This is a test

- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

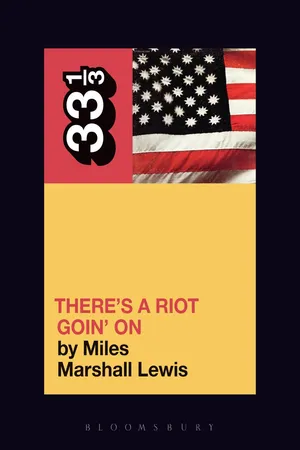

Sly and the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The story behind the making of the album that signaled the descent of Sylvester Sly Stone Stewart into a haze of drug addiction and delirium is captivating enough for the cinema. In the spacious attic of a Beverly Hills mansion belonging to John and Michelle Phillips (of the Mamas and the Papas) during the fall of 1970, Sly Stone began recording his follow-up to 1969's "Stand!" the most popular album of his band's career.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sly and the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On by Miles Marshall Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Rockmusik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Believer Whose Faith

Was Shattered

1

Picture thirty years after the Woodstock Festival’s three days of peace and music, into the premillennial days of 1999. Visualize through the eyes of a contemporary counterpart of someone like Meredith Hunter, the black teen murdered by Hells Angels at the Rolling Stones’ Altamont concert, who’d certainly have thought Sly and the Family Stone at Yasgur’s farm in ’69 was totally far out. For the sake of argument let’s say this modern-day Meredith wears dredlocks in place of his antecedent’s Afro, smokes as much weed as Meredith might’ve, and rents a brownstone apartment in the heart of bohemian Fort Greene, Brooklyn.

Such a location means he has a neighbor in Erykah Badu, who represents something of particular significance to the young brother. (We’ll call him Butch.) Erykah Badu arrived from Dallas, Texas, three years ago, like a hiphop Joan Baez for the incense-and-oils set, to this section of Brooklyn where most of the women already look like her: African headwraps, ankh jewelry pieces, thrift store fashion. For Butch the runaway success of her 1997 debut Baduizm and its Live album followup means something. In specific he thinks the singer’s tendency toward preaching her earth mama philosophy to sold-out audiences implies that spiritual knowledge is being spread, that consciousness is being raised to a tipping point, that Erykah Badu fans will spill out of nationwide venues discovering holistic healing and transcendental meditation and Kemetic philosophy and vegan diets for themselves. What would this mean, for the millions who follow Erykah Badu’s music to embrace the singer’s lifestyle on a mass level at this specific period in time, the cusp of the Aquarian age? Butch wonders.

But that’s not all. In April Butch saw The Matrix in a crowded Flatbush Pavilion theater and all spring everyone’s been talking about how we’re “living in the Matrix, man,” puffing on blunts of marijuana-filled cigars at house parties and discussing the subversive information laced throughout the film. People really get it: the society that we’ve been led to believe matters only serves the agenda of those who prop it up as the standard. Butch feels that everyone is on the verge of pulling the rubber pipe out the back of his head and redefining the social order. Society is in for an interesting turn; there’s no way The Matrix can be this popular and millions of moviegoers not understand what it’s really saying, he feels.

On top of this, every single day Butch sees someone on the A train to Manhattan with some sort of spiritual personal improvement book. If not Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet then Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. If not James Redfield’s The Celestine Prophecy then Dennis Kimbro’s Think and Grow Rich. He reads a few of them himself: Conversations With God, The Alchemist, The Four Agreements, The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success, Heal Thyself, Tapping the Power Within. Deepak Chopra becomes more of an omnipresent talking head on Butch’s TV set. Oprah redefines the mission of her talk show and urges her viewers to “be your best self,” “The Oprah Winfrey Show” exposing even exurban housewives to spiritualists like Yoruba minister Iyanla Vanzant on a regular basis. Things are coming together, Butch thinks. The sixties flirted with revolution; the nineties threaten the even greater prospect of evolution.

