![]()

Naxalite! “Spring Thunder,” Phase I

… [W]hen my child

Returns from school,

And not finding the name of the village

In his geography map,

Asks me

Why it is not there,

I am frightened

And remain silent.

But I know

This simple word

Of four syllables

Is not just the name of a village,

But the name of the whole country.

—AN EXCERPT FROM “THE NAME OF A VILLAGE,” A HINDI POEM BY KUMAR VIKAL1

Tomar bari, aamar bari, Naxalbari, Naxalbari.

Tomar naam, aamar naam, Vietnam, Vietnam.

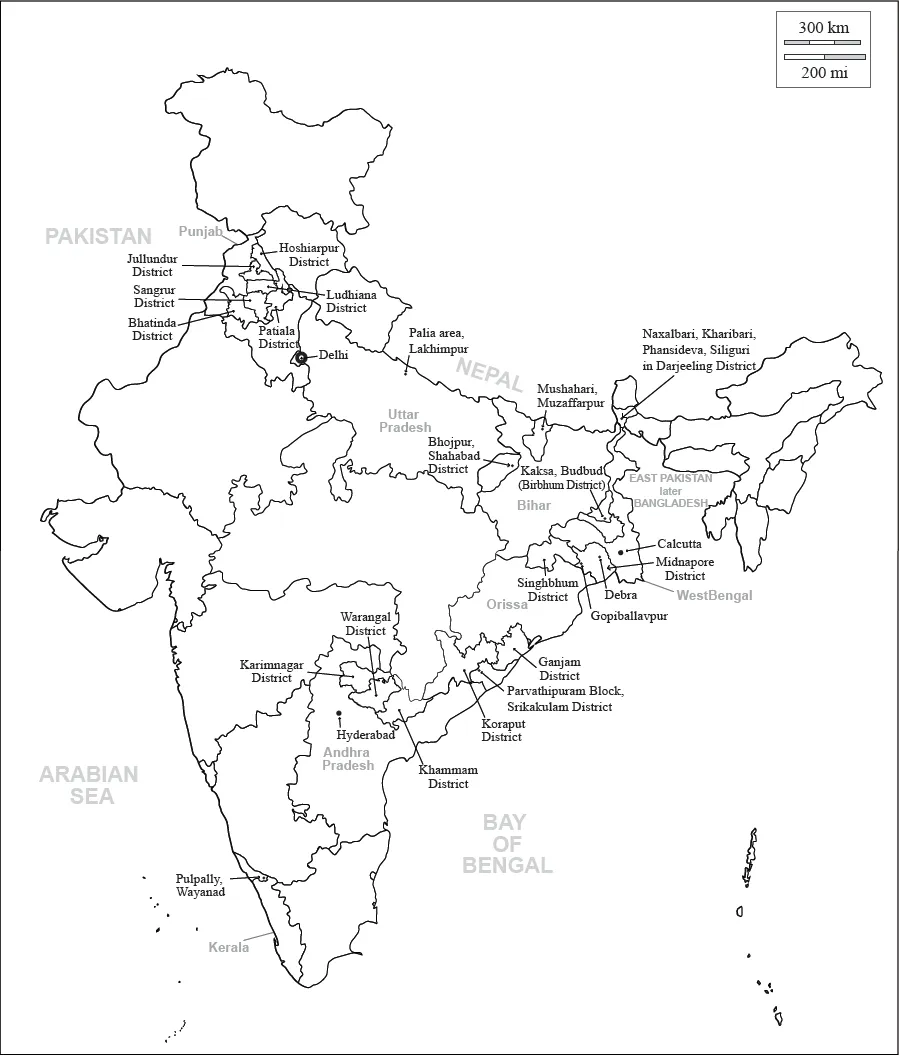

The name of the “village” was Naxalbari, situated at the foot of the Himalayas in the Darjeeling area of north Bengal, bordering Nepal to the west, Sikkim and Bhutan to the north, East Pakistan (now, Bangladesh) to the south. Naxalbari, Kharibari, Phansidewa and parts of the Siliguri police-station jurisdiction are where it all began in March 1967, and Naxalbari came to stand for this whole area. (Map 1 will be of help throughout this chapter; see pages 24 and 25.) Indeed, there was a time when conservative parents didn’t want to send their sons/daughters to Kolkata’s elite Presidency College for fear that—like the group of rebel-students who came to be known as the “Presidency Consolidation”—they might be “indoctrinated” by the “Naxalites,” Maoist revolutionaries who were given that naam (name) from the village where the movement came into being. Indeed, the term Naxalite came to symbolize “any assault upon the assumptions and institutions that support the established order in India,” and soon found “a place in the vocabulary of world revolution.”2

Map 1: Political Geography: “Spring Thunder,” Phase I (1967–75)

Note: Bolder lines indicate state/national boundaries. Thinner lines indicate district boundaries. Map is only indicative and not to scale.

Source: Map adapted from www.d-maps.com using information in Census of India.

The ’68 generation had arrived, so to say, with the Cultural Revolution in China; the “Prague Spring” (that provoked the Soviet invasion) in Czechoslovakia; the Naxalbari uprising in India; a regenerated communist party and its New People’s Army in the Philippines; soixante-huitards that were against the French establishment and the PCF (the French Communist Party); the German SDS (socialist German student league) that took on the West German establishment and the SPD (the German social-democratic party); the Civil Rights movement, fountainhead of the Black Panther Party, and the anti-(Vietnam) War movement in the United States; unprecedented student unrest, guerrilla war in the state of Guerrero, a