- 629 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

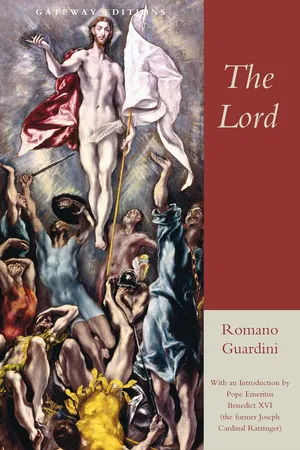

The Lord

About this book

The only true and unedited telling of the life of Christ—his life and times, in historical context, but not lacking the psychology behind his physical being and spirit. Unlike other books seeking to strip Jesus' story to reveal only the human being, Romano Guardini's The Lord gives the complete story of Jesus Christ—as man, Holy Ghost, and Creator. Pope Benedict XVI lauds Guardini's work as providing a full understanding of the Son of God, away from the prejudice that rationality engenders. Put long-held myths aside and discover the entire truth about God's only begotten Son.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

The Beginnings

dp n="20" folio="" ?dp n="21" folio="" ? I

ORIGIN AND ANCESTRY

If someone in Capharnaum or Jerusalem at the time had asked the Lord: Who are you? Who are your parents? To what house do you belong?—he might have answered in the words of St. John’s gospel: “Amen, amen, I say to you, before Abraham came to be, I am” (8:58). Or he might have pointed out that he was “of the house and family of David” (Luke 2:4). How do the Evangelists begin their records of the life of Jesus of Nazareth who is Christ, the Anointed One?

John probes the mystery of God’s existence for Jesus’ origin. His gospel opens:

In the beginning was the Word,

and the Word was with God;

and the Word was God.

He was in the beginning with God.

All things were made through him,

and without him was made

nothing that has been made. . . .

He was in the world,

and the world was made through him,

and the world knew him not. . . .

And the Word was made flesh,

and dwelt among us.

And we saw his glory—

glory as of the only-begotten of the Father—

full of grace and truth. . . .

(JOHN 1:1–14).

Revelation shows that the merely unitarian God found in post-Christian Judaism, in Islam, and throughout the modern consciousness does not exist. At the heart of that mystery which the Church expresses in her teaching of the trinity of persons in the unity of life stands the God of Revelation. Here John seeks the root of Christ’s existence: in the second of the Most Holy Persons; the Word (Logos), in whom God the Speaker, reveals the fullness of his being. Speaker and Spoken, however, incline towards each other and are one in the love of the Holy Spirit. The Second ‘Countenance’ of God, here called Word, is also named Son, since he who speaks the Word is known as Father. In the Lord’s farewell address, the Holy Spirit is given the promising names of Consoler, Sustainer, for he will see to it that the brothers and sisters in Christ are not left orphans by his death. Through the Holy Spirit the Redeemer came to us, straight from the heart of the Heavenly Father.

Son of God become man—not only descended to inhabit a human frame, but ‘become’ man—literally; and in order that no possible doubt arise, (that, for example, it might never be asserted that Christ, despising the lowliness of the body, had united himself only with the essence of a holy soul or with an exalted spirit,) John specifies sharply: Christ “was made flesh.”

Only in the flesh, not in the bare spirit, can destiny and history come into being; this is a fact to which we shall often return. God descended to us in the person of the Savior, Redeemer, in order to have a destiny, to become history. Through the Incarnation, the founder of the new history stepped into our midst. With his coming, all that had been before fell into its historical place “before the birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” anticipating or preparing for that hour; all that was to be, faced the fundamental choice between acceptance and rejection of the Incarnation. He “dwelt among us,” “pitched his tent among us,” as one translation words it. “Tent” of the Logos—what is this but Christ’s body: God’s holy pavilion among men, the original tabernacle of the Lord in our Midst, the “temple” Jesus meant when he said to the Pharisees: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (John 2:19). Somewhere between that eternal beginning and the temporal life in the flesh lies the mystery of the Incarnation. St. John presents it austerely, swinging its full metaphysical weight. Nothing here of the wealth of lovely characterization and intimate detail that makes St. Luke’s account bloom so richly. Everything is concentrated on the ultimate, all-powerful essentials: Logos, flesh, step into the world; the eternal origin, the tangible earthly reality, the mystery of unity.

