eBook - ePub

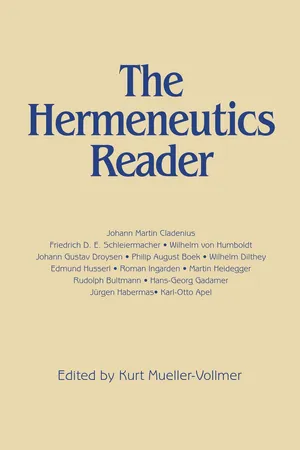

Hermeneutics Reader

Texts of the German Tradition from the Enlightenment to the Present

This is a test

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hermeneutics Reader

Texts of the German Tradition from the Enlightenment to the Present

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Essays discuss reason and understanding, interpretation, language, meaning, the human sciences, social sciences, and general hermeneutic theory. Kurt Mueller-Vollmer is Emeritus Professor of German Studies and Humanities at Stanford University

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hermeneutics Reader by Kurt Mueller-Vollmer, Kurt Mueller-Vollmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Reason and Understanding: Rational Hermeneutics

Johann Martin Chladenius

Johann Martin Chladenius (1710-1759) was born in Wittenberg the son of a theologian, Martin Chladenius. He attended the Gymnasium (classical high school) in Coburg until the age of fifteen and studied at the University of Wittenberg where he received a master’s degree in 1731. In 1732 he began teaching as a teaching master (Magister legens) in Wittenberg, at first in philosophy and later in theology as well. After habilitating himself with a doctorate in ancient church history in Leipzig, he became a professor at that university in 1742. In 1744 he quit his post in order to become headmaster of the Gymnasium at Coburg. He accepted a professorship for “theology, rhetoric, and poetry” at the University of Erlangen in 1748, where his duties required that he obtain an additional doctorate in theology. He stayed at Erlangen until his death. Chladenius was a prolific writer on a great many topics in theology, history, philosophy, and pedagogy. Important for the development of hermeneutics were his Science of History (Allgemeine Geschichtswissenschaft of 1752 and his New Definitive Philosophy (Nova philosophia definitiva) of 1750 which contains a chapter on hermeneutic definitions. Among Chladenius’s predecessors must be mentioned Konrad Dannhauer (Idea boni Interpretes—The Idea of the Good Interpreter, 1630), J.G. Meister (Dissertatio de interpretatione—Dissertation on Interpretation, 1698) and above all, Johann Heinrich Ernesti with his work on secular hermeneutics (De natura et constitutione Hermeneuticae profanae—On the Nature and Constitution of Secular Hermeneutics, 1699). Chladenius’s Introduction to the Correct Interpretation of Reasonable Discourses and Writings, published in Leipzig in 1742, was the first systematic treatise on interpretation theory written in German. Even though Chladenius’s work was well received and widely discussed among his contemporaries, it did not bring about the establishment of general hermeneutics as an independent branch of philosophy as its author had hoped. The following selections comprise chapters 4 and 8 of the Introduction. They deal with Chladenius’s concept of interpretation (selection 1) and the interpretation of historical writings (selection 2). It is in the latter that Chladenius develops his famous notion of the point-of-view or perspective (Sehe-Punkt). The remaining chapters of the book deal with topics like the classification of discourses and writings, the nature of words and their meaning, the interpretation of discourses and the interpretation of writings, and with the general characteristics of interpretations and the task of the interpreter. For literature on Chladenius, see Bibliography, Section A.

On the Concept of Interpretation

148. Unless pretense is used, speeches and written works have one intention—that the reader or listener completely understand what is written or spoken. For this reason, it is important that we know what it means to completely understand someone. Here it would be best if we agree only to review certain types of books and speeches which we fully understand so that we may then be able to arrive at a general concept.

149. A history which is told or written to someone assumes that that person will use his knowledge of the prevailing conditions in order to form a reasonable resolution. This aim can also be upheld by virtue of the nature of the account and our own common sense. If, then, we can obtain an idea of the conditions from the account which will allow us to make an appropriate decision, we have completely understood the account.