militant labor movement, and land occupations by impoverished peasants, in Mexico, all pitted against the ruling establishment, the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), entrenched in power for decades. Revolutionary humanism was in the air; political expediency evoked derision; Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital exposed the Affluent Society for the delusion that it was; and youth, in political ferment, began to perceive the established (establishment?) left as having stripped Marxism of its revolutionary essence. Naxalbari was part and parcel of a (then) contemporary, worldwide impulse among radicals, young and not-so-young, embracing the spirit of revolutionary humanism.

But, today, all that remains of Naxalbari, in insurgent geography, is a memorial column erected by the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), the CPI(ML), in honor of the eleven who were killed in the police firing on May 25, 1967—seven women, Dhaneswari Devi, Simaswari Mullick, Nayaneswari Mullick, Surubala Burman, Sonamati Singh, Fulmati Devi, and Samsari Saibani; two men, Gaudrau Saibani and Kharsingh Mullick; and “two children,” actually infants, whose names have not been inscribed. And, of course, there are the busts of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and Charu Mazumdar, the latter, the Naxalite movement’s “ideologue” and leader in its first phase. But even as the Indian Establishment made sure that the Naxal way of life was obliterated from Naxalbari, the name acquired a symbolic meaning. It came to stand for the road to revolution in India.

The ramifications of what happened at Naxalbari, what the poor peasants’ armed struggle over there triggered, have not yet been fully deciphered. The Naxalbari armed struggle began in March 1967; by the end of July of that year, it was crushed. But, soon thereafter, in the autumn, Charu Mazumdar, who subsequently became the CPI(ML)’s General Secretary, said: “… hundreds of Naxalbaris are smoldering in India…. Naxalbari has not died and will never die.”3 Certainly, he was not daydreaming, for the power of memory and the dreams unleashed a powerful dynamic of resistance that, ever since, has alarmed the Indian ruling classes and the political establishment. Indeed, an editorial in the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Daily on July 5, 1967, hailing the creation of the “red area of rural revolutionary armed struggle” in Naxalbari as “Spring Thunder over India,” called it a “development of tremendous significance for the Indian people’s revolutionary struggle.”4