And as certain things come together, others fall apart—like the recording industry. Butch hasn’t bought a CD in quite a while. All the music he wants is available on Napster and he’s already laid down a few hundred dollars for a portable MP3 player. After decades of nefarious activities—contractually cheating musicians out of profits; overcharging the public for compact discs; paying artists less than fifteen percent of their music’s earnings and owning their master recordings forever and ever—record companies are feeling the big payback, revenge. To Butch, record companies seem like the first crumbling institution in a wave of falling multinational corporate entities to follow.

In the Brooklyn arts community surrounding him, unsigned independent bands all take encouragement from the digital revolution, burning their own CDs, setting up their own websites, selling their own music. Screw the industry. In the new age everyone can have his own record label, be her own CEO. One’s artistic worth won’t be measured or rejected by a corporation. On the verge of the twenty-first century Butch saw people self-actualizing, believing in themselves without looking for outside approval. How liberating.

To top things off the death of immediate hiphop icons Tupac Shakur and the Notorious BIG has made the power of intention common knowledge to the pop community. At first only a few made the crass observation that Biggie Smalls named his albums Ready to Die and Life After Death and was then killed; that Tupac rhymed incessantly about death and dying young and was murdered at twenty-five. The moral slowly spilling over into the mass consciousness? We get what we ask for, all of us. This was the beginning, Butch thought, of folks being more careful of what they put out into the universe, consciously exercising universal laws of cause and effect more carefully. It’s the biggest legacy the senseless deaths of the young and talented MCs could have left their generation.

Butch was all ready for the 2000s, bring ’em on. The Y2K computer scare came and went, tail between its legs. The election of George W. Bush didn’t bode well. But at the time it seemed at least to bring into question the notion of the Electoral College system, another antiquated structure ripe for rehauling and replacement for the new age.

And then September 11 came.

In 2001 the first foreign attack on US soil ushered in a period of disillusionment as considerable as that of the early seventies, at least for Butch and his peers. The idealism that typified his Brooklyn boho scene gradually dissolved. People moved. They had babies, took nine-to-fives to support families. Beset by the borough’s backbiting, Erykah Badu re-relocated back to Dallas with her and André 3000’s baby boy, Seven. Radio and listeners alike fell in love with Jill Scott’s debut; less preachy, less pretentious. Folks got lax with their meditation, started backsliding on their vegetarian diets, dismantling their altars. Cut their dredlocks, some of them. The Matrix sequels came out. They sucked. The government shut down Napster and the record industry appropriated the whole digital download movement: the iPod came out, and it didn’t suck. By and large the new age that Butch highly anticipated was a letdown, a non-event. Looking back, his lofty expectations started to appear softheaded as the years passed.

When someone eventually crafts a soundtrack for the disillusionment Butch’s generation feels for the thwarted promises of the Aquarian age—any day now, by my watch—it’ll without a doubt share a kindred spirit with There’s a Riot Goin’ On.

2

Postmillennial agita is a yet-undiagnosed social affliction. More documented by far is the sense of disappointment faced by the baby boomers at the end of the sixties. My childhood coincided with the birth of hiphop (in the Bronx, no less) and so all my knowledge concerning the spirit of those times is secondhand, but like even the most casual student of American history I still know it like the back of my (second) hand.

On my first birthday, December 18, 1971, There’s a Riot Goin’ On reached the top of the Billboard pop chart and its first single “Family Affair” had already been the number one pop single in the country for two weeks. In between the release of Sly and the Family Stone’s 1967 debut album A Whole New Thing and my turning a year old, both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated; Meredith Hunter was murdered at the Rolling Stones’ Altamont show; Vietnam War casualties were steadily escalating by the thousands; the US National Guard killed four students during a war demonstration at Kent State University; Charles Manson was sentenced to life imprisonment for the death of actress Sharon Tate and seven others; and seventeen-year-old Black Panther Bobby Hutton was killed by Oakland police in a shootout with the Panthers. Somewhere in there, spring 1969, the 5th Dimension’s “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures)” ruled the Billboard number one spot for six weeks—how discouraged the hippies must’ve been by the time I turned one.

