Appendix One

Denis Diderot, Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who Can See (1749)

Note on the Translation

This is the first English translation and edition of the Lettre sur les aveugles since the eighteenth century when it first appeared in 1770 as A Letter on Blindness. For the Use of those who have their Sight (see Figure 4).427 That work was reprinted with some modifications and various appendices in 1780 and again in 1783 with the title, An Essay on Blindness, in a Letter to a Person of Distinction.428 It also served as the basis for Margaret Jourdain’s translation (1916),429 which has recently been reproduced by David Adams in Denis Diderot, Thoughts on the Interpretation of Nature and other Philosophical Works (2000).430

Diderot was himself a translator of English into French and so is ***, who claims to have translated part of a fictitious work from English, the Life and Character of Dr Nicholas Saunderson, supposedly written by one William Inchlif Esq. *** observes that readers who are able to read the work in the original, ‘y remarqueront un agrément, une force, une vérité, une douceur qu’on ne rencontre dans aucun autre récit, et que je ne me flatte pas de vous avoir rendus, malgré tous les efforts que j’ai faits pour les conserver dans ma traduction’ [will remark in it a certain something that is charming, powerful, true and gentle, which is to be found in no other tale and which I do not flatter myself to have rendered for you, in spite of all the efforts I have made to preserve it in my translation]. ***’s claim is ironic, not least because it would seem that there is no real original to which the reader could compare his translation.431 That is not the case for the readers of my translation and so the sentiments that *** expresses ironically are ones that I wish to express here for real.

The two footnotes are Diderot’s, as is the Index. The endnotes are mine and have been kept to a minimum. Where the Letter makes reference to other works of the period, the endnotes refer, where available, to the standard English translation. Names are given in their modern spelling (e.g. ‘Puiseaux’ for ‘Puisaux’, ‘Molyneux’ for ‘Molineux’) or have been corrected (e.g. ‘Raphson’ for ‘Rapson’, ‘Saunderson’ for ‘Saounderson’). The six plates are reproduced by courtesy of the University Librarian and Director, The John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester.

Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who Can See

Possunt, nec posse videntur1

(London, 1749)2

I had my doubts, Madame, about whether the blind girl whose cataracts Monsieur de Réaumur3 has just had removed, would reveal to you what you wanted to know, but it had not occurred to me that it would be neither her fault nor yours. I have appealed to her benefactor in person and through his best friends, as well as by means of flattery, but to no avail, and the first dressing will be removed without you. Some highly distinguished people have shared with the philosophers the honour of being snubbed by him. In a word, he only wanted to perform the unveiling in front of eyes of no consequence.4 Should you be curious to know why that talented Academician makes such a secret of his experiments, which cannot, in your view, have too many enlightened witnesses, I should reply that the observations of such a famous man do not so much need spectators while they are being performed as an audience once the performance is over. So, Madame, I have returned to my initial plan, and having no choice but to miss out on an experiment which I could not see would be instructive for either you or me, but which will doubtless serve Monsieur de Réaumur rather better, I began philosophizing with my friends on the important matter that it concerns. How delighted I should be were you to accept the account of one of our conversations as a substitute for the spectacle that I so rashly promised you!

The very day that the Prussian5 was performing the cataract operation on Simoneau’s daughter,6 we went to question the man-born-blind of Puiseaux.*432He is a man not lacking in good sense and with whom many people are acquainted. He knows a bit of chemistry and followed the botany lessons in the King’s Garden quite successfully.7 His father taught philosophy to much acclaim in the University of Paris and left him an honest fortune, which would easily have been enough to satisfy his remaining senses had his love of pleasure not led him astray in his youth. People took advantage of his inclinations, and he retired to a little town in the provinces whence he comes to Paris once a year, bringing with him liqueurs of his own distillation, which are much appreciated. There you have, Madame, some details which, though not very philosophical, are for that very reason all the more suitable for persuading you that the character of whom I am speaking is not imaginary.8

We arrived at our blind man’s house around five o’clock in the evening to find him using raised characters to teach his son to read. He had only been up for an hour, since, as you know, the day begins for him as it ends for us. His custom is to work and see to his domestic affairs while everyone else is asleep. At midnight, there is nothing to disturb him and he disturbs no one. The first task he undertakes is to put back in its place everything that has been moved during the day, and his wife usually wakes up to a tidy house. The difficulty the blind have in finding things that have been mislaid makes them fond of order, and I have noticed that people who are well acquainted with them share this quality, either owing to their good example or out of a feeling of empathy that we have for them. How unhappy the blind would be without the small acts of kindness of those around them! And how unhappy we would be too! Grand gestures are like large gold and silver coins that we rarely have any occasion to spend, but small gestures are the ready currency we always have to hand.