In 2017, the fiftieth year of the Naxalite movement in India, Charu Mazumdar’s statement seems almost prescient. In 1968, an ongoing struggle in Srikakulam led by two schoolteachers, Vempatapu Satyanarayana, popularly known as “Gappa Guru”—who had married and settled among the tribes—and Adibhatla Kailasam, and organized under the Ryotanga Sangrama Samiti (peasant struggle committee) with guerrilla squads in self-defense, had mobilized “almost the entire tribal population in the Srikakulam Agency Area.”5 And Warangal, Khammam, Mushahari, Bhojpur, Debra–Gopiballavpur, Kanksa–Budbud, Ganjam–Koraput, Lakhimpur, and other “prairie fires” were not far behind. The origins of the CPI (Maoist), reckoned by the political establishment in July 2006, in the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s words at a conference in New Delhi, as India’s “single biggest internal security challenge,” must be traced to its roots. After all, the Maoist armed struggle in India, alongside the one in the Philippines, is one of the world’s longest surviving peasant insurgencies.

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

In March 1967, in the “semi-feudal” setting of Naxalbari, tribal peasants organized into peasant committees under the leadership of a revolutionary group within the CPI(Marxist)—CPM hereinafter—one of the main two of India’s parliamentary communist parties,6 and with rudimentary militias armed with traditional weapons, undertook a political program of anti-landlordism involving the burning of land records, cancellation of debts, the passing of death sentences on oppressive landlords, and the looting of landlords’ guns. By May of the same year, the rebels established certain strongholds, Hatighisha (in Naxalbari), Buraganj (in Kharibari), and Chowpukhuria (in Phansidewa), where they were in control. But by the end of July, the movement collapsed under the pressure of a major armed-police action.

Be that as it may, in the Maoist view, Charu Mazumdar had not merely rebelled against the “revisionism” (stripping Marxism of its revolutionary essence) of the CPM in his writings—“Eight Documents” penned between January 1965 and April 19677—but had also given a bold call for armed struggle in the rural countryside, and his followers in Naxalbari had heeded this appeal. The West Bengal state assembly elections were held in February 1967, and in keeping with Charu Mazumdar’s suggestion that the revolutionaries should take advantage of the polls to propagate their politics, they took the benefit of the period of electoral campaigning to raise the political consciousness of the poor peasants, mainly Santhals, Oraons, and Rajbanshis, and the tea-garden workers, also tribal persons who had migrated largely from areas now part of the province of Jharkhand.

A Siliguri sub-division peasant convention and rally in mid-March 1967 swelled the ranks of the Krishak Samiti (peasant organization), which now began to prevent police from entering those villages that were considered strongholds. Any such attempt by the police led “thousands of armed peasants” accompanied by “hundreds of workers from the tea-plantations,” to foil the endeavor. “On many occasions, the police were forced to retreat. Women also played a glorious role in the revolt.… In hundreds or more, the peasants raided the houses of several landlords, seized all their possessions and snatched their guns. They held open trials of some landlords and punished a few of them. It was only in a case like that of Nagen Roychoudhuri, a notorious landlord who fired on the peasants injuring some of them, that death sentence was awarded at an open trial and was carried out. The line adopted at Naxalbari was not to annihilate landlords physically but to wage a struggle to abolish the feudal order.”

“The peasants formed small groups of armed units and peasant committees which also functioned as armed defense groups. Between the end of March and the end of April (1967) almost all the villages were organized.”8 The peasants resolved that after establishing the rule of the peasant committees in the villages, they would take possession of all land that was not owned and tilled by the peasantry and redistribute it. They did not seem to have reckoned what they would do when the armed forces of the state came to defend landlordism. On May 23, when a large police party tried to enter a village to make some arrests and the peasants resisted, a police officer was hit by arrows and he succumbed to his injuries in hospital. The police retreated but came back on May 25 in larger numbers and fired upon a group of mostly women and children when the men-folk were away, killing the eleven whom the martyrs’ memorial column honors.