If, for example, a commander receives an unsigned letter from a good friend which tells of a fortress which is to be taken by surprise, the letter would of course possibly cause the commander to think that it is perhaps his fortress which is meant and that he must therefore be on the alert; assuming that this letter is to be read as a warning. If these thoughts are aroused in the commander and he subsequently examines the necessity of further circumspection, then he has completely understood the message. But if more details are reported to him, then he will have to make a more definitive and determined resolution in correspondence with these. This must also take place, if he is to have thoroughly understood the letter.

150. One can acquire general concepts and moral lessons from histories and the author may, in fact, intend to teach us these concepts and lessons. If we read a story written with such intentions and really learn the concepts and lessons which can and should be extrapolated, then we have completely understood the history and the book.

151. Stories are also told and written in order to amuse the reader and listener. Here there must be something in the story which causes pleasure when we imagine it in our mind. If in reading and hearing a story of this kind I focus my attention on just that which is able to bring about the pleasure and if I consequently experience the pleasure which is intended, then I have understood the book completely. This category includes the many collections of funny stories which one cannot fully understand if one does not sense the intended pleasure himself.

152. One fully understands an order if one can discern the will of the person giving the command, insofar as he wanted to make his will known. One soon sees from this that it is difficult to understand laws and commands; for it is not enough that I—depending on the type of command—discover the nature of the will of the commanding person, but it is essential to understand the extent to which he has expressed his will in words and how much of this he wants to have me know about. For in actuality, the will of the superior is not the concern of the person receiving the order beyond the extent to which it can be perceived in his words. The rest, which is not present in the words of the command, is not considered part of the command.

153. It is another thing to understand a proposition in itself and to understand it as being presented and asserted by someone; the latter only concerns us in the interpretation. From Descartes we have the statement: One should doubt all things once. If I say I understand the statement completely then this means that I am acquainted with Descartes’s opinions, which can either be correct or incorrect, founded or unfounded. We can accept this as a sign of complete understanding if the statements deduced or inferred by the author of the proposition are also made understandable by the same.

154. A meaningful oration or written work is presented or written in order to cause a stirring in our souls. These stirrings serve joy, laughter, seriousness, shame, sadness, and other emotions. An obstacle may be present which does not allow these emotions to be awakened at certain times and in certain people. But, if in listening to or reading a meaningful oration or writing one senses the intended emotion, or at least sees that such an emotion could result if there were no obstacles, then one has fully understood that oration or writing.

155. If, drawing from the examples we have cited, one fully understands this or that writing, one can make the following general concept by abstraction. One understands a speech or writing completely if one considers all of the thoughts that the words can awaken in us according to the rules of heart and mind.

156. There should be no difference between fully understanding a speech or writing and understanding the person who is speaking or writing. For they too have the same rules to consider as the reader and the listener. Thus, the speaker or writer can be thinking of the same thing as the reader or listener when he uses certain words. Consequently, it would make no difference whether I imagine what the writer thought by using certain words, or whether I reflect about what one could imagine with these words according to the rules. Because one cannot foresee everything, his or her words, speeches, and writings may mean something which was not intended. Thus in trying to understand these writings, we may think of something which the writer was not conscious of. It can also happen that a person imagines or thinks that he has expressed his opinion in such a way that one would have to understand him. But everything still is not there in his words which would enable us to completely comprehend the sense of what he is saying. Therefore, we always have two things to consider in speeches and in written works: a comprehension of the author’s meaning and the speech or writing itself.

157. A speech or written work is completely understandable if it is constructed so that one can fully understand the intentions of the author according to psychological rules. But if one cannot understand everything which the author intended from his words, or if one is caused with reason to consider more than the author wanted to say, then the writing is not understandable. In keeping with our remarks in 156, all books and speeches produced by people will have something in them which is not understandable.

158. The concept of the intelligible and the unintelligible may be applied to every part or passage in a speech or in a book.

159. We do not understand a word, sentence, speech, or writing at all if we do not retain anything. But it is impossible for us not to understand a book written according to a grammar and lexicon with which we are familiar. It is possible, however, that we do not completely understand it. For full understanding takes place only when one imagines all things which can be thought of with each word according to psychological rules (155). So the complete understanding of a speech or writing must encompass a number of concepts. If we are still lacking some of these concepts which are necessary for this full understanding, then we still have not understood the passage completely.