This is a story often told: “the death of the sixties.” It usually begins by talking about how the decade didn’t precisely extend between 1960 and 1970 per se, but instead, for instance, between the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and the Rolling Stones’ free concert at Altamont Raceway, or the mainstreaming of the Pill and the government corruption of Watergate. I hate to add to the heap of cultural mythology surrounding this done-to-death decade from said angle but there’s almost no other “in” to begin explaining the downward spiral of Sly Stone, which is essential to understanding the genesis of There’s a Riot Goin’ On.

In Greil Marcus’s excellent essay on Riot, “The Myth of Staggerlee,” he characterizes Sly Stone as a believer whose faith was shattered. This tells the tale in a nutshell. “Don’t hate the black, don’t hate the white. If you get bitten just hate the bite,” he advised America (reciting lyrics from Dance to the Music’s “Are You Ready”) onstage at the “Sullivan Show” in December ’68. You can make it if you try, different strokes for different folks, and you don’t have to die before you live are just a few of the optimist messages spread in songs by Sly and the Family Stone during the heady days of the Summer of Love and Woodstock, where the septet performed before a countercultural audience 500,000 strong. But by the release of the stylishly mournful Riot, the man who once sang of hot fun in the summertime warned, “Watch out ’cause the summer gets cold when today gets too old.” Immensely bleak, moody, seductively despairing, and funky, Riot laid a sonic backdrop for the nationwide cultural and political disintegration of sixties fallout, as well as the personal dissolution of disillusioned idealist Sly Stone.

3

Critics always say Sly Stone was ahead of his time. I’ll go one better and prove it to you. Back in October 1969, Ben Fong-Torres interviewed him backstage at ABC’s short-lived “Music Scene.” (Sly and the Family Stone were awarded the cover of the three-year-old Rolling Stone in March 1970.1) The group’s maestro had this to say:

The record company wants another LP by February. Well, we could do some good songs, but that would be just another LP. Now you expect a group to come out with another LP and another. There’s got to be more to it. But what else can you do? The only thing that sounds interesting is something that ties in with a play that finishes what an LP starts to say, and the LP will be important on account of the play.

That’s a pretty spot-on synopsis of the concept behind Prince’s Purple Rain phenomenon fifteen years before the fact, wouldn’t you say? Or, you know, Mariah Carey’s Glitter…take your pick.

4

Sly Stone was born a simple Sylvester Stewart; it was his mother with the rather unique government name. Alpha “Big Mama” Stewart (she even has a sister named Omega) gave birth to Sylvester, the second of five children, on March 15, 1941, down in Denton, Texas. The Stewarts relocated to Vallejo, California, by the time Syl turned two. The Stewart Four formed from older sister Loretta, Freddie, Rose, and Sylvester when he was four years old, singing gospel. The deeply religious Big Mama and “Big Daddy” K. C. Stewart worshipped at the All Nations Church of God in Christ since the Stewart Four were in diapers—the couple met as teenagers at a church gathering. The children were so musically inclined they cut a gospel single—“On the Battlefield for My Lord” backed with “Walking in Jesus’ Name,” recorded on old-school chunky 78s—as early as 1952, at the behest of a preacher in Bakersfield. Syl sang lead. He was eleven.

As a teenager young Afrika Bambaataa famously carried out warlord duties for the Black Spades clique in the South Bronx. When he was a teen Syl—now officially going by “Sly”—ran with the Cherrybusters, a crew in the Vallejo area outfitted with identical orange jackets. But the Cherrybusters did a lot less damage than the Black Spades—zero, in fact. More a club than a gang, the Cherrybusters was more about looking cool than defending turf or warring on drug dealers preying on the neighborhood à la the Black Spades. Rock magazines sometimes cited Sly Stone as a back-in-the-day gang leader, and it’s impossible to say whether writers were getting carried away with their own imaginations re black stereotypes or if Sly sold himself that way. All told, his crew was more notorious for busting cherries than busting heads, and young Sly was hardly the leader—he was down mainly because of his ’53 Chevy, “Booty Green.”

Hiphop godfather Bambaataa has always cited Sly Stone as his major influence, which makes perfect sense. Both are gang members turned DJs turned music genre pioneers in their own right. (Bambaataa and Kool DJ Here are to hiphop what Sly Stone and James Brown are to funk. And maybe Grandmaster Flash equals George Clinton.)