Our blind man is a very good judge of symmetry. Between us, symmetry is perhaps a pure convention, but between a blind man and the sighted, it is certainly so. By using his hands to study how the parts of a whole must be arranged such that we call it beautiful, a blind man can manage to apply this term correctly, but when he says that’s beautiful, he is not judging it to be so; he is simply repeating the judgement of the sighted. And is that any different to what three quarters of people do when they judge a play they have listened to or a book they have read? To a blind man, beauty is nothing more than a word when it is separated from utility, and with one less sense organ, how many things are there, the utility of which escapes him? Are the blind not to be pitied for deeming beautiful only what is good? So many wonderful things are lost on them! The only compensation for their loss is the fact that their ideas of beauty, though much less broad in scope than ours, it is true, are much more precise than those of the clear-sighted philosophers who have written long treatises on the subject.

Our blind man constantly talks about mirrors. You are right in thinking he does not know what the word ‘mirror’ means, and yet he will never place a mirror face down. He expresses himself with as much sense as we do about the qualities and defects of the organ he lacks, and though he does not attach any ideas to the terms he uses, he nonetheless has an advantage over most other men in that he never uses them incorrectly. He speaks so well and so accurately on so many things that are absolutely unknown to him, that conversing with him would undermine the inductive reasoning we all perform, though we have no idea why, which assumes that what goes on inside us is the same as what goes on inside others.

I asked him what he understood by a mirror: ‘A machine,’ he replied, ‘that projects things in three dimensions at a distance from themselves if they are correctly placed in front of it. It is like my hand inasmuch as I mustn’t place it to one side of an object if I want to feel it.’ Had Descartes been born blind, he would, it seems to me, have congratulated himself on such a definition. Indeed consider, if you will, the subtlety with which he had to combine certain ideas in order to arrive at it. Our blind man knows objects only through touch. He knows on the basis of what other men have told him that it is by means of sight that we know objects just as they are known to him through touch. At least, that is the only notion he can have of sight. He also knows that we cannot see our own faces, though we can touch them. Sight, so he is bound to conclude, is a kind of touch that only applies to objects other than our faces and which are located at a distance from us. Moreover, touch only gives him the idea of three dimensions and so he will further believe that a mirror is a machine that projects us in three dimensions at a distance from ourselves. How many famous philosophers have employed less subtlety to arrive at notions that are equally false? How surprising must a mirror be for a blind man though? And he must have been even more astonished when we told him that there are other machines that enlarge objects and others still that, without duplicating the objects, make them change place, bring them closer, move them further away, make them visible and reveal their tiniest parts to naturalists’ eyes, and that there are some that multiply objects by the thousand and others that seem to alter what they look like completely. He asked us hundreds of bizarre questions about these phenomena. For example, he asked if it was only people called naturalists who could see with a microscope, and whether astronomers were the only people who could see with a telescope, whether the machine that enlarges objects was larger than the object that makes them smaller, whether the one that brings them closer was shorter than the one that moves them further away, and he was completely unable to understand how that other one of us who is, as he put it, repeated in three dimensions by the mirror, could elude the sense of touch. ‘Here you have two senses’, he said, ‘that are made to contradict each other by means of a little machine. A better machine might perhaps make them agree with each other without the objects being any more real as a result; and perhaps a third, even better and less perfidious machine would make them disappear altogether and notify us of the error.’

‘In your opinion, what are eyes?’ Monsieur de … asked him. ‘They are organs’, replied the blind man, ‘that are affected by the air in the same way as my hands are affected by my stick.’ His reply took us aback, and as we stared at each other in wonder, he continued, ‘That must be right because when I place my hand between an object and your eyes, you can see my hand but not the object. The same thing happens to me when I am looking for one thing with my stick and I come across something else instead.’

