This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

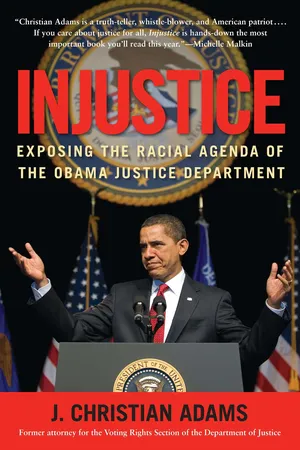

The Department of Justice is America's premier federal law enforcement agency. And according to J. Christian Adams, it's also a base used by leftwing radicals to impose a fringe agenda on the American people. A five-year veteran of the DOJ and a key attorney in pursuing the New Black Panther voter intimidation case, Adams recounts the shocking story of how a once-storied federal agency, the DOJ's Civil Rights division has degenerated into a politicized fiefdom for far-left militants, where the enforcement of the law depends on the race of the victim.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Injustice by J. Christian Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Conservatism & Liberalism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Payback Time in Mississippi

A Declaration of War

Race has affected the American experience since the nation’s earliest days. From the arrival of the first African slaves in the Virginia colony in the early 1600s, to the constitutional compromises of 1787, through the unsettled decades before Lincoln’s election, through the bloody Civil War, to three constitutional amendments promoting racial equality and their dilution over the ensuing decades—race has been a central force in our history. Through much of the twentieth century, enforcement of racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws in parts of America meant race did not play an openly contentious role— the supporters of Jim Crow ruled the field. But resentment at the political and economic oppression of one group of Americans by another boiled below the surface.

In the 1960s, the modern civil rights movement pricked the conscience of America. In the face of bitter and sometimes violent resistance, its brave adherents paved the way for Congress’s passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which together knocked down the walls of legal discrimination. After 189 years, Thomas Jefferson’s prose of 1776—that all men are created equal—was transformed from an aspiration to a legal truth.

By that time the echoes of the whip and chain had grown faint, but America could not simply seal off its past and forget it. A quick return to normalcy was impossible in a nation that had never known normalcy about racial issues.

I am reminded of my experience some years ago conducting research in Jefferson County, along the Mississippi River in the southwest corner of Mississippi, where I spent many weeks at the Jefferson County Courthouse poring over circuit court files. Lacking a single hotel, Jefferson presented a bleak economic landscape that barely resembled the rest of America. In place of the familiar national restaurant chains, a cart in the parking lot of the no-name grocer served a variety of lunchtime options, including parts of pigs I never knew people ate. Driving around the county seat of Fayette, I saw shanty-style homes that seemed to date to the turn of the last century, complete with roof holes patched with cut vegetation. It was obvious that the long history of slavery and segregation echoes across time to disadvantage present generations, whose ancestors were prevented from accumulating wealth and passing down lessons of economic success to their children.

The civil rights movement struggled valiantly to rectify the injustices of Jim Crow that had created dire circumstances for so many black Americans. Dedicated to racial equality, race-blind justice, personal responsibility, and inter-racial goodwill, civil rights pioneers like Ida B. Wells, William Monroe Trotter, Martin Luther King, and Rosa Parks were truly giants who sacrificed to make America live up to its founding ideal that all men are created equal. The moral foundation of their cause rendered it unstoppable.

But somewhere along the way, the civil rights movement transformed into something wholly different. It abandoned its commitment to legal equality and inter-racial harmony, adopting instead the ignoble goals of racial entitlements, race-based preferences, and unequal enforcement of federal law. The quintessential civil rights group, the NAACP, is a thoroughly different creature today than the eminent organization that led the nation in fighting lynching and supporting legal equality—it is now almost indistinguishable from the galaxy of organizations that comprise the racial grievance industry.