Quite different the treatment of Christ’s origin in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. St. Mark does not mention the Incarnation. His first eight verses are concerned with the Forerunner; then immediately: “And it came to pass in those days, that Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan” (Mark 1:9). Matthew and Luke, on the other hand, painstakingly trace Jesus’ genealogy, the course taken by his blood through history.

In Matthew this line of descent opens the gospel. It begins with Abraham and leads via David and the succession of the Judean kings through Joseph “the husband of Mary” (Matt. 1:16). In Luke the genealogy is to be found in the third chapter after the account of Jesus’ baptism: “And Jesus himself, being—as was supposed—the son of Joseph,” whose line reaches back through Heli, Mathat, Levi through names about which we know nothing but their sound; back to David; then through his forbears to Juda, Jacob, Isaac and Abraham, who in turn are linked with the spiritual giants of prehistoric ages—Noah, Lamech, Henoch, and finally through Adam, to God (Luke 3:23–38).

It is often asked how two such different genealogies came to be recorded. Some scholars consider the first the lineage of the law, that is of Joseph, who counted legally as Jesus’ father. The other genealogy, then, would be that of the blood, of Mary. Since according to Old Testament law, no line could continue through a woman, Joseph’s line was substituted. A third theory is that of the levirate marriage required of an unmarried man to his brother’s widow if that brother died childless. The first issue of such a union belonged to the line of the deceased, while subsequent children continued the genealogy of the natural father. Because of these different approaches to the question, Jesus’ ancestry was recorded variously.

It is very possible that this last explanation is the correct one, especially since it is Mary’s line that is recorded by St. Luke, the Evangelist who brings the Mother of the Lord particularly close to us.

Study of the genealogies makes one thoughtful. Aside from the dignity lent them by the word of God, they possess per se a high degree of probability, for the ancient races had a very true memory. Moreover, the recorded lineage of the nobility was preserved in the temple archives. We know, for example, that Herod, the nameless upstart, had such records destroyed because he wished to curtail the pride of the old families by depriving them of the possibility of comparing their background with his.

How their names sing! From them, during long dark centuries, emerge the great figures of the morning of time: Adam, word still heavy with nostalgia for a lost paradise; Seth, born to him after Cain’s murder of Abel; Henoch, who walked with God and was said to have been spirited away by him. Then comes Methusalah, old as the mountains; and Noah, encompassed by the terrible roaring of the flood. One after another they appear, milestones on the road through the millenia leading from Paradise to him whom God called from his home and people to enter into his covenant: Abraham, who “believed” and was a “friend of God”; Isaac, the son given him by a miracle and returned to him at the altar; Jacob, the grandchild who wrestled with the angel of the Lord. These powerful figures personify the strongest element of the Old Testament: that wonderful ability to stand firmly implanted in earthly existence, yet to wander under the eyes of God. They are solidly realistic, these men, bound to all the things of earth; yet God is so close to them, his stamp so indelible on all they are and say, on their good deeds and bad, that their histories are genuine revelations.

Jacob’s son Juda continues the line through Phares and Aram to King David. With David begins the nation’s proudest era—interminable wars at first, then long years of glorious peace under Solomon. But already towards the end of Solomon’s life the royal house turns faithless. Then down plunges its course, deeper and deeper into the dark. Occasionally it reascends briefly, then it continues downhill through war and famine, crime and atrocity, to the destruction of the empire and the transfer to Babylon. There the radiance of the house is utterly extinguished. From now on, the strain barely manages to survive, its descendants muddling through darkness and need. Joseph, Mary’s husband, is an artisan and so poor that for the traditional presentation offering of a lamb, he can afford only two young pigeons, the poor man’s substitute (Luke 2:24).

The history of God’s people emanates from these names, not only from those listed, but also from those conspicuously absent: Achab and his two followers, struck from the files, we are told, because of the curse that the prophet put upon them. Some names leave us strangely pensive. They are names of women, mentioned only in brief asides and included, so some commentators explain, to stop the mouths of those Jews whose attacks were directed against the Mother of God; they should reflect on the dishonor of their royal house, rather than attempt to discredit Mary’s honor.