The Naxalbari peasants were actually doing what the leadership of the West Bengal Krishak Sabha, controlled by the CPM, had been recommending when the party was not in office. But, now, they were advised by the same leaders, in office as part of a United Front government, to abandon their armed struggle and depend on the state machinery to settle the land question, the same state bureaucracy that had been hand-in-league with the landlords. They were even warned (threatened?) that if they didn’t give up political violence by such and such date, the police would deal harshly with them.

And, this the United Front government carried out—“Operation Crossbow” was unleashed from July 12 onward. “The entire area … was encircled by armed police and thousands of paramilitary forces. Police camps were set up in the villages. Constant patrolling of the area by armed men was carried out. The order to shoot Kanu Sanyal at sight was issued. Seventeen persons, including women and children, were killed. More than a thousand warrants of arrest were issued and hundreds of peasants were arrested.”9 According to a then superintendent of police, Darjeeling, “‘a powerful Army detachment was standing by on the fringe of the disturbed area.’”10 Indeed, even after the operation was successfully accomplished, thousands of armed police remained in the Naxalbari area, even until 1969. Perhaps what unnerved the Establishment was the “very remarkable” coming together of the tea-plantation workers and the peasants, for on many an occasion, the peasants and the plantation workers, both essentially armed with their traditional weapons, “together forced the police to beat a retreat.”11

But, despite such high points, the Naxalbari uprising, unable to take on the might of the repressive apparatus of the state, met quick defeat. The local leaders of the movement—Kanu Sanyal, Khokan Mazumdar, Jangal Santhal, Kadam Mullick, and Babulal Biswakarma—did not initiate the building of armed guerrilla squads nor did they establish a “powerful mass base,” as Sanyal later wrote in self-criticism. So they could not maintain their strongholds, even temporarily. The consequences of the uprising were, however, far-reaching. The rural poor in other parts of the country were inspired to undertake militant struggles. As Sumanta Banerjee, who has penned one of the most moving and authentic accounts of Naxalbari and what happened in its aftermath, put it: “It was like the premeditated throw of a pebble bringing forth a series of ripples in the water…. The world of landless laborers and poor peasants … leapt to life, illuminated with a fierce light that showed the raw deal meted out to them behind all the sanctimonious gibberish of ‘land reforms’ during the last 20 years…. [Indeed, in keeping with the gravity of the situation, in November 1969] the then Union Home Minister, Y. B. Chavan warned that ‘green revolution’ may not remain green for long.… A general belief in armed revolution as the only way to get rid of the country’s ills was in the air, and the possibility of its drawing near was suggested by the Naxalbari uprising.”12 And, as the other authoritative, independent account of the movement, that of Manoranjan Mohanty, put it: “… the Naxalbari revolt became a turning point in the history of Independent India by challenging the political system as a whole and the prevailing orientation of the Indian Communist movement in particular.”13

Be that as it may, with defeat right at the time of the launch of the strategy of area-wise seizure of power staring the Maoist leadership in the face, the intent, the area-wise seizure, was glossed over by sympathizers, and the movement was depicted as one intending mere land redistribution. Nevertheless, “revisionism” came under severe attack, especially in West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh, where the Naxalite movement first established some strongholds, for the rebellion exposed the parliamentary left’s, in particular the CPM’s, politics of running with the hare and hunting with the hounds. The armed police that suppressed the peasant uprising at Naxalbari in 1967 were under orders from a coalition government of which the CPM was a prominent partner. The positive fallout was, however, the fact that some CPM members were deeply moved by Naxalbari. They posed the question as to why the party, even as it swore by “people’s democratic revolution,” refused to make any preparations—ideological, political, organizational and military—whatsoever to bring it about.

But instead of bridging the gap between the party’s stated revolutionary intention and its actual “revisionist” practice, the CPM leadership threw the rebels out of the party. Operation Expulsion involved not only the purging of Charu Mazumdar, Kanu Sanyal, and the other local leaders of the Naxalbari uprising, but also Sushital Roy Chowdhury, a member of the West Bengal State Committee of the CPM, as well as the removal of other prominent party members such as Saroj Dutta, Parimal Dasgupta, and Pramod Se...