eBook - ePub

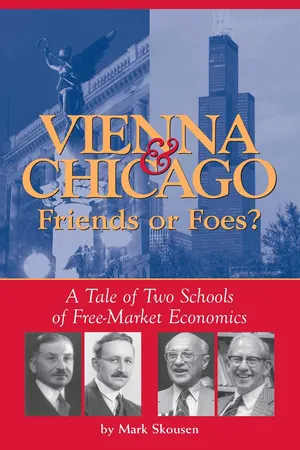

Vienna & Chicago, Friends or Foes?

A Tale of Two Schools of Free-Market Economics

This is a test

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Is the bridge between the Austrian and Chicago schools coming together or moving apart?In Vienna and Chicago, Friends or Foes? economist and author Mark Skousen debates the Austrian and Chicago schools of free-market economics, which differ in monetary policy, business cycle, government policy, and methodology. Both have played a successful role in advancing classic free-market economics and countering the critics of capitalism during crucial times and the battle of ideas. But, which of the two is correct in its theories?

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Vienna & Chicago, Friends or Foes? by Mark Skousen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economía & Teoría económica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomíaSubtopic

Teoría económicaChapter One

INTRODUCTION

VIENNA AND CHICAGO, A TALE OF TWO SCHOOLS

Yet the award [the 1974 Nobel Prize in Economics] documented the beginning of a great shift toward … a renewed belief in the superiority of markets…the eventual victory of this viewpoint was really a tale of two cities—Vienna and Chicago.

—Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw (1998:96)

In late September, 1994, Henri Lepage asked me to address the Mont Pelerin Society in Cannes, France. The title was “I Like Hayek,” an appreciation of the principal founder of the Society in 1947. I thought the subject would be well received, but I was mistaken. Over a dozen attendees lined up to take issue with my favorable comments about Hayek’s capital theory and macroeconomic model of inflation and business cycles. It turned out that the critics were followers of Milton Friedman and the Chicago school.

Anyone who has ever attended a Mont Pelerin Society meeting will quickly attest that this international group of freedom-fighters are divided into two camps: followers of the Austrian school and followers of the Chicago school. I say “divided” guardedly because these two camps undoubtedly have more in common than disagreement. In general, they are devout believers in free markets and free minds. Yet they seem to relish the rivalry that exists regarding fundamental issues of methodology, money, business cycles, government policy, and even who are the great economists.

The first group is known as the Austrian or Vienna school, founded by Carl Menger, who taught economics at the University of Vienna in the late 19th century. Menger’s disciples, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, left Vienna during the Nazi era and established an Austrian following in England and the United States. In 1974, a year after Mises died, Hayek received the Nobel Prize in Economics, the first one given to a free-market economist.

It was a long battle toward recognition. In 1947, Hayek invited a small group of classical liberals from around the world to a conference at the Hotel du Parc on the slopes of Mont Pelerin, Switzerland. Hayek was alarmed by the rapid advance of socialism in the post-war era, and decided to establish a society aimed at preserving a free civilization and opposed to all forms of totalitarianism. He dedicated the meeting in the spirit of Adam Smith and his “system of natural liberty.” Among the 38 participants were the Austrians Ludwig von Mises, Fritz Machlup, and Karl Brandt. It also included the Americans Milton Friedman and George Stigler, who would become leaders of the market-oriented economics department at the University of Chicago. The quasi-market tradition at Chicago actually began earlier with the works of Frank H. Knight, Henry Simons and Jacob Viner. Friedman and Stigler were the second generation of free-market economists at Chicago. Both went on to win the Nobel Prize (Friedman in 1976, Stigler in 1982). Milton Friedman in particular has so dominated the department that Friedmanite economics has become practically synonymous with the Chicago or monetarist school. His prestige is felt on the campus even today, a generation after his retirement. The Chicago school has continued to have enormous influence, both in the United States and around the world. Friedman is considered one of the most eminent economists living today.

Points of Common Ground

As members of a free-market association, how could these two camps disagree so vehemently? The reality is that they don’t disagree on most issues. Generally speaking, members of the Austrian and Chicago schools have much in common and, in many ways, could be considered intellectual descendants of laissez faire economics of Adam Smith, philosophical cousins rather than foes.1

•Both champion the sanctity of private property as the basis of exchange, justice, and progress in society.

•Both defend laissez-faire capitalism and believe firmly in Adam Smith’s invisible hand doctrine, that self-motivated actions of private individuals maximize happiness and society’s well-being, and that liberty and order are ultimately harmonious (Barry 1987:19, 29, 193).

•Both are critics of Marx and the Marxist doctrines of alienation, exploitation, and other anti-capitalist notions.

•Both support free trade, a liberalized immigration policy, and globalization.

•Both generally favor open borders for capital and consumer goods, labor, and money.

•Both oppose controls on exchange, prices, rents, and wages, including minimum wage legislation.

•Both believe in limiting government to defense of the nation, individual property, and selective public works (although a few in both camps are anarchists, such as Murray Rothbard and David Friedman).

•Both favor privatization, denationalization, and deregulation.

•Both oppose corporate welfarism and special privileges (known as rent seeking or privilege seeking).

•Both reject socialistic central planning and totalitarianism.

•Both believe that poverty is debilitating but that natural inequality is inevitable, and they defend the right of all individuals, rich or poor, to keep, use and exchange property (assuming it was justly acquired). They do not join the chorus of pundits bashing the rich, although they frequently condemn corporate welfarism.

•Both refute the Keynesian and Marxist interventionists who believe that market capitalism is inherently unstable and requires big government to stabilize the economy.