David’s grandmother, Ruth, does not belong in this company. To the juridically minded Jews, she as a Moabite was a blemish on the royal escutcheon; hadn’t David’s veins received from her the taint of foreign (forbidden) blood? Yet to those of us who know her through the little book that bears her name, she seems very near. On the other hand, it is recorded that Juda, Jacob’s eldest son, begot Phares and Zara with Thamar, his own daughter-in-law. Originally the wife of his eldest son, who died early, she was then, in accordance with the law, wedded to Onan, brother of the deceased, against his will. Onan angered God by withholding Thamar’s marital rights, and therefore had to die. Juda refused the woman his third son, fearing to lose him too. So one day when Juda set out for the sheep-sheering, Thamar donned the raiment of a harlot and waylaid her father-in-law at the lonely crossroads. Twins, Phares and Zara, were their offspring; Phares continued the line (Gen. 38).

As for Solomon, it is recorded that he begot Booz with Rahab, the “mistress of an inn” or “harlot” (in the Old Testament the terms are interchangeable) who received Joshua’s spies in Jericho (Joshua 2). King David begot Solomon with “the wife of Urias.” David was a kingly man. The shimmer of his high calling had lain upon him from earliest childhood; poet and prophet, he was filled with the spirit of God. In long wars he had established the foundations of Israel’s empire. His were the virtues and passions of the warrior: he was magnanimous, but he could also be adamant; even merciless when he thought it necessary. The name of Bethsabee recalls a very black spot on David’s honor. She was the wife of Urias the Hethite, one of David’s officers and a loyal and valiant man. While Urias was away at war, David dishonored this marriage. Urias returned home to report on the battle raging about the city of Rabba; the king, suddenly afraid, attempted to conceal his deed by far from kingly subterfuges. When these failed, he sent Urias back to the war with a letter: “Set ye Urias in the front of the battle, where the fight is strongest: and leave ye him, that he may be wounded and die” (2 Kings 11:15). So it occurred, and David took “the wife of Urias” for his own. When Nathan the prophet revealed God’s wrath to him, David was stricken and repented with prayer and fasting. Nevertheless, he had to watch the child of his sin die. Then David arose, dined and went in to Bethsabee. Solomon was their son (II Kings 11 and 12).

St. Paul says of the Lord: “For we have not a high priest who cannot have compassion on our infirmities, but one tried as we are in all things except sin” (Hebr. 4:15). He entered fully into everything that humanity stands for—and the names in the ancient genealogies suggest what it means to enter into human history with its burden of fate and sin. Jesus of Nazareth spared himself nothing.

dp n="27" folio="9" ?In the long quiet years in Nazareth, he may well have pondered these names. Deeply he must have felt what history is, the greatness of it, the power, confusion, wretchedness, darkness, and evil underlying even his own existence and pressing him from all sides to receive it into his heart that he might answer for it at the feet of God.

dp n="28" folio="10" ? II

THE MOTHER

Anyone who would understand the nature of a tree, should examine the earth that encloses its roots, the soil from which its sap climbs into branch, blossom, and fruit. Similarly to understand the person of Jesus Christ, one would do well to look to the soil that brought him forth: Mary, his mother.

We are told that she was of royal descent. Every individual is, in himself, unique. His inherited or environmental traits are relevant only up to a certain point; they do not reach into the essence of his being, where he stands stripped and alone before himself and God. Here Why and Wherefore cease to exist: neither “Jew nor Greek,” “slave nor freeman” (Gal. 3:27–28). Nevertheless, the ultimate greatness of every man, woman, and child, even the simplest, depends on the nobility of his nature, and this is due largely to his descent.

Mary’s response to the message of the angel was queenly. In that moment she was confronted with something of unprecedented magnitude, something that exacted a trust in God reaching into a darkness far beyond human comprehension. And she gave her answer simply, utterly unconscious of the greatness of her act. A large measure of that greatness was certainly the heritage of her blood.

From that instant until her death, Mary’s destiny was shaped by that of her child. This is soon evident in the grief that steps between herself and her betrothed; in the journey to Bethlehem; the birth in danger and poverty; the sudden break from the protection of her home and the flight to a strange country with all the rigors of exile—until at last she is permitted to return to Nazareth.