The organizers of the historic Selma to Montgomery voting rights marches weren’t motivated by anger toward whites or disdain for America’s history. They had a singular, noble mission—eradicating laws that systematically denied blacks the right to vote. Equality was their aim, not vengeance. They drew upon the long American tradition of justice to strengthen their case. As those brave marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965, to start the long walk to Montgomery, Alabama, they were confronted by rows of police officers sent by Alabama’s power brokers. Meeting at the base of the bridge, the two sides represented contrasting worldviews: one was armed with clubs and tear gas, the other had nothing except its moral authority. White and black marchers were attacked together that day, and both white and black civil rights activists were killed in Selma in the weeks surrounding the marches.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge has become a civil rights monument. Every March, activists commemorate the anniversary of the attack by recreating the march across the bridge. Notables come from all over the country to participate—Jesse Jackson, Barack Obama, Harry Reid, Al Sharpton, and Steny Hoyer have all made the pilgrimage.

The nation’s premiere voting rights museum—the National Voting Rights Museum—now sits at the foot of the bridge. The museum is an inadvertent monument to the civil rights movement’s degeneration. Its outlook is neatly captured in ten words that begin its timeline display of the civil rights movement. There, we find a replica of John Trumball’s iconic depiction of the signing of the Declaration of Independence with the caption, “1776. The Declaration of Independence signed by wealthy white men.”

The original civil rights giants would never have tolerated this historically false assertion. They were patriots, driven by love for their fellow countrymen and a burning desire to make America a better place for all its citizens. They repeatedly and vehemently rejected hatred. But the nasty caption captures the bitter spirit of much of the civil rights movement today and of numerous race-based activist groups around the country.

“Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred,” pleaded Dr. King from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963.1 This was a constant refrain in his speeches. Several years earlier, he had linked the same theme to Christian faith. Speaking of the command of Jesus to love your enemies, he preached:

Far from being the pious injunction of a utopian dreamer, this command is an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilization. Yes, it is love that will save our world and our civilization, love even for enemies. . . . If I hit you and you hit me and I hit you back and you hit me back and go on, you see, that goes on ad infinitum. It just never ends. Somewhere somebody must have a little sense, and that’s the strong person. The strong person is the person who can cut off the chain of hate, the chain of evil.2

That sentiment is irreconcilable with the bitter sense of racial grievance that is peddled today by the sullied descendents of the civil rights movement. Under the Obama administration, adherents of this radical movement have seized control of the Department of Justice and especially its Civil Rights Division. From that powerful position, they have enforced an explicitly race-based concept of justice, as described throughout this book.

But before we discuss those transgressions, readers must understand that everything the DOJ is doing today is part of a larger war between two camps: those who support a racialist future for America in which the law treats people differently according to their race, and those who support a race-blind future.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, the racialist camp met hardly any resistance as it displaced the traditional civil rights movement and spread its tentacles throughout American society. Its adherents bamboozled many Americans by appropriating Dr. King’s language of “equality,” “civil rights,” and “justice” even as they subverted the meaning of those terms, transforming them into code words for a callous system of racial spoils they are striving to impose on the entire nation. Hundreds of activist groups sprung up around the country dedicated to furthering this agenda and enshrining it in local, state, and federal law.

During this period, there was no “war” to speak of between the racialist and race-blind camps—the racialists simply moved from one victory to another, constantly strengthening their position in government and using spurious accusations of racism to snuff out any incipient signs of pushback. But that suddenly changed in 2003, when the first shot was fired back by the other side. Having become accustomed to advancing their agenda at will through any means necessary, the racialists finally went too far, provoking the Department of Justice, for the first time, to act to protect a disenfranchised white minority.

The entire conflict today between the Obama DOJ and proponents of race-neutral law enforcement is part of the war that began with that first act of resistance in 2003. And it all started not in the hallowed halls of Washington, but in a little-known, rural area of eastern Mississippi.

Named after the Choctaw for “stinking waters,” Noxubee County is located along Mississippi’s border with Alabama. Historically, the county has been sparsely populated, though its population jumped 42 percent in the 1870s thanks to an influx of black migrants attracted by the rich soil and thriving cotton industry. By 1880, the Census showed Noxubee to be 83 percent black and 17 percent white.3

Due to its unusual racial demographics, Noxubee became a focal point of the Ku Klux Klan, whose terror tactics included whipping freedmen for attempting to rent farmland, emasculating black men, whipping black women “servants” deemed too friendly with their male employers, and patrolling black areas of the country at night.4 Meanwhile, the small white minority was terrified by the potential of organized violence similar to slave uprisings throughout history, whose details they knew intimately.

