment I would have given twenty years off my life had I been able to bind all three together, throw them motionless on the ground in front of me, and for a whole hour piss in their faces.”

RESENTMENT

Frank escaped this incident physically unharmed, released to his home by the police. But he was hardly unscathed. Such injustice understandably fueled a lifelong resentment.

Frank’s upbringing, as told through his memoirs, is gripping. His writing is witty, engaging, sarcastic, at times delightful, leaving it hard not to like Frank, or at least be entertained by him. But the wonderful passages are tempered by Frank’s numerous ethnic slurs, mostly aimed in a self-deprecating manner at himself and his people, but also directed at others, such as “the Spanish Jew” (never named) whose restaurant he frequented in Atlanta, and, worst of all, by the many sexually explicit passages. One can see in Frank’s memoirs the author of Sex Rebel, and one can see a lot of sexism, with Frank making constant graphic references to women’s private parts (with vulgar slang terms) and referring to women as everything from “white chicks” to “a jane” to a “luscious ripened plum,” just for starters.10 In his memoirs, Frank devoted an inordinate amount of space to his sexual encounters. Sex Rebel must have been his chance to more fully indulge his lurid obsessions.

• • •

Of course, Frank also invested his writing talent in noble purposes: advancing civil rights by chronicling the persecutions of a black man. Interestingly, to that end, Frank’s memoirs are remarkably similar to Barack Obama’s memoirs; the running thread being the racial struggles of a young black man in America.

Frank’s memoirs reveal an often bitter man, one who had suffered the spear of racial persecution. His contempt for his culture and society also led to a low view of America. When America is acknowledged in his memoirs, it is not a pretty portrait: “The United States was the only slaveholding nation in the New World that completely dehumanized Africans by considering them as chattel, placing them in the same category as horses, cattle, and furniture.” That attitude, wrote Frank, was still held by too many American whites.11 Thus, his hometown of Arkansas City was “no better or worse than a thousand other places under the Stars and Stripes.”12

Again, that bitterness is understandable, a toxic by-product of the evil doings of Frank’s tormentors. Yet what is unfortunate about Frank’s narrative is the lack of concession, smothered (as it was) by resentment, that this same America, no matter the sins of its children, still provided the freedom for Frank to pull himself up and achieve remarkable things, which are manifest as one reads his memoirs.

We also find in those memoirs a resentfulness of religion and God. Frank had been raised by Baptist parents and taught the power of prayer “from infancy.” But he felt he did not see results. When blacks were massacred in riots in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Frank knelt at his bedside and “prayed for retribution.” When nothing happened to the perpetrators (at least in this world), he was puzzled. The results were the same when a young black mother in the South was burned at the stake while the white mob laughed at her cries. Frank again prayed for divine retribution. “I became deeply depressed,” said Frank, “feeling that God had somehow let me down.”13

Frank was also angry at how every picture he had seen portrayed a white Jesus, “usually blonde,” and a blackened devil. If this was so, pondered the young Frank, what could he expect as a black man? He asked himself: Why would a “white Lord” punish his own white, ethnic brothers?14

For Frank, this childlike misinterpretation was “tiny at first” but snowballed. He suspected that the Christian religion was a “device” to keep blacks subservient to whites. “Very well,” scoffed Frank. “Then I was through with it.”15

To the contrary, Frank’s black contemporaries, and the generation of slaves who recently preceded them, understood the culprit not as God but as men, not a bad Christian religion but bad Christians. Professor Gary Smith, author of an Oxford University Press book on views of heaven, states that black slaves viewed heaven as “the very negation of slavery,” a place where they would finally experience the dignity and worth denied on earth. “Admission to heaven would validate their humanity,” writes Smith. “Although masters and many other whites defined them as uncivilized brutes or mere commodities, in God’s eyes they were valuable, precious human beings for whom His Son died.” Smith adds that “many blacks looked forward to heavenly bliss and compensation and divine retribution for their suffering.”16

There was more to Frank’s rejection of God. His grandfather was agnostic, and those seeds, when mixed with Frank’s unanswered prayers for retribution, “fell in welcoming soil.” (As a parallel to Barack Obama, Newsweek described Obama’s grandfather as a “lapsed Christian” who likewise did not...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Description

- About Paul Kengor

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Introduction: Past Is Prologue

- Chapter 1: Growing Up Frank

- Chapter 2: Atlanta, 1931–32: The Communists Swarm to Scottsboro

- Chapter 3: Frank’s Work for the Atlanta Daily World (1931–34)

- Chapter 4: Paul Robeson and Progressive Dupes

- Chapter 5: Back to Chicago: “Peace” Mobilization and Duping the “Social Justice” Religious Left

- Chapter 6: War Time and Party Time (1943–45): Frank with CPUSA and the Associated Negro Press

- Chapter 7: The Latter 1940s: Frank and the Chicago Crew

- Chapter 8: The Chicago Star

- Chapter 9: Frank’s Writings in the Chicago Star (1946–48)

- Chapter 10: Frank Heads to Hawaii

- Chapter 11: Frank in the Honolulu Record (1949–50): Target, Harry Truman

- Chapter 12: Frank in the Honolulu Record (1949–50): Other Targets, from “HUAC” to “Profits” to GM

- Chapter 13: Frank and the Founders

- Chapter 14: 1951–57: Frank on Red China, Korea, Vietnam, and More

- Chapter 15: Mr. Davis Goes to Washington

- Chapter 16: Frank versus “the Gestapo”

- Chapter 17: American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born

- Chapter 18: When Frank Met Obama

- Chapter 19: When Obama Leaves Frank: Occidental College

- Chapter 20: Frank Re-Emerges—and the Media Ignore Him

- Chapter 21: Conclusion: Echoes of Frank

- Motivation and Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Frank Marshall Davis Documents

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Communist by Paul Kengor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.