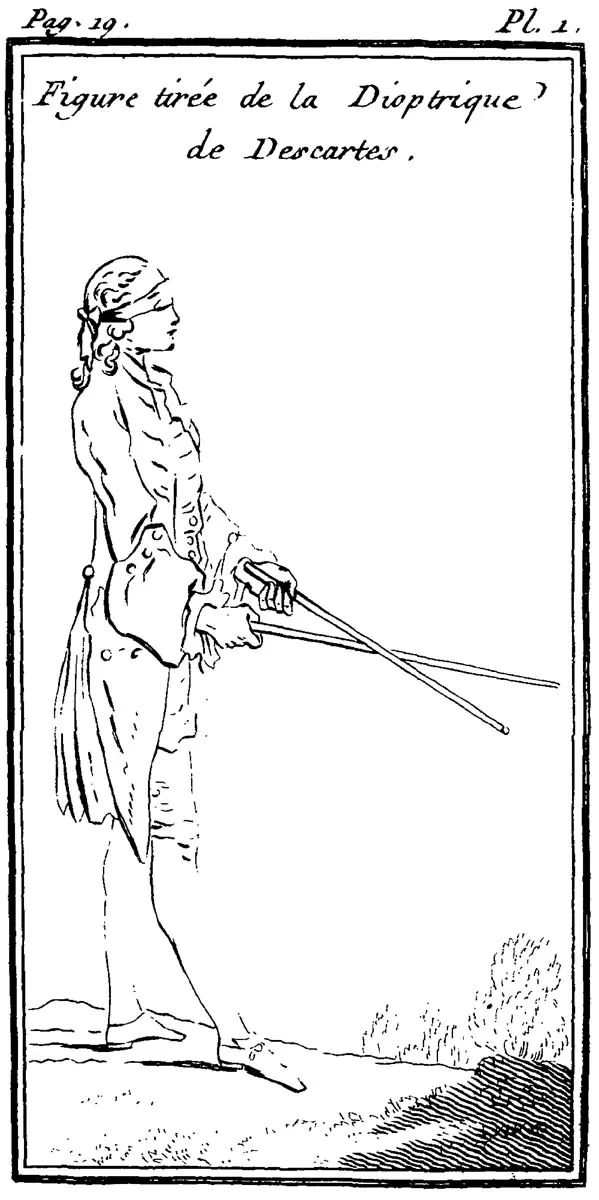

Madame, open Descartes’ Dioptrics and there you will find the phenomena of vision related to those of touch, and optical plates full of men seeing with sticks.9 Descartes and all those who have come after him have been unable to provide any clearer ideas of vision, and in this respect the great philosopher’s superiority over our blind man was no greater than that of the common man who can see.

None of us thought to ask him about painting and writing, but it is clear that there is no question to which his comparison could not give a satisfactory answer, and I am in no doubt that he would have said that trying to read or see without eyes was like looking for a pin with a great big stick. We spoke to him only of those kinds of pictures that use perspective to give objects three dimensions and which are both so similar and so different to our mirrors, and we realized they confused as much as they confirmed his understanding of a mirror and that he was tempted to believe that since a mirror paints objects, a painter representing them would perhaps paint a mirror.

We saw him thread very small needles. Might I ask you, Madame, to look up from your reading here and imagine how you would proceed if you were he? In case you can’t think how, I shall tell you what our blind man does. He places the needle long-ways between his lips with the eye of the needle facing outwards and then, sucking in with his tongue, he pulls the thread through the eye, except when it is too thick, but in that case someone who can see is in no less difficulty than someone who can’t.

He has an amazing memory for sounds, and faces afford us no greater diversity than voices do him. They present him with an infinite scale of delicate nuances, which elude us because we do not have as much interest in observing them as the blind man does. Such nuances are like our own faces inasmuch as, of all the faces we have ever seen, the one we recall the least well is our own. We only study faces to recognize people, and if we cannot remember our own, it is because we will never be in the position of mistaking ourselves for someone else nor someone else for ourselves. Moreover, the way the senses work together prevents each one from developing on its own. This will not be the only time I shall make this observation.

On this matter, our blind man told us that he might have thought himself to be pitied for lacking our advantages and have been tempted to see us as superior beings, had he not on hundreds of occasions felt how much we deferred to him in other ways. This remark prompted us to make another. This blind man, we said to ourselves, has as high a regard for himself as he does for those of us who can see, perhaps even higher. Why then if an animal has reason, which we can hardly doubt, and if it weighed up its advantages over those of man, which it knows better than man’s over it, would it not pass a similar judgement? He has arms, the fly might say, but I have wings. Though he has weapons, says the lion, do we not have claws? The elephant will see us as insects; and while all animals are happy to grant us our reason, which leaves us in great need of their instinct, they claim to be possessed of an instinct, which gives them no need for our reason. We have such a strong tendency to overstate our qualities and underplay our faults that it would almost seem as though man should be the one to do the treatise on strength, and animals the one on reason.

One of us decided to ask our blind man whether he would like to have eyes. He replied, ‘If I wasn’t so curious, I’d just as well have long arms, as it seems to me that my hands could teach me more about what’s happening on the moon than your eyes or telescopes can, and besides, eyes stop seeing well before hands stop touching. It would be just as good to improve the organ I already have, as to grant me the one I lack.’

Our blind man locates noises or voices so accurately that I have no doubt that, with practice, blind people could become highly skilled and highly dangerous. I shall tell you a story that will convince you how wrong we would be to stay still were he to throw a stone at us or fire a pistol, regardless of how little practice he might have had with a firearm. In his youth, he had a fight with one of his brothers who came out of it very badly. Angered by some unpleasant remarks that his brother directed at him, he seized the first object that came to hand, threw it at him, hit him right in the middle of his forehead and ...