160. And so one can understand very little of a speech or book if we are still lacking many of the concepts necessary for its comprehension. In everyday life one does not analyze things and certainly not in the manner that is necessary for interpretation. One commonly claims not to have understood a book at all instead of saying, as one should, that we have only understood’some of the book.

161. Experience teaches us that we understand a book better the second time when we have only understood very little on the first cursory reading; for in general, the more often we read a book, the more we understand it, which is the same as saying that we think more about the words and so come closer to a full understanding (155). If one thinks more about a book in retrospect and with reason, we say that we are learning to read the book.

162. If we do not entirely comprehend a book, three situations are possible: either we do not understand some passages at all, or we understand all passages incompletely, or both; rather than saying that we do not understand some passages at all or others incompletely.

163. Learning to understand a book, then, means either that one understands a passage which one previously did not understand, or that both happen simultaneously (162), which will more often be the case.

164. If the sense of a passage is certain, it is called a clear passage; if the meaning is uncertain or unknown, it is a dark passage. A passage that is capable of stimulating all sorts of thoughts in us is considered productive. But if it does not give us any concepts, or fewer than one desires, then we shall call it unproductive.

165. The passages of a speech or written work are often less productive than their creator imagines, because he often puts more into words than he can reasonably expect his reader to perceive (156). And, on the other hand, some passages are often more productive than the author thinks because they inspire many more thoughts than he intended, some of which he would rather have left unthought.

166. If one learns to understand a book, many thoughts arise in us which we had not had before reading it (161). If this happens because we now understand passages which we formerly did not understand at all (163), then a dark passage has become clear and somewhat productive (164). But if we learn to understand certain passages better, then the unproductive passages will have become more productive. Consequently, our learning to understand a text consists of dark passages becoming clear and unproductive ones becoming productive.

167. Time has no influence on this process but on the things themselves which change in time. Therefore, because we learn to understand a book with time (160), it does not mean that the cause must lie in time, but that it was the thoughts which arose and were changed in our mind. If one wants to learn to understand a book a little at a time, then one must acquire the concepts which are necessary for a complete understanding of the book.

168. These concepts, which we slowly acquire and are the cause for our learning to understand a book (167), either originate in us independently of the book, or we have acquired them because we expected to learn to understand the book through them. Imagine that we are reading Cicero’s speech before Milo. At first, much will appear which we do not understand. Some things will become understandable to us later only if we read the speech again. We soon realize that a knowledge of Roman history and antiquity would contribute a great deal to our comprehension of the speech. Before we undertake another reading of the speech we take a look at these related works and discover how much our comprehension of this beautiful speech has increased.

169. There is nothing more common than someone, who, in his desire for us to understand a certain book, will teach us those concepts necessary for its understanding. And we say of this person that he has interpreted the book for us. An interpretation is, then, nothing other than teaching someone the concepts which are necessary to learn to understand or to fully understand a speech or a written work.

170. It may just so happen that we ourselves will arrive in time at the concepts necessary for the understanding of a text (168). But this method alone is copious and precarious. We can achieve our goal more quickly if we can learn the concepts we are lacking from someone who fully understands the book and knows which concepts we need to acquire. We could act as interpreters ourselves in the hopes that we would be lucky enough to hit upon the correct and necessary concepts, but it would still be easier, if someone who understands the book were to help us.

171. Since an interpretation only takes place if we are still lacking certain concepts necessary to the complete understanding of the book, the interpreter’s duty terminates when we completely understand the work.

172. If we should ask for an interpreter, then we should acknowledge that we have not completely understood the book. The next simple question one might ask is how we know that we still do not completely understand the meaning of a book. This conjecture may have a good many causes, so we shall only take a few of these as examples.

173. If an account which we hold to be true, as the author would have it, seems to contain things which contradict another account also purported to be true, then we still do not understand either one of the two or both of them completely. We will show in the following that a true account can appear to contradict another one. The fault of the apparent contradiction is to be found in the person who feels that the narrative does not present the nature of things the same way as he perceives it. From this one can conclude that we either read too much or too little into the words and, therefore, do not have the correct concepts which the words should call forth. We consequently still do not fully understand the history.

174. If we read a story which is acclaimed for its ingenuity and we know that many people have been inspired by it, yet we still remain unmoved by it, then this is also a sign that we have not yet understood it. This also applies to an ingenious speech. The complete understanding of such a text demands that we be moved by it, or, at least, that we recognize how the text could move certain readers or listeners (154). It follows that if we do not sense any of these things, then we have not completely understood it.