At twenty-two, Sly Stewart scored a gig as A&R man and house producer for the fledgling Autumn Records, pretty much the same position that launched the career of Sean “Diddy” Combs at Uptown Records around the same age thirty years later. His position at Autumn was on the strength of a brief stint in the Viscaynes,2 a doo-wop sextet that prefigured the Family Stone in its male/female, multicultural membership. (Singer Frank Arelano was Filipino, the only member of color besides Sly himself.) He’d known them all since junior high school, singing with them since his high school days rolling with the Cherrybusters.

In 1961 the Viscaynes ended up releasing both “Yellow Moon” and “Stop What You’re Doing.” The same year Sly released his very first solo singles under the pseudonym Danny “Sly” Stewart: “A Long Time Alone” with the B-side “I’m Just a Fool”; “Are You My Girlfriend” b/w “You’ve Forgotten Me.” But “Yellow Moon” was the platter that mattered, getting enough local radio play to interest Autumn Records’ cofounder Tom Donahue in putting Sly on. (Donahue went by “Big Daddy” in his DJ days at KYA-AM—just like Sly’s daddy, interestingly enough.) Donahue and partner Bobby Mitchell put on showcases of local talent at a San Francisco venue called the Cow Palace. They hired Sly as the bandleader for these shows and soon he had a job at Autumn.

Behind the boards of a three-track recorder Sly produced a handful of near-middling acts in ’64: the Beau Brummels, Gloria Scott & the Tonettes, the Spearmints. Bobby Freeman scored a hit that year with Sly’s “C’mon and Swim.” He continued sharpening his production skills the next year cutting the Mojo Men, the Vejtables, Bertha Tillman, the Tikis, Emile O’Connor, and Chosen Few. Autumn released Sly Stewart singles as well—“I Just Learned How to Swim,” “Scat Swim,” “Buttermilk,” “Temptation Walk”—but they made no noise.

After an open audition for Autumn Records at Mother’s, a nightclub also owned by Donahue, the label almost signed the Great Society. Grace Slick, one the original rock grrrls of the San Francisco acid-rock scene, would soon leave the group and take the Summer of Love staple “Somebody to Love” with her to Jefferson Airplane. Before the track became a top ten hit, Slick and the Great Society spent many hours in the studio with Sly laying down songs they performed at Mother’s as a sort of audition demo for Donahue. Recording around fifty takes of “Somebody to Love” killed the vibe between Autumn and the Great Society, but not long after America had a new anthem for the times via Jefferson Airplane.

Unlike the self-taught Diddy’s sampling production for his early hits by the likes of Mary J. Blige, Sly had already attended three semesters at Vallejo Junior College and received music theory tutelage from teacher David Froelich. Sly continued to thank Froelich for his instruction in liner notes throughout his career. At around the same time Sly first came across Orchestration by Walter Piston, a book he’d later refer to constantly according to Epic Records A&R man Stephen Paley.

Then there was the deejaying. Tom Donahue sold Autumn Records to Warner Bros. in ’64; Sly spent three months at the Chris Borden School of Modern Broadcasting and landed another music biz job as the Monday through Saturday nightshift DJ at the San Fran soul station KSOL in October. Here he brandished his colorblind musical taste till June of ’67, mixing Bob Dylan with the Marvelettes, or R&B’s “I Only Have Eyes for You” alongside rock’s “Tomorrow Never Knows.” (Afrika Bambaataa’s deejaying style has always been equally eclectic.) At eleven o’clock Sly featured his nightly integration record, a track by a rock act he loved. He played live piano during his signoff, singing Jesse Belvin’s “Goodnight My Love” as a personal signature. This is where Sly Stone was really born into the world, his persona and his aesthetic.

“When I was a disc jockey,” Sly told writer Al Aronowitz, “I ha...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Sly Talk

- The Believer Whose Faith Was Shattered

- What’s Goin’ On?

- 0:00

- The Lyrics

- Copyright