dp n="29" folio="11" ?It is not until much later—when her twelve-year-old son remains behind in the temple, to be found after an agony of seeking—that the divine ‘otherness’ of that which stands at the center of her existence is revealed (Luke 2:41–50). To the certainly understandable reproach: “Son, why hast thou done so to us? Behold, in sorrow thy father and I have been seeking thee,” the boy replies, “How is it that you sought me? Did you not know that I must be about my Father’s business?” In that hour Mary must have begun to comprehend Simeon’s prophecy: “And thy own soul a sword shall pierce” (Luke 2:35). For what but the sword of God can it mean when a child in such a moment answers his disturbed mother with an amazed: “How is it that you sought me?” We are not surprised to read further down the page: “And they did not understand the word that he spoke to them.” Then directly: “And his mother kept all these things carefully in her heart.” Not understanding, she buries the words like precious seed within her. The incident is typical: the mother’s vision is unequal to that of her son, but her heart, like chosen ground, is deep enough to sustain the highest tree.

Eighteen years of silence follow. Not a word in the sacred records, save that the boy “went down with them” and “advanced” in wisdom, years and grace “before God and men.” Eighteen years of silence passing through this heart—yet to the attentive ear, the silence of the gospels speaks powerfully. Deep, still eventfulness enveloped in the silent love of this holiest of mothers.

Then Jesus leaves his home to shoulder his mission. Still Mary is near him; at the wedding feast at Cana, for instance, with its last gesture of maternal direction and care (John 2:1–11). Later, disturbed by wild rumors circulating in Nazareth, she leaves everything and goes to him, stands fearfully outside the door (Mark 3:21, and 31–35). And at the last she is with him, under the cross to the end (John 19:25).

From the first hour to the last, Jesus’ life is enfolded in the nearness of his mother. The strongest part of their relationship is her silence. Nevertheless, if we accept the words Jesus speaks to her simply as they arise from each situation, it seems almost invariably as if a cleft gaped between him and her. Take the incident in the temple of Jerusalem. He was, after all, only a child when he stayed behind without a word, at a time when the city was overflowing with pilgrims of all nationalities, and when not only accidents but every kind of violence was to be expected. Surely they had a right to ask why he had acted as he did. Yet his reply expresses only amazement. No wonder they failed to understand!

It is the same with the wedding feast at Cana in Galilee. He is seated at table with the wedding party, apparently poor people, who haven’t much to offer. They run out of wine, and everyone feels the growing embarrassment. Pleadingly, Mary turns to her son: “They have no wine.”

But he replies only: “What wouldst thou have me do, woman? My hour has not yet come.” In other words, I must wait for my hour; from minute to minute I must obey the voice of my Father—no other. Directly he does save the situation, but only because suddenly (the unexpected, often instantaneous manner in which God’s commands are made known to the prophets may help us to grasp what happens here) his hour has come (John 2:1–11). Another time, Mary comes down from Galilee to see him: “Behold, thy mother and thy brethren are outside, seeking thee.” He answered, “Who are my mother and my brethren? Whoever does the will of God, he is my brother and sister and mother” (Mark 3:32–35). And though certainly he went out to her and received her with love, the words remain, and we feel the shock of his reply and sense something of the unspeakable remoteness in which he lived.

Even his reply to the words, “Blessed is the womb that bore thee,” sometimes interpreted as an expression of nearness could also mean distance: “Rather, blessed are they who hear the word of God and keep it.”

Finally on Calvary, his mother under the cross, thirsting for a word, her heart crucified with him, he says with a glance at John: “Woman, behold, thy son.” And to John: “Behold, thy mother” (John 19:26–27). Expression, certainly, of a dying son’s solicitude for his mother’s future, yet her heart must have twinged. Once again she is directed away from him. Christ must face the fullness of his ultimate hour, huge, terrible, all-demanding, alone; must fulfill it from the reaches of extreme isolation, utterly alone with the load of sin that he has shouldered, before the justice of God.

Everything that affected Jesus affected his mother, yet no intimate understanding existed between them. His life was hers, yet constantly escaped her. Scripture puts it clearly: he is “the Holy One” promised by the angel, a title full of the mystery and remoteness of God. Mary gave that holy burden everything: heart, honor, flesh and blood, all the wonderful strength of her love. In the begi...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Introduction

- Preface

- PART ONE - The Beginnings

- PART TWO - Message and Promise

- PART THREE - The Decision

- PART FOUR - On the Road to Jerusalem

- PART FIVE - The Last Days

- PART SIX - Resurrection and Transfiguration

- PART SEVEN - Time and Eternity

- CONCLUSION

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Lord by Romano Guardini in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Systematic Theology & Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.