•Both are generally opposed to deficit spending, progressive taxation, and the welfare state, and favor free-market alternatives to Social Security and Medicare.

•Both favor market and property-rights solutions to pollution and other environmental problems, and in general consider the environmentalist crisis as overblown.

Israel Kirzner rightly concludes, “It is important not to exaggerate the differences between the two streams..…there is an almost surprising coincidence between their views on most important policy questions.…both have basically the same sound understanding of how a market operates, and this is responsible for the healthy respect which both approaches share in common for its achievements” (Kirzner 1967:102).

Speaking of achievements, both can claim separate victories in the battle of ideas during the past two centuries: the Austrian school for introducing the subjective Marginalist Revolution in the late 19th century, and then dissecting the inevitable collapse of the Marxist/socialist central planning paradigm in the 20th century; and the Chicago school for mounting a successful counterrevolution to Keynesian macroeconomics and the “imperfect” or monopolistic competition model in microeconomics. Members of both schools have won Nobel prizes in economics, although the Chicago school has a clear lead. And both have sometimes been viciously attacked by their opponents, including Keynesians, Marxists, and institutionalists.

It is the thesis of this book that both the Austrian and Chicago schools played significant and largely successful roles in correcting the errors of classical economics and countering the critics of capitalism — socialists, Marxists, Keynesians, and institutionalists — during crucial times in the battle of ideas and events. The early chapters outline the focal points in history where the Austrian and Chicago economists played major roles in defending and advancing Adam Smith’s system of natural liberty. Without their vital place, world history may well have been vastly different, and not for the better.

Then Come the Disagreements

Yet with so much to celebrate, where do they disagree? Surprisingly, on quite a few points. While they may be considered followers of Adam Smith’s invisible hand of laissez faire, the descendants are divided into two wings of free-market economics. The Austrians and the Chicagoans differ in four broad categories:

First, methodology. The Austrians, following the writings of Ludwig von Mises, favor a deductive, subjective, qualitative, and market-process approach to economic analysis. The Chicagoans, following the works of Milton Friedman, prefer historical, quantitative, and equilibrating analysis. Friedman and his followers demand empirical testing of theories and, if the results contradict the theory, the theory is rejected or reformed. Mises denies this historical approach in favor of extreme apriorism. According to Mises as well as his disciples Murray Rothbard and Israel Kirzner, economics should be built upon self-evident axioms, and history (empirical data) cannot prove or disprove any theory, only illustrate it, and even then with some suspicion.

Second, the proper role of government in a market economy. How pervasive are externalities, public goods, monopoly, imperfect competition, and macroeconomic stability in the market economy, and what how much government is necessary to handle “market failure”? The Austrians have consistently supported laissez faire policies while the Chicago school has shifted gears over the years. (One might say that both are “anti-statist” but the Austrians are more “anti-statist.”) Is Adam Smith’s system of natural liberty sufficiently strong to break up monopolies through powerful competitors, or is government necessary to impose antitrust policies when appropriate? The Austrians have always favored a naturalist, non-interventionist approach. On the other hand, the first Chicago school, led by Henry Simons, took a strong interventionist view, favoring the break-up of large utilities and other natural monopolies. The second generation at Chicago, led by George Stigler, initially supported Simons’ interventionism, but ultimately reversed course in favor of a Smithian belief in the power of competition and non-interventionism.

According to Israel Kirzner, Peter Boettke and other Austrians, the difference between the two schools is even more fundamental: the Chicago school employs an “equilibrium always” pure competition model (what Chicago economists call an “as if” competition model) that assumes costless perfect information and the Austrians employ a more dynamic “disequilibrium” process model of market capitalism that takes into account institutions and decentralized decision making (Kirzner 1997, Boettke 1997). The debate over the most appropriate competitive model also spills over into issues of political economy, public choice, law and economics, and the efficiency of democracy.

Third, sound money. What is the ideal monetary standard? Both schools favor a stable monetary system, but they differ markedly on the means. Most Austrians prefer a gold standard, or more generally, a naturally-based commodity standard created by the marketplace. Some go further and demand “free banking,” a competitive system whereby private banks issue their own currency, checking accounts and credit services with a minimum of government regulation. The Chicago school, on the other hand, rejects the gold standard in favor of an irredeemable money system, where the money supply increases at a steady or neutral rate (the monetarist rule). Both ideally desire 100% reserves on demand deposits as a stabilizing mechanism, though here again, there is a difference—the Austrians want demand deposits backed by gold or other suitable commodity, the Chicagoans by fiat money.

Fourth, the business cycle, capital theory, and macroeconomics. Mises and Hayek developed the “Austrian” theory of the business cycle, maintaining that expanding the fiat money supply and artificially lowering interest rates create an unsustainable, unstable boom that must eventually collapse. Friedman and his colleagues reject most aspects of the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle in favor of an aggregate monetary model. The Chicagoans praise ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. Introduction: A Tale of Two Schools

- Chapter 2. Old and New Vienna: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of the Austrian School

- Chapter 3. The Imperialist Chicago School

- Chapter 4. Methodenstreit: Should a Theory be Empirically Tested?

- Chapter 5. Gold vs. Fiat Money: What is the Ideal Monetary Standard?

- Chapter 6. Macroeconomics, the Great Depression, and the Business Cycle

- Chapter 7. Antitrust, Public Choice and Political Economy: What is the Proper Role of Government?

- Chapter 8. Who Are the Great Economists?

- Chapter 9. Faith and Reason in Capitalism

- Chapter 10. The Future of Free-Market Economics: How Far is Vienna from Chicago?

- Index

- About the Author