175. If we are certain from specific details that a commanding officer has made his will known to us and things nevertheless occur where we no longer know what his intent is, then we have not completely understood the commands and laws which were given to us. For if a commanding officer has made his will known to us, there must be enough cause contained in the words of the orders and laws for us to understand his will from them. If we perceive this, then we would fully understand the laws and commands (152). But because we do not know his will, regardless of its having been made known to us, then we must not have fully understood the laws and commands in this instance.

176. In this and in other cases where we do not fully understand a text we need an interpretation. The interpretation is different in each instance so that another interpretation must be used for every dark or unproductive passage (169). The interpretation may express itself in an infinite number of ways, but, just as all repeated human actions proceed according to certain laws, an interpretation is also bound by certain principles which may be observed in particular cases. It has also been agreed that a discipline is formed if one explains, proves, and correlates many principles belonging to a type of action. There can be no doubt, then, that a discipline is created when we interpret according to certain rules. For this we have the Greek name “hermeneutic” and in our language we properly call it the art of interpretation.

177. Very little knowledge of this discipline can be found in the field of philosophy. It consists of a few rules with many exceptions which are only suitable for certain types of books. These rules, which were not allowed to be regarded as a discipline, were given a place among the theories of reason. The theory of reason deals with matters pertaining to general epistemology and cannot go into the area of history, poetry, and other such literature in depth. For this is the place of interpretation and not a theory of reason. Hermeneutics is a discipline in itself, not in part, and can be assigned its place in accordance with the teachings of psychology.

178. Aside from the shortcoming mentioned above, as to the unsuitable placement of this discipline (177), other oversights were made which have distorted its reputation and made it unrecognizable. Philology and criticism, insofar as the latter consists of improving and restoring damaged passages, have almost always been associated with hermeneutics; but when the critic and philologist have done their work on a book, the work of the interpreter is just beginning. One has arrived at the notion that this admixture of philologist and critic could constitute an excellent interpreter. Indeed, we have them to thank for the fact that we receive the book in its entirety and that we can clearly discern the text. All of these are great merits but differ only too greatly from those of interpretation. Many interpretations that were advanced with this belief in mind lacked the necessary prerequisites.

179. Many things were demanded of interpretations which were impossible, either in themselves, or according to the few principles of interpretation which were available. An interpretation can only take place if the reader or listener cannot understand one or more passages (169, 170). On the other hand, it is impossible to find an interpretation if the words in themselves do not contain anything from which the meaning can be conjectured or ascertained with certainty. The interpreter has been called to give meaning to such dark and ambiguous passages, which is of course impossible. To ask him to give even a probable meaning to these passages would be too great a demand, for an interpreter is not in a position to be called to account for passages, even when their meaning is obvious and clear. It cannot be denied that a probable interpretation can be made where a certain one is not possible, but this would be too difficult to put into rules since a rational theory of probability has not yet been sufficiently developed, even though the manner by which we obtain certain truths has been thoroughly ascertained. It is no wonder then that the theory of interpretation has been attacked in its most difficult chapter and that it has not been easy to come away from this.

180. Yet another type of interpretation has come to be grouped with the main type and has also been a considerable hindrance to the progress of the discipline. We express both our perceptions of things and our desires when we speak or write. In fact, in some speeches and written works, we have no other aim than to explain to someone else what we know or want—as is the case, for example, in contracts and transact...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Language, Mind, and Artifact: An Outline of Hermeneutic Theory Since the Enlightenment

- 1. Reason and Understanding: Rationalist Hermeneutics

- 2. Foundations: General Theory and Art of Interpretation

- 3. Foundations: Language, Understanding, and the Historical World

- 4. Philological Hermeneutics

- 5. The Hermeneutics of the Human Sciences

- 6. The Phenomenological Theory of Meaning and of Meaning-Apprehension

- 7. Phenomenology and Fundamental Ontology: The Disclosure of Meaning

- 8. Hermeneutics and Theology

- 9. The Historicity of Understanding

- 10. Hermeneutics and the Social Sciences

- 11. Perspectives for a General Hermeneutic Theory

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Index of Persons

- eCopyright