eBook - ePub

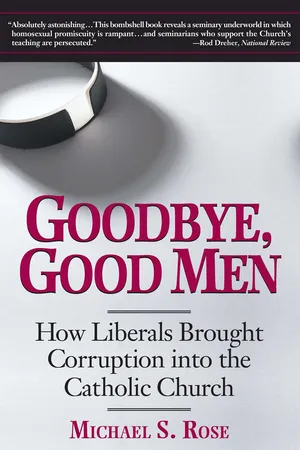

Goodbye, Good Men

How Liberals Brought Corruption into the Catholic Church

This is a test

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Goodbye, Good Men uncovers how radical liberalism has infiltrated the Catholic Church, overthrowing traditional beliefs, standards, and disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Goodbye, Good Men by Michael S. Rose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theologie & Religion & Christliche Konfessionen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theologie & ReligionSubtopic

Christliche KonfessionenCHAPTER 1

A Man-Made Crisis

Why Archbishop Curtiss Said the Priest Shortage Is “Artificial and Contrived”

It seems to me that the vocations “crisis” is precipitated by people who want to change the Church’s agenda, by people who do not support orthodox candidates loyal to the magisterial teachings of the Pope and bishops, and by people who actually discourage viable candidates from seeking priesthood and vowed religious life as the Church defines these ministries.

—Elden F. Curtiss, Archbishop of Omaha

As early as 1966, just a year after the close of the Second Vatican Council, Jesuit Father Robert E. McNally predicted an impending priest shortage. He believed that an imminent vocations crisis would devastate the Catholic priesthood. In fact, he stated that this shortage would become so acute that “in the course of the next century the Catholic priesthood might almost disappear.”1 This was a startling prediction, coming as it did at the tail end of America’s “golden age of the priesthood,”2 during the same year that seminary enrollment peaked in the United States. Nevertheless, statistics bear out at least the first part of McNally’s prophecy: There are far fewer men studying for the priesthood at the dawn of the twenty-first century than thirty years before. From 1966 to 1999, the total number of seminarians dropped from 39,638 to 4,826.3 And from 1965 to 1998 the number of graduate-level seminarians (those ordinarily within four years of ordination) dropped from 8,325 to 3,158, while priestly ordinations during that same time period dropped from 994 to 509 per year.4

Since the 1970s, when it became obvious that vocation numbers were plummeting, U.S. Catholics have been bombarded with shrill warnings that a severe shortage of priests will soon deprive them of the sacraments. The doomsayers are with us to this day, prophesying, despite evidence to the contrary, that the priest shortage will continue to worsen until, as McNally predicted, the priesthood is nearly extinct.5

How is the “vocations crisis” to be explained? Why, since the Second Vatican Council, has the Catholic Church in the United States seen fewer and fewer young men devoting themselves to the sacrificial life of the priesthood? The decline has been blamed on a multitude of factors, including materialism, practical and philosophical atheism, skepticism, subjectivism, individualism, hedonism, social injustice; parents who don’t want their sons to be priests; and the commonly perceived “unrealistic expectation” of lifelong celibacy. The failure to properly instruct Catholic youth in the faith is another important factor.

There is one instrumental component to the problem, however, which has received little attention until recently. In a 1995 article, Archbishop Elden F. Curtiss implicated vocations directors and others directly responsible for promoting vocations as having a “death wish” for the male, celibate priesthood. The article, first published in the archbishop’s diocesan newspaper, the Catholic Voice, was reprinted in Our Sunday Visitor for national distribution. Curtiss, the archbishop of Omaha, Nebraska, made a startling observation based, he said, on his experience as a former diocesan vocations director and seminary rector:

It seems to me that the vocation “crisis” is precipitated by people who want to change the Church’s agenda, by people who do not support orthodox candidates loyal to the magisterial teaching of the Pope and bishops, and by people who actually discourage viable candidates from seeking priesthood and vowed religious life as the Church defines these ministries. I am personally aware of certain vocations directors, vocations teams and evaluation boards who turn away candidates who do not support the possibility of ordaining women or who defend the Church’s teaching about artificial birth control, or who exhibit a strong piety toward certain devotions, such as the rosary.6

In other words, the very Church officials with immediate responsibility for promoting and fostering vocations are turning away qualified candidates for the priesthood. Moreover, this problem is not confined to a few such persons, but pervades nearly the entire system for recruiting and training new priests. In short, the priest shortage is caused ultimately not by a lack of vocations, but by attitudes and policies that deliberately and effectively thwart true priestly vocations.

Curtiss quickly made headlines across the country, declaring the resultant priest shortage to be “artificial and contrived.” The same people, he wrote, who have discouraged priestly vocations then turn around and promote ordination of married men and women to replace the traditional vocations they themselves have aborted. They exploit the dearth of vocations that they have helped create, to advance their efforts on behalf of a “reenvisioned priesthood” which consciously rejects the Church’s definition of the office for the Latin rite as a ministry to be exercised exclusively by celibate males.

Turning away candidates who explicitly and proudly accept the Church’s teaching, especially regarding the ordained priesthood, has been likened to “a Marine recruiter turning away prospects because they profess a love of America.”7 The conclusion then is that there is no shortage of vocations; in actuality, there are plenty of young men who exhibit what Curtiss calls “orthodoxy”—loyalty to the teachings of the Church—who are not admitted to holy orders, specifically because of their orthodox beliefs. The result is a “crisis” of ideological discrimination.