Until the 1960s, white officials retained power by committing myriad abuses designed to prevent blacks from registering to vote. One of the more common schemes was for registration offices to change their hours of operation during black voting registration drives or even to close down completely when blacks came to register. If persistent black citizens chanced upon an open office, they would face a gauntlet of impossible requirements. Civics questionnaires would appear asking absurd questions such as, “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?” Character references, literacy exams, and constitutional exams most law students would fail were other tools used for the same purpose.

Today, Noxubee is about 70 percent black and 30 percent white. Corn and cattle farms dominate the pastoral landscape, punctuated by catfish ponds with huge paddlewheel aerators. Dogs sometimes trot along the road with a giant catfish in their mouths snatched from a pond, providing a welcome contrast to the multitude of dead dogs that litter the roads. Polling places are scattered in tin shacks and in old fire stations across far corners of the county, often close to rattlesnake-infested woods. Graded sandy dirt forms many, if not most, of the county’s roads, which stretch for miles in straight lines across unspoiled countryside.

Just outside the county seat of Macon, up a winding road on a hillside, is the Oddfellows Cemetery, where almost two centuries of Noxubee history is memorialized through time-worn angel monuments, broken marble crosses, and grand statutory displays. Parts of the cemetery have fallen into disrepair, testaments to a long-vanished, wealthier time. At the top of the hill is a Civil War-era plot in which rows of unknown Union soldiers lie beside rows of their unknown Confederate counterparts. These 300 dead, all that Macon could handle, were brought from Shiloh packed in lime on a train that unloaded Macon’s unsolicited share of bodies on their journey south. There is a sense of sadness here—only in death could the blue and the grey lie together in peace.

Noxubee has struggled economically since the mid-1900s, with its population dropping to around 12,000 today, a third of its 1900 level. Its 20 percent unemployment rate routinely leads Mississippi. A brick plant recently shut down, leaving a sawmill as one of the few industrial ventures providing well-paying jobs. Still, the county has its share of hard-working, industrious people, including a community of Mennonites who run successful farms and an even more successful restaurant called, simply, “The Bakery.”

In 2003, this sleepy county became ground zero in a national political war thanks to the activities of one man: Ike Brown.

Hailing from Madison County, Mississippi, Ike Brown graduated from Jackson State University in 1977. He dropped out of law school after one year and moved to Noxubee County to work in political campaigns. He was an on and off member of the statewide executive committee of the Mississippi Democratic Party, worked as a jury consultant, and eventually became chairman of the county Democratic Party. These were curious offices for someone with Brown’s history of legal problems; in 1984, he pleaded guilty to forgery charges relating to misconduct in the insurance industry, and he was convicted in federal court in 1995 of nine charges of aiding and abetting the filing of false income tax returns.

Bill Ready, a civil rights activist from Meridian, Mississippi, knew Brown and described his background to me: “Ike learned what he did from his daddy in Canton. Ike’s daddy was a runner for the white power structure, and everything Ike did in Noxubee he learned from the whites in Madison County.” Ready was literally a foot soldier in the civil rights movement. While synagogues were being dynamited and churches burned in Meridian, Ready, an attorney, represented blacks who fought back. Meridian blacks formed an armed self defense group that guarded Ready’s home and once exchanged gunfire with attacking whites.5 “We were at war,” Ready says.

The tall and lanky Brown is always a swirl of energy working on some project or scheme, sometimes many at once. Quick in conversation and boasting an encyclopedic knowledge of history and of the Dallas Cowboys, he has undeniable charisma, even if it is unpolished and rash at times. With his intelligence and charm, he became a singular force in Noxubee politics. Yet his stor...

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Acknowledgments

- Notes