Curtiss also points out that in dioceses which support orthodox candidates there is no vocations crisis but an increase in priestly vocations. In a follow-up article published in Social Justice Review, Curtiss explained that when dioceses and religious orders are unambiguous about the priesthood as the Church defines this calling, when there is strong support for vocations, and a minimum of dissent about the male, celibate priesthood, then there are documented increases in the number of candidates who respond to the call. Speaking of his own Omaha archdiocese, he wrote that he is encouraged by the “dynamic thrust for vocations to the priesthood” and “clear indications of increases in the coming years.”8 He explained the reasons for Omaha’s success:

Our vocation strategy is drawn from successful ones in other dioceses: a strong, orthodox base that promotes loyalty to the Pope and bishop; a vocations director and team who clearly support a male, celibate priesthood and religious communities loyal to magisterial teaching; a presbyterate [i.e., the priests in a given diocese] that takes personal ownership of vocation ministry in the archdiocese; two large Serra clubs in Omaha that constantly program outreach efforts to touch potential candidates; more and more parents who encourage their children to consider a vocation to priesthood and religious life; eucharistic devotion in parishes with an emphasis on prayer for vocations; and vocation committees in most of our parishes that focus on personally inviting and nourishing vocations.9

The archbishop also cited the successful vocations numbers of Lincoln and Arlington,10 two dioceses led, at the time, by bishops who also supported orthodox vocations. Father James Gould, then vocations director for the Arlington diocese11 in northern Virginia, echoed Curtiss when he explained their formula for success: “unswerving allegiance to the Pope and magisterial teaching; perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament in parishes, with an emphasis on praying for vocations; and the strong effort by a significant number of diocesan priests who extend themselves to help young men remain open to the Lord’s will in their lives.”12

Curtiss might equally as well have pointed to any number of other successful, orthodox dioceses across the country. His own Archdiocese of Omaha, considered one of the most conservative in the Midwest, ordained an average of seven men (fifty-six total) per year from 1991 to 1998 for a population of just 215,000 Catholics. Compare that to the much more liberal diocese of Madison, Wisconsin (with a slightly larger Catholic population), which ordained a total of four men during the same eight-year period.

In the orthodox Rockford, Illinois, diocese, Bishop Thomas Doran ordained 8 priests in 1999, the highest number of ordinations there in forty-one years. Arlington ordained 55 men to the priesthood in the years 1991–98 under Bishop John Keating. In 1985 Keating had 90 diocesan priests. A decade later he had 133, nearly a 50 percent increase. And, under orthodox leadership from Bishop John J. Myers, the Diocese of Peoria,13 with a Catholic population of just 232,000, ordained 72 priests in the years 1991–98, an average of 9 each year. In comparison, the Milwaukee archdiocese under the leadership of Archbishop Rembert Weakland, with a Catholic population three times that of Peoria, ordained just 2 priests in 2001, while Detroit, with a Catholic population of 1.5 million (almost seven times that of Peoria), ordained an average of just 7 men each year from 1991 to 1998.

Other archdioceses such as Denver and Atlanta have turned their vocations programs around by actively supporting orthodox vocations and promoting fidelity to Church teaching, while emphasizing the traditional role of the priest as defined by the Catholic Church. Atlanta now has sixty-one seminarians, up from just nine in 1985. Denver boasted sixty-eight seminarians in 1999, up from twenty-six in 1991. In addition to Denver’s archdiocesan seminarians, twenty more were studying for the Neocatechumenal Way and nine for other orders. All will serve the Archdiocese of Denver when ordained.

Orthodoxy begets vocations. This is proved by the successes of the dioceses just mentioned. The converse is also true: Dissent kills vocations. It is merely common sense that says people generally do not want to give themselves to an organization whose leaders constantly bemoan its basic structures. Young men are normally not going to commit themselves to dioceses or religious orders that dissent from Church doctrine. “They do not want to be battered by agendas that are not the Church’s and radical movements that disparage their desire to be priests,” Archbishop Curtiss wrote.14

Those dioceses that have promoted dissent from the magisterial teachings of the Church have seen the sharpest decline in vocations and are now experiencing the predicted dire priest shortage. The Archdiocese of Milwaukee under the leadership of Archbishop Rembert Weakland is reputedly the most liberal and least orthodox archdiocese in the United States. Milwaukee in the 1990s consistently had a small number of seminarians, a third of the number of some dioceses a quarter its size. Weakland, of course, has long sounded the alarm about the dire priest shortage. In 1991 he issued a pastoral letter to Milwaukee Catholics telling his flock that he would ordain married men to the priesthood, subject to Rome’s approval. The Vatican was disturbed by Weakland’s public statement and reprimanded the archbishop for his “out-of-place” comments. A few years later he again expressed his doubts about the male, celibate priesthood: During the summer of 1995 he was a cosigner of a statement addressing the role of the American bishops conference in its relationship with Rome. Weakland, the only archbishop to sign the statement, expressed his disapproval of Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, Pope John Paul II’s 1994 pastoral letter which reiterated that the Catholic Church does not have the ability to ordain women to the priesthood. Weakland and his cosigners stated: “The recent apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis was issued [by the pope] without any prior discussion and consultation with our conference. In an environment of serious question about a teaching that many Catholic people believe needs further study, the bishops are faced with many pastoral problems in their response to the letter.”

Only t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A Man-Made Crisis

- Chapter 2: Stifling the Call

- Chapter 3: The Gatekeeper Phenomenon

- Chapter 4: The Gay Subculture

- Chapter 5: The Heterodoxy Downer

- Chapter 6: Pooh-Poohing Piety

- Chapter 7: Go See the Shrink!

- Chapter 8: The Vocational Inquisition

- Chapter 9: Confronting the Obstacles

- Chapter 10: Heads in the Sand

- Chapter 11: A Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Chapter 12: The Right Stuff

- Chapter 13: Where the Men Are

- Notes

- Index